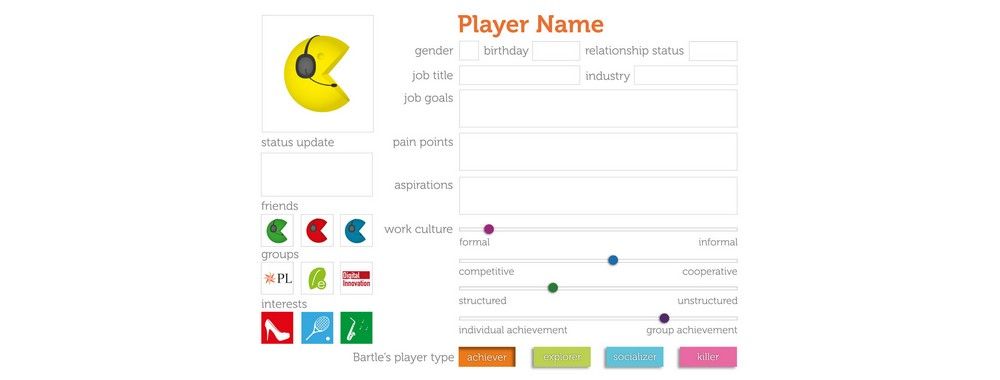

We’ve all come to think in terms of user-centred design over the years. It’s a critical component of UX design, and it helps us focus on what really matters when developing products. However, user-centred design is not enough for gamification. Here, we introduce the concept of player-centred design, which takes the idea of user-centred design to the next level.

Coping with Change

What was the first computer game you ever played? If you’re starting to enter middle age, it’s likely to have been something like Space Invaders or Pacman. How do those games stack up next to modern classics such as Grand Theft Auto or World of Warcraft? There’s a huge difference between them, isn’t there? Space Invaders may have seemed incredible when it was released in 1978; today, it looks kind of… well, basic and uninteresting. We won’t be uncharitable, as it’s hardly fair to compare something that came so much later, but the principle is true all the same.

Game play has changed, too, from ‘move left, move right and fire’ to being able to carry out incredibly complex actions. Indeed, what hasn’t changed is certainly the adrenalin rush players can feel. In the late ‘70s, that would have translated to the dread (yes, still a form of entertainment) a player would have felt on seeing the last invader of a screen speed up and strafe rockets in ultra-dangerous motions (if you’ve never played Space Invaders, you need to give it a go). Hold that thought—now transpose it upon any game you may have played in the early 21st century. The principles of entertainment and satisfaction, of “Yes!” on clearing a skill level and “Oh, sh*t!” on not making it are common to these games. Still, the differences are powerful, so we have to cope with a whole different set of dimensions in the 21st century.

Pacman was one of the earliest popular computer games, and while it’s still fun, today’s games are far more complex and engaging. That said, why not go retro for a moment and see what these games have in common—or maybe that should be, feel what they share. If you’re thinking the “Yes!” feeling on clearing a level and the “Oh, sh*t!” sensation on getting killed, you’ve got a hole in one.

© Unknown, Unknown

Player-Centred Design

Let’s kick off this topic by remembering that in any game, a fair degree of work is involved. From that, in the gamification of a work process, getting the user to want to take part in that work is vital.

"Games give us unnecessary obstacles that we volunteer to tackle."

— Jane McGonigal, American game designer and author

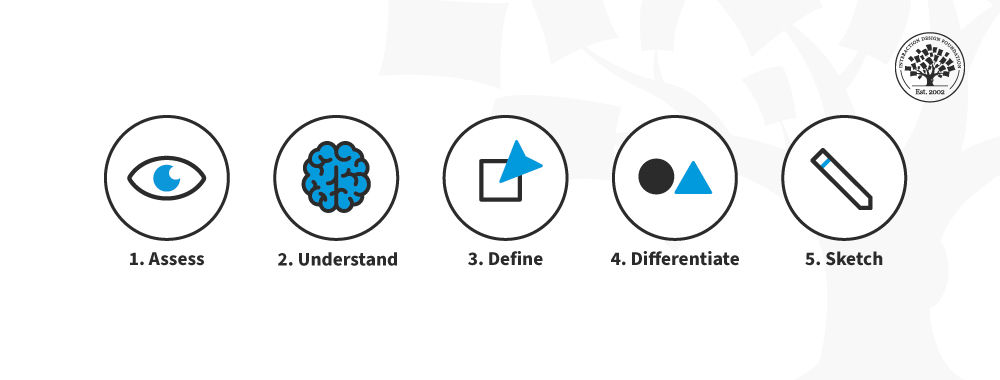

Player-centred design builds on and extends user-centred design to a whole new level; it is a process that Janaki Kumar and Mario Herger coined in their book, Gamification at Work: Designing Engaging Business Software. We can use user-centred design to develop applications as much as we can to develop games. Player-centred design acknowledges that a game is to be played and looks at the key ingredients of making a game work for the player. You can see those elements on the diagram at the very start.

Yes, player-centred design is a powerful ally; still, you need to place it as a process into the context of your organization. It’s not meant to be a rigid framework for you to adhere to at all costs; rather, it’s been developed to enable you to adapt the framework to your people and your business. Missions, mechanics and motivations can vary widely; therefore, it’s vital to ensure that they match the organizational and individual player needs you’re targeting for them to be successful.

This scene from Farcry shows just how much games were to evolve since Pacman. Incidentally, they can only get ‘realer’.

© BagoGames, CC BY 2.0

Player-centred design is also an iterative process. That means developing something, trialing it with players, and then amending it until it hits the sweet spot where players really appreciate a specific feature. That’s why monitoring, measuring and managing are a key part of the framework. That’s why these three ‘m’s must be centremost in your mind when you sit down to apply this powerful tool in your own work.

The final part of player-centred design is balancing legal and ethical considerations and business requirements with keeping the whole thing fun. Gamification needs to meet all those requirements in order for you to make a success of the process via what end result you present to your end user.

User-centred design uses the yardsticks of efficiency, effectiveness and satisfaction to evaluate designs. Player-centred design adds engagement to this list. While user-centred design asks the question, “Can the user use the product efficiently, effectively and satisfactorily?”, player-centred design asks, “Do they want to use it in the first place?”.

Take a classic example in the workplace: getting employees to complete e-learning modules. Bear in mind that these are often geared towards satisfying company requirements (such as covering their backs vis-à-vis legislation regarding disability, gender equality, etc.) as opposed to offering staff members vocation-specific advancement. Organisations frequently approach designers when they want us to crank out the finest e-learning guides to a wide range of topics, such as ethics, diversity and data security protocols, perhaps without realising how golden an opportunity we might have there—that is, we can actually make those workers want to complete their e-learning!

Traditionally, getting workers to read S.O.P.s (Standard Operating Procedures) has been like pulling teeth for most Western organisations. If you can remember working in the previous century, you may well recall these—a printout of clauses in semi-legalese that you had sign off at the bottom so as to show you understood that, for example, standing beneath a forklift’s prongs while it’s lifting down a palette would be an exceptionally poor idea. With the advent of the internet, e-learning would make the whole process electronic. After all, what better opportunity is there for you as a designer than to work player-centred design into an otherwise dead and dry piece an employee would probably only pretend to read? If you can produce, say, a design for an e-learning module on diversity that encourages users to learn more about cultures by whetting their appetites to learn and enjoy the experience, you’re thinking player-centred—congratulations. They could move around a virtual globe, say, picking up ‘passport’ points, the idea being that while they’re learning all about cultural diversity, they’re enjoying the experience and feeling empowered. Hopefully, they’ll have forgotten that the organisation actually had the power over them to make them take the e-learning. Such is the magic a skillfully devised player-centred design can work.

As you can see, when people truly embrace gaming, they’re prepared to go to extraordinary lengths to participate.

© Sergey Galyonkin, CC BY-SA 2.0

Kumar and Herger offer sound advice for us as we ponder these questions: “Gamification is about thoughtful introduction of gamification techniques that engage your users. Gamification is not about manipulating your users, but about motivating them. Ultimately, it is about good design — and good design treats the user with respect.” Here, we can cast our minds back to one of the most fundamental points about fun: you can never force or trick someone into having it; people will either have fun as a natural reaction to what you provide… or they won’t. And if they make fun of it, then that can be rather worrying.

The Take Away

Player-centred design is an extension of the idea of user-centred design. It applies uniquely to gamification design within systems which traditionally do not contain game elements. It looks at the users and asks the key question, “Do they want to use this in the first instance?”. It allows you to adapt gamification to the needs of your users and ensure that the results of the exercise support the business reasons for gamification. If you can weave player-centred design into the exact context of your audience’s organisation, you will travel a long way in starting to deliver a piece that not only gets results but one that also is popular.

References & Where to Learn More

Janaki Mythily Kumar and Mario Herger, Gamification at Work: Designing Engaging Business Software, The Interaction Design Foundation, 2014

Hero Image: © Janaki Kumar and Mario Herger, CC-Att-ND