It might seem like it’d be a one-time journey if you’re going to step into the shoes of a UX designer and that once you’re “there,” you’re there as one—end of story. But it’s not like that; it’s very much a process, and an ongoing one at that. We hope this doesn’t blow your image of what it might look like to be in this exciting “job description”; if anything, we’re eager to share tons of great information with you now so you can make the most of what is an extremely rewarding career—and process—so, stick around and be sure to read on as you learn all about how you can become the best UX designer by keeping on becoming the best UX designer you can be!

Table of contents

- What is a UX Designer?

- Always Becoming a UX Designer

- How to Become a UX Designer?

- Do the Craft of UX Design

- Communicate Brilliantly

- Embrace Complex and Wicked Problems

- Learn to Learn

- Possible Career Paths of a UX Designer

- The Power of Networking as a UX Designer

- How Do You Create a Better UX Design Portfolio?

- The Take Away

- References and Where To Learn More

- Images

What is a UX Designer?

A UX designer is who’s responsible for crafting user experiences for digital products—like websites and apps—and they’re focused on understanding exactly what users need and what they enjoy. Right now, just think of an app which you love using—one of your favorites, if not the favorite—well, a UX designer has carefully planned out your experience with it. They decide everything—as in, right down to all the fine details—from what features will help you get to and get through your goals to how those features work, how you get information, and the tiny details—such as button placement, color schemes, and font sizes. It’s a role that nicely combines visual appeal with functional design, and—what’s more—it delves neatly into user psychology.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

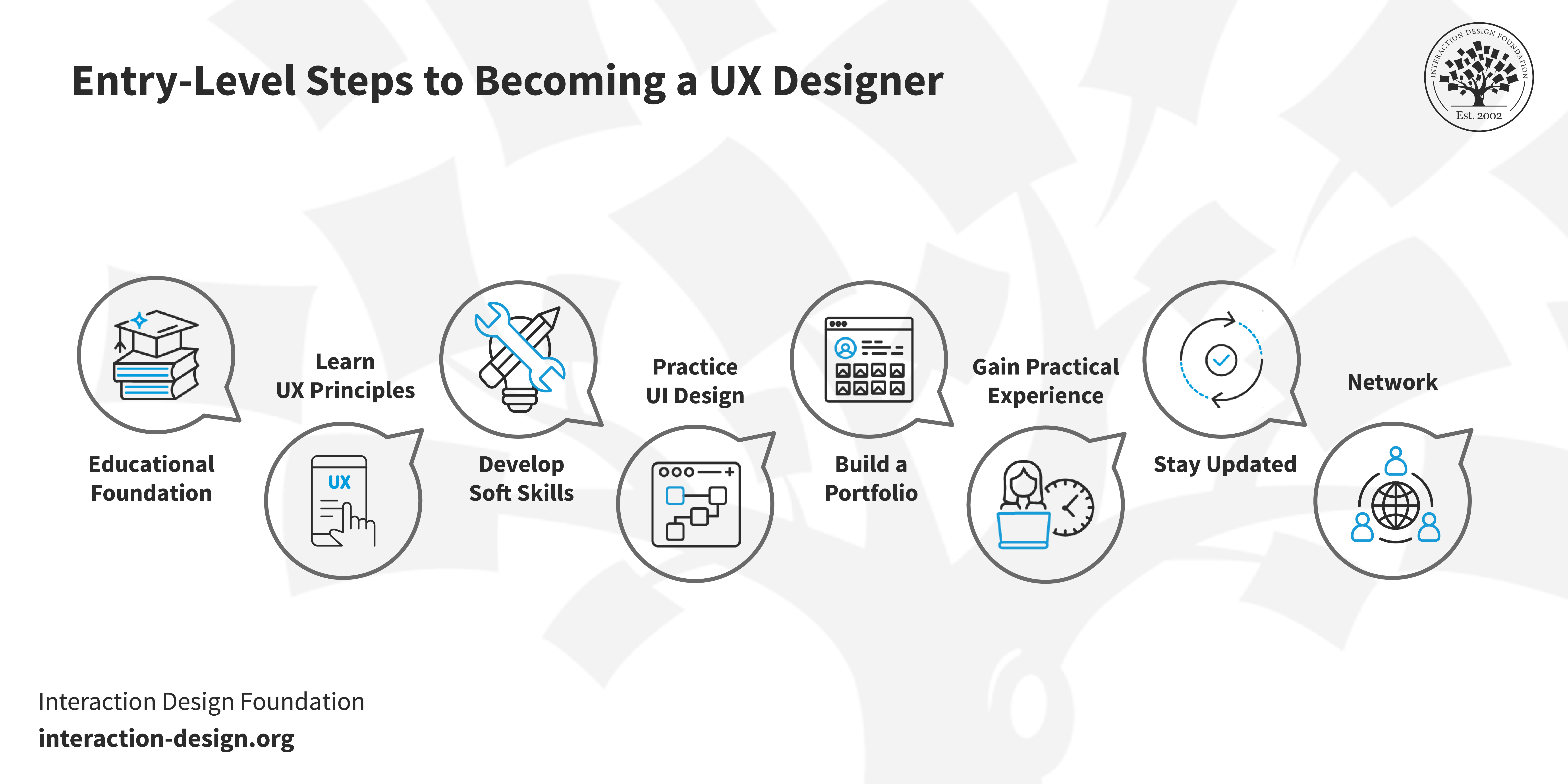

We’re going to examine elements such as the value of networking and a powerful portfolio a little later, but here are some core considerations to bear in mind now. To start with, it’s important to know how to start becoming a UX designer. A good education will build a solid foundation. While many companies don’t insist on formal education or a degree in design-related fields, you can pursue computer science, design, or human-computer interaction education—and a decent education is one that’ll provide you with a good, solid, theoretical understanding of key concepts.

It’s also vital to build up your knowledge of user interface (UI) principles. Get good at UI design and it’ll help you as a UX designer. The focus with that is on the design of user interfaces for software and digital products, and the core piece of that focus lies in making the design user-friendly and accessible—two terms that are pretty much precious beyond measure in design.

Content is massively important, so watch as Frank Spillers, CEO of Experience Dynamics sheds light on the importance of content and how to organize it to get better results.

What’s more, it’s vital to practice UI design, which includes getting proficient at the tools as well as what you know. Designers use these tools to create wireframes, prototypes, and designs for digital products and web development—so get to know how to use these. A solid background in visual design skills and knowing how to make effective information architecture (IA), as in structuring and organizing content, is important.

Another point that’s precious to focus on early on is soft skills mastery and you’ll need good soft skills to succeed as a UX designer, too. As skills, they’re essential as far as understanding user needs and creating effective, user-centered design solutions goes—as in, exceedingly essential.

On the journey on the long and interesting road of UX design, you’ll pick up, hone and polish, and combine knowledge of human-computer interaction, design principles, and technical skills that you’ll need to do well in the UI/UX world and resonate with the users of the brands whose products you’ll work on.

UX designers are creative problem-solvers, and a chief aim that they’ve got is to balance aesthetic appeal with practicality. What’s their goal, exactly? It’s to make user interactions smooth and enjoyable. They make every design choice—and that goes from button size to checkout flow—deliberately and so that it’s focused on the user. An important point to make here is that this dynamic and creative field evolves as technology and user expectations evolve, themselves.

Always Becoming a UX Designer

As a phrase "become a UX designer" might seem easy to read, nice and straightforward a concept and one that’s a direct A-B trip; and you may picture a one-time journey. It’s vital to step in here and point out, though, that it’s a process and an ongoing one at that.

Becoming a UX designer is a one-time journey.

... but really it is an ongoing process.

Always becoming a UX designer is an ongoing process.

You won’t find an end to the process, just improvement—but don’t feel dispirited if that might seem like a long, hard road to get on. A lot of it really comes down to how you see it; and here’s a good way to envision the realities that are involved here.

There are two undeniably important reasons as to why a UX designer never stops—or at least should never stop—becoming one:

As a UX designer, you often face problems that happen to be intertwined with several factors, and they’re things that tend to characterize real-world or human problems (as in, ones that tend to be the most worth solving for real people in the world). You may find an issue, for example, that’s related to the latest technologies, cultural forces, and the world's current state (yes, including political and economic forces that helped take it to that state). That’s the human world, for you, and these elements are things that change constantly—and will continue to.

You’re going to have to adapt your skills, knowledge, methods, and tools so you can really influence and improve these situations.

For example—and we’re going to do some time-traveling envisioning here—imagine someone’s just asked you to design a mobile commuting app, and the year is 1999.

A mobile commuting app on a 1999 mobile device.

First things first—you’d have to understand how to design for small screens and with slow data speeds. But—and in keeping with that era—you would not have understood micro-mobility (think electric scooters and bikes here), self-driving cars, or digital payments, and certainly not at the level that these things have become realities in the 2020s. And there’s something else: you’d have used Adobe Photoshop to create the screen designs.

Now, imagine someone who’s been asked to design the same app in the year 2030—a three-decade jump from 1999. Small screens and slow data speeds aren’t an issue any longer, but you probably will have to understand micro-mobility, self-driving cars, and digital payments. And you’re probably no longer going to be using Adobe Photoshop but some other tool for the design of it.

A mobile commuting app on a 2030 mobile device.

How to Become a UX Designer?

At this point—and after jumping a couple of “time zones” for our little imagination exercise, you may well be wondering, “If there are no specific steps that will lead me to the destination of UX designerhood, then what’s all this about?”

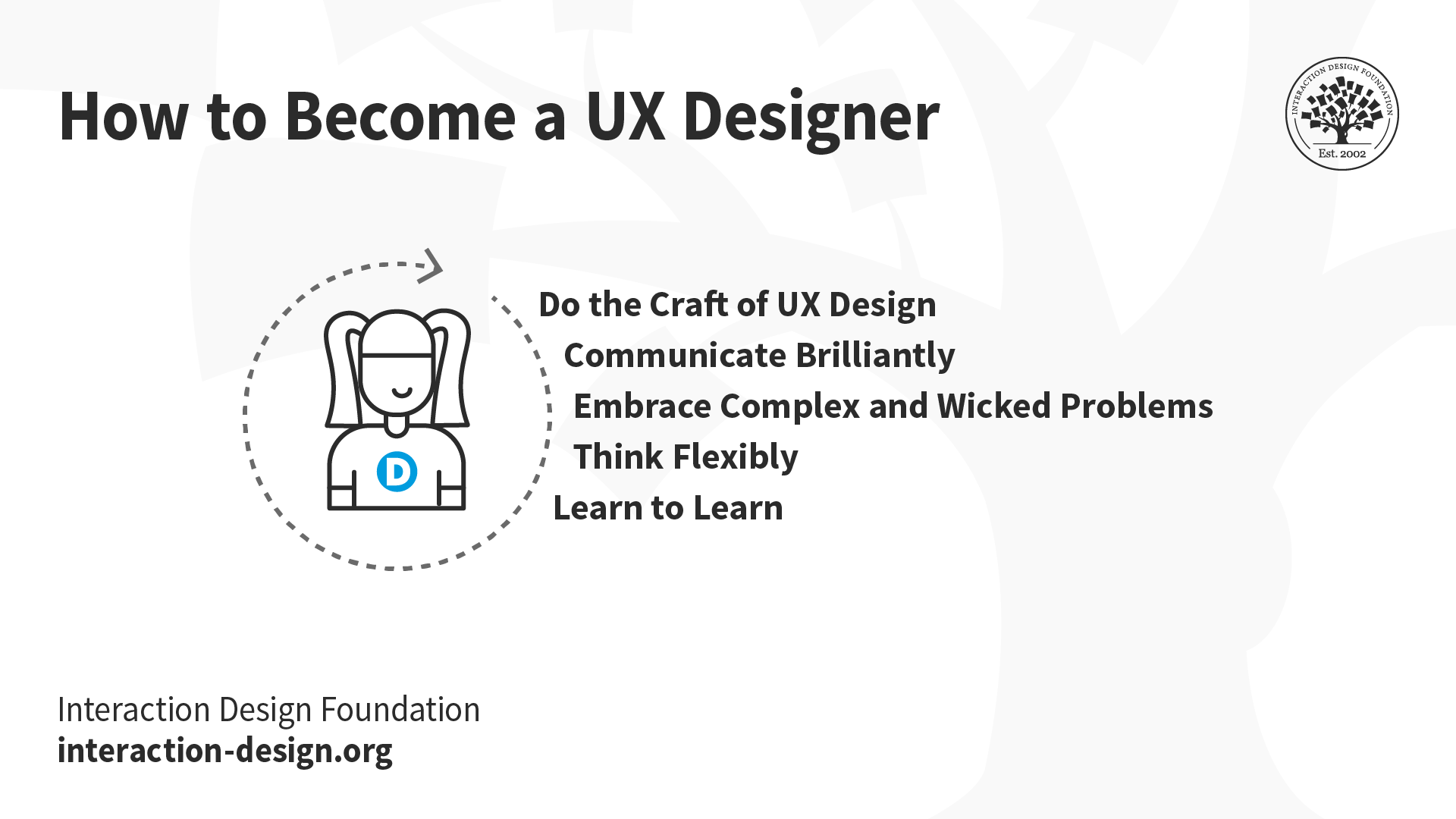

Well, what all this has to do with is this neat and convenient little point: There are five things that you can focus on throughout your career that are going to help you to become the best UX designer you can be! Note that one of the keywords there is “throughout”; it kind of helps bring it into a nice and healthy perspective—a “living thing” of a career.

Five things you can focus on throughout your career to become the best UX designer you can be.

Do the Craft of UX Design

To start with, let’s get right to the most obvious thing you can do to improve as a UX designer: Do the craft of UX design as often as you possibly can.

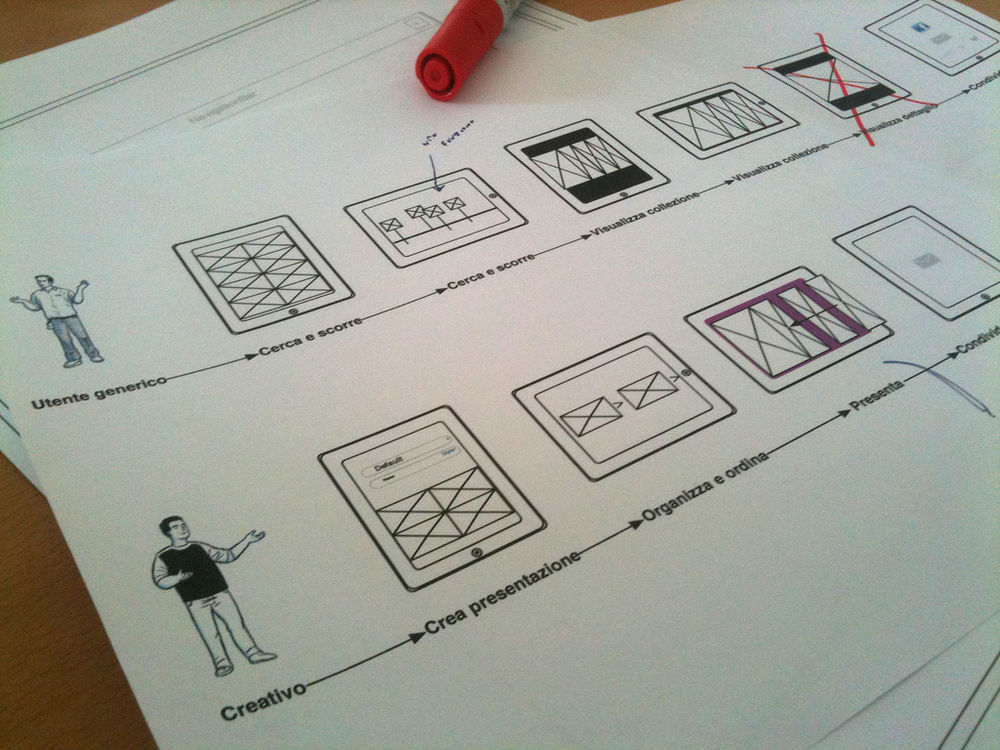

Every day, look for opportunities to learn and master the tools of UX—and here we’ve got things like pen and paper, Sketch, and Figma, the list goes on. Take these tools and use them to create artifacts like sketches, flowcharts, wireframes, mockups, prototypes, and design documentation. And, as often as you can manage to, it’s pretty important to familiarize yourself with UX design processes such as user research, user testing, and design critique.

Do the craft of design — master the tools, create artifacts and learn the processes — every day.

It’s a good thing to keep in mind that these opportunities aren’t things that happen at work or chances that pop up in a design course; no, they happen every day, all around you. Do you remember that unusable app that made you feel like tearing your hair out—or yell at it while you were on the phone with someone who wondered just how bad it must be—because it was that bad? Well, try to find out what the root problem is—and no pun intended on “root” with hair—and then go sketch a better version. You’ll get bonus points for testing your improved version on a friend. Do you overhear complaints at your company or where you work about a system or a process that some people there can’t stand? Have conversations with those folks who are affected, identify what’s causing their frustration, and then—we might have a drumroll here—design a solution, or two; or three.

Let’s think about something else for a moment: how, as a UX designer, your craft is rather like what a carpenter does. Let’s think about this for a moment—about how a good carpenter may look like a fully “developed” professional in the skills department, but how that person actually hones skills, continuously. These skills, by the way, are things like taking room measurements, doing project estimates, using tools, and expanding their creative range. And, just like that carpenter, you’ve got to constantly practice your craft if you’re going to well and truly improve it.

Communicate Brilliantly

Let’s get away from the technical-skillsy side and look hard at this one—a less obvious skill but a vital one you’ve got to have all the same. Effective communication is an essential thing in all roles, and that’s especially the case in UX design work, which sits at the heart of a larger process, and it starts after new needs, ideas, or business cases get identified—before moving on to testing and deploying the designed experience.

As a UX designer, your ability to communicate will help everyone.

So, what exactly can you do to communicate brilliantly in UX design and really reach people so they understand, trust, act upon what you’ve told them, and respond properly to your input? You may well have already guessed, but now we’ll home in on the four key things you can do:

1. Make It Understandable

When you’re communicating with a stakeholder, a developer, or another designer, it’s vital to learn their specific terminology (that’s if you don’t already know the terms; if you do, then use these appropriately). Visual communication—for example, through flowcharts, diagrams, and mockups—can help them understand exactly what you’re proposing to do.

2. Help People Trust the Logic

Every napkin sketch, every high-fidelity mockup, every whatever-it-is-of-this-sort is a proposal for some kind of change in the world. But what something like a sketch might belie—say, due to its simplicity—is that these changes call for effort, investment, and some risk. When you’re working on creating these, it’s vital to always include a strong rationale—research, data, evidence—so that someone who’s to see it can really trust that the effort’s going to be worth it.

3. Help People Get Behind It

Brilliant communication goes way beyond appealing just to logic alone—it appeals to emotion, too. And that’s why you don’t just include a strong rationale in your UX design communications; put in stories, images, and evidence that appeal to people, too.

4. Make It Actionable

UX design communication has often got a big focus on action to change the world, and so, you’ve got to communicate your messages clearly and indicate what the next steps to take—or which ones to avoid—are.

Being at the center of and collaborating with different departments does bring its share of challenges, to be sure. And those aren’t the only complex situations you’re going to find yourself in.

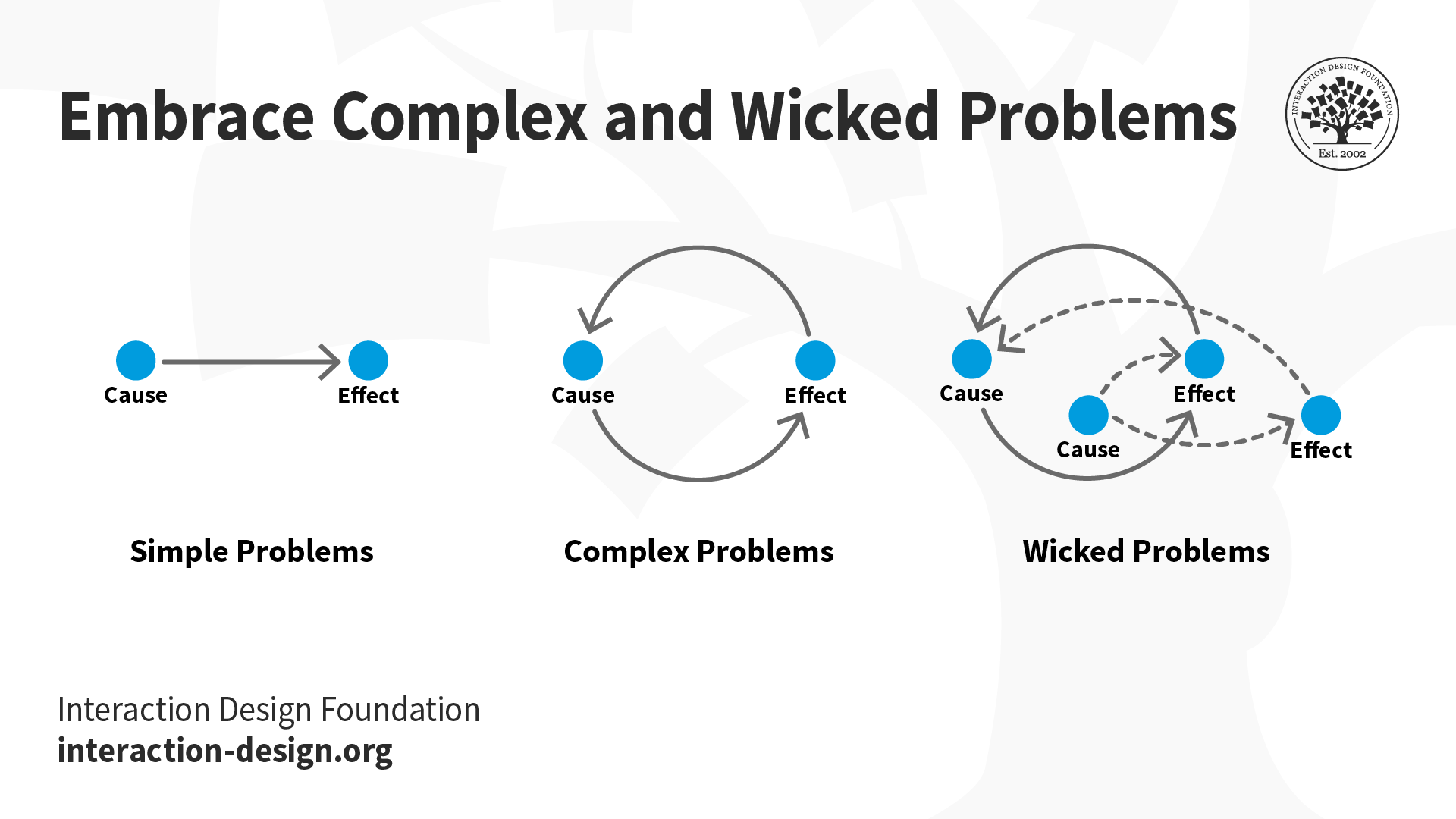

Embrace Complex and Wicked Problems

If you’re going to consistently become the best UX designer that you can be, you’ve got to not just tolerate but embrace too the idea of working on problems that are difficult.

It’s fair to say that you can tell a professional by what kind of challenges they embrace. Experienced auto mechanics, let’s take as an example, love the challenge of fixing up an old car, and they’ve usually got the grease under their fingernails to prove it. Shake a farmer's hand, and you’ll very likely be able to feel the strength of working with the earth and animals, and any calluses on that hand will more than corroborate it.

You may not see it—or feel it—in their handshake, but experienced UX designers tend to be more than a little passionate about understanding and solving problems—and, like mechanics and farmers, they often enjoy tackling challenging problems. In keeping with the farmer side of things there, it’d be fair to say that UX designers actually cultivate solutions in the “soil” of problems.

Problems, problems—you’re going to encounter many throughout your UX design career as you build up your expertise. But it’s a key thing to work on a variety of problems, especially challenging ones, so you can start to tell the difference between them and enjoy taking them on and getting into what’s behind them; and here are three common types: Simple, Complex, and Wicked problems.

UX designers are asked to solve simple, complex and often wicked problems.

Simple Problems

A simple problem—which is often called "clear," "obvious," "tame," or "trivial"—has a straightforward definition. It involves an easily traceable cause and effect with a testable solution; so, things are nice and, true to the name, simple. Things like how to create a louder violin, a faster car, or an eye-catching advertisement—they’re problems that might be challenging, sure; that said, though, it’s relatively easy to understand the steps that’ll get you to the desired effect.

Complex Problems

Let’s switch things up a bit now and stick a complex problem under our “microscope” here; these ones have got a less clear definition and multi-directional cause-and-effect chains to them. Plus, they’ve got solutions that you may well find harder to test than ones for the good old simple problems. Let’s picture, as an example, how to make a digital experience for collaborative student learning. These problems can be way more challenging to solve, and—as if that weren’t enough to have to grapple with—it's hard to actually pinpoint what the exact problem is and pick the causes from effects, let alone get on to determine what the successful solution’s going to look like.

Wicked Problems

The word “wicked” might conjure scary imagery for some people—and, to be fair, some of these problems can look extremely daunting—but “wicked problems” are a thing, and a wicked problem may well have multiple definitions, explanations of cause and effect, and no immediately testable solutions. Below, we’ve got some examples of wicked problems:

Poverty and homelessness.

Improving educational outcomes.

Climate change.

We want to share this with you, not to scare you off, but so you’ve got a good head start on the rest of your UX journey, and—this way—you can notice different problems around you every day.

Professor Alan Dix, Author and Expert in Human-Computer Interaction, discusses wicked problems and how important it is to understand problems in your work.

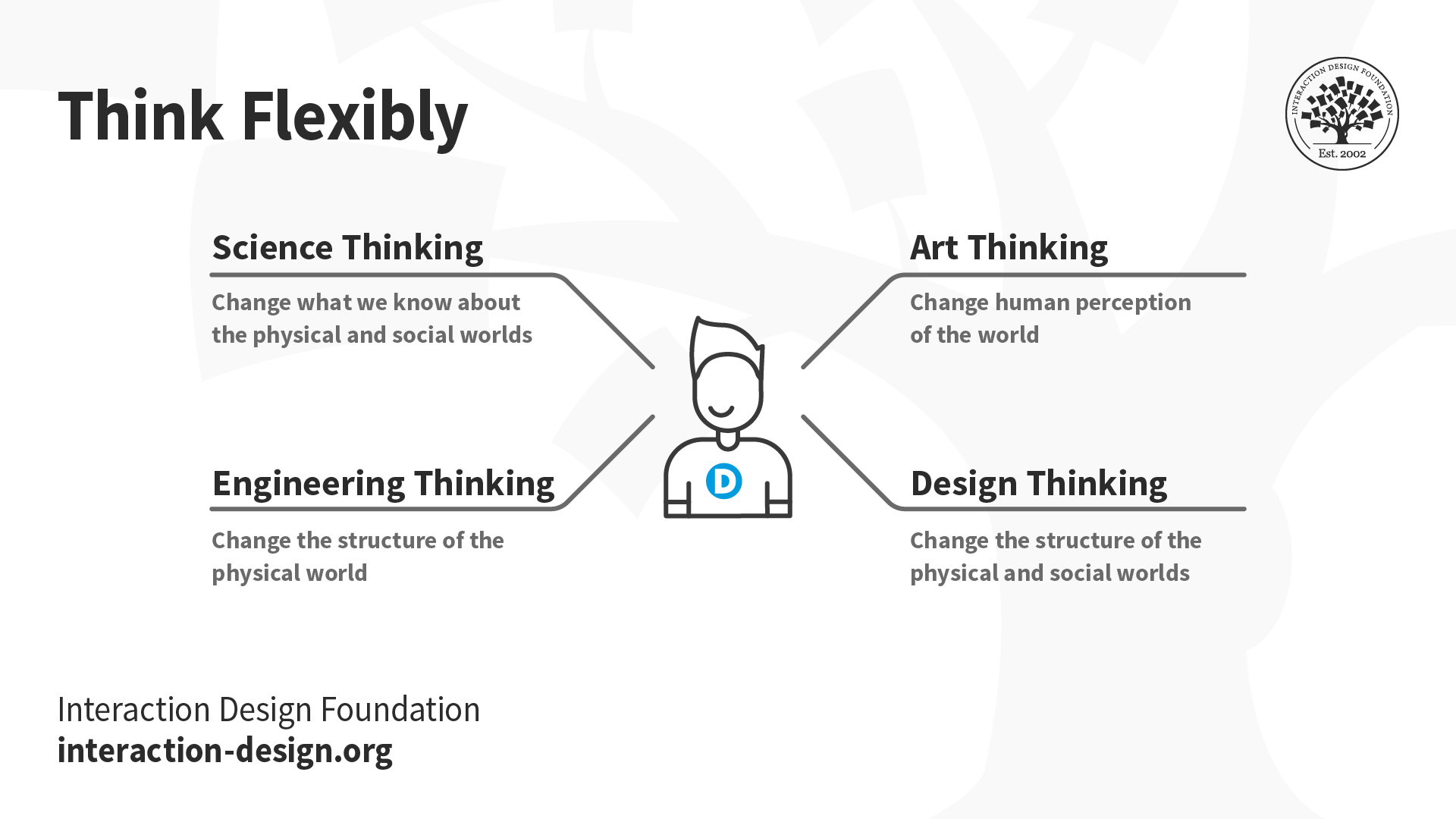

Think Flexibly

A UX designer has got to think flexibly if they’re going to solve complex problems and communicate across disciplines to help get them solved, and—with flexibility in mind—you’ve got to use different types of thinking for different purposes. If you’ve ever heard the term design thinking, then you may well think it’s the only way for designers to get problems out in the open and really solve them. But its actually just one among many, and here we’re going to consider four of them. The other three we’ll call convenience engineering thinking, art thinking, and science thinking.

Thinking Types | Typical Methods | Primary Goal | Core Assumptions |

Iteration, process, exploration | Changes the physical and social world to create value. | You can create value and not discover it. | |

Engineering Thinking | Physics, math, process, and material construction | Change the physical world. | You can discover and change the facts about the physical world. |

Art Thinking | Media, aesthetics | Change human perception. | You can change the perception. |

Science Thinking | Scientific method | Change knowledge of the physical and social world. | You can observe and discover facts. |

To start off with, let’s take a practical example: Imagine someone’s just given you the budget not just to design a mobile app but create a really large internet-connected digital sign right in the center of a big city, too. The goal here is to improve people’s perception of public transportation and make the number of people who actually use it every day go up—a nice little energy saver, too, as they won’t all be in their own cars, for example.

It’s a really big project—and it’s one that’s got many challenges and many decisions to make to get things sorted out best. So, now, let’s think about some things here, starting with what can you design and build to actually change people’s perceptions and behaviors? What sort of interface are you going to need? Is data going to flow between the app and the billboard? And, if that’s to be the case, how? And how are you going to test it and iterate on it? And—last but not least here—how’re you going to know for sure that your design has achieved its goals?

This is where flexible thinking is going to be a great help. Think of it like putting on different pairs of glasses, where each one lets you see different parts of the problem.

Your ability to think flexibly will help you solve complex and wicked problems.

You might start with art thinking as you consider how people perceive public transportation and how you might go about changing it. Let’s see here—would heroic images on the billboard change perception? What about personal public transit stories from app users, themselves? Might some humor change perception about this? You don’t need to be an artist to employ art thinking, but it’ll help if you think like one!

Let’s imagine you’ve decided to use social pressure by letting public transport people post fun photos of themselves on the billboard. You put your design thinking “glasses” on and realize that you’ve got to really understand the people in this real city before you can get to designing a solution.

So, off you go to do some user research, prototype your idea, and test it. You put on your engineering thinking glasses—and you’ll ask and address questions about how the photos will go from app to billboard, where you’ll store the images, and the resolution of a billboard. Then, as the project nears launch, science thinking is what helps you collect the data you’ll need to help you understand if—as well as how—your solution worked.

This example doesn’t accurately represent reality; it can’t, of course—it’s more to illustrate something important to understand. In a real project, you’d take many more steps, involve people, and think in a more non-linear order.

What it does represent is how flexible thinking—that ability to approach a problem from multiple angles—is a skill that’s truly crucial for you as a UX designer.

Learn to Learn

The last—and, sure, the most important—thing you can do to become the best UX designer you can be is to learn how to learn, or at least learn better than you’re maybe already managing to. “Learn to learn” may sound a familiar nugget of wisdom, but learning skills are indeed the magic multiplier of all the other skills.

It might sound like a bit of a truism, but it’s indeed true that learning also lets you more easily grasp and combine new flexible ways of thinking. And, what’s more, it can help you to analyze and address complex and wicked problems—and so put you in a more capable position to do things.

There isn’t any magic method for learning, but you should pay close attention to—and develop—the best methods that work for you. For example, many people find that taking hand-written notes—in notebooks, in the margins of books, or digital format when they use a stylus—really helps solidify their knowledge. Others use digital apps to keep typed notes that are both taggable and searchable. Many people learn best in structured courses or boot camps, while others find they’ll learn best from short video tutorials or blog posts; we’re all different—and, for how people go about learning in the ways that are best for them, the list of methods is pretty much endless.

As a UX designer, constant learning is part of your role.

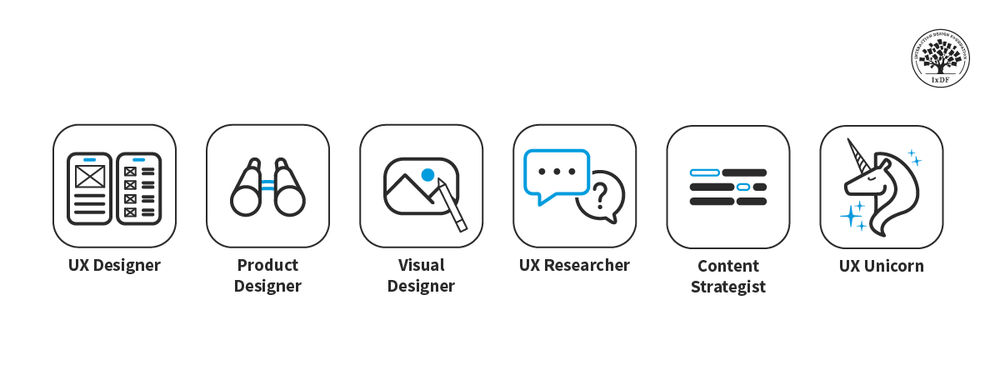

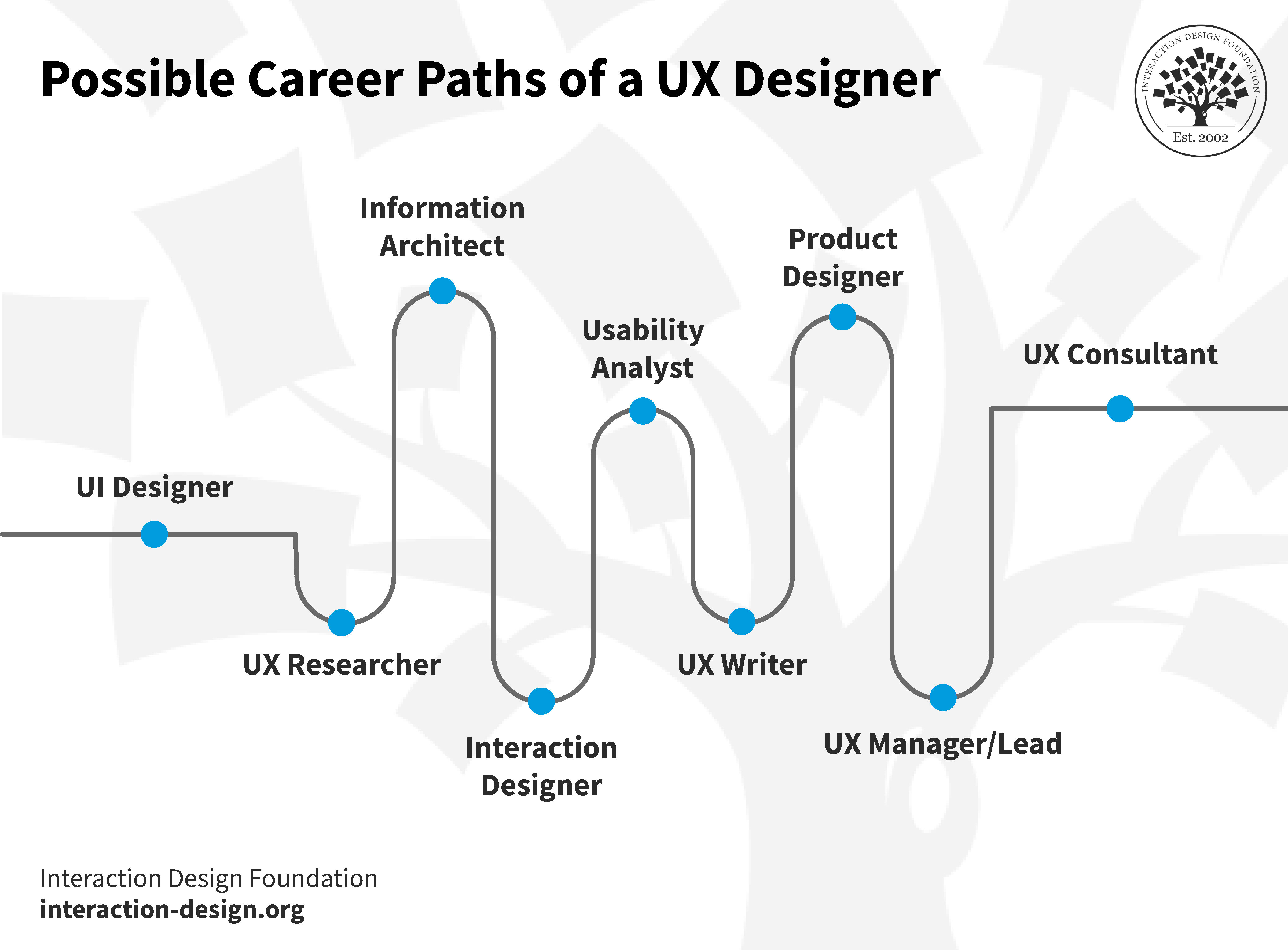

Possible Career Paths of a UX Designer

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

“Creativity”—the lifeblood and energy source that helps all types of professionals power their way through problems that seem even insurmountably tough, complex, or weird and wild. Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains how there’s quite a lot more at play, and here’s what it means to be creative.

Look at potential career paths:

UI Designer: It’s a job title that calls for strong skills in graphic design, and that’s because the UI designer is the one who’s got to make the “screen stuff” in the form of visually appealing design elements that bridge the worlds between technology and users. These designers do this when they create digital interactions that are smooth, efficient, and enjoyable—or, ideally, delightful.

UX Researcher: The province of user experience research is to get to the bottom of things and understand user behaviors, needs, and motivations, and their work finds them conducting surveys, interviews, and usability tests—all parts that are well and truly critical in the making of user-centered designs.

Information Architect: They’re the specialists who know how to not just structure digital products but organize them, too, so easy navigation and a seamless user experience are the fruit of their efforts. What goes into this worthwhile role include staples like making user flows, site maps, and content inventories.

Interaction Designer: True to the name, these are the designers who have a focus on the interactive aspects of what their brands ultimately release—elements like buttons, animations, and transitions—and the ultimate goal is to create engaging interfaces.

Usability Analyst: These analysts take it upon themselves to evaluate products—you know, websites, apps and those exciting sorts of things—to see how easy they are to use, and they’ll find issues and come up with solutions to give the user experience a palpable boost in places, often crucial ones.

UX Writer: They’re the ones who handle everything text-wise, as in, creating clear and concise copy for digital products, and that’s who makes user-friendly texts that really complement the UX design.

Watch Torrey Podmakersky, Author, Speaker, and UX Writer, discuss the pathway to becoming a UX writer.

Product Designer: A broader, more generic role, this one really calls for decision-making at a more strategic level, and overseeing the entire design process of a product is the name of the game with this role. Product designers might need to get a deeper understanding of all aspects of design and—sometimes—even front-end development, too.

UX Manager/Lead: Heading up UX teams and projects, the manager—or lead—is who focuses on strategy, team management, and making sure that project goals come into line with user needs.

UX Consultant: They work independently or with consulting firms, and they’re the people who provide expert advice and solutions to companies on their UX strategies and where to take them.

These roles really show the versatility of a career in UX design, and each one of them calls for a blend of technical skills, creativity, and an understanding of user psychology. The right path for you is really going to be up to you—as in, it’ll be down to your individual interests and skills.

The Power of Networking as a UX Designer

Networking—as in, with fellow design professionals—is a powerful plus, if not something that’s absolutely essential for broadening your knowledge base, staying updated in a field that evolves so rapidly, getting mentorship, and some more reasons, like these:

Job opportunities: Often, companies fill UX design jobs through referrals, and it’s networking that really raises your chances of learning about—as well as securing—these opportunities.

Feedback and collaboration: Share your work with peers and it’ll lead to constructive feedback—and that’s a potentially powerful plus to give your design skills a great lift.

Build confidence: Regular interaction with seasoned professionals gives your confidence a great boost—that’s something powerful when you’re on the look-out for UX design jobs, for example.

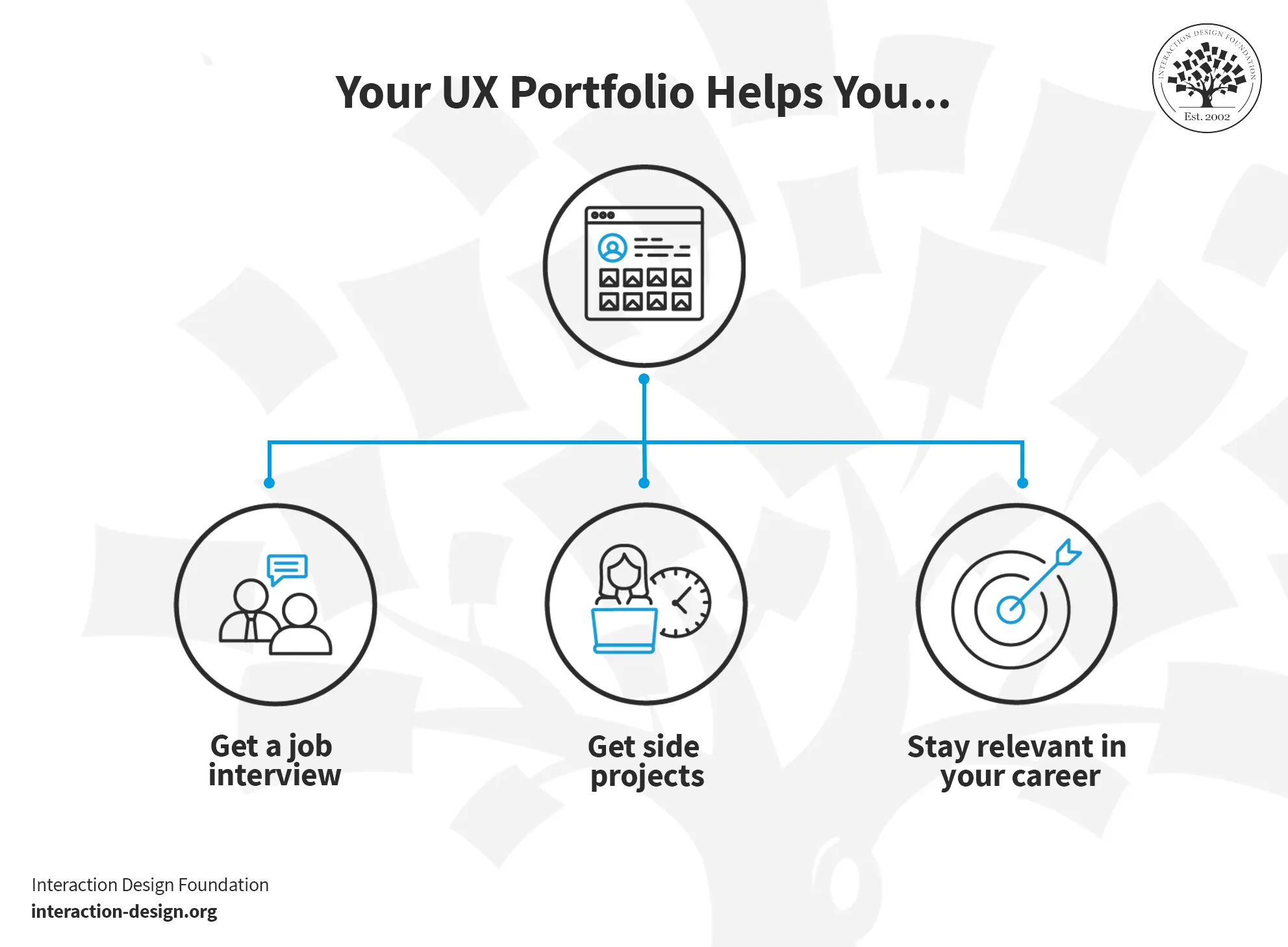

Much like in many other professions, networking is something that’s so important it can’t be overstated as a thing to do. In UX design, though, there’s an element to the calculus of propelling yourself as a professional, and networking works well when you’ve got your work to showcase as a kind of shop front—and, for that, you’re going to need to get a really good portfolio out there to speak for what you can do.

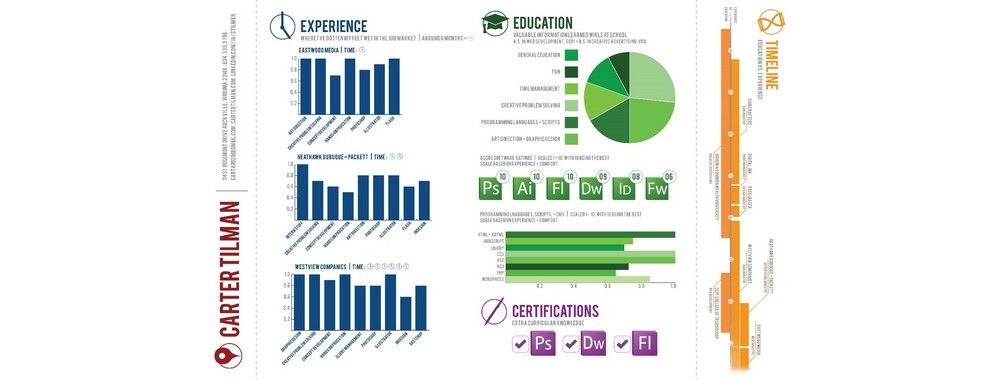

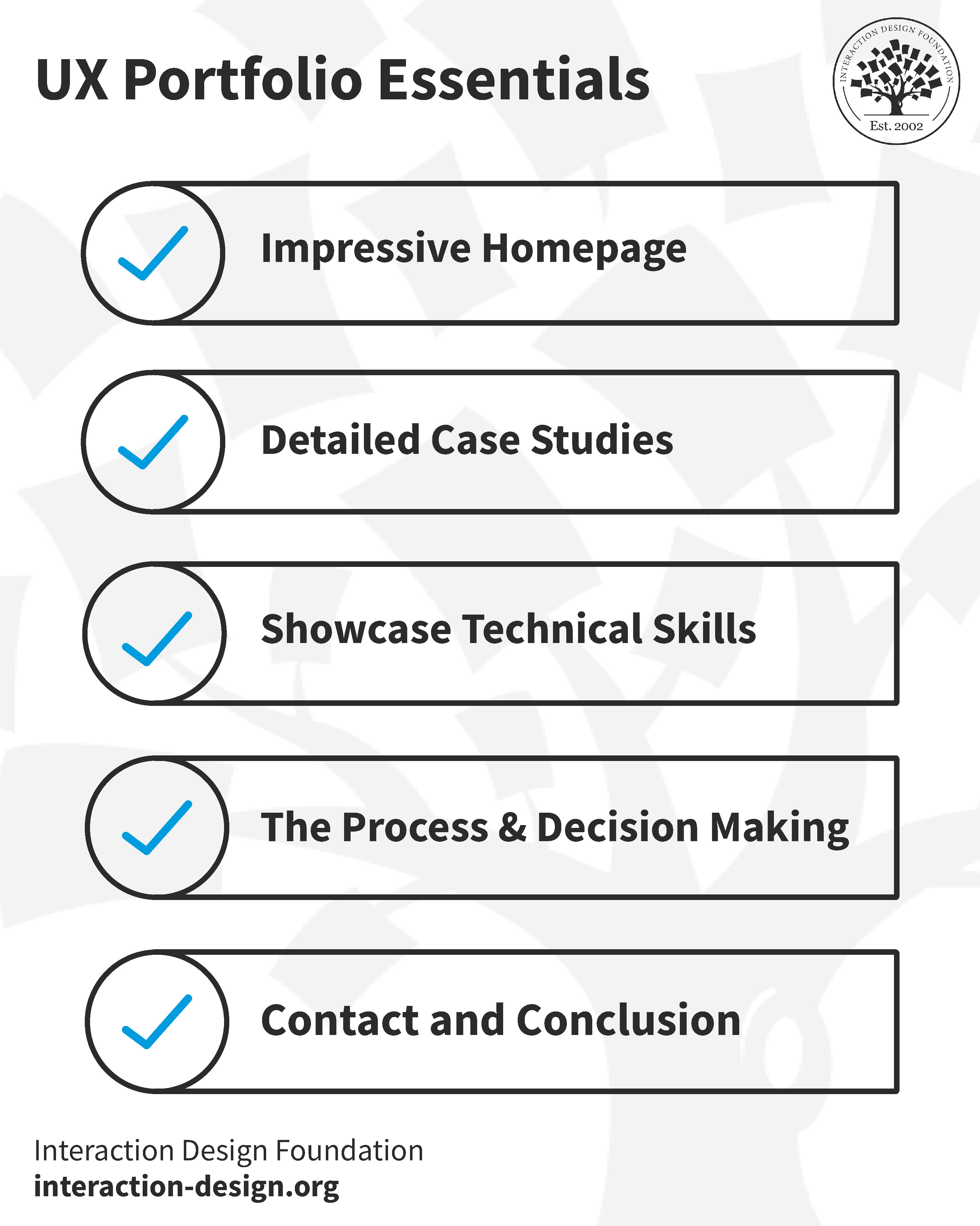

How Do You Create a Better UX Design Portfolio?

Now we come to what may be the most important design a designer can produce, release, and be proud to call their own: yes, that’s the value of a UX design portfolio. It’s where your career’s visual story meets your “shop window” to the world and sells your skills and experience to potential clients and employers, ideally with all the appealing verve and exceptional usability to act as a kind of sample of what a design from you is going to be like for them. It’s got to highlight your best work, filled with the choicest pick of projects that show how versatile you are, and—underscoring that—show the mind behind the scenes and how it works and works things out, as it may well be the mind they decide to hire for their own projects.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Watch as Morgane Peng, Managing Director at Societe Generale CIB explains important points about UX portfolios:

1. Impressive Homepage

Highlight key projects here; each project’s got to tell a story—so, to start, focus on the problem, your design process, and the solution too, and it’ll demonstrate your user experience expertise nicely.

2. Detailed Case Studies

These are a must, as they’re the evidence that covers your role, the challenges you faced, and how you applied those vital UI design principles. It’s in these where you showcase your skills in visual design, information architecture, and usability, and it’s wise to include those precious visuals like wireframes or prototypes.

3. Showcase Technical Skills

Show how well you do visual design, and put in the projects that really showcase what you can do and your prowess with tools like Illustrator, as it can highlight your graphic design skills and more.

UX leader at Google One, Stephen Gay, shows how important good storytelling is in portfolios.

4. The Process and Decision-Making

Your portfolio isn’t just about the final product; more importantly—it’s about your journey, too, so put your thought process and decision-making in there.

In this video, Stephen Gay shares his number-one tip on what to include in a portfolio.

5. Contact and Conclusion

End with a clear, concise contact page, and do make it easy for potential employers or clients to actually reach you.

Your conclusion should be something that compels the employer to take action—as in, to select you for an interview. It's an important thing, too, to mention your availability for interviews or to start work, and be sure you keep it concise and compelling—remember, it’s like your shop front.

Your UX portfolio helps you get a job interview or side projects and stay relevant in your career.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

The Take Away

Every design project poses a unique set of challenges that, as a UX designer, you’ve got to prepare for. While the tangible deliverables that UX designers create are easy to grasp, indeed, a better mindset is what makes UX designers successful in that they:

Continuously practice the craft of UX to deliver increasingly better artifacts.

Communicate these artifacts so that the rest of the team understands them easily, trusts them, gets behind them, and then acts on them.

Embrace complex and wicked problems and realize there’ll never be a straightforward answer—ever.

Think flexibly, approach problems from different perspectives, and be ultra-open to solutions.

Most importantly of all, keep learning—knowledge is power and you’re in a living career and an ongoing process, to be—and keep being—the best UX designer you can be.

References and Where To Learn More

Glassdoor’s research on the expected pay of UX designers across companies

Take a course from IxDF to learn UX design and grow your career

Read the Forbes article on How To Bring Your Products To Life With Good UX Design

Images

© Christian Briggs and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0