Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) addresses problems of interaction design: delivering novel designs, evaluating existing designs, and understanding user needs for future designs. Qualitative methods have an essential role to play in this enterprise, particularly in understanding user needs and behaviours and evaluating situated use of technology. There are, however, a huge number of qualitative methods, often minor variants of each other, and it can seem difficult to choose (or design) an appropriate method for a particular study. The focus of this chapter is on semi-structured qualitative studies, which occupy a space between ethnography and surveys, typically involving observations, interviews and similar methods for data gathering, and methods for analysis based on systematic coding of data. This chapter is pragmatic, focusing on principles for designing, conducting and reporting on a qualitative study and conversely, as a reader, assessing a study. The starting premise is that all studies have a purpose, and that methods need to address the purpose, taking into account practical considerations. The chapter closes with a checklist of questions to consider when designing and reporting studies.

43.1 Introduction

HCI has a focus (the design of interactive systems), but exploits methods from various disciplines. One growing trend is the application of qualitative methods to better understand the use of technology in context. While such methods are well established within the social sciences, their use in HCI is less mature, and there is still controversy and uncertainty about when and how to apply such methods, and how to report the findings (e.g. Crabtree et al., 2009).

This chapter takes a high-level view on how to design, conduct and report semi-structured qualitative studies (SSQSs). Its perspective is complementary to most existing resources (e.g. Adams et al., 2008; Charmaz, 2006; Lazar et al., 2010; Smith, 2008; onlineqda.hud.ac.uk), which focus on method and principles rather than basic practicalities. Because ‘method’ is not a particularly trendy topic in HCI, I draw on the methods literature from psychology and the social sciences as well as HCI. Rather than starting with a particular method and how to apply it, I start from the purpose of a study and the practical resources and constraints within which the study must be conducted.

I do not subscribe to the view that there is a single right way to conduct any study: that there is a minimum or maximum number of participants; that there is only one way to gather or analyse data; or that validation has to be achieved in a particular way. As Willig (Willig, 2008, p.22) notes, “Strictly speaking, there are no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ methods. Rather, methods of data collection and analysis can be more or less appropriate to our research question.” Woolrych et al. (2011) draw an analogy with ingredients and recipes: the art of conducting an effective study is in pulling together appropriate ingredients to construct a recipe that is right for the occasion – i.e., addresses the purpose of the study while working with available resources.

The aim of this chapter is to present an overview of how to design, conduct and report on SSQSs. The chapter reviews methodological literature from HCI and the social and life sciences, and also draws on lessons learnt through the design, conduct and reporting of various SSQSs. The chapter does not present any method in detail, but presents a way of thinking about SSQSs in order to study users’ needs and situated practices with interactive technologies.

The basic premise is that, starting with the purpose of a study, the challenge is to work with the available resources to complete the best possible study, and to report it in such a way that its strengths and limitations can be inspected, so that others can build on it appropriately. The chapter summarises and provides pointers to literature that can help in research, and at the end a checklist of questions to consider when designing, conducting, reporting on, and reviewing SSQSs. The aim is to deliver a reference text for HCI researchers planning semi-structured qualitative studies.

43.1.1 What is an SSQS?

The term ‘semi-structured qualitative study’ (SSQS) is used here to refer to qualitative approaches, typically involving interviews and observations, that have some explicit structure to them, in terms of theory or method, but are not completely structured. Such studies typically involve systematic, iterative coding of verbal data, often supplemented by data in other modalities.

Some such methods are positivist, assuming an independent reality that can be investigated and agreed upon by multiple researchers; others are constructivist, or interpretivist, assuming that reality is not ‘out there’, but is constructed through the interpretations of researchers, study participants, and even readers. In the former case, it is important that agreement between researchers can be achieved. In the latter case, it is important that others are able to inspect the methods and interpretations so that they can comprehend the journey from an initial question to a conclusion, assess its validity and generalizability, and build on the research in an informed way.

In this chapter, we focus on SSQSs addressing exploratory, open-ended questions, rather than qualitative data that is incorporated into hypothetico-deductive research designs. Kidder and Fine (Kidder and Fine 1987, p.59) define the former as “big Q” and the latter as “small q”, where “big Q” refers to “unstructured research, inductive work, hypothesis generation, and the development of ‘grounded theory’”. Their big Q encompasses ethnography (Section 1.4) as well as the SSQSs that are the focus here; the important point is that SSQSs focus on addressing questions rather than testing hypotheses: they are concerned with developing understanding in an exploratory way.

One challenge with qualitative research methods in HCI is that there are many possible variants of them and few names to describe them. If every one were to be classed as a ‘method’ there would be an infinite number of methods. However, starting with named methods leaves many holes in the space of possible approaches to data gathering and analysis. There are many potential methods that have no name and appear in no textbooks, and yet are potentially valid and valuable for addressing HCI problems.

This contrasts with quantitative research. Within quantitative research traditions – exemplified by, but not limited to, controlled experiments – there are well-established ways of describing the research method, such that a suitably knowledgeable reader can assess the validity of the claims being made with reasonable certainty, for example, hypothesis, independent variable, dependent variable, power of test, choice of statistical test, number of participants.

The same is not true for SSQSs, where there is no hypothesis – though usually there is a question, or research problem – where the themes that emerge from the data may be very different from what the researcher expected, and where the individual personalities of participants and their situations can have a huge influence over the progress of the study and the findings.

Because of the shortage of names for qualitative research methods, there is a temptation to call a study an ‘ethnography’ or a ‘Grounded Theory’ (both described below: Section 1.4 and Section 1.5) whether or not they have the hallmarks of those methods as presented in the literature. Data gathering for SSQSs typically involves the use of a semi-structured interview script or a partial plan for what to focus attention on in an observational study.

There is also some structure to the process of analysis, including systematic coding of the data, but usually not a rigid structure that constrains interpretation, as discussed in Section 7. SSQSs are less structured than, for example, a survey, which would typically allow people to select from a range of pre-determined possible answers or to enter free-form text into a size-limited text box. Conversely, they are more structured than ethnography – at least when that term is used in its classical sense; see Section 1.4.

43.1.2 A starting point: problems or opportunities

Most methods texts (e.g. Cairns and Cox, 2008; Lazar et al., 2010; Smith, 2008; Willig, 2008) start with methods and what they are good for, rather than starting with problems and how to select and adapt research methods to address those problems. Willig (Willig, 2008, p.12) even structures her text around questions about each of the approaches she presents:

“What kind of knowledge does the methodology aim to produce? … What kinds of assumptions does the methodology make about the world? … How does the methodology conceptualise the role of the researcher in the research process?”

If applying a particular named method, it is important to understand it in these terms to be able to make an informed choice between methods. However, by starting at the other end – the purpose of the study and what resources are available – it should be possible to put together a suitable plan for conducting a SSQS that addresses the purpose, makes relevant assumptions about the world, and defines a suitable role for the researcher.

Some researchers become experts in particular methods and then seek out problems that are amenable to that method; for example, drawing from the social sciences rather than HCI, Giorgi and Giorgi (Giorgi and Giorgi, 2008) report seeking out research problems that are amenable to their phenomenology approach. On the one hand, this enables researchers to gain expertise and authority in relation to particular methods; on the other, this risks seeing all problems one way: “To the man who only has a hammer, everything he encounters begins to look like a nail”, to quote Abraham Maslow.

HCI is generally problem-focused, delivering technological solutions to identified user needs. Within this, there are two obvious roles for SSQSs: understanding current needs and practices, and evaluating the effects of new technologies in practice. The typical interest is in how to understand the ‘real world’ in terms that are useful for interaction design. This can often demand a ‘bricolage’ approach to research, adopting and adapting methods to fit the constraints of a particular problem situation. On the one hand this makes it possible to address the most pressing problems or questions; on the other, the researcher is continually having to learn new skills, and can always feel like an amateur.

In the next section, I present a brief overview of relevant background work to set the context, focusing on qualitative methods and their application in HCI. Subsequent sections cover an approach to planning SSQSs based on the PRET A Rapporter framework (Blandford et al., 2008) and discuss specific issues including the role of theory in SSQSs, assessing and ensuring quality in studies, and various roles the researcher can play in studies. This chapter closes with a checklist of issues to consider in planning, conducting and reporting on SSQSs.

43.1.3 A brief overview of qualitative methods

There has been a growing interest in the application of qualitative methods in HCI. Suchman’s (Suchman, 1987) study of situated action was an early landmark in recognising the importance of studying interactions in their natural context, and how such studies could complement the findings of laboratory studies, whether controlled or employing richer but less structured techniques such as think aloud.

Sanderson and Fisher (Sanderson and Fisher, 1994) brought together a collection of papers presenting complementary approaches to the analysis of sequential data (e.g., sequences of events), based on a workshop at CHI 1992. Their focus was on data where sequential integrity had been preserved, and where sense was made of the data through relevant techniques such as task analysis, video analysis, or conversation analysis. The interest in this collection of papers is not in the detail, but in the recognition that semi-structured qualitative studies had an established place in HCI at a time when cognitive and experimental methods held sway.

Since then, a range of methods have been developed for studying people’s situated use and experiences of technology, based around ethnography, diaries, interviews, and similar forms of verbal and observable qualitative data (e.g. Lindtner et al. 2011; Mackay 1999; Odom et al. 2010; Skeels & Grudin 2009).

Some researchers have taken a strong position on the appropriateness or otherwise of particular methods. A couple of widely documented disagreements are briefly discussed below. This chapter avoids engaging in such ‘methods wars’. Instead, the position, like that of Willig (2008) and Woolrych et al. (2011), is that there is no single correct ‘method’, or right way to apply a method: the textbook methods lay out a space of possible ways to conduct a study, and the details of any particular study need to be designed in a way that maximises the value, given the constraints and resources available. Before expanding on that theme, we briefly review ethnography – as applied in HCI – and Grounded Theory, as a descriptor that is widely used to describe exploratory qualitative studies.

43.1.4 Ethnography: the all-encompassing field method?

Miles and Huberman (Miles and Huberman 1994, p.1) suggest, “The terms ethnography, field methods, qualitative inquiry, participant observation, … have become practically synonymous”. Some researchers in HCI seem to treat these terms as synonymous too, whereas others have a particular view of what constitutes ‘ethnography’. For the purposes of this chapter, an ethnography involves observation of technology-based work leading to rich descriptions of that work, without either the observation or the subsequent description being constrained by any particular structuring constructs. This is consistent with the view of Anderson (1994), and Randall and Rouncefield (2013).

Crabtree et al. (2009) present an overview – albeit couched in somewhat confrontational terms – of different approaches to ethnography in HCI. Button and Sharrock (2009) argue, on the basis of their own experience, that the study of work should involve “ethnomethodologically informed ethnography”, although they do not define this succinctly. Crabtree et al. (Crabtree et al. 2000 , p.666) define it as study in which “members’ reasoning and methods for accomplishing situations becomes the topic of enquiry”.

Button and Sharrock (2009) present five maxims for conducting ethnomethodological studies of work: keep close to the work; examine the correspondence between work and the scheme of work; look for troubles great and small; take the lead from those who know the work; and identify where the work is done. They emphasise the importance of paying attention, not jumping to conclusions, valuing observation over verbal report, and keeping comprehensive notes. However, their guidance does not extend to any form of data analysis. In common with others (e.g. Heath & Luff, 1991; Von Lehn & Heath, 2005), the moves that the researcher makes between observation in the situation of interest and the reporting of findings remain undocumented, and hence unavailable to the interested or critical reader.

According to Randall and Rouncefield (2013), ethnography is “a qualitative orientation to research that emphasises the detailed observation of people in naturally occurring settings”. They assert that ethnography is not a method at all, but that data gathering “will be dictated not by strategic methodological considerations, but by the flow of activity within the social setting”.

Anderson (1994) emphasises the role of the ethnographer as someone with an interpretive eye delivering an account of patterns observed, arguing that not all fieldwork is ethnography and that not everyone can be an ethnographer. In SSQSs, our focus is on methods where data gathering and analysis are more structured and open to scrutiny than these flavours of ethnography.

43.1.5 Grounded Theory: the SQSS method of choice?

I am introducing Grounded Theory (GT) early in this chapter because the term is widely used as a label for any method that involves systematic coding of data, regardless of the details of the study design, and because it is probably the most widely applied SSQS method in HCI.

GT is not a theory, but an approach to theory development – grounded in data – that has emerged from the social sciences. There are several accounts of GT and how to apply it, including Glaser and Strauss (2009), Corbin and Strauss (2008), Charmaz (2006), Adams et al. (2008), and Lazar et al. (2010).

Historically, there have been disputes on the details of how to conduct a GT: the disagreement between Glaser and Strauss, following their early joint work on Grounded Theory (Glaser and Strauss, 2009), has been well documented (e.g. Charmaz, 2008; Furniss et al., 2011a, Willig, 2008). Charmaz (2006) presents an overview of the evolution of different strains of GT prior to that date.

Grbich (2013) identifies three main versions of GT, which she refers to as Straussian, involving a detailed three-stage coding process; Glaserian, involving less coding but more shifting between levels of analysis to relate the details to the big picture; and Charmaz’s, which has a stronger constructivist emphasis.

Charmaz (Charmaz 2008, p.83) summarises the distinguishing characteristics of GT methods as being:

Simultaneous involvement in data collection and analysis;

Developing analytic codes and categories “bottom up” from the data, rather than from preconceived hypotheses;

Constructing mid-range theories of behaviour and processes;

Creating analytic notes, or memos, to explain categories;

Constantly comparing data with data, data with concept, and concept with concept;

Theoretical sampling – that is, recruiting participants to help with theory construction by checking and refining conceptual categories, not for representativeness of a given population;

Delaying literature review until after forming the analysis.

There is widespread agreement amongst those who describe how to apply GT that it should include interleaving between data gathering and analysis, that theoretical sampling should be employed, and that theory should be constructed from data through a process of constant comparative analysis. These characteristics define a region in the space of possible SSQSs, and highlight some of the dimensions on which qualitative studies can vary. I take the position that the term ‘Grounded Theory’ should be reserved for methods that have these characteristics, but even then it is not sufficient to describe the method simply as a Grounded Theory without also presenting details on what was actually done in data gathering and analysis.

As noted above, much qualitative research in HCI is presented as being Grounded Theory, or a variant on GT. For example, Wong and Blandford (2002) present Emergent Themes Analysis as being “based on Grounded Theory but tailored to take advantage of the exploratory and efficient data collection features of the CDM” – where CDM is the Critical Decision Method (Klein et al., 1989) as outlined in section 6.4.

McKechnie et al. (2012) describe their analysis of documents as a Grounded Theory, and also discuss the use of inter-rater reliability – both activities that are inconsistent with the distinguishing characteristics of GT methods if those are taken to include interleaving of data gathering and analysis and a constructivist stance. GT has been used as a ‘bumper sticker’ to describe a wide range of qualitative analysis approaches, many of which diverge significantly from GT as presented by the originators of that technique and their intellectual descendants.

Furniss et al. (2011a) present a reflective account of the experience of applying GT within a three-year project, focusing particularly on pragmatic ‘lessons learnt’. These include practical issues such as managing time and the challenges of recruiting participants, and also theoretical issues such as reflecting on the role of existing theory – and the background of the analyst – in informing the analysis.

Being fully aware of relevant existing theory can pose a challenge to the researcher, particularly if the advice to delay literature review is heeded. If the researcher has limited awareness of relevant prior research in the particular domain, it can mean ‘rediscovery’ of theories or principles that are, in fact, already widely recognized, leading to the further question, “So what is new?” We return to the challenge of how to relate findings to pre-existing theory, or literature that emerges as being important through the analysis, in section 9.1.

43.2 Planning and conducting a study: PRET A Rapporter

Research generally has some kind of objective (or purpose) and some structure. A defining characteristic of SSQSs is that they have shape… but not too much: that there is some structure to guide the researcher in how to organise a study, what data to gather, how to analyse it, etc., but that that structure is not immutable, and can adapt to circumstances, evolving as needed to meet the overall goals of the study. The plan should be clear, but is likely to evolve over the course of a study, as understanding and circumstances change.

Thomas Green used to remind PhD students to “look after your GOST”, where a GOST is a Grand Overall Scheme of Things – his point being that it is all too easy to let the aims of a research project and the fine details get out of synch, and that they need to be regularly reviewed and brought back into alignment.

We structure the core of this chapter in terms of the PRET A Rapporter (PRETAR) framework (Blandford et al., 2008a), a basic structure for designing, conducting and reporting studies. Before presenting this structure, though, it is important to emphasise the basic interconnectedness of all things: in the UK a few years ago there was a billboard advertisement, “You are not stuck in traffic. You are traffic” (Figure 1).

It is impossible to separate the components of a study and treat them completely independently – although they have some degree of independence. The style of data gathering influences what analysis can be performed; the relationship established with early participants may influence the recruitment of later participants; ethical considerations may influence what kinds of data can be gathered, etc. We return to this topic of interdependencies later; first, for simplicity of exposition, we present key considerations in planning a study using the PRETAR framework.

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Ann Blandford. Copyright terms and licence: CC-Att-ND-3 (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported).

Figure 43.1: An example of interconnectedness

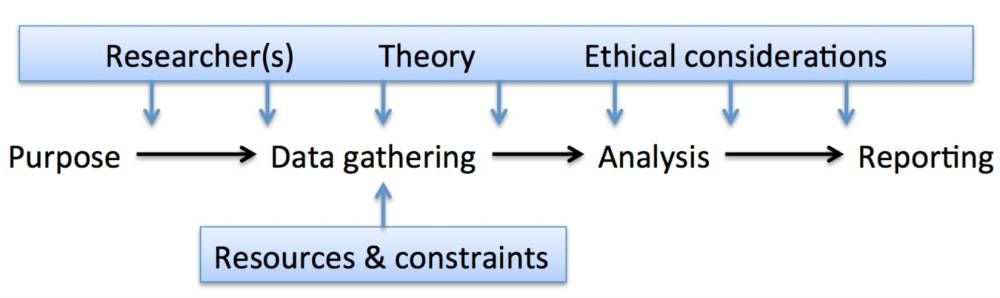

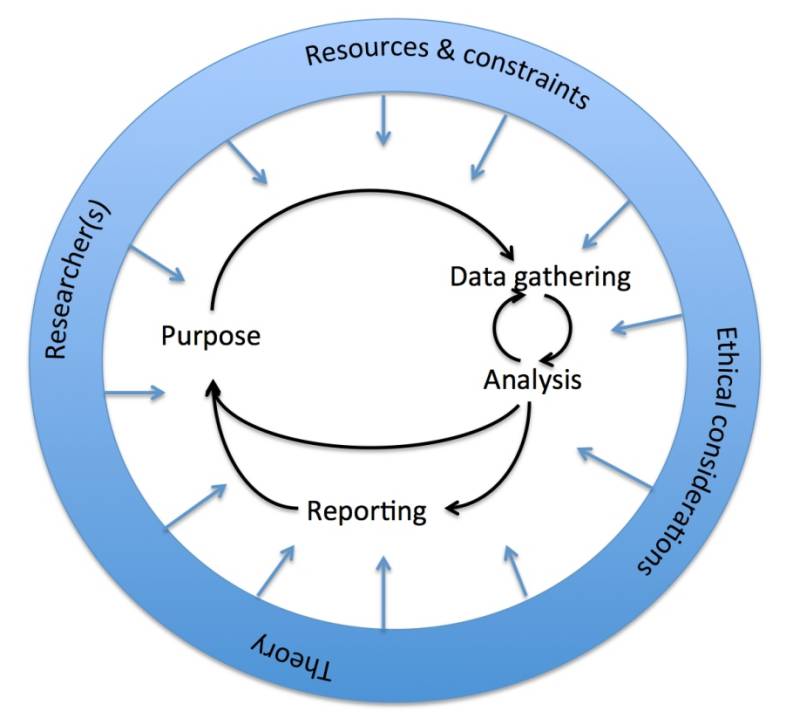

The PRETAR framework draws its inspiration from the DECIDE framework proposed by Rogers et al. (2011), but has a greater emphasis on the later – analysis and reporting – stages that are essential to any SSQS:

Purpose: every study has a purpose, which may be more or less precisely defined; methods should be selected to address the purpose of the study. The purpose of a study may change as understanding develops, but few people are able to conduct an effective study without some idea of why they are doing it.

Resources and constraints: every study has to be conducted with the available resources, also taking account of existing constraints that may limit what is possible.

Ethical considerations often shape what is possible, particularly in terms of how data can be gathered and results reported.

Techniques for data gathering need to be determined (working with the available resources to address the purpose of the study).

Analysis techniques need to be appropriate to the data and the purpose of the study.

Reporting needs to address the purpose of the study, and communicate it effectively to the intended audiences. In some cases, this will include an account of how and why the purpose has evolved, as well as the methods, results, etc.

Some authors have focused attention on one of these steps; for example, Kvale and Brinkmann (2009) focus primarily on data gathering while Miles and Huberman (1994), Grbich (2013) and Braun and Clarke (2006) focus on analysis, and Morse (1997) and Wolcott (2009) on reporting and other aspects of closing off a research project. However, these steps are not independent, and are typically interleaved in SSQSs. What matters is that they remain coherent – that there is a clear GOST. For example, the researcher’s view of the purpose of a study may evolve as their understanding matures through data gathering and analysis.

As noted above (section 1.5), GT is based on tight coupling between data gathering and analysis; other analysis techniques assume no such coupling. These steps provide a useful structure to organise our discussion on planning and conducting a study, but should not be regarded as strictly sequential or independent.

43.3 Purpose

Every study has a purpose. That purpose might be to better understand:

‘work’, broadly conceived, and how interactive technologies support or fail to support that work (e.g. Hartswood et al., 2003; Hughes et al., 1994);

people’s experiences with a particular kind of technology (e.g. Palen, 1999; Kindberg et al., 2005; Mentis et al., 2013);

how people exploit technologies to support cognition (e.g. Hutchins 1995);

how people make sense of information with and without particular technological support (e.g. Attfield and Blandford, 2011); or

many other aspects of the design and use of interactive technologies.

The recent ‘turn to the wild’ (Rogers, 2012), in which novel products are designed in situ, working directly with the intended users of those products, introduces yet more possible purposes for qualitative studies: to understand how a new product changes attitudes and behaviours, and how the design of the product might be adapted to better support people’s needs and aspirations.

Crabtree et al. (2009)argue that the purpose of an ethnographic study in HCI is to inform system design. They claim that ethnographic research to inform systems design has shifted from a study of work towards a study of culture, and that this shift is “harmful”. In creating an either/or stand-off, the authors pit the contrasting ethnographic focuses against each other, apparently disregarding the possibility that each has a place in informing design, and that different ethnographic studies of the same context can serve different purposes. The same is true of SSQSs: they can address many different questions that inform design – though whether ‘informing design’ should mean that there are explicitly stated ‘implications for design’ is a further question.

Crabtree et al. (2009) suggests that there is a widespread expectation that studies will always include “implications for design” as an explicit theme, and that this is expected in reporting even if that was not the purpose of the study. He argues that designers need a rich understanding of the situation for which they are designing, and that one of the important roles for ethnography is to expose and describe that cultural context for design, without necessarily making the explicit link to implications for design. This might be regarded as an argument for helping designers to put themselves in the user’s shoes when they are not designing for themselves, for example, designing specialist products to support work or other activities in which they are not experts themselves.

Obviously, not all studies should be qualitative, and certainly not all should be semi-structured. Yardley (Yardley 2000, p.220) differentiates between the typical purposes of qualitative and quantitative studies:

“Quantitative studies … ensure the ‘horizontal generalization’ of their findings across research settings … qualitative researchers aspire instead to … ‘vertical generalization’, i.e., an endeavour to link the particular to the abstract and to the work of others”.

In HCI, qualitative studies – whether structured, semi-structured or ethnographic – most typically focus on understanding technology use, or future technology needs, in situated settings, recognizing that laboratory studies are limited when it comes to investigating issues around real-world use.

In summary, there are many purposes for which SSQSs are well suited. There are others that demand other techniques, such as controlled laboratory studies or ethnography (in the sense discussed in section 1.4); what matters is that the study design suits the study purpose.

There are, of course, purposes that cannot, in practice, be addressed reliably, for legal, safety, privacy, ethical or similar reasons. For example, in safety-critical situations, the presence of researchers could be a distraction when conditions become demanding, so it may not be possible to study the details of interactions at times of greatest stress. It is not theoretically or practically possible to address every imaginable research question in HCI.

The centrality of purpose is emphasised by Wolcott (Wolcott 2009, p.34), who advocates “a candidate for the opening sentence for scholarly writing: ‘The purpose of this study is…’”. While the purpose should drive the study design, and might evolve in the light of early study findings, it may also have to be crafted to fit the available resources.

43.4 Resources and constraints

Every study has to be designed to work with the available resources. Where resources are limited by, for example, time or budgetary restraints, it is necessary to ‘cut your coat according to your cloth’ – i.e., to fit ambitions and hence purpose to what is possible with the available resources.

Resource considerations need to cover – at least – time, funding, equipment available for data collection and analysis, availability of places to conduct the study, availability of participants, and expertise. In many cases, it is also necessary to have advocacy and support from people with influence in the intended study settings. Of these resources, three that merit further discussion are advocacy, participants and expertise.

43.4.1 Advocacy

Sometimes, studies are devised and run in collaboration with ‘problem owners’ (e.g. Randell et al, 2013), but other studies are conceived by a research team outside a particular domain setting. In some cases, it is essential to get support from a domain specialist.

For example, in the work of the author and co-workers, with a shift in emphasis in healthcare from hospital to home, we are interested in how medical devices are taken up and used in the home, and how products that were originally developed for use by clinical staff in hospitals can be adapted to be suitable for home use. There are some products that are well established for home use, such as nebulisers, blood glucose monitors and dialysis machines, and others that are making the transition from hospital to home, such as patient-controlled analgesia and intravenous administration of chemotherapy.

We followed several lines of enquiry to identify clinicians who expressed an interest in patients’ experiences of intravenous therapies at home, but all eventually drew a blank. In contrast, we identified several nephrologists who were sufficiently interested in patients’ experience of home haemodialysis to introduce us to their patients. This has led to a productive study (e.g. Rajkomar et al., 2013).

In other cases, it may be important to obtain permission to conduct a study in a particular location; for example, Perera (2006)investigated under what circumstances people forgot their chip-and-pin cards in shops, and she needed to obtain permission from shop managers to conduct observational studies on their premises.

In another case, in work for a Masters project (O’Connor, 2011), support was needed from the nursing manager in the emergency department; as soon as she was contacted, it was clear that she was keen to support others in their education, and this was the main factor in her supporting the project, rather that its inherent interest. In yet other cases, there is no particular advocate or manager to involve; for example, studies of diabetes patients (e.g. O’Kane & Mentis, 2012) involved direct recruitment of participants without mediation from specialists.

There may be a hidden cost in negotiating support from advocates, but this often brings with it the benefits of close engagement with the study domain, introductions to potential participants, and longer-term impact through the engagement of stakeholders.

43.4.2 Participants: recruitment and sampling

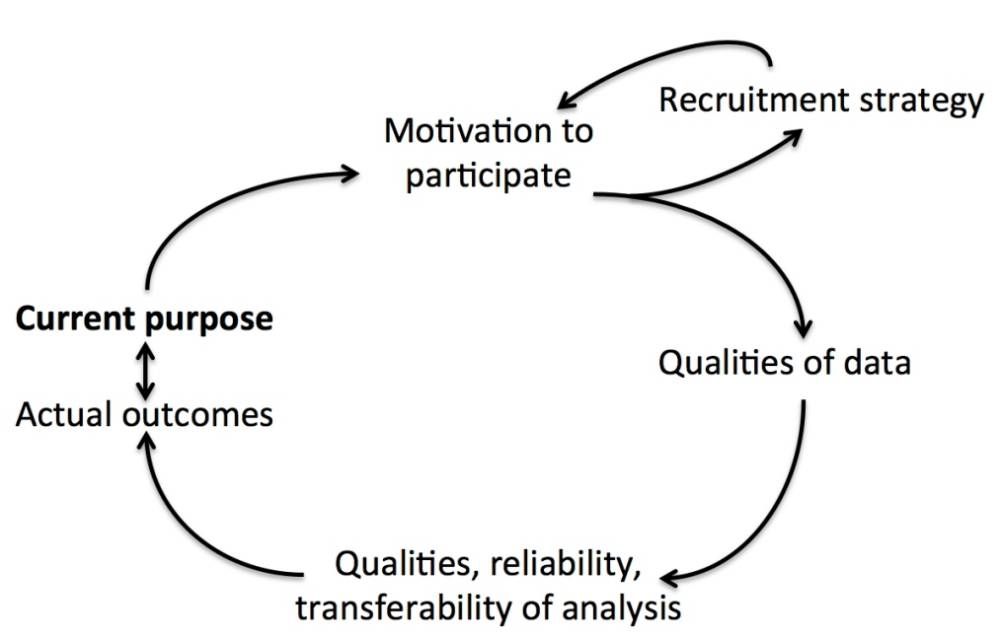

When recruiting participants for a study, with or without the advocacy of an intermediary, it is important to consider their motivations for participation. This is partly coupled with ethical considerations (Section 5), and partly with how to incentivise people to participate at all. People may agree or elect to participate in studies for many different reasons: maybe it is low-cost (in terms of time and effort), and people just want to be helpful.

This was probably the case in the studies of ambulance control carried out by Blandford & Wong (2004). The immediate benefits to participants, ambulance controllers, were relatively small, beyond the sense that someone else was interested in their work and valued their expertise. However, the costs of participation were also low – continue to do your job as normal, and talk about the work in slack periods when you would otherwise simply be waiting for the next call.

In other cases, participants may be inherently interested in the project – as in some of our work on serendipity (Makri & Blandford, 2012) – or perceive some personal benefit, for example, in reflecting on how you manage your time (Kamsin et al., 2012). Some people may participate for financial reward, or to return a favour. And of course, people’s motivations for participating may be mixed.

Where the topic is one that participants might be sensitive about, for example, intimate health issues, it can sometimes help to have pre-existing common ground between the researcher doing data gathering and the participant, such as being of the same sex or a similar age. Where multiple researchers are available, this might mean matching them well to participants; where there is a single researcher, it might mean reviewing the purpose of the study to be sure that data gathering is likely to be productive. In the section on ethics (Section 5), we discuss relationships with participants and how these relate to recruitment and motivations for participating.

The choice of approaches to recruitment depends on the purpose of the study and the kinds of participant needed. Possible approaches include:

Direct contact – e.g. approaching individuals in the workplace, with authorisation from local managers if needed, or approaching people in public spaces, with due regard for safety, informed consent, etc..

Mediated contact: an introduction by someone else, such as a line manager in the workplace, another ‘gatekeeper’ – for example, a teacher, or the organiser of a relevant ‘special interest’ group – or friends or other participants.

Advertising: on noticeboards in physical space, through targeted email lists, via online lists and social networks.

As social media and other technologies evolve, new approaches to recruiting study participants are emerging. What matters is that the approach to recruitment is effective in terms of recruiting both a suitable number of participants and appropriate participants for the aims of the study.

Two questions that come up frequently are how many participants should be included and how they should be sampled. The answer to both is ‘it depends’ – on the aims of the study, and what is possible with the available resources.

Although not common in HCI, it is possible to conduct a study with a single participant, as a rich case study. For example, Attfield et al. (2008) gathered observations, interview data and examples of artefacts produced from a single journalist as that journalist prepared an article from inception to publication. The aim of the study was to understand the phases of work, how information was transformed through that work, and how technology supported the work.

Such a case study provides a rich understanding of the interaction, but care has to be taken over generalizing: ideally, such a case will be compared with known features of comparable cases, in terms of both similarities and contrasts. In poorly understood areas, even a single rich case study can add to our overall understanding of the design, deployment and use of interactive technologies. But most studies involve many more participants than one.

Smith (Smith 2008, p.14) draws the distinction between idiographic and nomothetic research as follows:

“The nomothetic approach assumes that the behaviour of a particular person is the outcome of laws that apply to all, and the aim of science is to reveal these general laws. The idiographic approach would, in contrast, focus on the interplay of factors which may be quite specific to the individual.”

In other words, nomothetic research relies more on large samples and statistical techniques to establish generalizations, for example, through controlled experiments. SSQSs typically involve much smaller numbers of participants, occasionally as few as one, but more commonly 10-20, but gathers rich data with each. In this sense, SSQSs are idiographic, and care must be taken with generalizing beyond the study setting. This is a topic to which we return in Section 10.1.

GT researchers resist specifying numbers of participants required. Rather, they advocate continuing to gather data until the theoretical categories of the analysis are saturated. Charmaz (Charmaz 2006, p. 113) explains: “Categories are ‘saturated’ when gathering fresh data no longer sparks new theoretical insights, nor reveals new properties of your core theoretical categories”. In other words, you stop gathering data when it no longer advances the study. This presupposes an iterative approach to data gathering and analysis, which is the case for GT, but not for other styles of qualitative research where all data may be gathered before analysis commences.

In practice, there are often pragmatic factors that determine how many participants to involve in a study. One might be the time available: it can take a long time to recruit each participant, to arrange and conduct data gathering, and analyse the data. Another might be the availability of participants who satisfy the recruitment criteria, for example, performing a particular role in an organisation or having particular experience. A shorter study with fewer participants needs to be more focused in order to deliver insight, because otherwise it risks delivering shallow data from which it is almost impossible to derive valuable insight.

Thought must be given to how to sample participants. Sometimes, the criteria are quite broad , for example, people who enjoy playing video games, and it is possible to recruit through public advertising. Sometimes, they are focused, such as on people with a particular job role within an organisation.

For other studies, the aim might be to obtain a representative sample; for example, in a study of lawyers’ use of information resources (Makri et al., 2008), our aim was to involve lawyers across the range of seniority, from undergraduate students to senior partners in a law firm and professors in a university law department.

However, in qualitative research it is rare to aim for probability sampling, as one would for quantitative studies. Marshall (1996) discusses three different approaches to sampling for qualitative research: convenience, judgement (also called purposeful), and theoretical.

Convenience sampling involves working with the most accessible participants, and is therefore the easiest approach.

Judgment sampling, in which the “researcher actively selects the most productive sample to answer the research question” (p. 523), is the most commonly used in HCI.

Theoretical sampling is advocated within GT, and involves recruiting participants who are most likely to help build the theory that is emerging through data gathering and analysis.

Miles and Huberman (Miles and Huberman 1994, p.28) list no fewer than 16 different approaches to sampling, such as maximum variation, extreme or deviant case, typical case, and stratified purposeful, each with a particular value in terms of data gathering and analysis.

An approach to sampling that can be particularly useful for accessing hard-to-reach populations, for example, people using a particular specialist device, is snowball sampling, where each participant introduces the researcher to further participants who satisfy their inclusion criteria.

Atkinson and Flint (2001) highlight some of the limitations of this approach, in terms of participant diversity and consequent generalizability of findings. Slightly tongue-in-cheek, they also describe “scrounging sampling”: the increasingly desperate acquisition of participants to make up numbers almost regardless of suitability. While few authors are likely to admit to applying scrounging sampling as a strategy for recruitment, it is important to explain clearly how and why participants have been recruited and the likely consequences of the recruitment strategy on findings.

The same issue arises when there might be barriers to recruitment. Buckley et al. (2007) highlight the dangers of ‘consent bias’, whereby those with more positive outcomes are more likely to agree to participate in a study. Although most of the literature on consent bias relates to healthcare studies, there are similar risks in HCI studies, particularly where the technology under investigation is related to a sensitive personal issue, such as behaviour change technologies. Atkinson and Flint (2001) also highlight the risks of ‘gatekeeper bias’, where those in authority – for example, clinicians or teachers – filter out potential participants whom they consider less suitable.

In summary, when planning a study, it is important to consider questions of recruitment and relationship management:

Who the appropriate participants are and how they should be recruited;

Where and when to work with them in data gathering; and

How (or whether) to engage with them more broadly from the start to the end of a study.

Throughout recruitment, study design and data analysis, it is important to remain aware of participants’ motivations for participating, and their expectations of the outcome, whether this is, for example, the expectation of novel interaction designs, or simply to gain the experience of participating. These factors are addressed further in Section 5.

When dealing with sensitive topics where people may have reasons for sharing or withholding certain information, or for behaving in particular ways, it is also important to be aware of motivations and their possible effects on the data that is gathered. Such considerations imply the need (a) to review data gathering techniques to maximise the likelihood of gathering valid data (see Section 6) and (b) to reflect on the data quality and implications for the findings (see Section 10.1).

43.4.3 Expertise of the research team

There are at least two aspects to expertise: that in qualitative research and that in the study domain.

There is no shortcut to acquiring expertise in qualitative research. Courses, textbooks and research papers provide essential foundations, and different resources resonate with – and are therefore most useful to – different people. Corbin and Strauss (Corbin and Strauss 2008, p.27) emphasise the importance of planning and practice:

“Persons sometimes think that they can go out into the field and conduct interviews or observations with no training or preparation. Often these persons are disappointed when their participants are less than informative and the data are sparse, at best.”

Kidder and Fine (Kidder and Fine 1987, p.60) describe the evolving focus of qualitative research: “A daily chore of a participant observer is deciding which question to ask next of whom.” There is no substitute for planning, practice and reflecting on what can be learnt from each interview or observation session.

Yardley(Yardley 2000, p.218), comments on the trend towards precisely defined methods:

“This trend is fuelled by the tendency of those who are new to qualitative research, and dismayed by the scope and complexity of the field, to adhere gratefully to any set of clear-cut procedures provided by proponents of a particular form of analysis.”

As noted elsewhere, there is an interdependence between methods, research questions and resources; fixed methods have their place, but can rarely be applied cleanly to address a real research problem (Furniss et al., 2011a), and may sometimes be used as labels to describe an approach that could not, in practice, conform exactly to the specified procedure.

As well as expertise in qualitative methods, the level of expertise in the study context can have a huge influence over the quality and kind of study conducted. When the study focuses on a widely used technology, or an activity that most people engage in, such as time management (e.g. Kamsin et al., 2012) or in-car navigation (e.g. Curzon et al., 2002), any disparity in expertise between researcher and participants is unlikely to be critical, although the researcher should reflect on how their expertise might influence their data gathering or analysis.

Where the study is of a highly specialised device, or in a specialist context, the expertise of the researcher(s) can have a significant effect on both the conduct and the outcomes of a study. At times, naivety can be an asset, allowing one to ask important questions that would be overlooked by someone with more domain expertise. At other times, naivety can result in the researcher failing to note or interpret important features of the study context.

Pennathur et al. (Pennathur et al. 2013, p.216) discuss this in the context of a study of technology use in an operating theatre:

“There was a possibility for bias and/or inconsistencies during identification of hazards in the [operating theatre] due to the involvement of observers with different expertise, and consequently the aspects that they may prioritise during observations.”

Domain expertise may also cause the researcher to become drawn into the on-going activity, potentially limiting their ability to record observations systematically – effectively becoming a practitioner rather than a researcher, insofar as these roles may conflict.

In preparing to conduct a study, it is important to consider the effects of expertise and to determine whether or not specific training in the technology or work being studied is required.

43.4.4 Other resources

There will be other resources and constraints that create and limit possibilities for the research design. These include the availability of equipment, funding – for example, for travel and to pay participants –, time, and suitable places to conduct research. Here, we briefly discuss some of these issues, while avoiding stating the obvious – variants on the theme of “don’t plan to use resources that you don’t have or can’t acquire!”.

Where a study takes place can shape that study significantly. Studies that take place within the context of work, home or other natural setting are sometimes referred to as ‘situated’ or ‘in the wild’ (e.g. Rogers, 2012). Studies that take place outside the context of work include laboratory studies – involving, for example, think-aloud protocol – and some interview studies – those that take place in ‘neutral’ spaces.

There are also intermediate points, such as the use of simulation labs, or the use of spaces that are ‘like’ the work setting, where participants have access to some, but not all, features of the natural work setting.

Observational studies most commonly take place ‘in the wild’, where the ‘wild’ may be a workplace, the home, or some other location where the activity of interest takes place, that is, the technology of interest is used. Interview studies may take place in the ‘wild’ or in another place that is comfortable for participants, quiet enough to record and ensure appropriate privacy, and safe for both participant and interviewer. Of course, there are also study types where researcher and participant are at-a-distance from each other, such as diary studies and remote interviews.

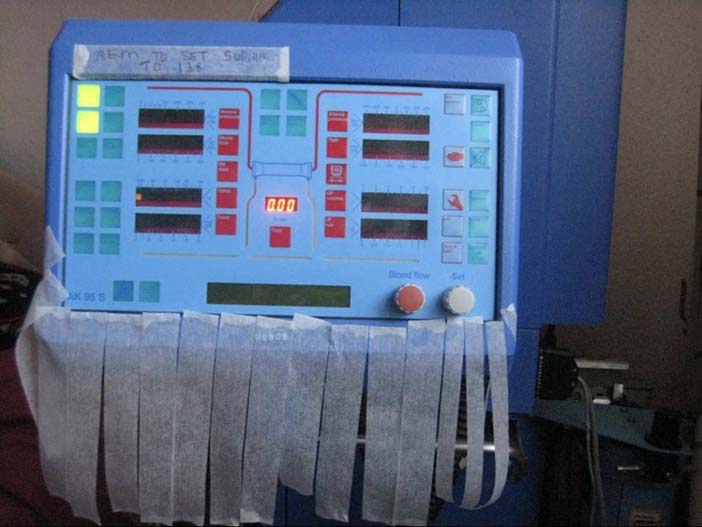

Rogers et al. (Rogers et al. 2011, p.227) discuss the uses of data recording tools including notes, audio recording, still camera, and video camera. All of these can be useful tools for data recording, depending on the situations in which data is being gathered. For instance, still photographs of equipment that has been appropriated by users, or a record of the locations in which technology was being used or how it was configured, provide a permanent record to support analysis, and to illustrate use in reports. As an example, Figure 2 shows how a home haemodialysis machine was marked up to remind the user to change a setting every time the machine was used.

Screen capture software can give a valuable record of user interactions with desktop systems. Particular qualitative methods such as the use of cultural probes (Gaver and Dunne, 1999) or engaging participants in keeping video diaries, or testing ubiquitous computing technologies, may require particular specialist equipment for data gathering. When it comes to data analysis, coloured pencils, highlighter pens and paper are often the best tools for small studies. For larger studies, computer-based tools to support qualitative data analysis (e.g. NVivo or AtlasTI) can help with managing and keeping track of data, but require an investment of time to learn to use them effectively.

Author/Copyright holder: Atish Rajkomar. Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 43.2: HHD machine with reminder “rem to set sodium to 136”. The strips hanging at the bottom also show how the machine is being used as a temporary place to store cut strips for future use.

In addition to the costs of equipment, the other main costs for studies are typically the costs of travel and participant fees. Within HCI, there has been little discussion around the ethics and practicality of paying participant fees for studies. In disciplines where this has been studied, most notably medicine, there is little agreement on policy for paying participants (e.g. Grady et al., 2005; Fry et al., 2005). The ethical concerns in medicine are typically much greater than those in HCI, where the likelihood of harm is much lower. In HCI, it is common practice to recompense participants for their time and any costs they incur without making the payment, whether cash or gift certificates, so large that people are likely to participate just for the money.

43.5 Ethics and informed consent

Traditionally, ethics has been concerned with the avoidance of harm, and most established ethical clearance processes focus on this. ‘VIP’ is a useful mnemonic for the main concerns, Vulnerability, Informed consent, and Privacy:

Vulnerability: particular care needs to be taken when recruiting participants from groups that might be regarded as vulnerable, such as children, the elderly, or people with a particular condition (illness, addiction, etc.).

Informed consent: where possible, participants should be informed of the purpose of the study, and of their right to withdraw at any time. It is common practice to provide a written information sheet outlining the purpose of the study, what is expected of participants, how their data will be stored and used, and how findings will be reported. Depending on the circumstances, it may be appropriate to gather either written or verbal informed consent; if written, the record should be kept securely, and separately from data. With the growing use of social media, and of research methods making use of such data, from, for example, Twitter or online forums, there are situations where gathering informed consent is impractical or maybe even impossible; in such situations, it is important to weigh up the value of the research and means of ensuring that respect for confidentiality is maintained, bearing in mind that although such data has been made publicly available, the authors may not have considered all possible uses of the data and may feel a strong sense of ownership. If in doubt, discuss possible ethical concerns with local experts.

Privacy and confidentiality should be respected, in data gathering, management and reporting.

Willig (Willig 2008, p.16) lists informed consent, the avoidance of deception, the right to withdraw, debriefing, and confidentiality as primary considerations in the ethical conduct of research.

However, the work of the author and co-workers with clinicians and patients (Furniss et al., 2011b; Rajkomar & Blandford, 2012, Rajkomar et al., 2013) has highlighted the fact that ethics goes beyond these principles. It should be about doing good, not just avoiding doing harm. This might require a long-term perspective: understanding current design and user experiences to guide the design of future technologies. That long-term view may not directly address the desire of research participants to see immediate benefit.

What motivates an individual technology user to engage with research on the design and use of that technology? Corbin and Strauss (2008) suggest that one reason for participating in a study may be in order to make one’s voice heard.

This is not, however, universally the case. For example, in one of our studies of medical technologies (Rajkomar et al., 2013), participants were concerned to be seen as experts – because they might have had rights withdrawn if they were not – so it was not a benefit to them to have a chance to critique the design and usability of the system. For such participants, it may be about the ‘common good’: about being prepared to invest time and expertise for long-term benefits. For others, there is an indirect pay-back in terms of having their expertise and experience recognised and valued, or of being listened to, or having a chance to reflect on their condition or their use of technology.

If the study involves using a novel technology, there may well be elements of curiosity, opportunities to learn, and experiencing pleasure in people’s motivations for taking part. Some people will be attracted by financial and similar incentives. There are probably many other complex motivations for participating in research. As researchers, we need to understand those motivations better, respect them, and work with them. Where possible, researchers need to ‘repay’ participants and others who facilitate research, and manage expectations where those expectations may be unrealistic – such as having a fully functioning new system within a few months.

Finally, Rogers et al. (Rogers et al. 2011, p.224) point out that the relationship between researcher and participants must remain “clear and professional”. They suggest that requiring participants to sign an informed consent form helps in achieving this: true in some situations, but not in others, where verbal consent may be less costly and distracting for participants.

43.6 Techniques for data gathering

The most common techniques for data gathering in SSQSs are outlined below: observation; contextual inquiry; semi-structured interviews; think-aloud; focus groups; and diary studies. The increasing focus on the use of technologies while mobile, in the home, and in other locations are leading to yet more ways of gathering qualitative data. As Rode (Rode 2011, p.123) notes:

“As new technologies develop, they allow new possibilities for fieldwork – remote interviews, participant-observation through games, or blogs, or virtual worlds, and following the lives of one’s informants via twitter.”

The possibilities are seemingly endless, and growing. The limit may be the imagination of the research team.

Whatever methods of data gathering are employed, it is wise to pilot test them before launching into extensive data gathering – both to check that the data gathering is as effective as possible and to ensure that the resulting data can be analysed as planned to address the purpose of the study. If the study design is highly iterative (e.g. using Grounded Theory as outlined in Section 1.5), then it is important to review the approach to data gathering before every data-gathering episode. If the data gathering and analysis are more independent, as in some other research designs, it is more important to include an explicit piloting stage to check that the approach to data gathering is working well: for example, to ensure that interview questions are effective or that participant instructions are clear).

43.6.1 Observation

There are many possible forms of observation, direct and indirect. Flick (Flick 2009, p.222) proposes five dimensions on which observational studies may vary:

Covert vs. overt: to what extent are participants aware of being observed?

Non-participant vs. participant: to what extent does the observer become part of the situation being observed?

Systematic vs. unsystematic: how structured are the observation notes that are kept?

Natural vs. controlled context: how realistic is the environment in which observation takes place?

Self-observation vs. observation of others: how much attention is paid to the researcher’s reflexive self-observation in data gathering?

In other words: there is no single right way to conduct an observational study. Indeed, the way it is conducted will often evolve over time, as the researcher’s understanding of the context and ability to participate constructively and helpfully in it develop.

Flick (Flick 2009, p.223) identifies seven phases for planning an observational study:

Selection of setting(s) for observation;

Determining what is to be documented in each observation;

Training of observers (see discussion on expertise, Section 4.3)

Descriptive observations to gain an overview of the context;

Focused observations on the aspects of the context that are of interest;

Selective observations of central aspects of the context;

Finish when theoretical saturation has been reached – i.e., when nothing further is being learned about the context.

These phases – particularly selective observations and theoretical saturation – convey a particular view of observation as developing a focused theory, much in the style of Grounded Theory (Section 1.5). Nevertheless, the broader idea of careful preparation for a study and recognition that the nature of observations will evolve over time are important for nearly all observational studies.

Willig (Willig 2008, p.28) discusses the nature of data gathering, including the importance of keeping detailed notes – such as near-verbatim quotations from participants and “concrete descriptions of the setting, people and events involved”. She refers to these as “substantive notes”, which may be supplemented by “methodological notes” – reflecting on the method applied in the research in practice – and “analytical notes”, which constitute the beginning of data analysis (Section 7). She also notes that data collection and analysis may be more or less tightly integrated – a theme to which we return in Section 9.3.

43.6.2 Contextual Inquiry

Contextual inquiry (Beyer and Holtzblatt, 1998) is a widely reported method for conducting and recording observational studies in HCI, as a stage in a broader process of contextual design. According to Holtzblatt and Beyer (2013), “Contextual Design prescribes interviews that are not pure ethnographic observations, but involve the user in discussion and reflection on their own actions, intents, and values”. In other words, contextual inquiry involves interleaving observation with focused, situated interview questions concerning the work at hand and the roles of technology in that work.

More importantly, Holtzblatt and Beyer (2013) present clear principles underpinning contextual design, and a process model for conducting design, including the contextual inquiry approach to data gathering. This includes a basic principle of the relationship between researcher and participants: that although the researcher may be more expert in human factors or system design, it is the participants who are experts in their work and in the use of systems to support that work.

Holtzblatt and Beyer (2013) present five models, flow, cultural, sequence, physical, and artefact, that are intermediate representations to describe work and the work context, and for which contextual inquiry is intended to provide data. Although contextual inquiry is often regarded as a component of contextual design, it has been applied independently as an approach to data gathering in research (e.g. Blandford and Wong, 2004).

43.6.3 Think Aloud

In contextual inquiry, the researcher is clearly present, shaping the data gathering through the questions he or she asks; in contrast, in a think-aloud study the researcher retreats into the background. Think aloud involves the users of a system articulating their thoughts as they work with a system. It typically focuses on the interaction with a particular interface, and so is well suited to identifying strengths and limitations of that interface, as well as the ways that people structure their tasks using the interface. Think aloud is most commonly used in laboratory studies, but also has a valuable role in some situated studies, as people demonstrate their use of particular systems in supporting their work (e.g. Makri et al., 2007).

Variants on the think-aloud approach are used in many disciplines, including cognitive psychology (e.g. Ericsson and Simon, 1980), education research (e.g. Charters, 2003) and HCI. Boren and Ramey (2000) conducted a review analysing the ways in which think aloud had been used in a variety of HCI studies, and conclude that, although most researchers cited Ericsson and Simon (1980) as their source for the method, the details of think alouds varied substantively from study to study.

Boren and Ramey (Boren and Ramey 2000, p.263) highlight four key principles from Ericsson and Simon (1980) to which a think aloud study should conform:

Only ‘hard’ verbal data should be collected and analysed: “The only data considered must be what the participant attends to and in what order.”

Detailed instructions for how to think aloud should be given: “Encourage the participant to speak constantly ‘as if alone in the room’ without regard for coherency.” They also recommend that participants should have a chance to practise thinking aloud prior to the study.

If participants fall silent, they should be reminded succinctly to verbalise their thoughts.

Other interventions should be avoided, and attention should not be drawn to the researcher’s presence. This is in stark contrast to the approach of contextual inquiry (section 6.2).

Norgaard and Hornbaek (2006) conducted a study of how think aloud methods are used in practice, observing studies in seven different companies. They noted (p.271) that many of the studies did not conform to the guidelines above. For example, they included questions about people’s perceptions, expectations, and interpretations during the TA study; exhibited a “tendency that evaluators end up focusing too much on already known problems”; and “evaluators seem to prioritize problems regarding usability over problems regarding utility”.

In other words, as with most other data-gathering techniques, there are in practice many different ways to go about gathering data, and these are shaped by the interests of the researcher, the purpose of the study, and the practicalities of the situation.

One aspect of think aloud that has received little attention is how participants are instructed – not just in how to think aloud, but also in the tasks to be performed. Sometimes (e.g. Makri et al., 2007) these are naturalistic tasks chosen by the participants themselves, so that the researcher is essentially observing the participant completing a task that is part of, or aligned to, their on-going work. In other cases, tasks need to be defined for participants, and care needs to be taken to ensure that these tasks are appropriate, realistic and suitably engaging. While researcher-defined tasks are widely used in usability studies, they are less common in SSQSs, which are generally concerned with understanding technology use ‘in the wild’.

43.6.4 Semi-structured Interviews

Think alouds are one way to gather verbal data from participants about the perceptions and use of technology; interviews are another widespread way of gathering verbal data. Interviews may be more or less structured: a completely structured interview is akin to a questionnaire, in that all questions are pre-determined, although a variety of answers may be expected; a completely unstructured interview is more like a conversation, albeit one with a particular focus and purpose. Semi-structured interviews fall between these poles, in that many questions – or at least themes – will be planned ahead of time, but lines of enquiry will be pursued within the interview, to follow up on interesting and unexpected avenues that emerge.

Interviews are best suited for understanding people’s perceptions and experiences. As Flick (Flick 1998, p.222) puts it: “Practices are only accessible through observation; interviews and narratives merely make the accounts of practices accessible.”

People’s ability to self-report facts accurately is limited; for example, Blandford and Rugg (2002) asked participants to describe how they completed a routine task, and then to show us how they completed it. The practical demonstration revealed many steps and nuances that were absent from the verbal account: these details were taken for granted, so ‘obvious’ that participants did not even think to mention them.

Arthur and Nazroo (2003) emphasise the importance of careful preparation for interviews, and particularly the preparation of a “topic guide” (otherwise known as an interview schedule or interview guide). Their focus is on identifying topics to cover rather than particular questions to ask in the interview. It can be useful to have prepared important questions ‘verbatim’ – not because the question should then be asked rigidly as prepared, but because it identifies one way of asking it, which is particularly valuable if the interviewer has a ‘blank’ during the interview. Arthur and Nazroo advocate planning the topic guide within a frame comprising:

Introduction;

Opening questions;

Core in-depth questions; and

Closure.

This planning corresponds to the stages of an interview process as described by Legard et al. (2003), who present two views on in-depth interviewing. One starts from the premise that knowledge is ‘given’ and that the researcher’s task is to dig it out; although they do not use the term, this is in a positivist tradition. The other view is a constructivist one: that knowledge is created and negotiated through the conversation between interviewer and interviewee. Legard et al. (Legard et al. (2003) p.143) emphasize the importance of building a relationship, noting that the interviewer is a “research instrument”, but also that researchers need “a degree of humility, the ability to be recipients of the participant’s wisdom without needing to compete by demonstrating their own.”

They present the interview process as having six stages, all of which need to be planned for:

Arrival: the first meeting between interviewee and interviewer has a crucial effect on the success of the interview; it is important to put participants at their ease.

Introducing the research: this involves ensuring that the participant is aware of the purpose of the research, and has given informed consent, that they are happy to have the interview recorded, and understand their right to withdraw.

Beginning the interview: the early stages are usually about giving the participant confidence and gathering background facts to contextualize the rest of the interview.

During the interview: the body of the interview will be shaped by the themes of interest for the research. Participants are likely to be thinking in a focused way about topics that they do not normally consider in such depth in their everyday lives.

Ending the interview: Legard et al. emphasize the need to signal the end so that the participant can prepare for it and ensure there are no loose ends.

After the interview: participants should be thanked and told what will happen next with their data. Many participants think of additional things to say once the recorder is off, and these may be noted. Legard et al. emphasise the importance of participants being “left feeling ‘well’” (Legard et al. (2003) p.146), as discussed in section 5.

Legard et al. present various strategies for questioning, including the use of broad and narrow questions, avoiding leading questions, and making sure all questions are clear and succinct.

Within the core phase of interviewing, one technique to help with recall is the use of examples, asking people to focus on the details of specific incidents rather than generalizations. For example, the critical incident technique (Flanagan, 1954) can be used to elicit details of unusual and memorable past events, which in the context of HCI might include times when a technology failed or when particular demands were placed on a system.

A variant of this approach, the critical decision method (CDM), is presented in detail by Klein at al. (1989): in brief, their approach involves working with participants to reconstruct their thought processes while dealing with a problematic situation that involved working with partial knowledge and making difficult decisions. CDM helps to elicit aspects of expertise that are particularly well suited to studying technology use in high-pressure environments where the situation is changing rapidly and decisions need to be made, as in control rooms, operating theatres, and flight decks.

Charmaz (2006) describes an “intensive interview” as a “directed conversation”. Her focus is on interviewing within grounded theory (Section 1.5), and on eliciting participants’ experiences. She emphasizes the importance of listening, of being sensitive, of encouraging participants to talk, of asking open-ended questions, and not being judgemental. Although the participant should do most of the talking, the interviewer will shape the dialogue, steering the discussion towards areas of research interest while attending less to areas that are out of scope.

Charmaz emphasizes the “contextual and negotiated” (p.27) qualities of an interview: the interviewer is a participant in the shaping of the conversation, and therefore, the interviewer’s role needs to be reflected in the outcome of a study. This is a theme to which we return in Section 9.2.

43.6.5 Focus groups

Focus groups may be an alternative to interviews, but have important differences. The researcher typically takes a role as facilitator and shaper, but the main interactions are between participants, whose responses build on and react to each other’s. The composition of a focus group can have a great effect on the dynamic and outcome in terms of data gathered. Sometimes a decision will be made to gather data through focus groups to exploit the positive aspects of group dynamics; at other times, the decision will be more pragmatic.

For example, Adams et al. (2005) gathered data from individual practising doctors through interviews, partly because doctors typically had their own offices (a location for an interview), but also because they had very busy diaries. Each interview, therefore, had to be scheduled for a time when the participant was available (and many had to be delayed or rescheduled due to the demands of work). However, they gathered data from trainee nurses through focus groups because the nurses formed a cohort who knew each other reasonably well and often had breaks at the same time, so it was both easier and more productive to conduct focus groups than interviews.

43.6.6 Diary studies

Diary studies enable participants to record data in their own time – such as at particular times of day, or when a particular trigger occurs. Diary entries may be more or less structured; for example, the Experience Sampling Method (Consolvo and Walker, 2003) typically requires participants to report their current status in a short, structured form, often on a PDA / smart phone, whereas video diaries may allow participants to audio-record their thoughts, with accompanying video, with minimal structure.

Kamsin et al. (2012) investigated people’s time management strategies and tools using both interviews and video diaries. While interviews gave good insights into people’s overall strategies and priorities, the immediacy of video diaries delivered a greater sense of the challenges that people faced in juggling the demands on their time and of the central role that email plays in many academics’ time management.

43.6.7 Summary

Analysis can only work with the data that is collected. Therefore, it is important to gather the best possible data, working within the resources of the project (as discussed in Section 4). In some situations, data gathering and analysis are treated as being semi-independent from each other, with all analysis following the end of data gathering. In other situations, the two are interleaved – whether in the rich way advocated in GT, or by interleaving stages of data gathering and analysis as the study proceeds (e.g. as the theoretical focus develops, or as different data gathering methods are applied to address the problem from different angles – see discussion of triangulation in section 10.2).

43.7 Analysis

Most data for SSQSs exists in the form of field notes, audio files, photographs and videos. The first step of analysis is generally to transform these into a form that is easier to work with – such as transcribing audio, annotating or coding video. This may be done at different levels of detail; for example, selectively transcribing text that is directly relevant to the theme of the study through to a full transcription of all words, phatic utterances, pauses and intonations. The decision about which details to include should be guided by the purpose of the study, and hence the style of analysis to be completed. Some researchers choose to transcribe data themselves, as the very act of transcribing, and maybe making notes at the same time, is a useful step in becoming familiar with the data and getting immersed in it. Others prefer to pay a good typist to transcribe data, because, for example, they consider this a poor use of their time.

Author/Copyright holder: Courtesy of Ann Blandford. Copyright terms and licence: CC-Att-ND-3 (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported).

Figure 43.3: Reorganising Scrabble letters

Similarly, people make different decisions about which tools to use for analysis. Decisions may be based on prior experience – such as having used Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA) tools such as ATLASti or NVivo, on the size and manageability of the dataset, and on personal preference. Any tool creates mediating representations between the analyst and the data, allowing the analyst to ‘see’ the data in new ways, just as reorganising Scrabble letters can help the player to ‘see’ words they may not have noticed previously (Figure 3). One researcher may choose to use a set of tables in a word processor to organise and make sense of data; another might create an affinity diagram (see Figure 4 for an example). Corbin and Strauss (Corbin and Strauss 2008, p.xi) emphasise that tools should “support and not ‘take over’ or ‘direct’ the research process”, but note the value of tools in making analysis more systematic, contributing to reliability and an audit trail through the analysis.

Author/Copyright holder: Stawarz (2012). Copyright terms and licence: All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission. See section "Exceptions" in the copyright terms below.

Figure 43.4: Example of affinity diagramming with post-it notes, reproduced with permission from Stawarz (2012).

43.7.1 Different approaches to coding and iteratively analysing data

As noted above, an identifying feature of SSQSs is that they involve some form of coding of the data – i.e. of creating useful descriptors of units of data, such as single words, phrases, extended utterances, objects featuring in photographs, actions noted in videos, etc., and then of comparing and contrasting coded units to construct an analytical narrative based on the data. Grounded theory and thematic analysis (as outlined in Section 15 and Section 7.2) exemplify ways of coding data for analysis. There is a ‘space’ of approaches to coding qualitative data.

At one extreme, codes are simply ‘buckets’ in which to organise concepts identified in the data. Taking a utilitarian HCI approach, as a form of requirements gathering and system evaluation, CASSM (Blandford et al., 2008b; Blandford, in press) is a systematic approach to identifying the concepts that users are invoking when working with a system; where possible, these should be implemented in the system design (Johnson and Henderson, 2011).

A CASSM analysis involves gathering verbal data and classifying it in terms of user concepts. For example, in a study of ambulance control (Blandford et al., 2002), controllers were found to be working with two concepts both of which they referred to as ‘calls’: emergency calls being received; and the incidents to which those calls referred. The call management system they were working with at the time of the study allowed them to process emergency calls reasonably easily, but did not support incident management, which is important, particularly when a major incident occurs and many people call to report the same incident. A CASSM analysis is an SSQS, but the data analysis is simple, being mainly concerned with coding concepts by assigning them to ‘buckets’.