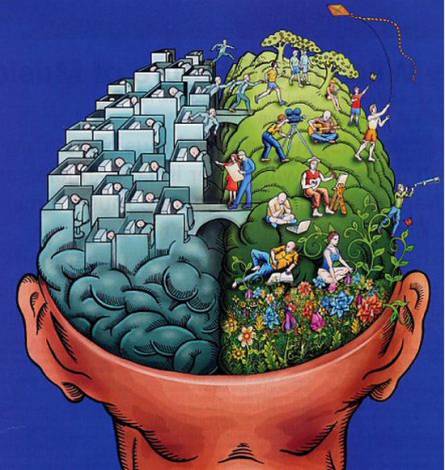

When we think of improving performance in any area of our lives, we tend to focus on activities directly related to that particular area. If a chef wants to get better at chopping vegetables into neat Juliennes, they will just keep chopping until they perfect the skill. If an author wants to improve their characterisation, they might go out and speak to people and build up character profiles based on their research. If a shop keeper wants to calculate the amount of change they must give customers, they might practice their basic mental arithmetic.

Focussed activities, such as those listed above, obviously help improve performance, but our readiness and mental focus has a significant part to play in the rate we make these improvements. When we are not concentrating, practice doesn’t tend to stick, as improvements are based on the gradual insights and subtle advances we make when focussed on the actions and thought processes involved.

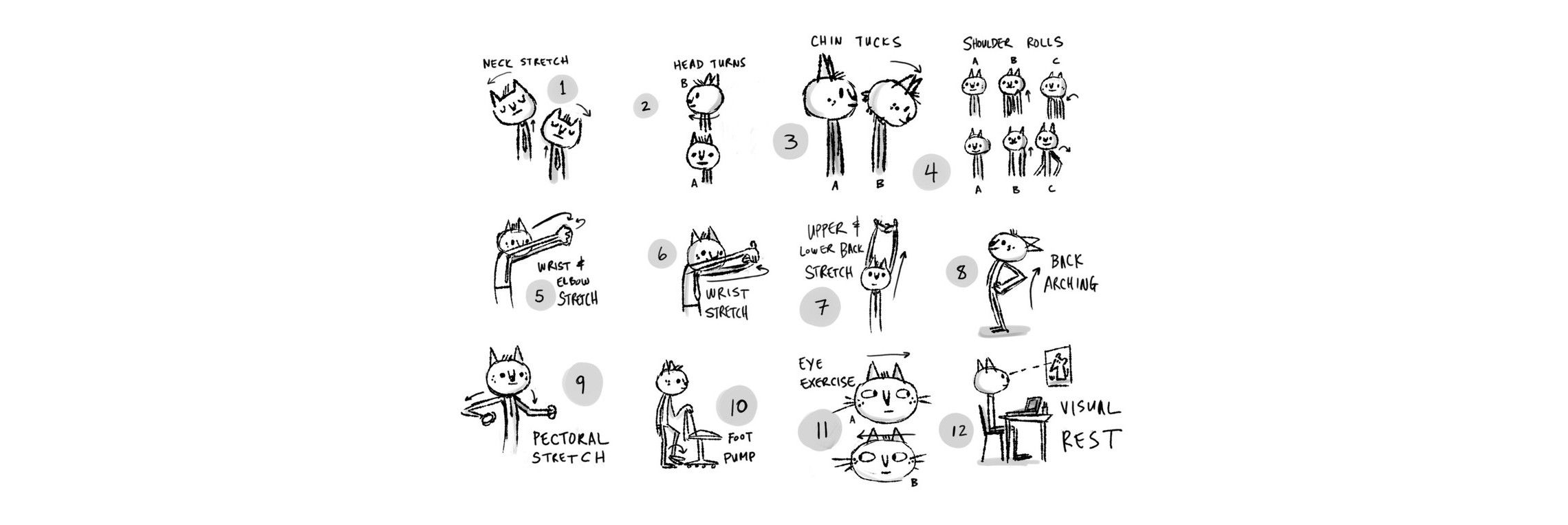

Author/Copyright holder: Sacha Chua. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY 2.0

Mental preparedness is an essential aspect of all human action. Unless we have the motivation, drive, and necessary focus, performance suffers, and we are inclined to commit errors and perform poorly overall. For this reason, mental preparedness is a growing area for research, and one particular aspect of this is the effect of physical exercise on work performance.

Research into Mental Performance and Physical Exercise

Hogan, Mata, and Carstensen (2013) tested young and older adults following 15 minutes of moderate exercise on a stationary bike, and found significantly higher performance levels on working memory tasks. They also found that levels of positive affect (i.e. positive emotional experience) increased for those subjects in the experimental (i.e. moderate exercise) condition.

Author/Copyright holder: Sacha Chua. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY 2.0

McKenna, Coulson, and Field (2008) collected self-reports from white-collar employees in Bristol, UK. These employees were specifically selected on the basis that they used on-site exercise facilities during workdays. McKenna et al asked participants to fill out questionnaires to report work performance, physical activity, and fill out mood diaries, which were used to measure how active or sedentary their job was. The major findings from this study were as follows:

- Self-directed exercise seemed to predict important mood benefits.

- The participants, all of which were engaging in either ‘moderate-to-vigorous’ or ‘very hard’ exercise, demonstrated improved workplace performance.

- Exercise at work was also associated with mood benefits in regards to how these employees viewed themselves, their tasks and their colleagues.

- Lastly, “...self-reported performance improvements were largely dependent of exercise-related mood changes”.

Collectively these findings give strong support to the practice of exercising at work, as a means of boosting mood, team morale, and work performance.

Ron Friedman (2014) recommends a number of things to help incorporate exercise into your everyday routine to boost work performance and morale:

- Identify a physical activity you actually like – This might seem obvious at first, but so often we view exercise as a chore, which is exactly what puts us of in the first place. If you think of something you actually might like to do, it won’t seem such a chore. For example, playing a team sport like netball, ‘soccer’, or basketball can make things seem less like exercise.

- Invest in improving your performance – Set goals for your exercise routine. It is difficult to stick to something unless you have a clear aim in mind, and more specifically, these goals should be aimed at mastering a skill, rather than directed at performance levels. Research, such as Rawsthorne and Elliot (1999), shows that establishing mastery goals (i.e. those based on achieving new levels of competence) improve intrinsic motivation more so than performance-based goals.

- Become part of a group, not a collective – There is a distinction between joining a group and a collective; a group is something we play an important part in, while a collective is something that exists whether you are involved or not. For example, team-based sports are dependent on each of its members turning up and taking parting, but a Zumba fitness class will be unaffected by your presence or absence. When people depend upon you, there is a sense of belonging and social aspects of the exercise are based on your involvement, which, research suggests, makes people less likely to quit an activity.

In Summary

Exercise can be a good way to clear your head and let off some steam. It can also help improve your mood, work performance, and your relations with colleagues; especially, if you exercise at work, it would appear. So dust off your old football boots/sneakers/tennis racket/cricket bat/sweat band and set yourself some ‘mastery goals’.

Header Image: Author/Copyright holder: Unknown. Copyright terms and licence: Unknown. Img