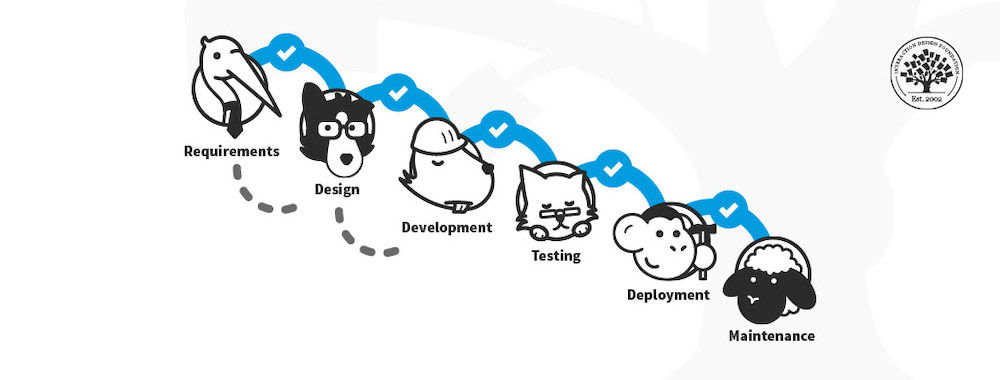

The words “design” and “designer” are quite common in society, but they are not used very precisely. Most of us have heard of designer clothes or accessories, but apart from the greater expense what does that mean? The basic definition of the word “design” is simply to plan something in advance. So, almost all human artifacts are designed to a certain extent. Designer jeans or handbags are just the product of a designer or design studio with a sought-after reputation.

A Collection of Designer Bags

A Collection of Designer Bags© Kai Gabriel and Laura Chouette, Unsplash, CC BY-SA 3.0

But the term “design” is so ubiquitous that we almost take it for granted. Nevertheless, while you might consider building a garden shed or chicken coop without much in the way of formal design, you would expect to see some detailed plans for a house or hospital that was being built.

There are similar parallels in computer-based systems. If you were building a simple app or web site, similar to many that you’ve produced already, you may decide to jump right in without much in the way of formal design. And to a certain extent, the way that many software projects are conducted encourages this. For example, in Agile approaches, “big up-front design” is discouraged and the focus is on delivering “working” code. Unfortunately, this philosophy has led to “design” per se becoming undervalued. And while Agile approaches can produce usable systems, this can only happen when we’ve thought in advance about what we’re trying to achieve and for whom. The “working” code we produce needs to work for its users in real situations, real “contexts of use”.

Alan Dix has more to say about the process of design and the importance of considering users’ needs…

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

Image

© Eduardo Ferreira and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0