Design Briefs

What are Design Briefs?

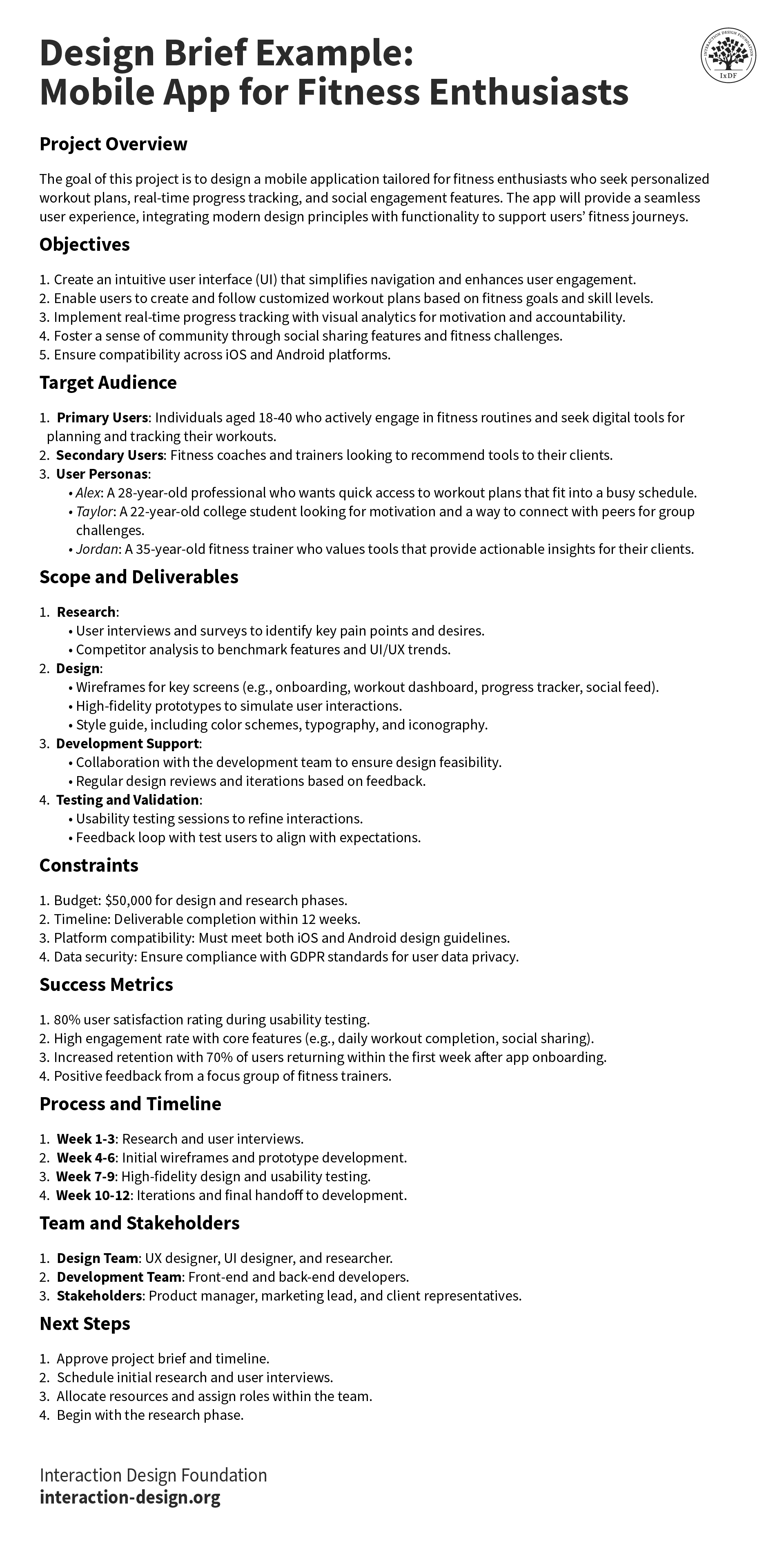

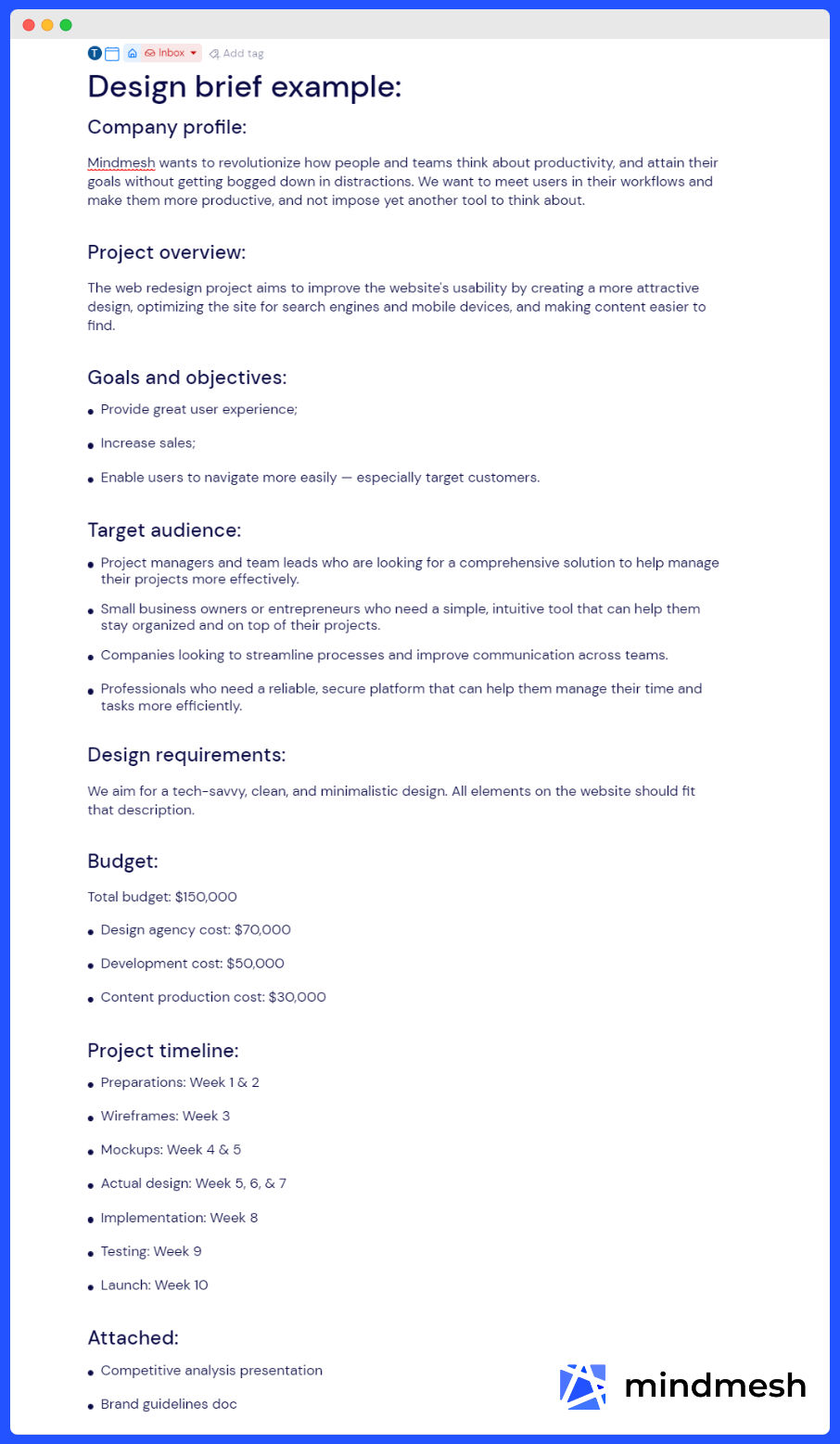

In user experience (UX), design briefs—also known as creative briefs—are comprehensive documents that outline a design project's objectives, target audience and constraints. Designers use them as roadmaps to understand user needs, pain points and business goals. They analyze briefs to create user personas, prototypes and more, to ensure the final product aligns with user expectations in successful digital products.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Why are UX Design Briefs Important?

Design briefs outline the scope, scale and core details of an upcoming design project; that applies to both UX design and user interface (UI) design. Briefs are powerful design tools since they guide the overall workflow—from conception to completion. They serve not just as a roadmap for designers but as a critical bridge between the client's aspirations and the designer's creativity also. This alignment ensures that every stroke of genius contributes to aesthetic appeal—plus, that it propels the project towards its strategic goals, from the earliest wireframes to the final deliverables.

Watch our video about wireframing to understand more about this design activity:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

One particularly vital function of a UX or UI design brief is that it provides a detailed description of the project—and that includes context, background and measurable objectives. This helps all team members understand the client's brand and the project's intended impact. A brief starts with the rationale behind the need for a new digital interactive design like a website or mobile app. This details how the proposed product or service is going to benefit the target audience as well as advance the brand's voice within the competitive landscape.

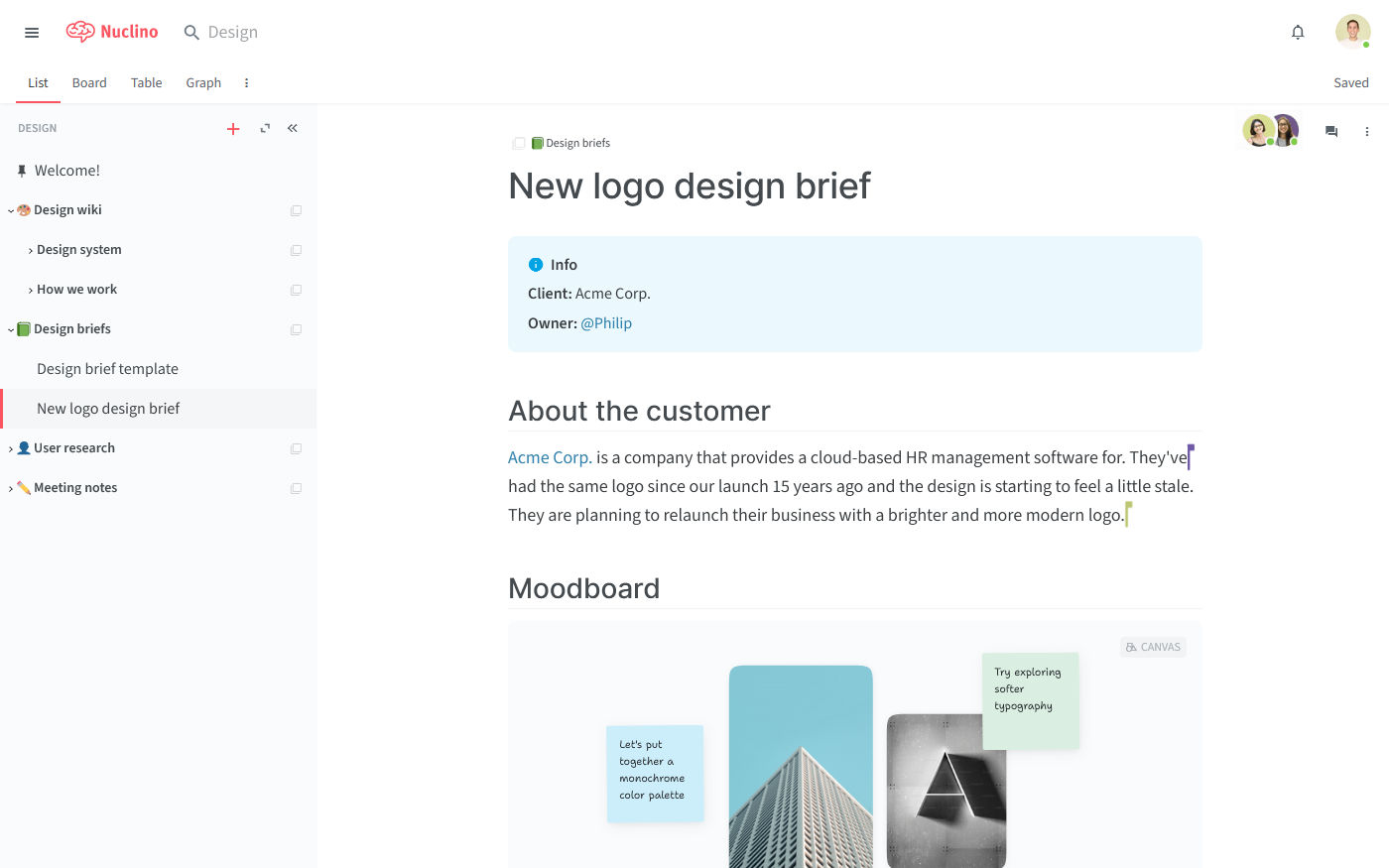

This is an example of a logo design brief, a core part of product or service branding.

© Nuclino, Fair Use

What are the Components of a Design Brief?

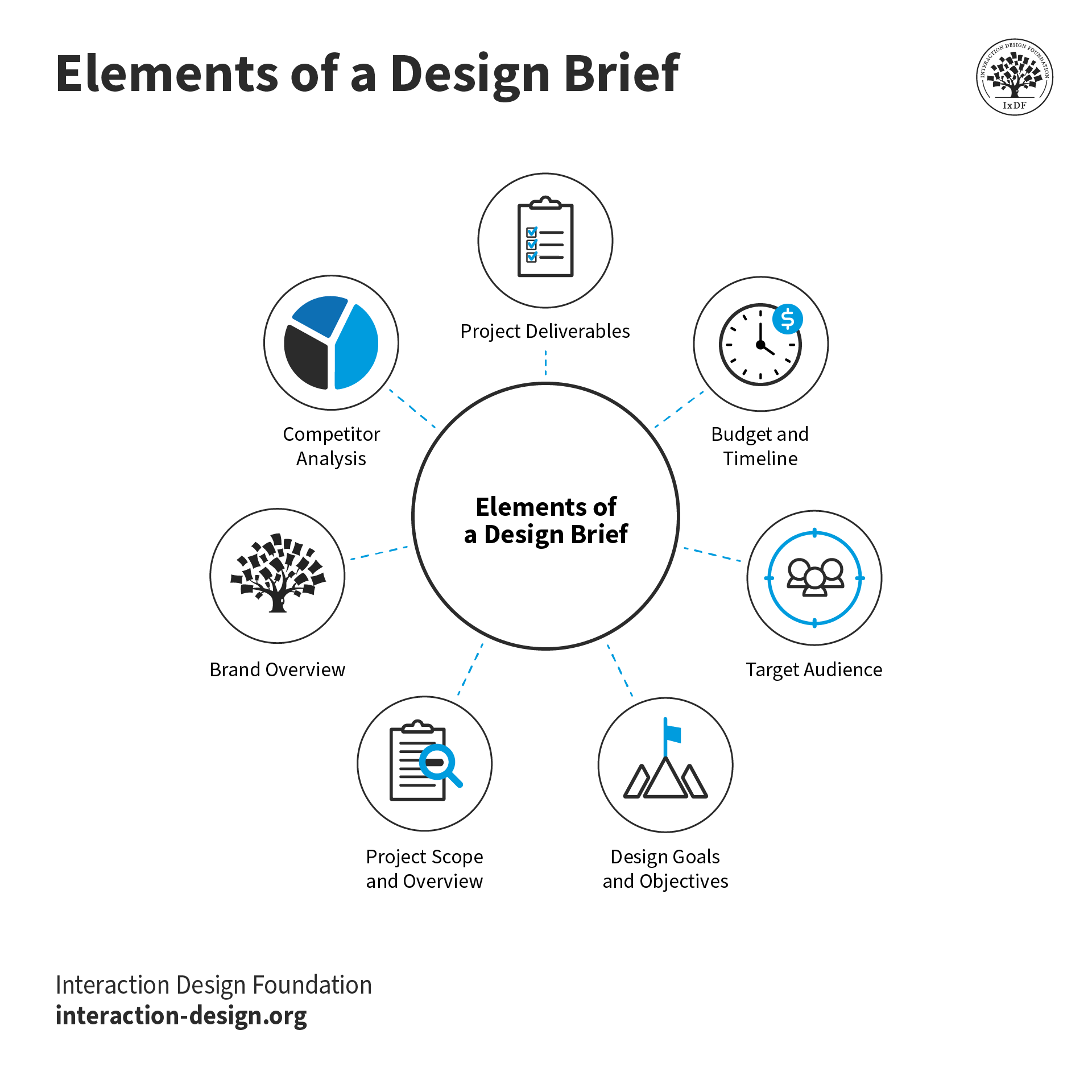

The effectiveness of a design brief lies in its components—which include these:

1. Brand and Project Overview

This section gives an overview of the client's business and the project. It offers as much context as it can to make sure everyone's on the same page.

2. Design Requirements and Deliverables

A brief specifies the needed design elements—such as layout, colors, images and fonts. This quality helps visual designers avoid multiple revisions and ensure the project goes in line with the client's expectations. For instance, a design brief may have typographical stipulations which a design team would need to follow for brand consistency.

Author, Designer and Educator, Mia Cinelli explains important design aspects about typography:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

3. Target Audience

A good design brief reflects strong UX research about the target users. It’s a crucial point to understand the client's target audience—to make informed design decisions that resonate with these intended users. Brands and designers make use of user personas. These help shape their understanding of their users’ and customers’ expectations, needs, pain points and more.

Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains the importance of personas in UX design:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

4. Competitor Analysis

Design briefs can contain valuable insights about what competitors are already doing in the market—including aspects such as design successes and failures. These can serve as vital barometer readings for the market environment a brand proposes to launch its design solution into.

5. Design Goals and Objectives

Clearly defined goals and objectives help distinguish between the overall purpose of the project and the measurable steps to achieve success.

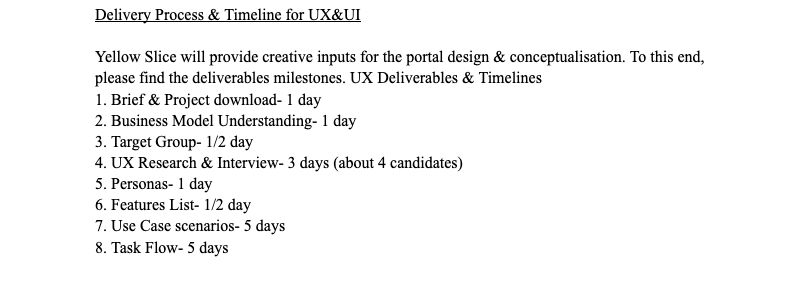

6. Budget and Timeline

It’s critical to outline the project budget and timeline—to manage client expectations and ensure the project remains on track with complete transparency.

Elements of a design brief.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Who Creates a Design Brief and How?

Here's a breakdown of the key contributors to the creation of a design brief:

Client or project manager: The client or the project manager is usually the driving force behind the design brief. They provide essential information like the project goals, target audience, budget and timelines.

Key stakeholders: Input from key stakeholders—such as marketing teams, product managers and end users—is a vital ingredient to create a comprehensive design brief. Their insights help designers understand the specific needs and expectations that relate to the design project.

Design team: The design team—including UX/UI designers and other relevant professionals—also plays a role as far as shaping the design brief goes. Their expertise and understanding of design requirements contribute to the brief's overall content.

Design Director at Société Générale CIB, Morgane Peng explains important aspects of how some stakeholders may view design-related topics:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

To write good design briefs, brands typically need to:

1. Understand the Purpose

Define the project: Clearly outline the scope of the project—that includes the deliverables and the problem the design should solve.

Establish objectives: Specify the goals and objectives the design should achieve. Among these could be to raise brand awareness, improve user experience or launch a new product.

2. Provide Background Information

Brand overview: Give a brief overview of the brand—as well as its values and its target audience.

Market analysis: Share insights about the market, competitors and any design assets that already exist.

3. Outline Design Specifications

Functional requirements: Specify any technical or functional requirements that the design needs to have.

Aesthetic guidelines: Communicate the desired look and feel—that includes any specific brand guidelines or design preferences.

Messaging and tone: Define the messaging and the tone that the design needs to convey.

Professor Alan Dix explains important aspects about design requirements:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

4. Set Expectations

Timeline and budget: Clearly state the timeline for the project and the budget constraints—if any.

Revision and approval process: Outline the process for revisions and approvals so as to manage the expectations.

A realistic timeline is an asset for a good design brief.

© Priya Kavdia, Fair Use

5. Call to Action

Submission guidelines: Give instructions on how to submit proposals or portfolios—and these should be clear.

Contact information: Include contact details for when it comes to any inquiries or clarifications.

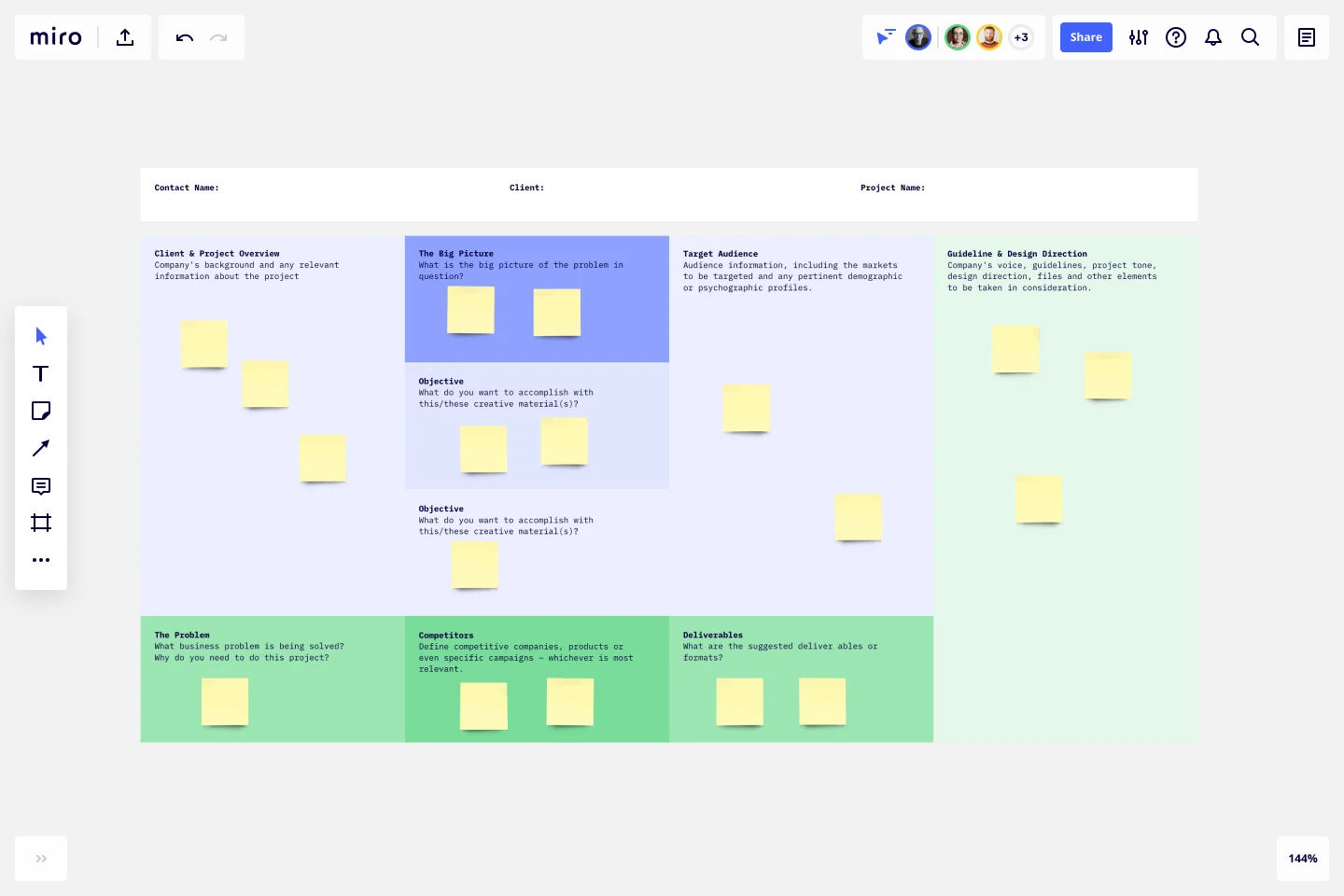

Brands and designers can also rely on design brief templates and software to help them. Here are some notable examples:

Figma: Figma’s FigJam template offers benefits such as how it helps communicate design ideas with great clarity.

© Figma, Fair Use

Miro: Miro’s Design Brief template is a handy tool for brands to help find their place in the industry’s competitive landscape.

© Miro, Fair Use

3. Milanote: Milanote’s design brief templates are available for web and app design to help brands set a course for successful websites and mobile apps.

© Milanote, Fair Use

What are the Benefits of UX Design Briefs?

Particularly notable benefits of UX design briefs are that they:

1. Align Stakeholders

A design brief in UX design is a very important tool for aligning all stakeholders on the project's vision and objectives. It makes sure that everyone from the design team to the client understands the project scope, design requirements, as well as the desired outcomes. This, therefore, fosters a unified approach towards achieving the goals. From clearly stating the project's guidelines, challenges and goals, a design brief helps stakeholders have a mutual understanding—something that's essential for a project to succeed.

2. Streamline the Design Process

The design brief acts as a roadmap for UX designers—it provides them with the information they need to streamline the design process in an effective way. It includes detailed descriptions of the user interface concept, key features and user needs. These items help designers focus their efforts on critical aspects so they won’t waste resources on less important details. This structured approach doesn't just speed up the design process. It enhances efficiency, too, and ensures that the project adheres to the set timelines and budget constraints.

3. Avoid Miscommunication

Miscommunication can lead to project delays, increased costs and designs that don't meet the client’s expectations. A well-crafted design brief minimizes these risks. It gives a clear and concise document—one that outlines all critical project details. What's more, it serves as a reference point throughout the project; plus, it helps keep everyone on the same page and prevent misunderstandings. The design brief also includes a section on the project's scope and deliverables—which further helps to maintain clear communication between the design team and the client.

© Mindmesh, Fair Use

Best Practices for Designers to Use Design Briefs

Designers should consider these tips and best practices so they can make the most of UX and UI design briefs:

1. Collaborate with Clients

Effective collaboration between designers and clients is an absolutely vital part of the way to craft a successful UX design brief. It starts when a brand creates a structured roadmap that enhances communication and makes sure all the parties are on the same page from the beginning. Designers should invite clients to participate in the project—and actively so. That will foster a trusting relationship and give deeper insights into the brand and target audience. Regular meetings and clear communication channels are essential parts of the formula. They permit continuous feedback as well as adjustments to the design brief as the project evolves.

To help collaborate effectively, designers should be sure to adopt the following items:

Feedback mechanism: Establish a clear process for obtaining feedback and approvals throughout the project.

Iterative approach: Embrace an iterative approach; allow for multiple rounds of feedback and revisions to refine the design.

UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains important aspects of iteration in this video:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

2. Ensure Well-Defined, Clear Goals and Objectives

A well-defined UX design brief is clear about outlining its project's goals and objectives. Designers need to work closely with clients if they're to identify the primary objectives of the project. These could include to solve specific user problems or boost user engagement. These goals should be Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Relevant and Time-bound (SMART) to guide the design process effectively—and make sure that all stakeholders have a clear understanding of what success truly looks like. What's more, it's crucial to define the target audience and their needs—components that will directly influence the design decisions.

Designers need to understand the client’s brand and goals—and thoroughly so—before they embark on a fruitful relationship. So, they should:

Do all the comprehensive research they need to do: Conduct in-depth user research to understand the client's brand, target audience and landscape of the industry.

Get aligned with the client's objectives: Make sure that the design brief falls into line with the client's specific goals and objectives for the project at hand.

Prepare for usability testing: Be ready to engage in usability testing so they can validate the design's effectiveness and its user experience.

UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains critical points about user research in this video:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

3. Regularly Review and Update the Brief

To keep the relevance and effectiveness of a UX design brief, some important things to do are to regularly review and update the document throughout the project lifecycle. This practice helps accommodate any changes in project scope, user requirements or market conditions.

Designers should schedule review sessions with all stakeholders—so they can make sure the brief stays aligned with the project's goals and to make necessary adjustments based on the feedback they get. This iterative process doesn't just keep the project on track. It also prevents miscommunications; plus, it ensures that the final product lines up with the client's expectations and user needs.

Special Considerations and Potential Risks of UX Design Briefs

1. Beware of Scope Creep

Scope creep is a common challenge in UX design projects. It happens when the project's scope expands beyond its original objectives; that could be due to various factors—like changes in user requirements, lack of communication between stakeholders or inadequate or poor planning. This expansion can have a large impact on the project's timeline and budget. Plus, it can increase complexity and make it difficult to finish the project.

So, to prevent scope creep, it's crucial for UX designers to involve all stakeholders in the planning process from the beginning and ensure clear communication happens throughout the project's lifecycle. Another key strategy is to manage scope creep so as to set realistic expectations for timelines and budgets. Another is to remain flexible to adapt to changes.

2. Know How to Manage Client Expectations

It’s vital to manage client expectations to make sure that the design brief leads to successful outcomes of projects. To do this, among things it takes are clear communication from the start—to set realistic timelines and budgets—and involving the client in the project’s strategic stages.

Regular check-ins and feedback sessions help keep the client informed and engaged—and minimize misunderstandings. What's more, to create detailed project proposals and have a thorough discovery meeting at the beginning can align both parties on the project's scope and keep scope creep from occurring. When designers maintain open lines of communication and document all discussions, they can manage their clients' expectations effectively and make sure that transparency is a reality throughout the project.

Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach, Todd Zaki Warfel explains how to effectively present design work to clients:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

3. Ensure Accurate and Complete Information

Accurate and complete information in the design brief is a crucial ingredient to avoid misunderstandings and make sure that the project meets the client's needs and expectations. A well-crafted design brief should include detailed information about the project's goals, objectives, target audience, design requirements and any potential challenges.

It's impossible to understate that it’s vital for designers to have a clear understanding of these elements so they can create designs that align with the client's vision and the project's requirements. Regular updates and revisions of the design brief may be needed to reflect any changes or new information. What's more, they'll help ensure that the project stays on track and meets its objectives.

4. Remember Legal and Ethical Considerations

Copyright and permissions: Ensure that the design work complies with copyright laws—and that all necessary permissions are obtained for any third-party assets which the brand uses.

Ethical implications: Consider the ethical implications of the design—especially in sensitive or regulated industries such as medicine or banking.

Client errors in judgement: In some cases, clients may overlook vital aspects of design—like color and contrast aspects—or other important points about accessibility. It’s vital to notify them about the potential of realizing these misconceptions in designs that might fail or run into legal problems.

Watch our video to understand more about why accessibility is such an essential part of design:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

Overall, design briefs are vital blueprints—and tools—that depend on communication, attention to detail and proactive mindsets. Only when UX and UI designers are on the same page as both the client and the users they serve can they produce design works that will exceed expectations. From there, designers can fine-tune truly impactful digital products or services.

© Miro, Fair Use

Learn More about Design Briefs

Take our User Experience: The Beginner’s Guide course.

Watch our Master Class Win Clients, Pitches & Approval: Present Your Designs Effectively with Todd Zaki Warfel, Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach.

Read How to Write a Great Creative UX Brief for a Design Consultancy by Mateusz Kłosiński for further insights.

Consult What is a Design Brief and How to Perfect it? [With Examples from UX Experts] by Priya Kavdia for additional helpful information.

Go to How to Use a Design Brief – Consistency, Coordination and Clarity by Lankitha Wimalarathna for further details.

Questions about Design Briefs

Who is responsible for creating the design brief?

The project owner is the one who usually creates the design brief. They could be the client, a project manager or a senior designer. The project owner sets the definition of the project’s goals, target audience, budget, timeline and key requirements.

A well-crafted design brief is something that makes sure that everyone involved understands the project’s vision and expectations. It should clearly outline the objectives, deliverables and constraints. As it does this, it helps designers get their work in line with the project’s goals—which leads to far more effective and efficient outcomes.

For example, a client who's launching a new website would include their branding guidelines, target audience details and specific functionalities they want. This clarity helps the design team make a website that meets the client’s needs.

Another point is that involving key stakeholders in the creation process can provide valuable insights and be a source of nurturing collaboration. Clear communication from the outset minimizes misunderstandings and revisions, saving time and resources.

Watch our Master Class Win Clients, Pitches & Approval: Present Your Designs Effectively with Todd Zaki Warfel, Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

How detailed should a design brief be?

A design brief should be detailed enough to give clear direction—but concise enough to stay focused. It must include vital information about the project’s goals, target audience, budget, timeline and key deliverables.

Provide clear objectives and expectations to guide the design team effectively. Detail the project's purpose, specific requirements and any constraints. Include background information about the brand, the problem the design needs to solve—and the desired outcomes.

For example, if you're designing a mobile app, be specific about the platform, core features, user personas and any design preferences. This helps the team understand the scope and constraints—which ensures their designs align with your vision.

However, don’t overwhelm the team with too much information. Just focus on what's necessary to complete the project successfully.

Watch Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explain important aspects about design requirements:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

What is the difference between a design brief and a creative brief?

A design brief and a creative brief actually serve different purposes in a project. A design brief focuses on the specifics of a design project. It outlines the project’s goals, target audience, budget, timeline and key deliverables. This brief provides clear direction to the design team—and helps ensure their work runs in line with the project’s requirements.

A creative brief—on the other hand—encompasses a broader scope. It includes the overarching strategy and creative direction for a project; it covers elements like messaging, tone and overall brand vision. What's more, it targets various creative professionals—including designers, writers and marketers—to ensure a unified approach happens across different media and platforms.

For example, a design brief for a website project would detail layout preferences, color schemes and user experience requirements. A creative brief for the same project, though, would cover the brand message, target audience insights and the desired emotional response from users.

So, in summary, a design brief narrows down to design specifics—while a creative brief sets the broader creative vision.

Watch our Master Class Win Clients, Pitches & Approval: Present Your Designs Effectively with Todd Zaki Warfel, Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

What are common mistakes to avoid when one creates a design brief?

When you're creating a design brief, you'll need to avoid some common mistakes if you want to ensure clarity and effectiveness; so, do the following:

Have clear objectives: Clearly define the project’s goals. Ambiguous objectives can lead to confusion and misalignment with the vision of the project.

Have enough detail: Give enough detail about the target audience, project requirements and constraints. If they don't have specific information, the design team may struggle to meet expectations.

Don’t overload with information: Keep the brief focused and concise. Too much information can overwhelm the team and make the main objectives become diluted.

Don’t ignore stakeholder input: Involve key stakeholders in the process of creating the brief. Their insights can give valuable perspectives and make sure that all expectations get addressed.

Set realistic deadlines: Overly ambitious timelines can work against the quality of the work and make things more stressful for the design team.

Stick to budget constraints: Be clear about budget limitations. This helps the team make more informed decisions and keep unnecessary costs at bay.

Watch Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explain important aspects about design requirements:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

How can a design brief improve communication between clients and designers?

A design brief does this by giving a clear and detailed outline of the project's goals, requirements and expectations. This document makes sure that both parties understand the project's scope and objectives from the beginning.

First, the design brief is what defines the project’s purpose and target audience. This helps designers create work that falls in line with the client’s vision. Clear objectives prevent misunderstandings—plus, they reduce the need for revisions.

Second, the brief includes specific details about the design requirements. These could be preferred styles, color schemes and functionality, for example. This information guides designers, and it helps them meet the client’s expectations in a more accurate way.

Third, the design brief sets realistic timelines and budgets. This transparency helps manage client expectations—plus, it lets designers plan their work efficiently.

Last—but not least—the design brief serves as a reference point all through the project. Both clients and designers can refer to it so they can make sure their project stays on track and ends up meeting its goals.

Watch our Master Class Win Clients, Pitches & Approval: Present Your Designs Effectively with Todd Zaki Warfel, Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

Design Director at Société Générale CIB, Morgane Peng explains important aspects of how some stakeholders may view design-related topics:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

What should the timeline and milestones section of a design brief include?

In the timeline and milestones section, be sure to put in key dates and deliverables so you can help make sure the project stays on track.

To start, outline the project's start and end dates. This will give a clear timeframe for the entire project.

Next, list major milestones. They're significant checkpoints in the project. These could include the completion of research, initial design drafts, client reviews and final revisions. Each milestone should have a specific deadline. Work in intermediate deadlines for smaller tasks that lead up to each milestone. For example, you'll want to set dates for initial concept presentations, user testing and feedback sessions. This will help the team manage their time and ensure steady progress. Clearly state who's responsible for each task and milestone. To assign responsibility is something that can prevent confusion—and ensure accountability.

Finally, consider potential risks and include buffer time in the schedule to handle any unexpected delays. This flexibility helps keep thing things on track with the project timeline—even should issues arise.

Watch our Master Class Win Clients, Pitches & Approval: Present Your Designs Effectively with Todd Zaki Warfel, Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

Design Director at Société Générale CIB, Morgane Peng explains important aspects of how some stakeholders may view design-related topics:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

How do you specify deliverables in a design brief?

Be clear about outlining what you expect the design team to make. Start with a list of all the key deliverables. These could include wireframes, mockups, prototypes, final designs and any other outputs of the project.

Describe each deliverable in detail. For instance, if you need wireframes, state the number of pages or screens and the level of detail called for. For prototypes, mention the platform (web, mobile) and the functionalities that need to go in.

Set clear deadlines for each deliverable. This helps the team manage their time—plus, it ensures they complete everything on schedule.

Include the format and the specifications for each deliverable. State whether you need digital files, printed materials—or both. Mention what the preferred file formats (e.g., PDF, JPEG) are and any technical requirements (e.g., resolution, dimensions).Identify the person who's responsible for each deliverable. This creates accountability—and ensures that everyone knows their roles and responsibilities.

Watch our video about wireframing for more information about this valuable design activity:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

How do you address budget considerations in a design brief?

To address budget considerations in a design brief, do these:

Clearly outline the project's financial constraints. To start with, state the total budget that's available for the project. This helps the design team understand both the scope and the scale of the project.

Break the budget down into specific categories. Include costs for design services, materials, software and any other relevant expenses. This detailed breakdown provides transparency—plus, it helps the team allocate resources effectively.

Be specific about any fixed costs or hourly rates. If the project includes multiple phases, allocate the budget for each phase separately. This ensures the team manages funds in an efficient way throughout the project.

Include guidelines on how to manage additional expenses. State whether there's any flexibility in the budget—and how to handle unforeseen costs. This will prepare the team for potential financial challenges that might crop up.

Last—but not least—clarify the payment schedule. Indicate when payments will occur, like at the completion of certain milestones or on specific dates. This makes sure that both parties agree on financial expectations as well as timelines.

CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers explains the return on investment (ROI) of UX—an important consideration for design-related budgets.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

What tools can help to create and manage design briefs?

Several tools can help with that. Here are some:

Trello: Use Trello to organize tasks and milestones. Its visual boards and cards make it easy to track progress and manage deadlines.

Asana: Asana helps manage projects by letting you assign tasks, set deadlines and monitor progress—and makes sure that everyone stays on the same page.

Google Docs: Google Docs enables the collaborative writing and editing of design briefs. Multiple team members can work on the document at the same time—and make sure everyone’s input is included.

Notion: Notion offers a flexible workspace where you can create, share and store design briefs. It combines notes, databases and task management in one place.

Milanote: Milanote is ideal for creative projects. It lets you create visual boards with notes, images and links—and helps you organize and present ideas clearly.

Slack: Slack facilitates communication between team members. You can share updates, discuss details and make sure that everyone stays informed about the project’s progress.

Design Director at Société Générale CIB, Morgane Peng explains important aspects of how some stakeholders may view design-related topics:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

How do you evaluate the effectiveness of a design brief?

To evaluate the effectiveness of a design brief, make an assessment of how well it guides the project and meets its objectives.

To start with, review the clarity of the project’s goals. An effective design brief should clearly state the project’s purpose, target audience—and desired outcomes.

Check if the brief provides detailed requirements and constraints. Effective briefs include specific information about design elements—these could be color schemes, typography and functionality, for instance. This will help the design team understand what the client expects. Examine the timeline and milestones section. An effective brief sets realistic deadlines, and it includes key milestones—to help ensure that the project stays on track.

Collect feedback from the design team. Ask them if the brief gave them a clear direction—and if they faced anything that was ambiguous. Their input can highlight strengths and areas for improvement next time.

Finally, evaluate the project’s outcome against the brief’s objectives. Determine if the final design meets the goals and expectations that the brief outlined. If it does, then the design brief effectively guided the project.

Watch our Master Class Win Clients, Pitches & Approval: Present Your Designs Effectively with Todd Zaki Warfel, Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach.

Design Director at Société Générale CIB, Morgane Peng explains important aspects of how some stakeholders may view design-related topics:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

How do you handle changes to a design brief during the project?

To handle any changes during the project, try taking these steps:

Assess the change: Evaluate the proposed change to understand its impact on the project's goals, timeline and budget. Work out if the change is necessary—and if it's beneficial.

Communicate with the team: Inform the design team—and stakeholders—about the change. Explain why the change is needed and how it is going to affect the project. Clear communication is a sure way to seeing that everyone understands and supports the modification.

Update the brief: Revise the design brief to work those new changes into it. Make sure to document all the updates—and that includes any new requirements, deadlines or budget adjustments. This will keep your brief accurate and current.

Adjust the plan: Modify the project plan so that it now incorporates the changes. Update the timeline and milestones—and reallocate resources if needed. Make sure that the team knows about the new plan.

Monitor progress: Track the project's progress to check that the changes get implemented correctly. Regular check-ins with the team help address any issues that might crop up due to the change.

Watch our Master Class Win Clients, Pitches & Approval: Present Your Designs Effectively with Todd Zaki Warfel, Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach.

CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers explains the return on investment (ROI) of UX—an important consideration for design-related budgets.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

What should you do if there is a disagreement over the design brief content?

If there's a disagreement over the design brief content, try taking these steps to resolve it:

Communicate openly: Arrange a meeting with all parties who are concerned. Discuss the points of disagreement clearly—and calmly. Ensure everyone has a chance to voice their concerns and perspectives.

Clarify objectives: Revisit the project’s goals and objectives. Be sure that everyone understands the purpose and the desired outcomes of the project. This can help align differing views.

Seek compromise: Look for common ground and areas where some compromise can happen. Aim to find a solution that addresses the concerns of all parties while staying true to the project's goals.

Consult stakeholders: Involve key stakeholders if that's needed. Their input can provide additional insights and help mediate the disagreement.

Document changes: Once you do reach an agreement, update the design brief to reflect the resolved content. Be sure that all parties review and approve the changes.

Move forward: Communicate the updated brief to the entire team and then continue with the project—making sure everyone is on the same page.

Watch our Master Class Win Clients, Pitches & Approval: Present Your Designs Effectively with Todd Zaki Warfel, Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach.

Design Director at Société Générale CIB, Morgane Peng explains important aspects of how some stakeholders may view design-related topics:

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

What are some highly cited scientific articles about the subject of design briefs?

Koronis, G., Silva, A., Kang, J. K. S., & Yogiaman, C. (2020). How to best frame a design brief to maximize novelty and usefulness in idea generation. Proceedings of the Design Society: DESIGN Conference, 1, 1745-1754.

This publication presents a study that investigates how different types of design brief framing influence the novelty and usefulness of ideas that come up during conceptual design ideation sessions. The researchers conducted experiments with student designers—giving them design briefs framed in three conditions: a control group with a succinct brief, an abstract group with a conceptual brief, and a group who had various example solutions representing a concrete framing. The resulting design concepts were evaluated for both novelty and usefulness. The findings suggest that abstract briefs do promote more novel ideas—while concrete briefs with physical examples lead to more useful but less novel solutions. The study contributes insights into the impact of design brief representations on creativity metrics—highlighting the trade-off between novelty and usefulness. The authors discuss the implications for crafting effective design briefs to stimulate desired levels of creativity and appropriateness in design outcomes based on the intended goals of the project.

Sosa, R., Vasconcelos, L. A., & Cardoso, C. C. (2018). Design briefs in creativity studies. Proceedings of the DESIGN 2018 15th International Design Conference, 1801-1810.

This publication examines the diversity of research practices in experimental studies of early conceptual design—with a particular focus on the design briefs used for prompting ideation from participants. From analyzing 75 recent studies from leading design journals between 2012 and 2017, the authors reveal a high degree of variance in how design briefs are presented, the number and experience level of participants, and the time that's allocated for ideation tasks. The study highlights the lack of consistency in these critical aspects of experimental design—which can impact the validity and replicability of findings. The authors propose three indicators—polysemy, innovation and communication—to assist researchers in preparing effective design briefs. What's more, they introduce an "experimental design canvas" as a framework to structure the design of creativity experiments and facilitate the synthesis of appropriate design briefs. This research contributes to improving the rigor and comparability of studies in the field of design creativity by providing guidelines and tools for crafting well-designed briefs and experimental conditions.

What are some highly regarded books about design briefs?

Lasky, M. (2023). HOW TO TAKE A WEB DESIGN BRIEF.

HOW TO TAKE A WEB DESIGN BRIEF by Matt Lasky is a comprehensive guide that emphasizes how important it is to craft a meticulously detailed brief for successful web design projects. With over two decades of experience in digital agencies, the author shares insights, guidance and real-world examples to help readers achieve alignment and consensus from the project's inception. The book aims to eliminate common web project stumbling blocks—such as struggles with design approvals, last-minute team additions, scope creep and misaligned expectations. From mastering the art of creating a well-crafted design brief, readers can navigate the complex landscape of web projects and raise their chances of success.

Earn a Gift, Answer a Short Quiz!

- Question 1

- Question 2

- Question 3

- Get Your Gift

Try Again! IxDF Cheers For You!

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

- Question 1

- Question 2

- Question 3

- Get Your Gift

Congratulations! You Did Amazing

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

Check Your Inbox

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Literature on Design Briefs

Here's the entire UX literature on Design Briefs by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Design Briefs

Take a deep dive into Design Briefs with our course User Experience: The Beginner's Guide .

It's Easy to Fast-Track Your Career with the World's Best Experts

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your experts for this course:

Don Norman: Father of User Experience (UX) design, author of the legendary book “The Design of Everyday Things,” and co-founder of the Nielsen Norman Group.

Rikke Friis Dam and Mads Soegaard: Co-Founders and Co-CEOs of IxDF.

Mike Rohde: Experience and Interface Designer, author of the bestselling “The Sketchnote Handbook.”

Stephen Gay: User Experience leader with 20+ years of experience in digital innovation and coaching teams across five continents.

Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

Ann Blandford: Professor of Human-Computer Interaction at University College London.

Cory Lebson: Principal User Experience Researcher with 20+ years of experience and author of “The UX Careers Handbook.”

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!