To improve the chances that your design will engage an audience, we must focus on how it can stand out. To do that, we need to know who our audience is. There’s no room for “everybody” when we’re targeting: far from it, so we split “cultural groups” into many divisions or co-cultures and aim at those instead. Once we know on whose devices our designs will appear, we can bring values framing into the picture, the technique we use to tap users’ underlying values to inspire them to achieve goals on our designs. We’re aiming to make our users persuade themselves by showing them a “mirror”. The more of themselves they recognize in a design, the more they’ll believe it and be likely to follow through with the actions they (and we) desire.

The Illusion of Culture—Lots of little Icebergs

Author/Copyright holder: Fotolia. Copyright terms and licence: All rights reserved Img source

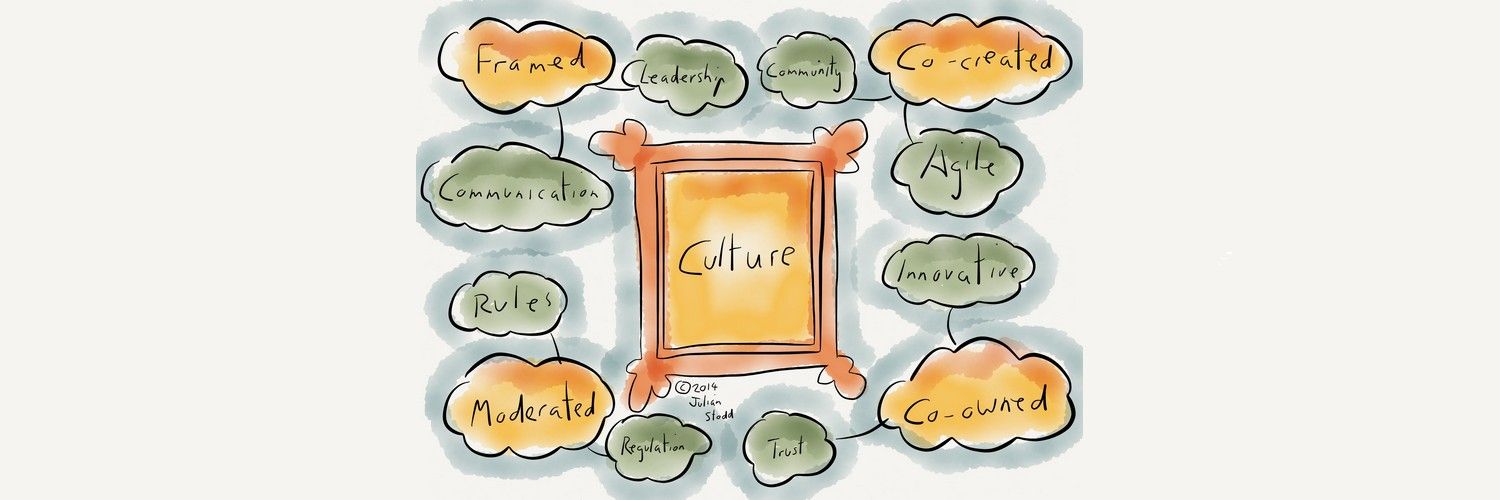

As the way of life of any given group, culture is a powerful force that shapes and defines people’s ways of seeing the world. It can be very visible, but can also exist in places we might not consider, such as office buildings and schools. Anywhere where a group of people interact and share the same language (including jargon and slang), values, norms, symbols, interests, etc., we can identify their group as one culture, or society. Culture is what has driven certain groups to attach different connotations to colors, for instance. Culture can also unite complete strangers, living thousands of miles apart. This can include people in different nations with different cultural views but sharing a hobby. We could, therefore, say that their common interest forms a smaller culture within their larger culture, or a “co-culture”. A drone enthusiast in Brazil and one in Denmark are united that way, for example. Or, such a term can include a group of people whose financial status has made them “first-time house buyers”.

Think of any nation…what imagery does that land’s name conjure for you? If you thought of China, you might envision pandas, the Great Wall, or red temples. One word—“China”—can convey many powerful notions of “China-ness”, or what we each might make of Chinese qualities. If we think harder, we might envision people in China, their language, dress, and cuisine. Doing so, we are face to face with the cultural iceberg, seeing only 10% of that society’s characteristics, not seeing the 90% of underlying elements, such as approaches to decision-making and concepts of self.

There’s a danger of oversimplification. If a company boss asked you to design for a “Chinese audience”, that would be too broad. For one thing, China is not monolithic; there are many groups, based on such factors as ethnicity, age, interests, and let’s not forget genders, among others. It may be populous, but not everywhere has the hustle and bustle of Shanghai. While the People’s Republic of China may appear to be harnessed as one powerhouse of an entity, the reality is that it, like any other country, is made up of many smaller cultures or co-cultures. People are people everywhere. As such, they will have interests and tastes that you can design for. You can’t design for a “Chinese person” or “a Briton”, for example, but you can for a Chinese software undergraduate who’s looking to apply to the British university that’s hired you to design an advertisement for their computer college that will be shown in China.

What exactly is Co-Culture and how do I get one?

A co-culture is a group whose values, beliefs or behaviors set it apart from the larger culture, which it is a part of and with which it shares many similarities. Cultures may comprise many subsets, and these co-cultures may thrive within them. For example, many world cities have a Chinatown. A student resident of London’s Chinatown might have a British passport, but he could be described as having a set of co-cultures, including Hong Kong parentage, bilingualism, being a business school student, drone enthusiast and a 20-something, living with parents.

We can draw up dividing lines within any society to isolate co-cultures using parameters such as age, gender, politico-social affiliation, lifestyle choice, socioeconomic level, ethnicity, education, region, language, and religion. We may all belong to the human species, and we may all be unique, but if you were asked to describe yourself in 20 adjectives, you would probably share these features with at least one other person on the planet.

Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede developed his cultural dimensions theory based on extensive observations of national behaviors. It is the framework for cross-cultural communication and key to noticing variations between cultural norms. Hofstede identified how societies around the world prioritize elements such as respect for authority, adaptability to change, whether they respect strength or sympathize with weakness, whether they are progressive or traditional, whether they value freedom to pursue happiness or view happiness as being determined by other factors, or whether they view the world through an individual or a collective lens. Of course, culture is more than just national identity. Corporations determine their own cultures that tend to transcend national boundaries. However, the way they present the goods and services that they offer to customers differs around the world. This is because, while universal human values are common to all, different nationalities place emphasis on different values.

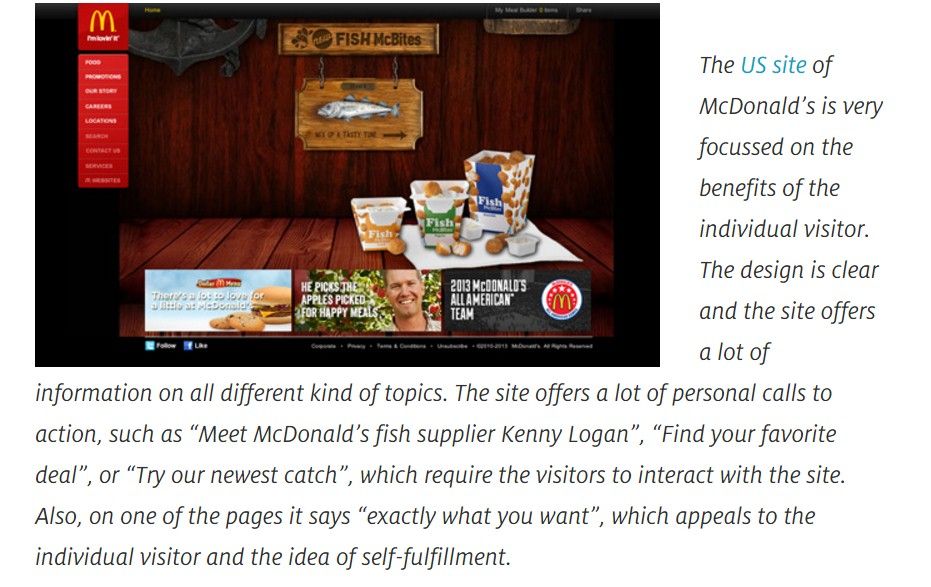

For example, one of Hofstede’s categories, individualism versus collectivism (IDV), is a major determinant in advertising. In individualist societies (such as those in the majority of Western nations), people tend to refer to themselves as “I” and “we” and prefer a social network where everyone takes care of himself/herself and the immediate family. In collectivist societies (such as Turkey, Mexico or Japan), individuals tend to focus on the group and community, prioritizing others, sometimes ahead of themselves, assuming that, because everyone else is doing that, everyone will look after everyone else, reciprocally. For example, McDonald’s advertises to its US audience by focusing on the individual visitor.

Author/Copyright holder: Usabilla Blog. Copyright terms and licence: All rights reserved Img Src

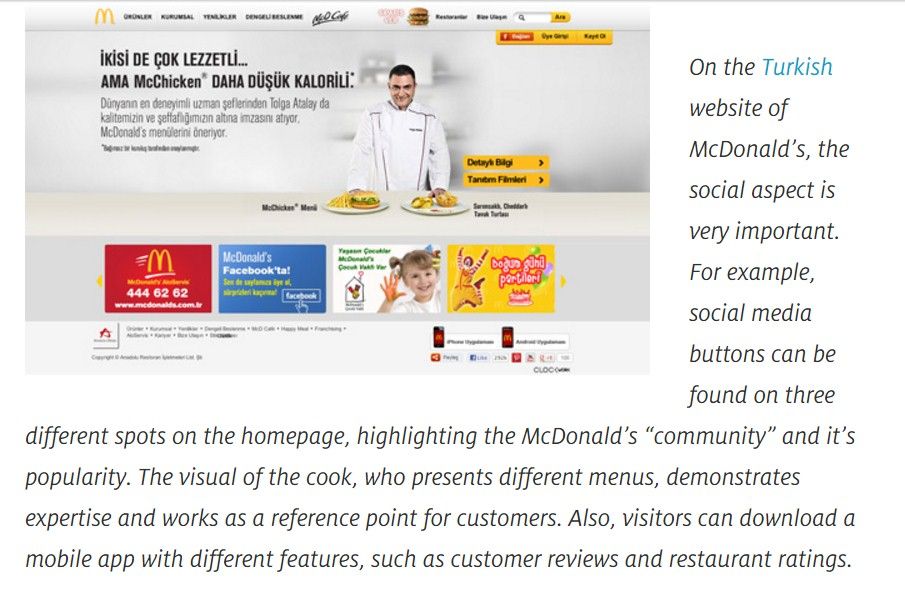

Whereas, in Turkey, the focus of the website is to show McDonald’s popularity.

Author/Copyright holder: Usabilla Blog. Copyright terms and licence: All rights reserved Img Src

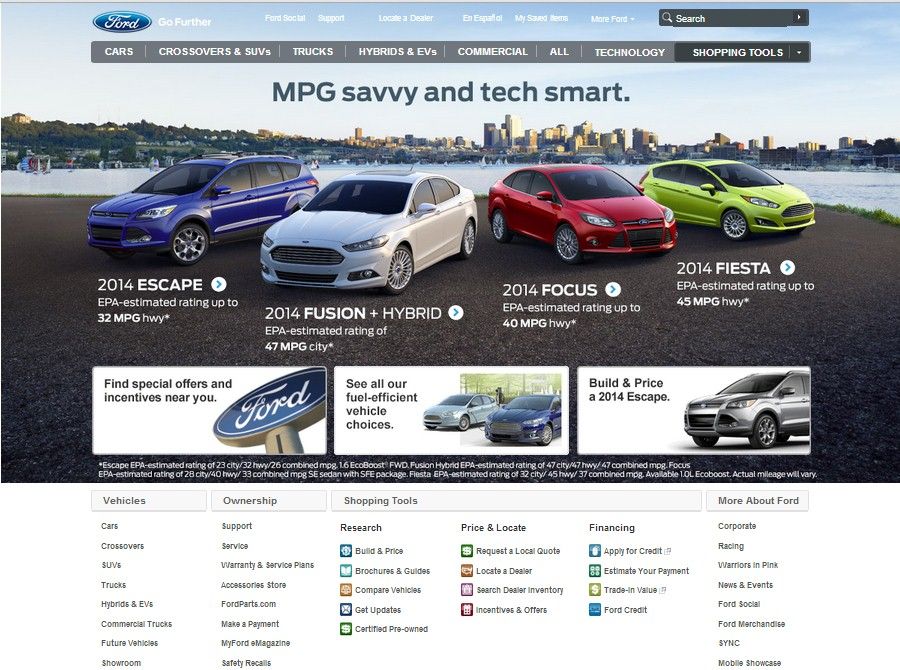

Or, we could take a car manufacturer, such as Ford, and plan our design for a domestic market. The image below shows a range of their vehicles that appeal to a certain co-culture of driver, specifically drivers in North America who have urban and commuter sensibilities.

Author/Copyright holder: Ford. Copyright terms and licence: Fair Use

Here, we can instantly picture a profile of the targeted sub-culture. It wouldn’t be people from rural areas, or young drivers in school or college. These are commuter vehicles, which appeal to a range of the population that commutes to work and specifically needs high-mileage, trustworthy vehicles. That co-culture has values to which Ford has appealed in this design.

If, on the other hand, we wanted to think of pickup trucks, we might imagine a driver in a rural area, Jerry, who:

1) Is American

2) Lives in a town of 1,000 people

3) Listens to country music

4) Transports a lot of heavy farm materials.

5) Uses an iPhone

6) Likes beer

7) Is an ex-smoker

8) Was in the Army

9) Never went to university

10) Has a $50,000 mortgage.

Jerry lives in a small town. His neighbor is a retired university professor from Los Angeles, Helen, who always wanted to live in the country. Helen drives a classic Volkswagen Beetle. She:

1) Is American

2) Lives in a rural small town

3) Listens to classical music

4) Transports little, except for library books and groceries

5) Has an old flip-top phone.

6) Likes drinking coffee

7) Has never smoked

8) Was an academic, never working elsewhere

9) Has two doctorates – history and philosophy.

10) Owns her home outright.

People living on the same street, even in the same house can belong to many different co-cultures. Teenagers may live under the same roof as their parents, and share many cultural characteristics. However, when it comes to musical taste, dress sense, and attitudes towards authority, there are bound to be differences. Just because, for example, Mr. Smithson likes this sort of car or that sort of food is no guarantee that his wife will. Neither approves of their 16-year-old son’s loud industrial music, his ear-piercing, and his outlandish hairstyle that they think might keep him from finding a “proper” job.

As we can see, co-cultures may show a lot of dividing lines; however, those different values and tastes also link people across the world. One person “consists” of many co-cultures, and every person belongs to many co-cultures at the same time and has the same basic values and viewpoints as others in their categories.

Targeting your intended audience

Whatever your organization’s message is, you as the designer have to have these different co-cultures firmly in mind as you design. Our users are so much more than ‘people’. Cultural theorist Stuart Hall has explored and discussed the global social hierarchy, and a wealth of information exists about such considerations. One of Hall’s most important observations is that, “a message must be perceived as meaningful discourse and be meaningfully de-coded before it has an effect, a use, or satisfies a need.” The success of a design, therefore, depends on its ability to be received by the usership, who can “de-code” it and react with approval.

Values Framing

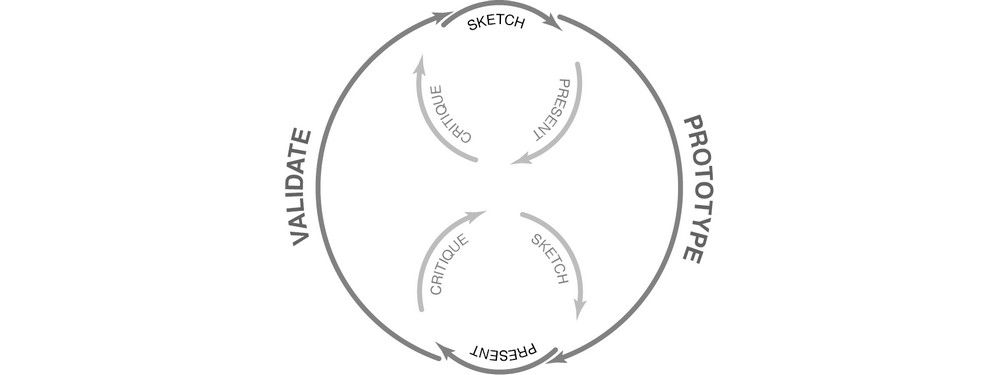

Milton Rokeach, a renowned values researcher, submitted, “Value hierarchies or priorities are organizations of values enabling us to choose between alternative goals and actions, and enabling to resolve conflict” (Rockeach, 1979). So, when we are defining our target audience, we can work on our message so that it will appeal best to the value they likely hold as a certain priority. Mirroring our target co-cultures’ values, the design we make will be particularly effective in persuading them, because it will have accessed them at a certain level.

Our values come from our environment largely during our adolescent years, shaped by parents, teachers and friends, among other influences. These tend to “solidify” and remain stable throughout our lifetimes. Values framing refers to the art of presenting information so that it reflects certain values. We may not notice, but it is already all around us. The general type of values framing is obvious to us anytime we go into a store and see a price tag. One universally human value is the desire to save money, or at least not to waste it. One cent is the difference between $1 and $0.99, but psychologists have known for many years that shoppers are more likely to persuade themselves to buy something if it appears to cost less. Our eyes may show us the “99”, but they reassure us that the “0.”is better than a “1”.

If you turn on the TV and a show you don’t like is on, you turn the channel. That’s values framing right there. When you stop at a TV show that you do like, you may be too busy enjoying yourself to realize that the production company has accessed your tastes, and has framed your values. In other words, the show reflects your values, and you may notice that the studio also has another series that’s based on one of the characters. Let’s consider a hypothetical sitcom, featuring a likeable young San Francisco executive, Trif, who lives next door to his aging hippie parents, whose pet jellyfish he has agreed to care for. He tries to balance his eccentric, colorful background with a corporate job, trying to make sure that his boss and the girl he likes at work don’t find out about his hippie origins (hence, why he’s a spineless jellyfish, just like his pet, even if he’s a nice guy). Something about “My Pet Jellyfish” speaks to you; you may live in a big city, in a small apartment, like the lead characters, and you may understand how hard it can be to show and celebrate individuality in a corporate culture. You may like gritty humor and the point that the central character has a quirky neighbor who mistakenly thinks that his having a pet jellyfish means that he follows the Pastafarian religion.

Let’s remember that we’re also designing to win the trust of our targeted users. You need to portray a credible image for your organization. A good-looking, easy-to-use design that conforms to what users expect to see will keep them on “the same page” as you. Good! Now we can focus on increasing our users’ sense of familiarity and build their belief that we are just like them. This is like polishing the “mirror” so they see themselves (i.e., their values) perfectly in it.

Let’s go back to the Smithson household and look at an example of how we might target a design. Jimmy, 16, wants to be a DJ when he leaves school. His friends have just told him about an app you can download that works out really powerful playlist sequences. Jimmy knows that the most successful DJs order their tracks to maximize impact.

By some strange coincidence, you’re the designer of that app: 3-6-0-Scratch! You know you’ll have to persuade users such as Jimmy to try it (and, hopefully, buy it!). Knowing that DJs (aspiring, amateur and professional!) tend to be males, aged15-30 has given you a great start in your design. Let’s look at what’s involved in this act of persuasion. Taking Aristotle’s three appeals, logos (the facts), pathos (the emotions), and ethos (our identity as the honest voice of the organization), we have:

1. Logos—you mention the point that your app accesses the largest track libraries faster than anything else available.

2. Pathos—you use the text and images to show users like Jimmy that he needs this if he wants his career to take off. “3-6-0-Scratch gets you from the garage to the mirage. Join 5,000 DJs who have given us 5-star reviews!”

3. Ethos—Quick, this is where you get street cred. Are you going to approach a famous DJ? If a famous industry name is on your site, thereby endorsing the app, you’ll be so many more steps closer to winning over users like Jimmy.

The result? Jimmy realizes that this app is like gold dust; he’s clicked on the trial and, because it’s affordable to buy, he probably will. Congratulations on having framed his values. Because you “speak” his “language”, have shown how much you’re in tune with his world, and because he trusts and likes what he sees, you’ve managed to persuade Jimmy to persuade himself. He’s been on many DJing sites, but yours struck a chord in him, not least because you offer a free trial, provide a weekly newsletter and have a cool DJ “gorilla” in the corner of the screen playing random samples.

You’ve never met Jimmy, but your design achieved such presence that he forgot he was looking at an app on a site over the Internet. You captivated him to the point where the app became a must-have tool.

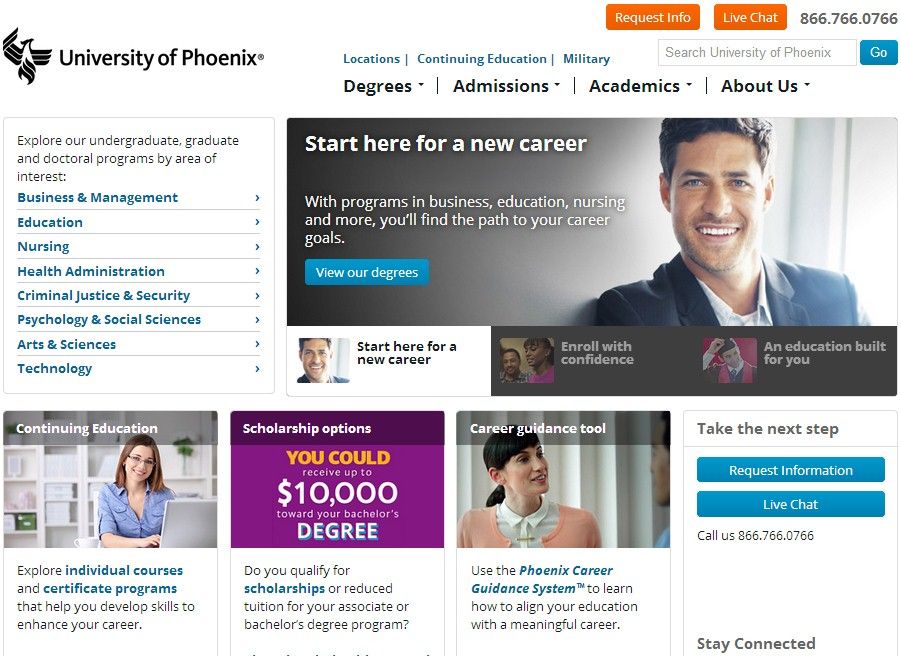

Let’s look at a design that’s already been made. For example, this landing page, below, for the University of Phoenix is fine-tuned to appeal to a co-culture. Unlike many universities (which focus on education as a means and end in itself), Phoenix places emphasis on the point that getting a degree is the means to another, very visible end (career).

Author/Copyright holder: University of Phoenix. Copyright terms and licence: Fair Use.

This design casts out to reach mid-career, working people, aged 30s-50s, who want to advance in their careers. Middle-class, they will be likely to favor this university because it is close to where they live and work; they won’t be able to travel to UCLA in Los Angeles. Therefore, this co-culture is primarily determined by socioeconomics, income bracket, age (i.e., period in working life), educational background, and region.

Mathew Nesbit, a professor at Northeastern University determined: “There is no such thing as unframed information, and most successful communicators are adept at framing.” Designers use words, images, metaphors, comparisons and presentation styles to communicate their organization’s message to users. Knowing the audience means that we can frame the message, or design, for greater impact and appeal. Also, being aware of the nature of the organization you’re designing for is key. Some industries allow you to inject life and color into a design. Others, such as a bank offering mortgages, require a more restrained approach. For instance, there, potential borrowers just want the facts about what percent of APR you’re offering, so you’d want to frame some simple text to show them that clearly. Values framing design involves meeting your co-culture (the targeted audience) with messages that access them quickly, and in a way that they’ll believe that you know them intimately enough to trust your organization and what you’re offering, and they’ll proceed to a call to action.

The Take Away

Co-cultures are subsets of larger cultures, sharing similar features with the larger cultures of which they are a part. Cultures define a group of people sharing a common language, religion, notions about community, etc.; co-cultures are more complex. Each user carries several co-cultures by being from an ethnic group, a language group, an age group, an interest (politics, music, cuisine, etc.) group and more. So, there are a wide variety of target audiences for whatever service, product or message our organization is offering.

Understanding how culture defines groups is an important start to understanding co-cultures. Human values are universal, but the order in which societies prioritize these elements differs. Generalizing is valid because designers can tailor a UX design to a predictable market, once they have identified that target audience as a co-culture.

Overall, we establish a path toward persuading users that we know what they want because we’re one of them. In that sense, there’s a mirror in the values frame that we hold up so that wherever the target audience is, they’ll believe what we’re saying; better still, there’s a better chance that they’ll like what we’re showing them and follow through with a call to action.

Where to Learn More

Yocco, V. (2014).“Framing Effective Messages to Motivate Your Users”. Travis, D. Smashing Magazine.

Travis, D. (2010). “Persuasion Triggers In Web Design”. Smashing Magazine.

Baxi, K. (2015). “UX and Culture: Bridging the Gap in Six Strides”.

Hero Image: Author/Copyright holder: Julian Stodd. Copyright terms and licence: All rights reserved.Img