Don Norman on How to Move Up in a Company: Think Big!

- 580 shares

- 3 years ago

The secret of Don Norman’s success is that this cognitive science and usability engineering expert advocates speaking in everyday language, taking a systems point of view and living a long life. By striving to emulate these and adopting a generalist approach, designers may find they can enjoy and use similar influence.

“Design, to me, I found was a perfect field because I could use all the science I knew, all the engineering I knew, all of the stuff about people and about technology, but I could produce and build things that were used by millions and millions of people.”

— Don Norman, “Grand Old Man of User Experience”

Learn how to succeed as a modern designer.

Well, people sometimes ask me what's the secret of my success – and the real answer is, I don't know. I have a strange background because I started off in love with technology. I was in love with radios at first because radios were the first thing I ever encountered where I couldn't see how it worked. Mechanical devices you can sort of see how it works; you can take it apart; you can turn here and see it turns there;

push here, you can see it lifts there. Radios – it's all invisible. So, I got really interested in this invisibility of electrons and electromagnetic waves. And so, I decided to go get an engineering degree so I could work on electrical engineering. And so, I went to MIT and got a degree in Electrical Engineering at MIT. And then, I thought I would go to industry, but for complex reasons,

I ended up going to graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania where again I was learning more about electrical engineering. But at that point computers were just starting to exist. There were only a couple. We had one at the University of Pennsylvania. In fact, I was really interested in computers, and the University of Pennsylvania was where the first digital computers were invented in the United States, called the EDVAC and the ENIAC.

And so, I went there, but none of the people who did the computers were there anymore. So, I didn't know what to do. I finished a Master's Degree in Electrical Engineering. But what I really wanted to do was computers, and they didn't have a program for computers. "Wait," they said, "we're going to start one. In a couple of years, we're going to start one, and you can be the first graduate student." But I didn't want to wait. And just then the Psychology Department started up. Well, actually it had been in existence for a long time, but they got a new chair,

and the new chair was a physicist and they were hiring new people like people who were mathematicians. And I talked to the chair, who said I didn't know anything about psychology. "Wonderful!" he said. "Come into the Department." So, I went to the department and I was immediately told I didn't know enough mathematics. I had six years of engineering mathematics, more than anybody, any of the other students, but nope – I had to learn more math because this was approaching things differently.

The field of psychology in those days was behaviorism; it was all people who denied that anything went on inside the head or denied that that mattered at all. What they cared about was what the behavior was. And I said "No. I want to understand the *mechanisms*." And so, I helped develop a field eventually. I started off studying the things I was really good at, which was the sensory system. I did my thesis on acoustics, psychoacoustics, on how we hear sounds.

And my first job was at Harvard. So, I did lead this sort of privileged life. I somehow or other got into MIT and then Penn. And then at Penn, when I graduated my advisor simply said, "So, where do you want to go now?" And we talked about schools, and we decided it should either be MIT or Harvard. And so, he got me appointments. I went to both places and decided uh, MIT I know already; I'll go to Harvard. It doesn't work that way today.

At Harvard, I entered something called the Center for Cognitive Studies, which was really interesting. I had never heard the word "cognitive" – I didn't know what it was about. And it was at Harvard that I first started to learn real psychology, and I discovered the British psychologists who were doing really interesting things, looking at mechanisms. And I was in the Center for Cognitive Studies. That was really wonderful and exciting, run by two people called Jerry Bruner and George Miller, two very, very well-known psychologists at the time.

But I was appointed to be an instructor in psychology, and in my first department meeting George Miller introduced me to the faculty and B. F. Skinner, the world's most famous psychologist at the time, stood up and denounced me and denounced the work I was doing. So, I've learned that's a good thing! If you want to do really important work, you're going to make a lot of people unhappy. If you want to change the way people are doing things, people will be *against* you.

In fact, if people are all supporting you and saying "That's wonderful!", you're doing the *wrong* thing. You're doing what everybody else is doing, and that's not the way to change the world. So, I wanted to change the world. I wanted to bring all the mechanisms I'd learned about as an engineer into the field of psychology. And so, I started studying *memory* and did a lot of work in memory while I was at Harvard, trying to understand how the memory systems worked. And memory was almost never studied. It was really amazing.

And then, just then the University of California, San Diego opened up, and so I was hired there. So, I was the second batch of people in the Psychology Department. No student had graduated from the university yet. It was a small, isolated campus in the northern part of San Diego. Today, it's a world-famous university, one of the top in the world. But at that time nobody had ever heard of it. But it was interesting because they started by hiring Nobel Prize laureates.

And then they went down this – very senior professors and then more junior professors and post-doctoral fellows and graduate students and eventually undergraduates. By coming from the top down, they got some really good people. So, I started with a friend, Peter Lindsay. We decided we wanted to *change* psychology. And we wrote a book called "Human Information Processing". And we taught a course in basic to freshman about thinking about psychology,

– what is the mechanism that makes all this work? And that's a field that eventually became Cognitive Psychology and then Cognitive Science because I thought psychology was too narrow and too limited and I wanted that students ought to learn about artificial intelligence and computer science and neuroscience and linguistics and philosophy and the social sciences. And so, we started the Cognitive Science Department, which was a combination of everything.

Now, along the way we had a major problem with one of our nuclear power reactors. It's called Three Mile Island; that's the location; it was on the river and this is the island – it's three miles below the starting point. And that's where the nuclear reactor was, and basically it destroyed itself. And I was called up by a committee from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission

to be on this panel to go in and understand why the operators made their errors that made the problem even worse. And we went in and we studied it, and the people I was with were human factors experts. And I thought they were excellent. And what we decided was those operators were very smart, they made very sensible decisions, but if you wanted to design a plant that *caused errors*, you couldn't have done a better job than they did.

So, it was the *design* that was the problem. And that made me say, "Oh, I'm a psychologist, so I understand people. And I'm an engineer so I understand technology. *That's* where I ought to be – I ought to be trying to understand how to design technology that makes it better for people." And so, I started doing that, and I started working with NASA on aviation safety. And then, as computers came out we developed a research group that started to work on

making computers more understandable, easier to use, easier to understand. Some of the fundamental principles we developed are the principles that in the early Apple computers – the Human Interface Guidelines book that Apple developed, which has been wonderful, was done by people at Apple, but some of them were my students and following a lot of the work that we'd developed at San Diego. And, in fact, I took a year's sabbatical.

I went to England, and I was in England – Cambridge, England – and I discovered that I couldn't even open the doors. The doors – I would pull and they had to be pushed, or I would push and they had to be lifted, or I would lift and they had to be slided to the right. And it was crazy! Why was it so difficult to use everyday things? And so, I realized that the principles that we'd been studying for nuclear power reactors or complex

airplanes – aviation safety – and, for that matter, the new computers applied even to doors and light switches and water faucets, or water taps as they call them in Britain. And so, I wrote a book called "The Psychology of Everyday Things" and that was my beginning. And, actually, I didn't even know there was a design profession that existed. And I was writing the book where I met a few real designers who told me, "Hey, you know, you're pretty naive about what's going on here."

And I therefore fortunately discovered that *before* we published the book, so I modified the book. But that also got me more interested in doing things that made a difference to the world that people would *use*, and so I took an early retirement from the university – so, I retired from the university – my first of five retirements. I retired in 1993. And I went to Apple, where I became first an Apple Fellow, which meant "Hey! I had no responsibilities. I could do anything that I wanted!"

And I thought that Apple had really great, fantastic stuff but that it was suffering from problems. And I said – I gathered a couple of people around me and said, "Let's try to fix these problems!" And so, we invented the term *user experience* and I called myself the User Experience Architect of Apple. And this user experience group went about trying to make sure that Apple maintained

the high quality of usability and understandability in its products. And that's when I first started to meet real designers, the designers who were working – they were all industrial designers – in the Design Group at Apple. So, that's kind of how I got here. So, why am I so well-known? Well, there's a couple of reasons. I think one of them is because I speak in *everyday language*. I did a lot of work with one of my colleagues, a professor

in the Psychology Department at UC San Diego. And we published a lot of papers together. He was a really deep thinker, really intelligent, did tremendous groundbreaking work. And he complained a bit about my writing because when we wrote together he said, "The problem with Don's writing is he writes so clearly that you can tell that you're wrong." It's amazing how many academics like the complex, convoluted style of reading

that's really hard to understand because – also – if it's really hard to understand, this must be very profound, right? And so, people don't even notice that what they're talking about is pure nonsense. Well, I have trouble understanding a lot of this stuff and I struggle with it. And when I finally understand it, then I can write it and because I know the problems that I had in trying to understand it, so I write it in clear, understandable language.

That is surprisingly unusual in the scientific literature or the design literature. And the second thing is I do try to take a *systems point of view* – I try to take a *broader* point of view to try to understand the important implications of what I'm doing, and that is surprisingly rare. And the other important thing which I think is very important, which I recommend highly to you,

is to *live a long life*. In fact, when I went to Harvard there was a faculty member there, a very famous person in sensory psychology – S. S. Stevens – and he said: In science, you're always fighting with your competitors – that's the way science works because we learn to – when we read a new paper, we immediately look to see where the flaws are,

and we want to point them out to other people, and that's important, actually, because this back and forth is how science gets better and better and better. But, therefore, you always have opponents. And he said, "The way that you succeed over your opponents is to outlive them." And he was right because a lot of the opponents that he had died, and so he was sort of victorious. And then, when he died – today only the specialists in the field

– of a few fields in sensory psychology remember him because, well, when you die you get forgotten. So, I highly recommend you live a long life and I've managed to do that quite well.

Jerome Bruner by Poughkeepsie Day School (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/poughkeepsiedayschool/10277703145

Three Mile Island by Nuclear Regulatory Commission (CC BY 2.0)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/nrcgov/17674734289

TMI-2 Control Room in 1979 by Nuclear Regulatory Commission (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/nrcgov/7447591424

Stevens, Stanley Smith by Mark D. Fairchild

Fairchild M.D. (2016) Stevens, Stanley Smith. In: Luo M.R. (eds) Encyclopedia of Color Science and Technology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8071-7_314

This is a photograph of B.F. Skinner. by Msanders nti (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:B.F._Skinner.jpg

EDSAC by Copyright Department of Computer Science and Technology, University of Cambridge. Reproduced by permission.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EDSAC_(12).jpg

Two pieces of ENIAC currently on display in the Moore School of Engineering and Applied Science, in room 100 of the Moore building. Photo courtesy of the curator, released under GNU license along with 3 other images in an email to me.

Copyright 2005 Paul W Shaffer, University of Pennsylvania. by TexasDex (CC-BY-SA-3.0-migrated)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ENIAC_Penn1.jpg

Biblioteca de la UCSD by Belis@rio (CC BY-SA 2.0)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/belisario/2700271091/

This is an image of a place or building that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places in the United States of America. Its reference number is 78002444. by Bestbudbrian (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:North_facade_of_College_Hall,_Penn_Campus.jpg

Atkinson Hall at the University of California, San Diego, housing the Qualcomm Institute—the UC San Diego division of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology (Calit2) by TritonsRising (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Qualcomm_Institute.jpgDon Norman became an influential figure for no small reason. A childhood fascination with electrons and electromagnetic waves led him to study electrical engineering at MIT. Slightly later, the University of Pennsylvania — where Norman was attending graduate school — was the home of some of the earliest computers. Norman wanted to get involved with computers, but settled on psychology. However, he wanted to study the mechanisms involved in psychology and began working at the Center for Cognitive Studies at Harvard. Here, renowned psychologist B.F. Skinner once denounced Norman’s work. This, Norman found, was a good thing; you need courage to do anything worthwhile — many people who follow established paths will dislike you for exploring beyond their frame of reference.

Norman then studied memory systems at Harvard (memory was a virtually-unknown study subject) before relocating to the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Later, he and co-author Peter Lindsay wrote Human Information Processing: An Introduction to Psychology, a work examining how people process information — investigations that would sow the field of cognitive psychology. Considering psychology too narrow, Norman expanded into artificial intelligence, neural science, philosophy and other disciplines, and the UCSD’s Cognitive Science department was born.

In 1979, the Three Mile Island nuclear-power-station accident spotlighted the significance of Norman’s work and expansive knowledge base. Asked to investigate, Norman found the problem was the control room’s design. This incident drove him to design technology that improved what people experience. He began working on aviation safety for NASA, and strove to make computers easier to use (notably by working with Apple).

A year’s sabbatical at Cambridge University diverted Norman’s attention in an unexpected direction. Finding he couldn’t open some doors — their designs didn’t indicate to push or pull — Norman realized that principles governing nuclear safety and sophisticated devices also applied to basic artifacts. This inspired him to write The Psychology of Everyday Things. Later, he began the first of several retirements — at Apple, where he discovered some problems. Here, he coined the term “user experience,” became Apple’s user experience architect and began meeting designers in earnest. His influence has since extended to touch countless aspects of design. Still, Norman pressed on: encouraging designers to tackle the world’s biggest challenges with fundamental approaches such as 21st century design, human-centered design and humanity-centered design. His concern about the state of the world reflects his commitment to help designers realize they can make a difference if they apply human-centered design insights to the complex problems that plague our planet. And his work with the Interaction Design Foundation has resulted in a course — titled Design for the 21st Century — for designers to learn how they can achieve this.

© Daniel Skrok and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

What can we learn from Norman’s experience? While Norman says he doesn’t really know what the secrets of his success are, he yields several points:

© Roman Kurachenko and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

Everyday language makes life easy for the countless users, students and readers Norman has influenced. Academics traditionally write in complex, confusing ways.

The systems thinking viewpoint Norman takes to what he sees will help you decipher many complexities. That can also help you become influential, especially as you seek to rise in the organizations you help.

Old age is a privilege denied to many; it’s naturally difficult to “emulate.” Still, a powerful way to ensure “victory” over those who might stand in your way or attempt to mute your influence is to outlive them. Plus, providing the new areas and answers you explore are worthwhile ones, you can enjoy long-lasting effects of the positive outcomes you’ll have achieved.

Norman teaches a further key to success. Learn here how to leverage the power of being a generalist:

You know, I've lived a really interesting life. I've had many different careers. I started off as an electrical engineer. In fact, I got *two* degrees in Electrical Engineering, and I worked for electronics companies. And then, I went and I got a PhD in psychology, but a field that was called at that point *mathematical psychology*,

which eventually became *cognitive psychology* and then became *cognitive science*, a field that – well, it used some modern techniques. And so, my electrical engineering background turned out to be of great value in psychology because I was able to introduce new concepts into psychology, new concepts for psychology but actually old concepts in engineering. And my life has been like that – as I change fields and change areas,

quite often the knowledge I'd gotten from the earlier fields turns out to be really useful in the new fields. So, I became an academic; I became a professor – much to my surprise; I never intended that. I taught first at Harvard University, and then I joined the University of California in San Diego where we introduced a field that we called *human information processing*, which is to use basically what we understood about information theory to apply to

psychology, to apply to understanding the person. I won't go into my whole history, but eventually what happened was I got called in to study *human error*. There were some major accidents in nuclear power plants, and we were asked to say why things were so bad; why did the operators make those errors? And the team I was on was really good, and what we did is we analyzed everything and

we came back and said the operators were really intelligent, and they did the best job they could. The problem was that the plant was so *badly designed*. And that's when I started switching to design because I realized that my background in understanding people *plus* my background in technology was perfect for trying to understand how to design technology so people could use it properly. That also meant in academics I wanted to change from psychology,

which was too narrow, I felt. So, I helped develop a field that is today called cognitive science, which includes a wide variety of older fields like neuroscience, like psychology, like linguistics, sociology, anthropology, computer science, especially artificial intelligence. And over the years the work expanded too. We started looking at why people were having difficulty understanding their computer systems.

And that led to the field that today is called human-computer interaction. And that work was so interesting. And because there were so many new computers coming out – the Apple II, first – you may not remember that; it's an old machine. But then Xerox Palo Alto Research Center – I became a consultant with them, and they were developing this new kind of computer that really revolutionized the way computers are done today. And that was called the Alto.

However, that led eventually to the Apple Macintosh. And the Apple Macintosh of those early days is still remarkably familiar. It's very similar to the systems we have today both from Apple – the Macintosh Operating System and from Windows, from Microsoft Windows. So, I got more and more interested in what was happening in industry and so I retired from the university and went to Apple, where I became the Vice President of Advanced Technology.

And that's where for the first time I met real designers who were actually designing the new Macintoshes. So, design, to me, I found was a perfect field because I could use all the science I knew, all the engineering I knew, all of the stuff about people and about technology, but I could produce and build things that were used by millions and millions of people.

And nothing is more exciting than being able to say, "I took part in that, and it's used by so many people around the world. It has changed their lives." What's really neat about design is we *build* things, we *create* things. Sometimes they're physical things like – well, like the computer, the physical computer. And sometimes they are digital things like apps and like the software that's inside the computers.

And sometimes they're procedures like if you're in the operating room in a medical school or in a hospital, how do you actually go about *doing* the operation? Because there might be seven, eight, nine, even ten people all involved in treating the patient; so, how do they synchronize? How do they know what to do? That's a design problem. So, design covers a wide range of things. So, how do you get educated in design?

I *never* got educated in design – I was *self-educated*. But what I brought to bear was first of all a huge amount of previous knowledge about how the world works – about politics, economics; and when I was at Apple, I learned about how businesses work and the importance of the financial side of business, which I had never thought about before, and supply chains and finding the right materials and making sure that a product that you are designing works for millions and millions of people,

and when they get into *difficulty* with the product, designing so they can understand what had happened. You need to know a tremendous amount of different areas. And if you know so many different areas, it means you aren't expert about any of them because there are many specialties where you have *deep, narrow knowledge*. And these specialties are comprised of – you know – they're experts, experts in any given area, and we need those people – that's how we get detailed, wonderful information.

However, if you're a designer, you have to have *broad knowledge*. This way, you have to know *about* all those different disciplines, but how you put them together and how that's done – the designer does that. And that means the designer has to go and talk to each of the specialized disciplines and help them bring together this final product. So, you have to be a *generalist* to be a designer; you have to know a tremendous number of different things, usually none of them very deeply, because I kind of think of it this way:

The amount of knowledge that you're learning to be a specialist is *narrow and deep*. So, think about the *area* – deep and narrow. The area is how much knowledge you have. If you're a generalist, on any given area you don't know much but you know many areas. So, think of it as *broad* – it's wide and not very deep. But the area is the same. So, the amount of knowledge you must have is about the same.

Now, here's the question: How do we train designers? Or if you are already a designer, what do you need to know to be successful? I also want to point out that you don't necessarily need to get this training in a design school. You can do it by yourself. So, you can teach yourself all the material you need to know to become a successful designer.

But in the 21st century we're moving to more and more complex problems that do require the talents of a designer. And these new kinds of problems are going to require new types of knowledge and new types of learning on the part of the designer.

Apple's headquarters at Infinite Loop in Cupertino, California, USA. by Joe Ravi (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AppleHeadquartersin_Cupertino.jpg

Apple Museum (Prague) Apple II (1977). by Benoit Prieur (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AppleMuseum(Prague)AppleII_(1977).jpg

Apple Museum (Prague) Macintosh LC (1990). by Benoit Prieur (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AppleMuseum(Prague)MacintoshLC(1990)(cropped).jpg

Lucens, Versuchsatomkraftwerk by Josef Schmid (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Controlroom-Lucensreactor-1968-L17-0251-0105.jpg

Cali Mill Plaza, Cupertino City Center, at the intersection of De Anza and Stevens Creek Boulevards in Cupertino. by Coolcaesar (CC-BY-SA-3.0-migrated-with-disclaimers)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CupertinoCityCenter.jpg

Atkinson Hall at the University of California, San Diego, housing the Qualcomm Institute—the UC San Diego division of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology (Calit2) by TritonsRising (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Qualcomm_Institute.jpg

Computer Museum: Xerox Alto Workstation by Carlo Nardone (CC BY-SA 2.0)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/cmnit/2041103802

Xerox PARC in 1977; an un-busy weekend view from across Coyote Hill Road. Shot on an Olympus Pen-F, half-frame Kodachrome 64 slide; scanned by Pixel 3 phone with Moment 10X macro lens. by Dicklyon (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:XeroxPARCin_1977.jpg

Indeed, Don Norman had moved from one field to another to explore interests geared principally around human cognition — resulting in his ability to consider broader cause-and-effect chains of designers’ decisions. For example, with the nuclear power accident, he leveraged elements from engineering and psychology. Yes, Norman was self-taught; plus, his “timing” was remarkable. Nevertheless, you’ll find a powerful vantage point when you become a generalist:

You must know many different things, without sinking time into becoming expert at them. Instead, you consult many specialists, tap their in-depth expertise and bring them together to create a final product.

You can learn quickly. Everything you learn makes it easier to learn something else, and then the next new thing. You can then apply this snowballed knowledge to each new challenge.

You can decode complex situations more easily by viewing them from a generalist angle: a world of complex socio-technical systems, of interconnected parts of business, supply chains, technology and so much more.

Overall, remember; it takes courage to do things that will improve the world, one piece at a time.

Read Don Norman and Peter Lindsay’s ground-breaking work on Human Information Processing.

For a wealth of insights from Don Norman on the design of everyday things, check out his highly influential book.

Take our 21st Century Design course.

Hi, I'm Don Norman. I want to talk about 21st century design. I've transformed myself from – well, in the beginning, a technology nerd. And all I cared about was the latest circuit design and the latest new device or the latest new technology. And I've changed to now where I'm worried more and more and more about the state of the world,

about the many societal issues that we are facing – some of them are political; some of them are economic; some of them have to do with education, hunger, food, pure water, sanitation. When I look at some of the major problems in the world that we are trying to address, and I take those problems from the United Nations, which has a list of 17 sustainable development problems that are extremely critical. Those are not new problems; they're well known.

There's all sorts of issues there that many, many very talented people have been trying to solve for a long time. Many governments, the United Nations itself, many foundations – almost all of these systems have *failed*. They've spent *billions* of dollars, taking *decades* of time. And most of the time, they fail. And even when they do succeed, they only succeed for a small part of the problem and usually taking many, many more years than they had expected

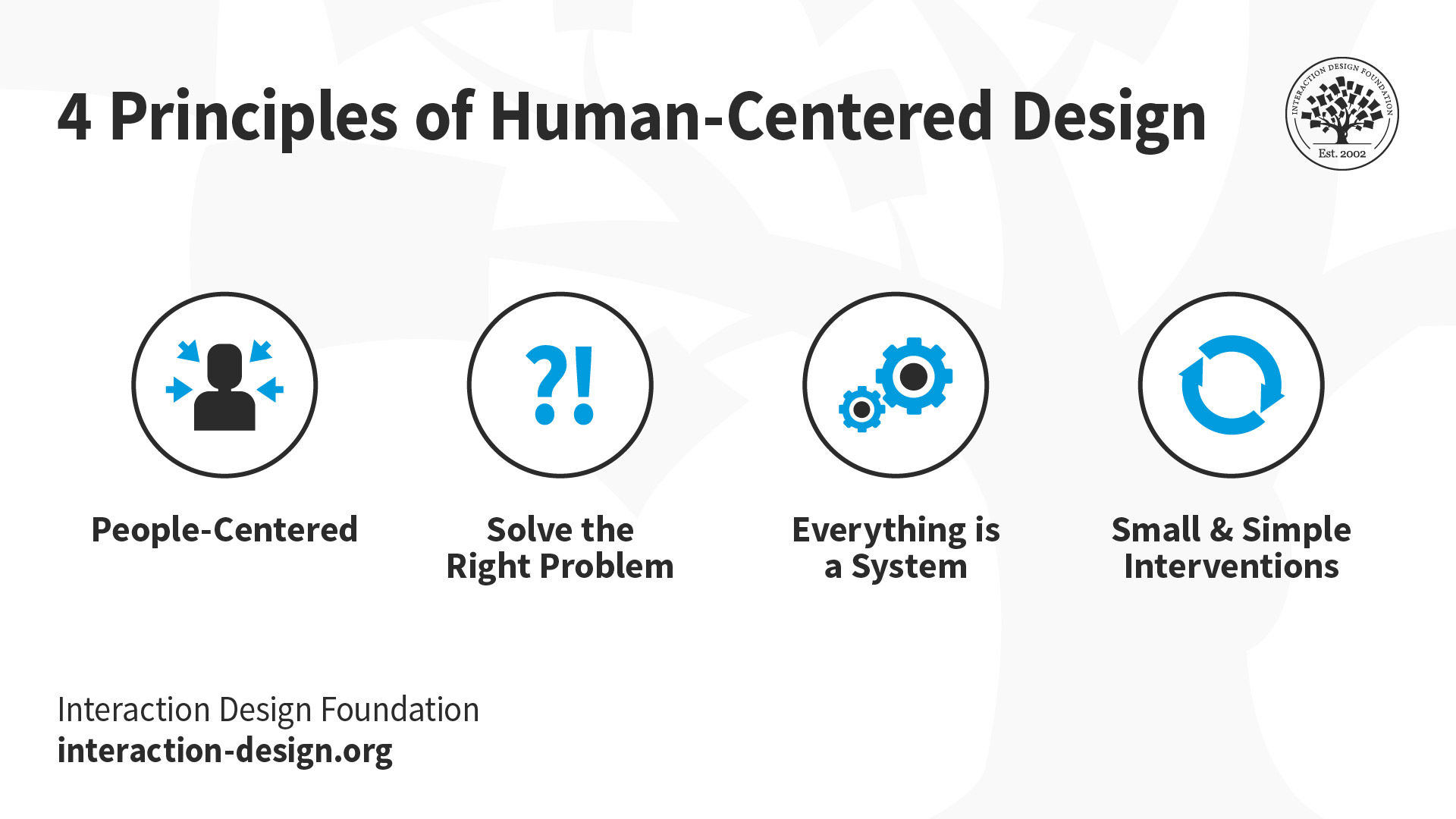

and costing two or three or four times as much money as they expected. And I'm talking about money measured in *billions* of dollars. What can *designers* offer? Here's what we can offer. Design is a mechanism because designers *do things*. They go out and they change the world. But we have to move design from designing small, simple things to designing *systems*, to designing political systems,

to designing *solutions* to clean water and education and healthcare. How do we do that? Well, over the years I've come to develop something which is now called *human-centered design*. Designers have that skill – by finding the right problem, bringing together the systems, and always a focus upon the people – or, if you like, upon *humanity*. So, that's the power that designers have

— *if* — here's the "if": Are you a designer? If you are, are you capable of working on a problem like that? Most designers are not. They can *learn*, but they weren't trained to do problems of this sort. You don't necessarily need to get this training in a design school. You can do it by yourself. So, you can teach yourself all the material you need to know to become a successful designer.

But in the 21st century, we're moving to more and more complex problems that do require the talents of a designer. And these new kinds of problems are going to require new types of knowledge and new types of learning on the part of the designer. There you are – a great challenge. But that is the future of design. I want to talk about examples of what designers might be doing in the 21st century.

This post sheds further light on the benefits of generalists.

This Smashing Magazine piece examines an important aspect of Don Norman’s influence on design.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on The Secret of Don Norman's Success by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into The Secret of Don Norman's Success with our course Design for the 21st Century with Don Norman .

In this course, taught by your instructor, Don Norman, you’ll learn how designers can improve the world, how you can apply human-centered design to solve complex global challenges, and what 21st century skills you’ll need to make a difference in the world. Each lesson will build upon another to expand your knowledge of human-centered design and provide you with practical skills to make a difference in the world.

“The challenge is to use the principles of human-centered design to produce positive results, products that enhance lives and add to our pleasure and enjoyment. The goal is to produce a great product, one that is successful, and that customers love. It can be done.”

— Don Norman

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!