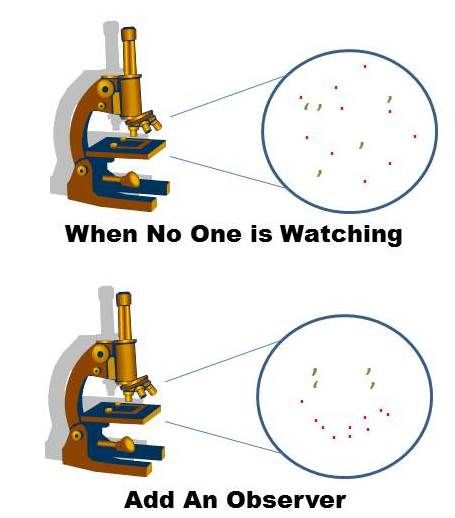

If you’re going to observe your users in your UX research, and you probably should, you need to know that the act of observation can have an impact on individual behaviour. The Hawthorne effect is common in research and by understanding it, you can (to some extent at least) moderate its effect on your research.

Imagine that you work in a factory for a second. One day, your boss comes to you and says that they want to do a little experiment on productivity. They’re going to increase the lighting in your workplace and see whether that makes you more productive. Then you go to the pub after work and sit with a couple of friends. You tell the story of your boss’s experiment and they look at you a little strangely and then tell you their stories.

Author/Copyright holder: Kheel Center. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY 2.0

Their bosses are also looking at lighting and its effect on productivity and one of your friends is having the lighting decreased in their environment. The other friend has been told they are a control and that their lighting will be left at the same level.

The experiment is going to take place next week and you all agree to meet back in the pub to discuss the results at the end of the week. When you return, who do you think will report the greatest increase in productivity? (For the sake of this thought experiment – you can assume you all do similar jobs and that lighting conditions are identical prior to the experiment).

The Peculiar Result

It doesn’t matter whether the lighting is increased, decreased or left alone. You all report similar levels of increased productivity.

But when you return to the pub a week after the experiment has ended – you find that all of your levels of productivity have returned to normal.

The Hawthorne Effect

In 1958, the term “Hawthorne Effect” was minted by Henry A. Landsberger. He was investigating research which had been carried out between 1924 and 1932 in the Hawthorne Works (which was a factory based near Chicago).

They found that whenever they manipulated the lighting to see what effect it had on productivity – productivity went up. In fact, it went up even when the changes were imperceptible to the human eye (the equivalent of not making a change at all).

Yet, once they’d finished making changes; productivity quickly returned to normal.

They also tested other factors regarding productivity; they focused on the neatness and cleanliness of work stations, then on keeping floors free of any possible obstacles and even moved workspaces around the environment. All of the results showed something similar; a change was made, an improvement arose in productivity, shortly after that – productivity slumped back to normal.

Author/Copyright holder: BAKOKO. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-ND 2.0

What Landsberger deduced was that the studies had played a part in the increase of productivity. When the observers looked for productivity improvements they found them. When they stopped looking, those improvements disappeared.

The Hawthorne Effect is, in essence, a phenomenon of research. By focusing a researcher’s attention on something; the subject is likely to strive to deliver the expectation of that research.

The Controversy

It is worth noting that not everyone agrees with Landsberger’s conclusions. Other researchers feel that the management climate of the Hawthorne Works and the specific types of interaction that researchers had with workers would have played their part in this outcome.

Many argue that a simple manipulation check (where manipulations are delivered at random to act as a control for the manipulation used by the researcher to insure that the manipulation had no bearing on the results) will eliminate the Hawthorne Effect.

However, there is no doubt that the Hawthorne Effect is now well-established in multiple studies and that no matter how much controversy it attracts – it is likely that the action of observing someone in research affects the way that they behave.

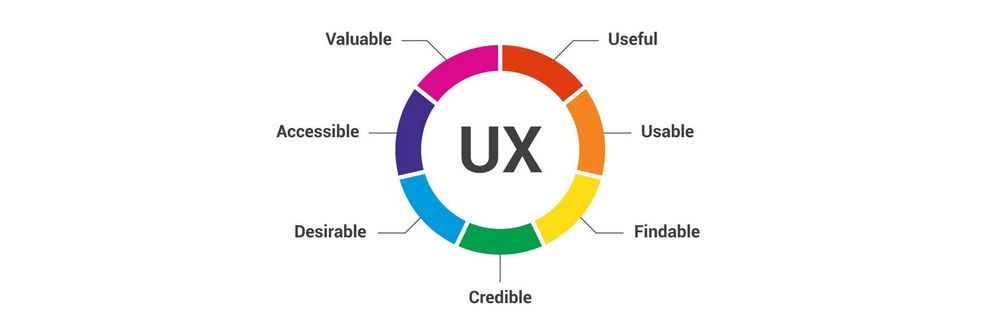

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown. Copyright terms and licence: Unknown.

Interestingly, a very common place for the Hawthorne Effect to be found is in corporate training. The action of training can often provide a temporary boost to productivity and skill which disappears in the longer term.

Why Does This Matter for UX Design?

It matters because we need to think about our research in context. If a short-term study designed to find an outcome invokes the Hawthorne Effect – it is likely that our study will give us the results that we expect even if they don’t reflect the user’s reality on a day-to-day basis.

There are two actions we can take to try and minimize this. The first is to address the issue of expectation in research. If we can keep the participants unaware of our expectations (and the best way to do this is to use research to try and test a hypothesis as opposed to using it to prove an expectation) then we can reduce the likelihood that they will produce the results we expect to see.

The second is to account for the Hawthorne Effect. If you are going to have to indicate an expectation from your research; then the research needs a longer “follow up” period. Where you can examine whether a behaviour (or change in product) is sustained beyond the research or whether it only exists in a short-period during and following the research. If the former is the case – the Hawthorne Effect is irrelevant, if the latter – you may need to revisit the design of the product.

The Take Away

If you know that the act of observation may potentially influence the results of your research, which is what the Hawthorne Effect suggests, you can take steps to eliminate the impact of the Hawthorne Effect. This gives you a greater chance of delivering an end product that satisfies the user and delivers a great user experience.

References

You can better understand manipulation checks by delving into their development here.

The Economist supplies some interesting analysis of why the Hawthorne Effect exists and further reading on the original studies here.

A recent paper confirms the existence of the Hawthorne Effect but fails to demonstrate the underlying reasons for it. See here.