"Game Mechanics are constructs of rules and feedback loops intended to produce enjoyable gameplay. They are the building blocks that can be applied and combined to gamify any non-game context."

— The Gamification WIKI

Mechanics are the most visible part of gamification and tend to be the primary focus of most gamification projects. We like to think of game mechanics as paints in an artist's palette. We cannot create great art just by adding many colors to our picture, unless we also have an artistic vision, talent, and training to begin with. Similarly, successful application of game mechanics depends on a well-designed gamification strategy built on a good understanding of the player, the mission, and human motivation.

In this chapter, we present a curated list of game mechanics that may be used as building blocks and combined in strategic ways to achieve the positive engagement loop in your application.

6.1 Curated list of Game Mechanics

Courtesy of Janaki Kumar and Mario Herger. Copyright: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported).

Courtesy of Janaki Kumar and Mario Herger. Copyright: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported). Figure 6.1: The Tag cloud of game mechanics

There are a few collections of game mechanics available online (footnote 1). We find these lists are at different levels of granularity and not all of them are pertinent to enterprise gamification. Therefore, we have curated a list of game mechanics that can help business software designers embark on their gamification journey.

When used appropriately, game mechanics can leverage a natural motivational driver in the player. For example, the motivation driver for collection may be addressed with badges, and the achievement motivation may be addressed by leaderboard. However, in a holistic gamification design, many motivational drivers may be at play. For example, FourSquare players may be motivated by collecting points and badges, achieving the status of mayor in their favorite establishment and connecting with their network while doing so. We will point out the primary motivational driver addressed by each of the game mechanics discussed below.

6.1.1 Points

Points are the granular units of measurement in gamification. They are single count metrics. This is the way the system keeps count of the player's actions pertaining to the targeted behaviors in the overall gamification strategy. For example, FourSquare counts each check in, and LinkedIn counts each connection.

Points provide instant feedback to the player, and thus address the feedback motivational driver. Players may also motivated by collection, to see their points count go up.

Figure 6.2: Foursquare gives points for each check-in

Figure 6.3: LinkedIn counts each connection

6.1.2 Badges

Once the players have accumulated a certain number of points, they may be awarded badges. Badges are a form of virtual achievement by the player. They provide positive reinforcement for the targeted behavior.

Foursquare awards badges when the player has accumulated enough check-ins. Another example of a badge is eBay's top seller virtual "ribbon".

Badges address the motivational driver of collection and achievement.

Figure 6.4: Foursquare awards badges

Figure 6.5: eBay awards a top seller virtual ribbon

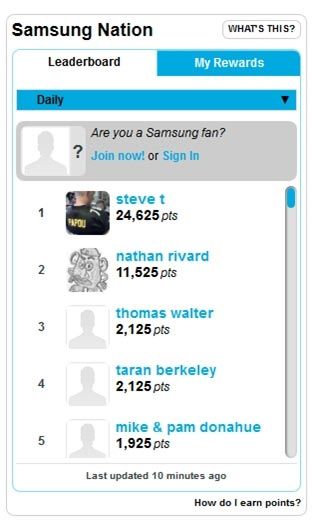

6.1.3 Leaderboards

Leaderboards bring in the social aspect of points and badges, by displaying the players on a list, typically ranked in descending order with the greatest number of points at the top. The possible disadvantage of a leaderboard is that it could be demotivating to a new player. For example, if player A has 10,000 points, and is on top of the leaderboard, and a new player B has 10 points and is at the bottom, it is likely that player B may become demotivated and give up playing the game. She, or he, may believe that he/she is never going to compete with player A, and therefore why should he/she even try?

Figure 6.6: Samsung Nation leaderboard

Foursquare has a leaderboard modified into a cross-situational leader board. This variant places the logged-in player (Matt Healy in Figure 6.7) in the center and shows similar scoring fellow players above (Tristan Walker) and below (Tim Vetter) for context. The ranking (points) is limited to a set of players who are close to the logged-in player. The goal with this variant of leaderboard is to motivate the player to compete with the players closest to him. Note that a cross-situational leaderboard may be different for each player since it is limited to his or her context. It does not convey an overall ranking of all players.

The achievement motivational driver is addressed via a leaderboard.

Figure 6.7: Cross-situational leaderboard by Foursquare

6.1.4 Relationships

Relationships are game mechanics based on the motivational driver of connection. We are social beings, and relationships have a powerful effect on how we feel and what we do.

Peer pressure is not restricted to school-age children. Adults succumb to it too. In 2010, one of the authors (Janaki Kumar) did research on personal sustainability and one of the findings was that a trusted person in a participant's network had more impact on his or her day-to-day choices than the media. For example, participants were more likely to recycle if a trusted member of their community did so, than if they were told to do so by the media.

Relationships reduce stress in people and are positive motivators. People who are trying to quit bad habits such as alcoholism, or deal with a loss of a loved one have found that support groups offer emotional support and encouragement during a time of need. In the technology world, developer communities are a good example of a support group for developers where they offer and receive technical help.

Relationship addresses the motivational driver of connection.

Figure 6.8: Twitter urges me to follow John Maeda and IxDA since people in my current network do so

6.1.5 Challenge (with epic meaning)

Challenge is a powerful game mechanic to motivate people to action, especially if they believe they are working to achieve something great, something awe-inspiring, and something bigger than themselves.

As we mentioned earlier, scientist at the University of Washington challenged the public to play Foldit (footnote 2), a game about protein folding. This game has a scientific purpose behind it. Knowing the structure of the protein in a cell was the key to understanding how it works and how to target it with drugs. Since proteins are part of so many diseases, they can also be part of the cure. Folding proteins provides important clues to the scientists on how to prevent or treat diseases such as HIV/AIDS, cancer and Alzheimer's. A team of experts had worked on this problem for over 10 years and had not solved it. Once the scientific challenge was launched in the form of a game, 46,000 volunteer players solved the puzzle in 10 days.

The challenge game mechanic addresses the achievement motivational driver. However, in the case of the Foldit challenge, the feeling of connection and perhaps reciprocity, (if the player had known someone dear to him/her suffering with the illness the challenge was seeking to cure) may have played a part in its overwhelming success.

Copyright © Foldit. All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine. See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "fairUse") of the copyright notice.

Copyright © Foldit. All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine. See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "fairUse") of the copyright notice. Figure 6.9: Foldit, a scientific challenge to citizen scientists that yielded spectacular results

6.1.6 Constraints (with urgent optimism)

Interestingly, constraints such as deadlines, when combined with urgent optimism, motivate people to action. Urgent Optimism (footnote 3) refers to extreme self-motivation. It is the desire to act immediately to tackle an obstacle combined with the belief that we have a reasonable hope of success.

Some registration sites use gamification to reduce the drop off rate by limiting the amount of time the user can take to complete the registration process.

Figure 6.10: There are only 11 minutes and 19 seconds to register. Better hurry!

Gilt, a fashion ecommerce site, constrains the time allowed for their customers to bid on items to motivate them to action.

Players are motivated by achievement when they are faced with these constraints and are driven to overcome them.

Figure 6.11: This GILT offer Ends Wed 03/24 Midnight EST. Act now!

6.1.7 Journey

The journey game mechanic recognizes that the player is on a personal journey and incorporates this element into the experience. Here are three examples of implementations of this game mechanic:

6.1.7.1 Onboarding

A new player needs to be on boarded since they are just starting the journey. Offering help and a brief introduction to the features and functions motivate the player to embark on the journey.

6.1.7.2 Scaffolding

Scaffolding is a way to help the on boarded, yet inexperienced, user avoid errors and feel a sense of positive accomplishment. A product could progressively disclose more features as the player gains more experience using the product.

6.1.7.3 Progress

Progress refers to providing feedback to the user on where he or she is in the journey, and encouraging him/her to take the next step.

Figure 6.12: LinkedIn uses Progress game mechanic to show that the player's profile is 90% complete and offers suggested next steps.

Journey addresses the player's need for blissful productivity, by presenting the right set of features appropriate to the player's level in the game.

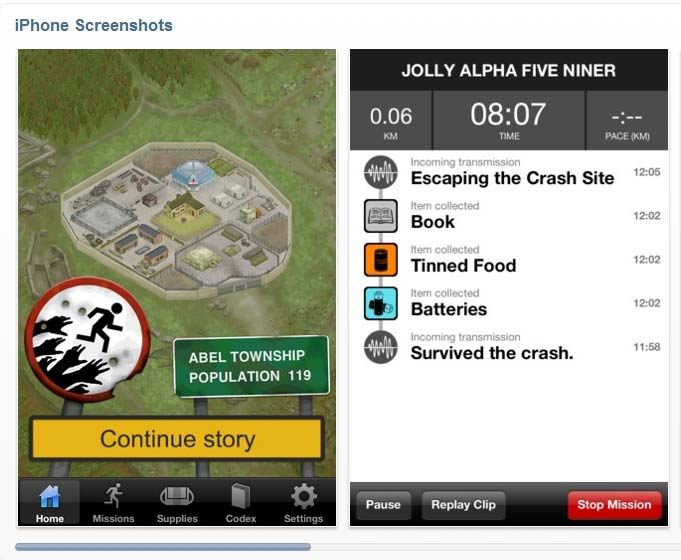

6.1.8 Narrative

The narrative game mechanic draws the players into a story within the game. Zombie Run, a fitness game, uses narrative to make the players believe that zombies are after them, and they need to run as fast as they can to get away. The object of the game is to motivate the players to get fit without making it explicit.

Figure 6.13: Zombies are after you. Run!

Narrative offers the players a chance to express themselves via role-play. In the case of Zombie run, players are motivated by achievement by out-running the zombies.

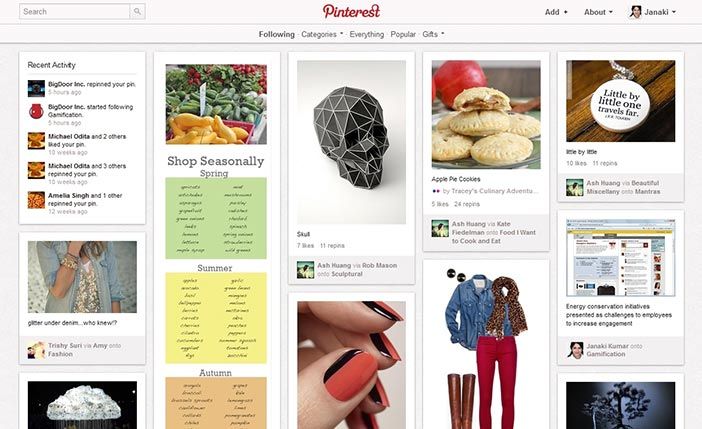

6.1.9 Emotion

As Don Norman eloquently argues in his book Emotional Design (footnote 4), our emotions do play a role in how we experience a product.

In many ways, emotional design is a large category in and of itself. In the context of gamification, we are not attempting to cover the topic as a whole. Rather, we want to draw inspiration from it, to enrich our gamification designs.

Game designers have led the way in investing in high quality artwork in their products that appeal to our emotions. Consumer products (iPhones, iPads) and websites (Pinterest) are following this trend. Employees experience emotional delight in the consumer software they use, and have similar expectations with enterprise software.

Copyright © Pinterest. All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine. See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "fairUse") of the copyright notice.

Copyright © Pinterest. All Rights Reserved. Used without permission under the Fair Use Doctrine. See the "Exceptions" section (and subsection "fairUse") of the copyright notice. Figure 6.14: Aesthetics in visual design

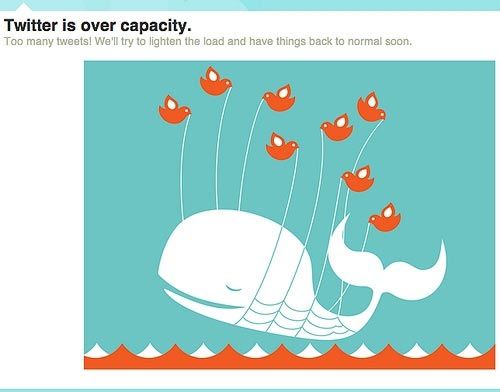

Humor is another emotion pertinent to game mechanics. The tone of the product can be conveyed in the micro-copy, or in the informational text and messages on the user interfaces. Humor has the power to deflect a negative experience into a (somewhat) positive one.

Humorous micro-copy addresses the motivational driver of feedback, while people may choose to use esthetically pleasing designed products as an avenue of self-expression.

Figure 6.15: Twitter fail whale. Their website is down, and instead of being annoyed, we smile.

6.2 The Game Plan

With a solid understanding of the player, mission, and motivation, the gamification system may be designed using game mechanics as building blocks. The three main considerations in pulling together the game plan are the game economy, game rules, engagement loops.

6.2.1 Game Economy

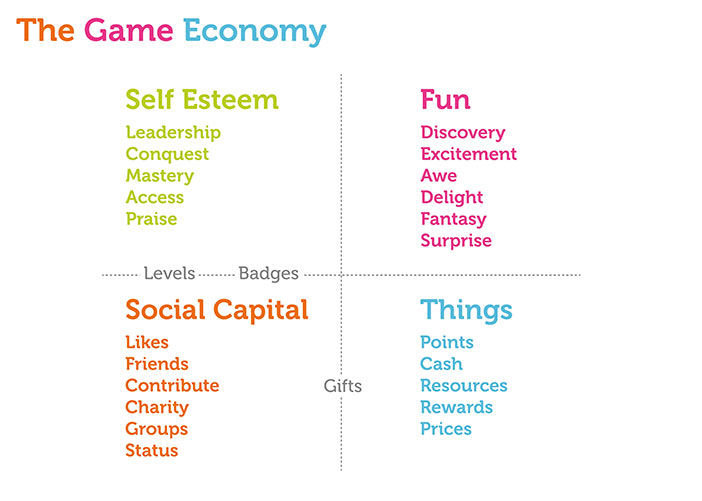

Garner describes game economy as follows:

There are four basic currencies that players accumulate in game economies — fun, things, social capital and self-esteem — that are implemented through game mechanics, such as points, badges and leaderboards. These game mechanics are simply tokens of different currencies of motivation that are being applied to reward players.

Courtesy of Janaki Kumar and Mario Herger. Copyright: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported).

Courtesy of Janaki Kumar and Mario Herger. Copyright: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported). Figure 6.16: Game Economy

Fun refers to rewards such as discovery, excitement, fantasy, awe, delight, and surprise. Things refer to cash, resources, and prizes or gifts. Social capital refers to likes, friends, and status. Self-esteem refers to praise, access, mastery, and conquest.

As part of the game plan, you can decide the mechanics you want to use as currencies in your game economy.

6.2.2 Game Rules

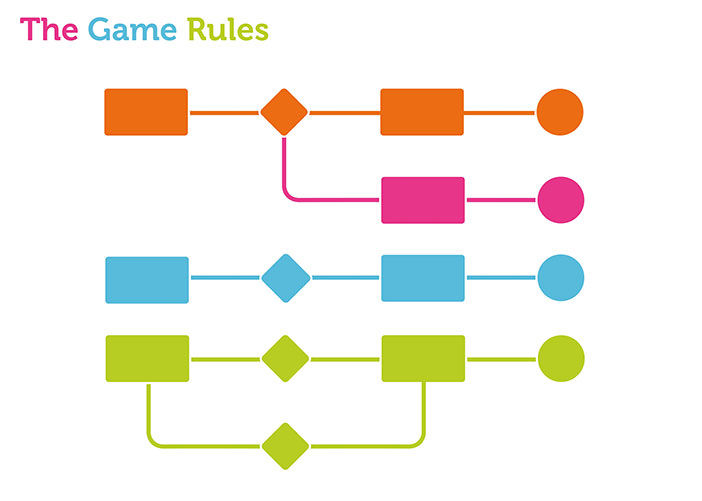

Once you have decided what mechanics to use, the next thing is to come up with a set of rules of the game. If you are designing a system to motivate call center employees to undergo training, and you have decided to use points in your game economy, you will need to decide how many points you award for the action. If the employee only took 50% of the training, do they receive all the points, none of the points, or 50% of the points?

Courtesy of Janaki Kumar and Mario Herger. Copyright: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported).

Courtesy of Janaki Kumar and Mario Herger. Copyright: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported). Figure 6.17: Game Rules

If you are designing a community where you are trying to increase participation, do you award points for all comments, or only for thoughtful comments, and who decides if a comment is thoughtful?

The rules of the game pull together the mechanics into a flow to motivate the player to achieve the mission.

6.2.3 Engagement Loop

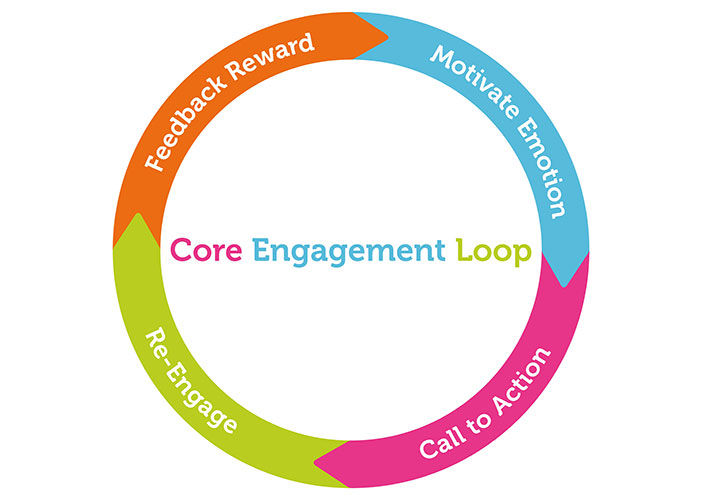

The core engagement loop refers to game mechanics combined with positive reinforcement and feedback loops that keep the player engaged in the game. This concept has been discussed by Amy Jo Kim (footnote 5), a renowned game designer.

The four main stages in the loop are:

Courtesy of Janaki Kumar and Mario Herger. Copyright: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported).

Courtesy of Janaki Kumar and Mario Herger. Copyright: CC-Att-ND (Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported). Figure 6.18: Core engagement loop

For example, a new player to a community site may:

This frequent invitation to interact with the system creates positive reinforcement and the player will be motivated to stay engaged with the gamified system.

6.3 Summary

Game mechanics are the most visible aspect of gamification. To be successful, mechanics need to be selected based on a thorough understanding of the player, the mission and human motivation.

In this chapter, we have presented a curated list of game mechanics that can help you start your journey into gamification. They are points, badges, leaderboards, relationships, challenges, constraints, journey, narrative, and emotion.

We guide you in creating a game plan that uses these mechanics as building blocks. The main elements to consider in the game plan are game economy, game rules, and the engagement loop.

The gamification system needs to engage the player continuously as part of a sustainable strategy.

6.4 Insights from SAP Community Network

In 2005, it was not common for communities to award points for participation. SCN ventured carefully into applying game mechanics by designing the system as follows:

This simple combination of points, badges and leaderboards created a positive dynamic. However, it also led to some unintended consequences, which we will discuss in the next chapter.

To be continued at the end of next chapter...