Have you ever come across a problem so complex that you struggled to know where to start? Then you might have stumbled upon a wicked problem. While wicked problems may not have a definite solution, there are certainly things you can do to mitigate any negative effects. When you learn how to tackle wicked problems, you learn how to improve the world and the lives of the people who live in it. Here, you’ll learn the ten characteristics of a wicked problem and five steps to tackle wicked problems.

Table of contents

- What Is a Wicked Problem?

- What is the Difference between Puzzles, Problems and Wicked Problems?

- Which Wicked Problems Do We Need to Deal with?

- 10 Characteristics of a Wicked Problem

- From Wicked Problems to Complex Socio-Technical Systems

- Wicked Problems and Design Thinking

- A Combination of Systems Thinking and Agile Methodology Can Help You Tackle Wicked Problems

- 5 Ways to Apply Systems Thinking and Agile Methodology in Your Work

- The Take Away

- References & Where To Learn More

- Images

What Is a Wicked Problem?

A wicked problem is a social or cultural problem that’s difficult or impossible to solve because of its complex and interconnected nature. Wicked problems lack clarity in both their aims and solutions, and are subject to real-world constraints which hinder risk-free attempts to find a solution.

Classic examples of wicked problems are these:

Poverty

Climate change

Education

Homelessness

Sustainability

What is the Difference between Puzzles, Problems and Wicked Problems?

Let’s create an overview by first looking into the difference between a puzzle and a problem, and then afterwards we’ll examine wicked problems.

Which Wicked Problems Do We Need to Deal with?

Many of the design problems we face are wicked problems, where clarifying the problem is often as big a task as solving it… or perhaps even bigger. Wicked problems are problems with many interdependent factors making them seem impossible to solve as there is no definitive formula for a wicked problem.

A wicked problem is often a social or cultural problem. For example, how would you try to solve global issues such as poverty… or education? What about climate change, and access to clean drinking water? It’s hard to know where to begin, right? That’s because they’re all wicked problems.

What makes them even worse is the way they’re intertwined with one another. If you try to address an element of one problem, you’ll likely cause unexpected consequences in another. No wonder they’re wicked! It’s clear to see that standard problem-solving techniques just aren’t going to cut it when you’ve got a wicked problem on your hands.

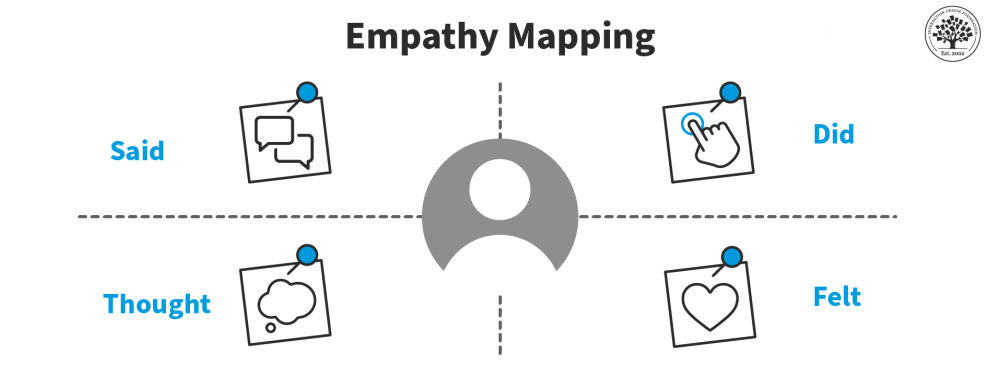

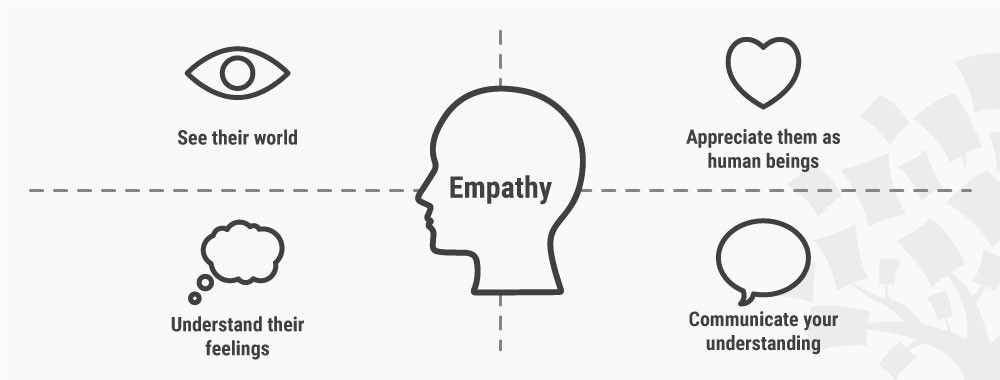

You’ll need to gain a much deeper insight into the people involved and learn how to reframe the problem entirely if you want to have any sort of chance at coming up with a valuable solution.

10 Characteristics of a Wicked Problem

As you can see, we need to dig deeper to understand the essence of wicked problems. Horst W.J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber, professors of design and urban planning at the University of California at Berkeley, first coined the term wicked problem in “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning” (1973). In the paper, they detail ten important characteristics that describe a wicked problem:

There is no definitive formula for a wicked problem.

Wicked problems have no stopping rule—there’s no way to know whether your solution is final.

Solutions to wicked problems are not true or false (right or wrong); they can only be good or bad.

You cannot immediately test a solution to a wicked problem.

Every solution to a wicked problem is a “one-shot operation” because there is no opportunity to learn by trial and error—every attempt counts significantly.

Wicked problems do not have a set number of potential solutions.

Every wicked problem is essentially unique.

Every wicked problem can be considered a symptom of another problem.

There is always more than one explanation for a wicked problem because the explanations vary greatly depending on the individual’s perspective.

The planner/designer has no right to be wrong and must be fully responsible for their actions.

We still face the classic wicked problems in today’s world; however, there are further examples we now have to consider. Business strategy, for example, is now often classed as a wicked problem because strategy-related issues normally meet at least five of the characteristics listed above.

From Wicked Problems to Complex Socio-Technical Systems

The rapid technological advancement of the 21st century has, in many ways, mutated wicked problems. In today’s hyperconnected world, it is difficult to look at problems in isolation.

Let’s look at sustainability, for example. Recycling is often considered as one of the solutions to achieve sustainability. Don Norman, in his two-part essay for FastCompany, examined recycling and remarked: “I am an expert on complex design systems. Even I can’t figure out recycling.”

He describes in detail how difficult it is for people to send their household waste to get recycled. There are different rules for different materials—paper, plastics, glass, metals. And within a category, say, plastic, there are different rules for different types of plastic in different places. Not all plastics can be recycled. Those that can be recycled, demand specialized equipment and processes that are not universally available.

“Recycling is a poor solution to the wrong problem.”

— Don Norman

The complexity of recycling is a problem. But why do we need to recycle at all?

It's because most of the products we use in our lives are made from non-reusable materials. Consider smartphones—most, if not all, have batteries that cannot be separated from the device. If your battery no longer functions as intended, you must replace it with a new phone.

What if the iPhone had a removable battery, which could be fixed or replaced so that you didn’t have to throw out the entire phone, if (when) the battery died? What if phones weren’t built to crack or become obsolete within a short time?

What if companies considered alternate materials to manufacture phones, or government legislation made it mandatory for companies to take back all their material, and put them back into the manufacturing process? The piles of garbage on the planet are a part of what Don Norman calls complex socio-technical systems. Let’s hear more on this from Don Norman:

Wicked problems, or as Don Norman prefers to call them, complex socio-technical systems, are not isolated. They are intertwined in existing systems—manufacturing systems and economic systems, political, social and cultural systems, technological and legal systems. And each of those systems is connected with the other.

So, how can you start to tackle wicked problems, both old and new? Let’s look at how design thinking—more specifically, systems thinking and agile methodology—can help us start to untangle the web of a complex socio-technical system.

Wicked Problems and Design Thinking

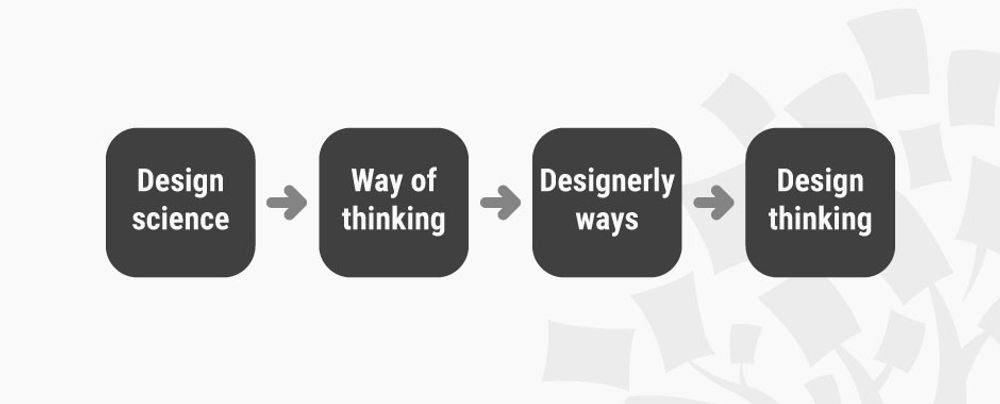

The design theorist and academic Richard Buchanan connected design thinking to the innovation necessary to begin tackling wicked problems. Originally used in the context of social planning, the term “wicked problems” had been popularized in the paper “Wicked Problems in Design Thinking” (1992) by Buchanan. Various thought leaders following Buchanan continued on to suggest we utilize systems thinking when faced with complex design problems, but what does that look like in practice for a designer tackling a wicked problem and how can we integrate it with a collaborative agile methodology?

A Combination of Systems Thinking and Agile Methodology Can Help You Tackle Wicked Problems

Design thinkers proceeded to highlight how we utilize systems thinking when faced with complex design problems.

Systems thinking is the process of understanding how components of a system influence each other as well as other systems—and therefore it’s pretty much perfect for wicked problems!

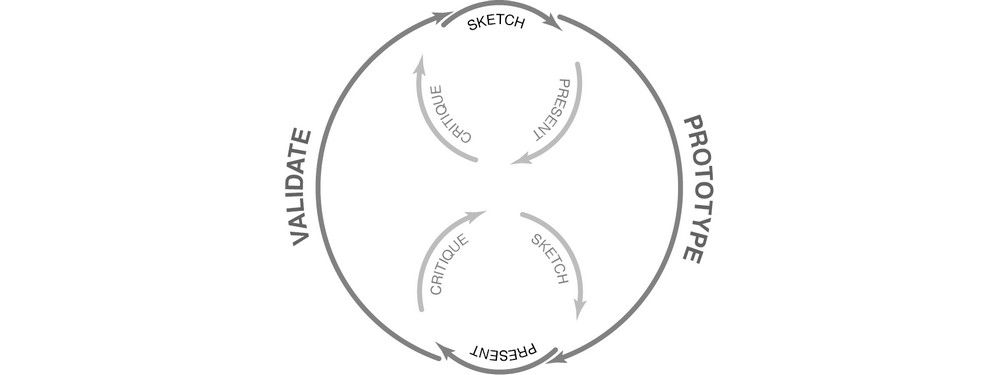

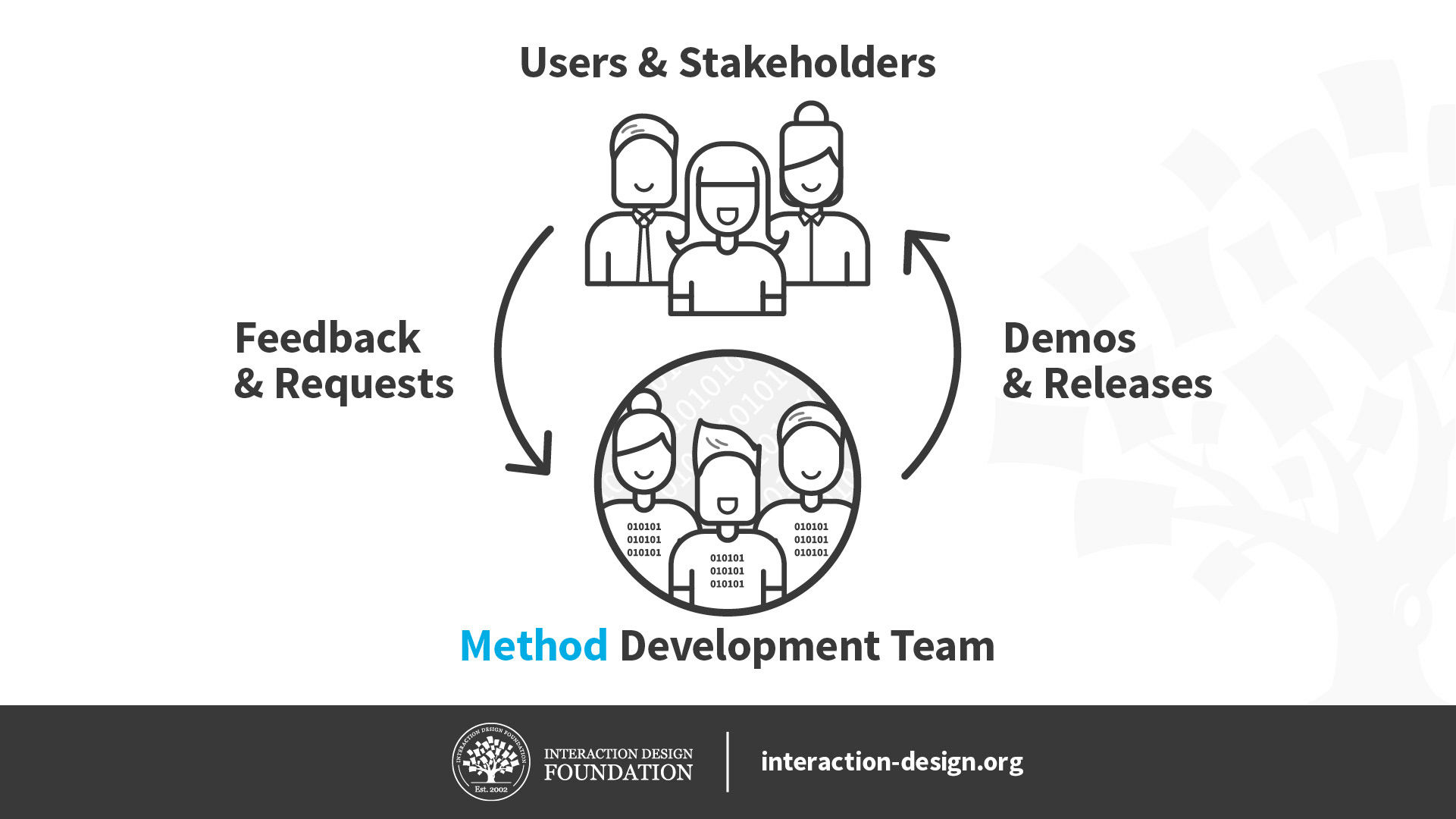

And it’s even better when combined with an agile methodology, an iterative approach to design and product development. Agile methodology helps to improve solutions through collaboration. This agile, collaborative environment breeds the ability to be efficient and effectively meet the stakeholders’ changing requirements.

Together, systems thinking and agile methodology lead us to a better solution at each iteration as they both evolve with the wicked problem.

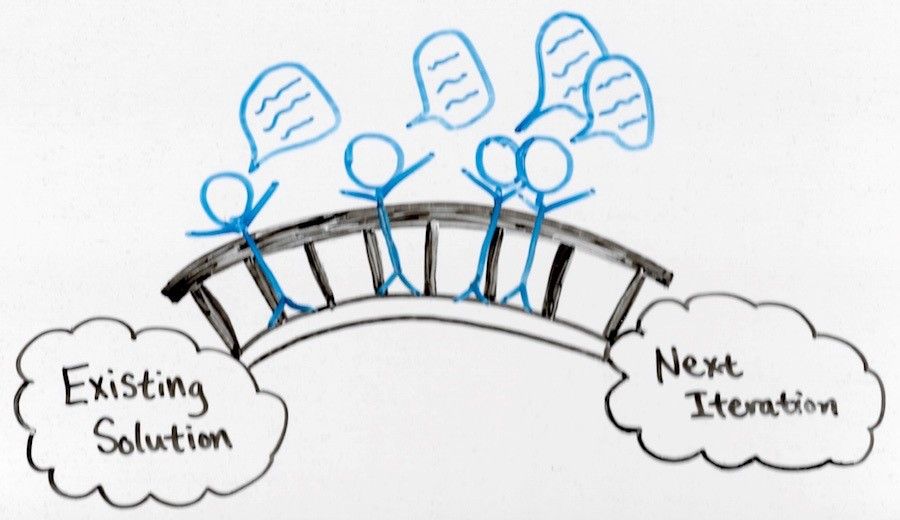

In an agile methodology, every iteration incorporates feedback from the previous release. This process can help you tackle wicked problems when it’s combined with systems thinking.

© Daniel Skrok and the Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

5 Ways to Apply Systems Thinking and Agile Methodology in Your Work

If you’ve been faced with a wicked problem in the past, you’ll have undoubtedly experienced frustration from not knowing where or how to begin. There’s no shame in that—issues which are difficult or nearly impossible to solve will do that to a person! The next time you and your team must tackle a wicked problem, you can use these five handy methods which are based on systems thinking and agile methodology:

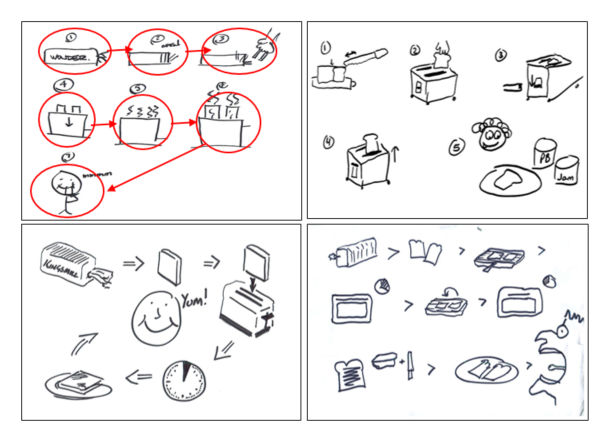

1. Break down information into nodes and links.

You can utilize systems thinking if you break the information down into nodes (chunks of information such as objects, people or concepts) and links (the connections and relationships between the nodes). This will make your private mental models (your representations of external reality) visible to the outside world and help you face wicked problems more effectively. Jay Wright Forrester, a pioneer in computer engineering and systems science, put it nicely when he said:

"The image of the world around us, which we carry in our head, is just a model. Nobody in his head imagines all the world, government or country. He has only selected concepts, and relationships between them, and uses those to represent the real system.”

—Jay Wright Forrester

In this illustration, the nodes are circled in red and the links are the red lines drawn between the nodes. All four illustrations are systems models that participants created from Tom Wujec’s workshops on collaborative visualization and systems thinking.

© Tom Wujec, CC BY 3.0

2. Visualize the information.

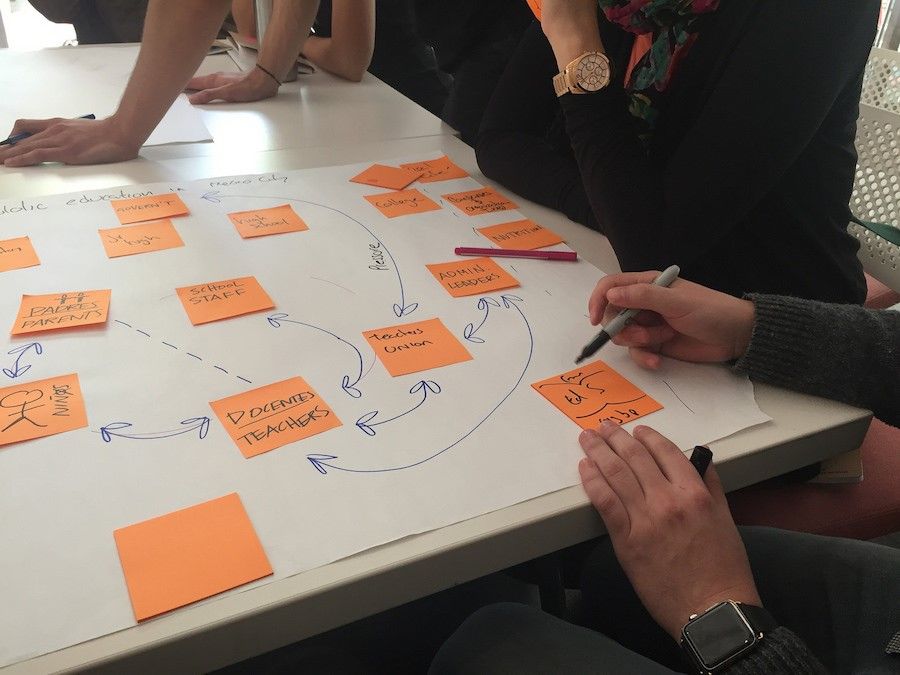

When you sketch out and place information into a physical space, it will help both you and your team take in and understand the systems at hand—as well as the relationships within and between them.

3. Collaborate and include stakeholders in the process.

Share your mental models to help other people build on your ideas, and vice versa. Your team can synthesize several points of view when you create physical drawings and group notes to produce different systems models.

4. Release solutions quickly to gather continuous feedback.

Feedback of success helps to solve problems which we don’t have one single obviously correct answer for. The more feedback you gather from your users and stakeholders, the more guidance you’ll have to get to the next step.

5. Carry out multiple iterations.

You and your team have the chance to utilize feedback at each iteration. The more iterations you do, the more likely you’ll determine what changes are needed to further improve the solution to your wicked problem.

You’ll build a bridge between the existing solution and the next iteration when you combine user and stakeholder feedback with your team’s thoughts and ideas.

© Un-School MX, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The Take Away

As designers, we have the responsibility to generate the best solution possible even when the wicked problem itself is indeterminate and the best solution does not yet exist. A combination of systems thinking and agile methodology can help us tackle these wicked problems. It encourages us to utilize these practices and share them with others so that we can, together, get to the next iteration of the design process.

When you start to tackle wicked problems, you can start to improve the world and the lives of the people who live in it. As a reminder, the five steps to do this are:

Break down information into nodes and links.

Visualize the information.

Collaborate and include stakeholders in the process.

Release solutions quickly and gather continuous feedback.

Carry out multiple iterations.

References & Where To Learn More

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy sciences, 4(2), 155-169.

Buchanan, Richard. (1992). Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Design Issues, Vol. 8, No. 2, (Spring, 1992), 5-21.

Ana de Almeida Kumlien & Paul Coughlan, Wicked problems and how to solve them, 2018.

John C. Camillus, Strategy as a Wicked Problem, 2006.

Amy C. Edmundson, Wicked-Problem Solvers, 2016.

John Kolko, Wicked Problems: Problems Worth Solving, 2012.

Stony Brook University, What’s a Wicked Problem?

Tom Wujec, TEDGlobal, Got a wicked problem? First, tell me how you make toast, 2013:

Images

Hero Image: © Diana Parkhouse, Unsplash License.