Getting great interview results requires careful preparation. You need to be clear about the purpose of your research, decide whom to recruit, do all the practical preparations, and—finally—you need to design a great interview guide detailing the questions you want to ask. Here, you will learn how to prepare for user interviews and how to ensure that you ask the right questions, in the right order.

Preparing for an interview requires you to think through each step of the project: what you need to find out, whom you need to ask, where you will conduct the interview, how you will record the interview and what the best way is to ask questions in order to get a good flow. Here, we will start by discussing the practical preparations; then we will discuss how you decide how many participants you need. Finally, we will elaborate on how to prepare an interview guide with relevant questions.

Interview Preparation

It’s important that you start your interview project with a clear idea of the purpose of your research. That is, why you want to do the research and what you want to find out. In the same sense as you can’t pick a tool before knowing if you need to hammer a nail, turn a screw or drill a hole, you shouldn’t choose your research method before you know what you want to find out. In a qualitative study such as semi-structured interviews, it’s perfectly fine for your overall research question to be broad and exploratory—e.g., “We want to find out how people use video streaming in their everyday lives and how they feel about the services they use.” When defining the purpose of your research, remember to involve the most important stakeholders in the design project you are working on. It’s vital that you ensure that you have stakeholder buy-in for your interview project, and a good way to do that is to make sure that you all agree on what you will get out of the research and the effort it will require.

In relation to more practical considerations, you need to think about what user group(s) you want to involve, how you are going to recruit them, where the interviews should take place, and how you will record data from the interview.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

Here, professor of Human-Computer Interaction at University College London and expert in qualitative user studies Ann Blandford talks about different ways in which the interview setting affects the atmosphere for the interview.

As you answer these questions, you will find yourself with a list of practical tasks you need to perform before you do the interviews—e.g., arrange travel, book a suitable location, recruit participants, and decide on a recording device. Many researchers just use their smartphones for audio or video recording. That’s fine, but remember to ensure you have enough storage space and battery power to record the duration of the interview.

Recruiting Participants

There are no set rules as to how many participants you should include in an interview project—it depends on what you are studying, how many user groups you want to involve, and how many resources you have for your project. The grounded theory methodology recommends that you don’t decide beforehand how many participants you need, but let the results guide you as to when you should stop. In that case, you start out interviewing (e.g.) five participants. You then look at what your participants have told you so far in order to see how similar the participants’ answers are and how many new topics are appearing with each new interview. If you notice by participant 5 that you didn’t get much information you didn’t already have from the previous interviews, you probably don’t need to recruit any more participants. However, if you see that participants give very different answers and new topics continue to arise, you should recruit more participants, and—ideally—you should continue the process until you reach a point where you have information saturation. Similarly, some of the results might indicate that you need to include a user group that you had not previously considered and you have to modify your recruitment criteria. Let’s say you have interviewed one female and four male participants and you discover that the female participant gives completely different information than the male participants. In this situation, you would probably want to recruit more female participants so as to ensure that you explore both perspectives. In most interview projects, more practical considerations such as time and resource constraints also play a big role in deciding how many participants you end up recruiting. That means that you often have to interview fewer participants than you would have ideally preferred. In that case, you need to narrow down the focus of your project and refrain from following up on all potentially interesting themes in your research. This may seem hard when you’re on the cusp of discovering some fascinating areas you hadn’t first noticed, but practicability is essential—you need to home in on a localized area and take things from there.

© Clker-Free-Vector-Images, CC0

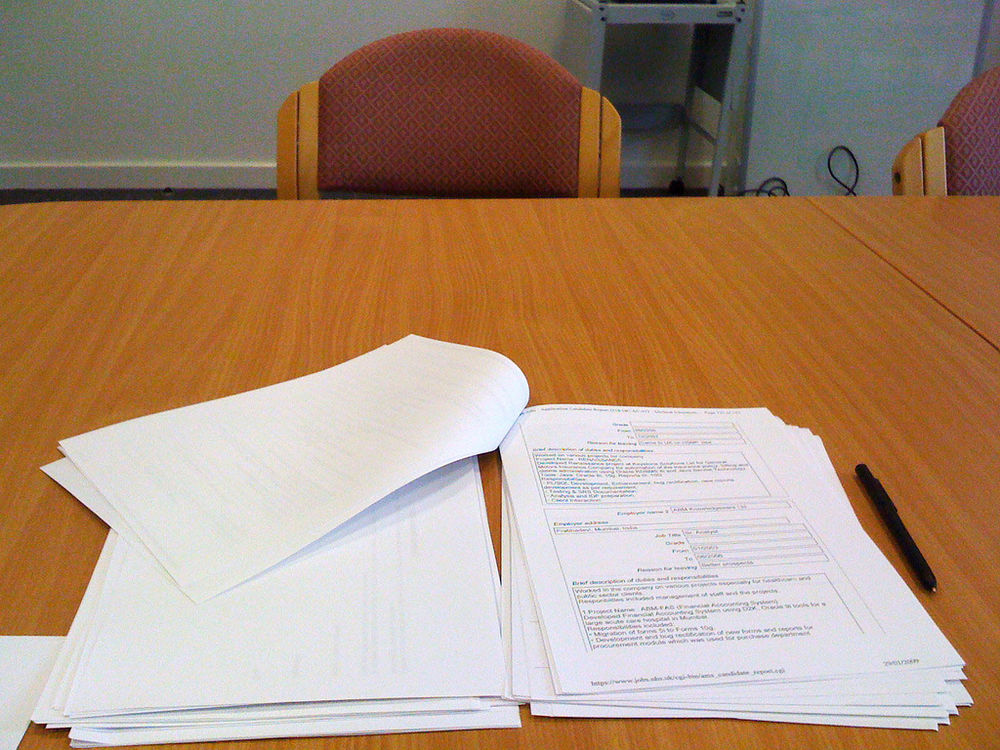

Aside from having a clear idea of the purpose of your research and ensuring that you make all the practical arrangements, writing your interview guide is the most important preparation for the interview itself.

The Interview Guide

The interview guide is a document in which you formulate the questions you want to ask your participants, in the order that you expect to ask them. In other words, your interview guide is your script for the interview. When you write your interview guide, think about what you want to know and then formulate concrete questions based on that. Your interview guide is closely tied to the purpose of your research, and it ensures that you can deliver the insights you promised to deliver. It’s a good idea to test the interview guide—try asking yourself or somebody else the questions, and then determine whether or not you can deliver the insights you promised based on the answers you get. Your interview guide is also a good tool to help you think through the best way of asking questions before the interviews. During the interviews, the guide serves as a reminder of the themes and questions you want to make sure you cover. Although you write down the questions as you would ask them, in the order you think makes the most sense, you don’t necessarily end up following that order during the interview itself. In a semi-structured interview, you have a carefully laid plan and you are responsible for the overall structure of the conversation, but you also let the flow of the conversation decide how and when to ask questions. In other words, you have to safeguard the interview process from being derailed by off-topic points and the like, at the same time allowing a natural style so that the interview can carry itself. This takes a good ear and a sharp eye (and memory) for detail.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

In this video, Ann Blandford talks about the best way to order questions in a semi-structured interview session and how much you should stick to your theme when you do an interview.

You can download our overview of how to structure a user interview here:

How to ask questions

“The best scientists and explorers have the attributes of kids! They ask questions and have a sense of wonder. They have curiosity.”

—Sylvia Earle, Marine biologist, explorer, and author

When you conduct an interview, you will want to make sure that you ask questions in such a way that gives you the information you are looking for and which makes it easy for participants to answer. When you ask questions, they should be relatively brief and easy to understand. Try to speak in a vocabulary that is familiar to your participant. If you think of the video streaming example from earlier, it’s not a good idea to ask your participants directly how video streaming fits into their everyday lives. You must turn your overall research question into more concrete questions that will then answer your overall question. Instead, you could ask questions like “Can you tell me about the last time you used video streaming?” or “How have your movie/TV-watching habits changed since you started using video streaming services?”. In their book InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, psychology researchers Steinar Kvale and Svend Brinkmann state that you should ask the concrete “how” and “what” questions before you ask the more abstract “why” questions. Even if you are mostly interested in why people are doing something, it can be difficult for them to answer. “How…?” and “What…?” prompt direct responses from an interviewee, but “Why…?” involves getting behind the scenes and looking at factors driving a person. A “why” question can also sound rhetorical in some cases—so, the person asked may feel a little defensive in addition to feeling some confusion. Given that, sometimes you’re better off finding answers by deducing what your interviewees are doing in concrete situations.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

A good way to help people recollect how they normally do something is to ask for concrete examples. In this video, you will see Ann Blandford explain how to use concrete examples and the critical incidents technique in interviews.

You can download our template explaining how to use concrete examples and critical incidents in interviews here:

You can also download an example of an interview guide here:

The Take Away

Before you can conduct user interviews, you need to make practical preparations and design a good interview guide. When you design your interview guide, think about what questions are most suited for the beginning, middle, and end of your interviews—but be prepared to change the order of questions to suit the flow of the conversation during the interview. When you ask questions, be as concrete as possible and ask them in a way that makes it as easy as possible for people to recollect. An effective way to help people recollect past experiences is to use the critical incidents technique.

References & Where to Learn More

Ann Blandford, Dominic Furniss and Stephann Makri, Qualitative HCI Research: Going Behind the Scenes, Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2016

Steinar Kvale and Svend Brinkmann, InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. SAGE Publications, 2009

You can read more about why it’s a great idea to ask lots of open-ended questions in this article from the Nielsen Norman Group: Open-Ended vs. Closed-Ended Questions in User Research

Image

Hero Image: © SteveRaubenstine, CC0