4 Tips to Amplify the Potential of Your UX/UI Design Portfolio

- 575 shares

- 1 mth ago

User experience (UX) design proposals are documents that outline a potential design project for prospective clients. They serve as a comprehensive plan and typically include a project’s approach, process, deliverables, timeline and commercial terms. They are platforms for designers to demonstrate their expertise, vision and proposed solutions to clients’ problems.

Much like any other design deliverable, the design proposal also begins with a careful understanding of the user—in this case, the potential client. Designers must understand what the client expects from a proposal and create one that matches their expectations.

Author, speaker and executive leadership coach Todd Zaki Warfel explains how to approach clients with design work.

Design proposals are the lifeblood of any UX design project. These proposals help provide a roadmap for the entire design process. They act as a reference for everyone involved and set clear expectations for the design solution.

A well-constructed UX design proposal can help designers:

Gain clarity and understanding about the project’s purpose and what they need to achieve.

Establish legal and contractual clarity, protecting the interests of both parties involved via clear terms and conditions, deliverables, timelines and budgets.

Accurately estimate costs, letting clients understand the financial aspect of the project.

Showcase creative vision and approaches to brand-relevant fineries. These include an appreciation for real-world user behaviors and compelling visual elements.

Streamline project management via well-defined project timelines and milestones.

Establish credibility and start to build solid and lasting trust with their client.

Designers create design proposals both when they are seeking new clients prospectively and when they are working on existing project discussions. In both scenarios, the key is for the designer to communicate clearly, present a compelling case for their design vision, and show an understanding of the client's needs and goals. A well-crafted design proposal can go a long way to winning business and ensuring project success for both clients and designers.

Since understanding the client means understanding users of the client’s brand too, designers should declare the full range of their skill sets in their proposals—and much more. A vital ingredient is to show how they’ll go about understanding users in a new contract. This includes leveraging UX research methods and approaches, such as quantitative research and qualitative research. For example, for prospective contracts, a designer might show how they made the best of card sorting, focus groups, user interviews and user journeys for previous clients in their UX portfolio. A vital point, of course, is to safely do so—that is, without violating non-disclosure agreements (NDAs).

The key point is for a designer to be ready to prove that they can well exceed a client’s expectations with solid experience and a keen, fresh eye for innovative solutions in the marketplace. This is essential in a fickle market, where mobile device users are used to discarding apps after just one use and many clients can’t afford to place their trust unless a convincing, compelling proposal helps them start to believe in the solution provider they have been hoping for. Designers have only seconds—and just one chance—to make a first impression and leap out from a thick pile of proposals. Consequently, they need to ensure they come across as the best UX brand to handle the problem at hand.

Here, Principal and owner of Lebsontech LLC, Cory Lebson explains what goes into branding as a UX professional:

*Be a UX thought leader* – how? You say, 'Well, I'm just new to UX; what do I have to say? No one wants to hear me.' It's not true. Put your *spin* on it. Put your *UX story* on it. You also need to *brand yourself as a UX professional*, so not just your resume, not just your portfolio, but you also need to *create your brand* in such a way that when people hear your story and look you up you, they say, 'Hey, you know what? Yeah. This is a UX professional.'

because people will look for you; they'll Google you on the Web; they will certainly look up your profile, your social media and so on. So, how do you as an individual come across in a Googleable way, in a visible way as a UXer? And how do you make sure that your UX brand stands up to scrutiny? Again, I said you have to be *honest* in your brand;

you cannot lie; you cannot make things up. You've got to be *honest*. But you can still provide a *frame*, you can provide the *narrative* about why you are a UX professional, why not only are you transitioning, but why it's been that way for a while. And it's all about the *frame* – the honest, true frame that you can say, 'Yes, I've been doing this stuff. I've been close enough that I understand.'

Proposals are essential for all kinds of designers. They could be product designers like app or web designers, service designers or other professionals in UX or user interface (UI) design. Proposals can vary in form, with different nomenclature for the introductory part (termed “executive summary”). However, these key parts provide essential information about the project's scope, objectives, requirements and more:

The title page includes the project's title, the designer's name or company name, the date of submission and possibly a logo or visual representation of the design proposal.

The introduction provides an overview of the design project, introduces the client's needs and sets the stage for the proposal. This can act as a cover letter.

This is to facilitate fast finding. The proposal is a design and should offer maximum convenience.

This section outlines the client’s specific requirements, goals and objectives. It contains a problem statement and helps show an understanding of the client's needs and how the proposed design will fulfill them.

The scope of work defines the specific tasks, deliverables and services that the designer will provide. It outlines what the design project will include and—particularly importantly—any limitations or exclusions.

This section details the designer's approach to addressing the client's needs and objectives. It may include design concepts, sketches or other visual representations to illustrate the proposed design solution.

The timeline section outlines the proposed schedule for the design project. It includes key milestones and deadlines.

Within the timeline, this is the expected delivery of design elements. Designers name UX deliverables associated with the project and where they feature (e.g., user research insights followed by proposed user flows and usability testing of low-fidelity prototypes). Both deliverables and timeline need to reflect how the design process will work for the project.

Watch Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) expert Professor Alan Dix explain the steps involved in a design process.

In this short video, we're going to look at the *process of interaction design*. Now we're going to talk about the steps you go through in order to create a new interaction, a new intervention. If you talk to interaction designers, they'll all have different ways of doing things. However, the general steps are not identical for each person, and they're not identical for each kind of process. But the general flow is fairly similar,

and we'll talk through a particular example. But you'll see slight differences if you look at it in different textbooks or talk to different professionals. There's basically a flow here from on the left-hand side, looking at the current situation and what the user needs, to on the right-hand side, actually creating some sort of artifact or system or piece of software or website that is actually fulfilling that need. So, that's the general flow. It's from need to fulfillment. There are complications – sometimes it works slightly the other way around.

But we'll take this, the most common flow through. What is it that's wanted? If you don't know what somebody wants, how can you produce something for it? And it seems obvious that that should be the case. But it's easy to *assume* you know what people want without even thinking about it. But there are different kinds of things. Sometimes, you go and watch people, observe what they're doing. You might interview them – talk to them,

look at some of the materials and some of the software or some of the systems they're already using. There are particular techniques – so, interview techniques; ethnography, which comes from anthropology. One particular problem that we often get when looking at the way people do things now is a tension between the current systems and the understanding we currently have and what is possible in the future. And it's quite often difficult for somebody to envisage that future.

So, having decided what's wanted, then there is usually some form of analysis stage, of making sense of that and sorting it, ordering it, giving it some sort of structure. Sometimes, that's more narrative things and sort of stories of how somebody uses a system. Sometimes, it's more structured. So, task analysis is more breaking down of what somebody does into separate steps and sub-steps.

So, there are different ways of doing this analysis, of "making sense" stage. Then you get on to actual design: What is it that we're going to produce? And that seems the most exciting and fun bit! Again, there are different techniques that you can use to help that. There are different guidelines you can use that say what kinds of things work for what kinds of problems. So, if you go to look at a lot of websites,

there are guidelines for how to design those, what are the appropriate techniques to use – some sort of more fundamental principles of design. Things like – for example, a principle might be giving somebody feedback once they've done an action. So, if somebody doesn't have feedback, they'll perhaps think something's gone wrong, it hasn't worked and try to do something else, when perhaps it's happened all along. And also a lot of techniques for managing the dialogue or navigation between pages,

between screens, the ways in which people interact. So, a variety of things happen in that design process. And that's sort of the micro-design – actually producing it. But having got an idea for what it is you want, then the normal next step is not just to deliver that to the user, but to create some sort of prototype system. Sometimes, that's no more than a sketch on a piece of paper that you show to someone. Sometimes, it might be a physical mock-up.

Product designers use blue foam. Or you might use a 3D printer or just cardboard to show somebody what something is going to be like. You might use Flash or some webpages to step through the major views, or even create software that is using programming, using quite detailed work, but it's still not necessarily the final system, but something to give somebody an idea of what it's going to be like. Now, the reason for this prototyping stage is that

*you never get it right first time*. Because people are people – you don't fully understand situations; you don't fully understand people. If you could really early on, then perhaps you wouldn't need it. If you have a perfect understanding of who people are, what they want, then you could just go and create it. But we never do. So, we always need to go through these stages of looking at something, finding out whether it works. To do that, we need what's called *evaluation*. You need to look at it.

And that might involve giving it to a user and saying, "Try it out." Sometimes, you give it to an expert – somebody who has a lot of understanding of the users – and use some heuristics and some methods and rules to look at it and ask questions. OK, that normally leads back into the analysis stage. You reanalyze the results of that evaluation. You use that to modify the design. You prototype again. You go round and round that loop. Sometimes, though, it gives you a more fundamental understanding.

So, the prototypes can just feed back in design. But sometimes they feed right back into reasking that question about what is wanted. So, this is particularly the case when it's a novel technology. So, you've got a new situation. It's not easy to know exactly what might be needed. I've got an example of this that goes back many years; so, you have to sort of adjust people's ideas.

And this was my first job as a practicing computer person. And it involves printouts – not web, not systems on a computer, but printouts from a computer. I was working in a County council – local government. And the Pensions Department wanted to add a few extra columns to the printout that they had each year that was used when they got to the end of the year.

Now this was on old, green-and-white-striped, 132-column paper. The head of the Pensions Department came to my office, and we talked about this for approximately one hour. And we were after three additional numbers; it wasn't that complicated. We decided at the end exactly what we wanted. And he was satisfied that I understood what he wanted. However, several times during that conversation I'd asked the question, "What is it that you use these numbers for?" Now, he must have answered, but I never felt satisfied to myself that I understood.

So, I knew what was wanted in terms of the printout, but not what it was for – not how it fitted into the bigger picture. Some time later, I modified programs. I produced a fresh list. I had an example list out – this is the prototype. And I rang him up and I said, "I've got the list out." And he said, "Oh, shall I come to your office?" And I don't know why – I didn't know the right things at this stage; I was very, very naive, very new to it all.

But I, perhaps by accident, did the right thing and I said, "Shall I come to *your* office?" So, I went to his office, which was himself plus a group of sort of clerical assistants who did work around. And I asked, and he looked at the printout and he looked at the numbers, and he said, "That's great!" And he was happy. He would have gone away happy at that point. But I asked again the question "What do you use it for?"

And he said, "Ah!" There was a big case of little filing cards; it had drawer after drawer of little 5-inch-by-3-inch filing cards. And he said, "Oh, we've got one card for each person: for each pensioner in the local authority. And what we'll do is we'll take out the card, we'll look at the line on the listing." And, pointing at the listing, he said, "We'll add this number to this number, take away that and write it down."

And I said to him, "Would you like me to give you that number?" And he looked at me and said, "Can you do that?" He didn't understand listing technology. Nowadays, it's a different set of issues. But even then, I think there was a – one of the problems, which is the common one, is the difference between what you see on the screen and what's inside the system. And it was a variant of that issue, so I think it's an issue that's still live. However, the crucial thing was *in his workplace*,

in the place where things were happening, he was able to articulate – and also, with the example in his possession. So, the prototype, in the context, enabled him to make sense of how it could change his work practice in a way that when we discussed it in the abstract, he couldn't do. So, that's line printers – a long way ago. But this is an example of what's now called a *technology probe*. This is when you create an artifact that allows people to see the potential.

So, for instance, on the island I live on – Tiree – I've been working with people on the island to produce a mobile application for the local historical archives. One of the first things we've done is created a small, handcrafted – not using back-end data, but handcrafted – not really what it will be like in any strong sense, but something to give an idea of what it will be like to have that mobile application

– so that, by having that, you can *begin* to have the conversations about what's possible. They change your view by – it's probing people, giving them the *tool* to see what's possible through giving them a technological artifact. OK and finally, having decided that you've got it good enough – not perfect, perhaps, but good enough – you then want to go on to implement and deploy it. Now, for that you *do* need a precise specification.

Early on, things can be a bit fuzzy. But in the end, as you deploy you need to know what you're going to deploy. Otherwise, what's going to happen is somebody who's going to be programming the system – it might be yourself; it might be somebody else – is creating that system, programming it or making the hardware around it: the physical hardware. And if you have not made the design decisions, they will make them without realizing they are. So, it's very important that they know precisely what they should be producing.

And there are additional things that often happen at that stage. There's the underlying software architectures that are crucial; documentation and help systems, although arguably you should be thinking about that during the design stage; maintenance – you know – are there going to be help desks? And recall it was the *intervention* that ultimately you design. So, in some sense, at the end of what's written here as the design process, and after you've implemented it, what you have is the artifact.

It's all these other things that go together to create the intervention in people's lives that changes it.

Here, the designer (or design team) highlights their relevant qualifications, experience and past projects that demonstrate their capability to successfully execute the proposed design project. When they include their UX portfolios, designers can showcase their skills in interaction design and other relevant areas.

This part includes the proposed cost of the design project, broken down into specific elements. It also outlines the payment terms, such as deposit requirements and invoicing details.

The terms and conditions section specifies the legal and operational aspects of the design project. This includes ownership of work, revisions, cancellation policy and any other relevant contractual details.

The conclusion summarizes the key points of the proposal and reiterates the benefits of the proposed design solution. Most importantly, it should encourage the client to take the next steps and present the designer’s contact information as clearly as a call to action.

Userlytics include 10 essential elements of a design proposal.

© Userlytics, Fair Use

Designers can use a recommended step-by-step guide to frame a persuasive proposal:

Before a designer starts drafting a proposal, they need to understand the client's brand thoroughly. They also must comprehend the needs, expectations, behavior, pain points, and more about the users the brand serves. For example, is it a niche startup, or a long-established client that has just had a brand makeover to appeal to a wider market? In an external context, it could be a B2B (brand-to-brand) or a B2C (brand-to-consumer) scenario. Or it could be a case where a company is working on an internal project for its employees, such as an intranet. In any case, this understanding ensures that their design proposal aligns with the existing brand identity, values and messaging. If a designer understands the brand well, they can tailor their design proposal to meet these objectives effectively and show great value in design decisions.

The problem statement is crucial. It should be specific, concise and directly related to the client’s needs and the client's business objectives. The most difficult part is to define the problem accurately and clearly—which many designers often overlook. A well-defined problem statement will guide the designer’s efforts properly. It will also help set the right expectations with the client and stakeholders.

The primary problem is that of the client. Then the designer can move on to examine the specific problems that the client’s users face, the causes of these and perhaps potential consequences of not resolving them. When they clearly articulate the problem, a UX designer demonstrates their understanding of the client's pain points. This sets the stage for proposing effective solutions. It also raises the chances of a successful pitch if the client sees their problem clearly articulated in the proposal. A Point of View (POV) is a meaningful and actionable problem statement that designers can leverage to access many such insights. They can use a Point of View Madlib to pinpoint their focus with the most clarity.

A Point of View Madlib helps designers clearly articulate a problem statement: “(The user) needs to (word or words reflecting the user’s need) because (the insight explaining the need).”

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

A designer now outlines the work they will do. This could include website design, user interface and experience design, or other forms of content creation. It’s important to set out the tasks, deliverables, services and anything else that relates to the limitations of the design work.

Designers must understand the full nature of the proposed work ahead of time—what they must do (e.g., usability testing) and what their services do not include. This helps prevent scope creep and surprises from miscommunication.

Once a designer has clearly stated the problem, it's time to tie in the solution and explain why it solves the client’s or customer's pain points. A well-articulated solution gives the client a clear, detailed plan for how the design work will address their specific problem. It also ensures they understand the proposed approach and what they can expect from the project.

Designers should outline the specific goals they aim to achieve through their proposed solution. These objectives should be measurable, realistic and directly linked to addressing identified problems. If the designer clearly defines the objectives, the client gains a clear understanding of what the project aims to achieve and how to measure success.

It’s crucial to allow for some fluidity. Design solutions typically evolve as more user insights arise and as the project progresses. Therefore, while the solution should be detailed and well-thought-out, it should also be flexible enough to accommodate changes and improvements. Meanwhile, the client should feel it starting to address their unique situation from the outset. They should sense the designer has empathy both for the users and themselves as the client.

Details are important here because they provide a clear roadmap of how designers plan to achieve the project goals. This includes the tools and techniques they will use, the stages of the design process, and how they will incorporate user feedback. This section should also explain how the design strategy aligns with the business objectives and user needs.

This video explains the need for empathy in design and how it guides decision-making:

Do you know this feeling? You have a plane to catch. You arrive at the airport. Well in advance. But you still get stressed. Why is that? Designed with empathy. Bad design versus good design. Let's look into an example of bad design. We can learn from one small screen.

Yes, it's easy to get an overview of one screen, but look close. The screen only shows one out of three schools. That means that the passengers have to wait for up to 4 minutes to find out where to check in. The airport has many small screenings, but they all show the same small bits of information. This is all because of a lack of empathy. Now, let's empathize with all users airport passengers,

their overall need to reach their destination. Their goal? Catch their plane in time. Do they have lots of time when they have a plane to catch? Can they get a quick overview of their flights? Do they feel calm and relaxed while waiting for the information which is relevant to them? And by the way, do they all speak Italian? You guessed it, No. Okay. This may sound hilarious to you, but some designers

actually designed it. Galileo Galilei, because it is the main airport in Tuscany, Italy. They designed an airport where it's difficult to achieve the goal to catch your planes. And it's a stressful experience, isn't it? By default. Stressful to board a plane? No. As a designer, you can empathize with your users needs and the context they're in.

Empathize to understand which goals they want to achieve. Help them achieve them in the best way by using the insights you've gained through empathy. That means that you can help your users airport passengers fulfill their need to travel to their desired destination, obtain their goal to catch their plane on time. They have a lot of steps to go through in order to catch that plane. Design the experience so each step is as quick and smooth as possible

so the passengers stay all become calm and relaxed. The well, the designers did their job in Dubai International Airport, despite being the world's busiest airport. The passenger experience here is miles better than in Galileo Galilei. One big screen gives the passengers instant access to the information they need. Passengers can continue to check in right away. This process is fast and creates a calm experience,

well-organized queues help passengers stay calm and once. Let's see how poorly they designed queues. It's. Dubai airport is efficient and stress free. But can you, as a designer, make it fun and relaxing as well? Yes.

In cheerful airport in Amsterdam, the designers turned parts of the airport into a relaxing living room with sofas and big piano chairs. The designers help passengers attain a calm and happy feeling by adding elements from nature. They give kids the opportunity to play. Adults can get some revitalizing massage. You can go outside to enjoy a bit of real nature.

You can help create green energy while you walk out the door. Charge your mobile, buy your own human power while getting some exercise. Use empathy in your design process to see the world through other people's eyes. To see what they see, feel what they feel and experience things as they do. This is not only about airport design. You can use these insights when you design

apps, websites, services, household machines, or whatever you're designing. Interaction Design Foundation.

The timeline section of the UX design proposal is essential for managing expectations and ensuring a smooth project flow. It outlines the projected timeline for each phase of the project, including key milestones and deliverable dates.

A designer’s timeline should consider the complexity of the project, the availability of resources, and potential dependencies. It’s crucial to be realistic and allow for flexibility in case of unforeseen circumstances. A well-planned and communicated timeline helps the client understand the project's progress and ensures that everyone is on the same page regarding deadlines and expectations. As delays can have a ripple effect on the entire project, it's essential to factor in some buffer time for unforeseen circumstances or changes in the project scope.

The deliverables section of the UX design proposal specifies the tangible outputs the designer will provide to the client throughout the project. It should include a comprehensive list of deliverables such as user research reports, wireframes, prototypes, usability test results and any other relevant documentation.

The designer should clearly outline the format, frequency and expected quality of these deliverables. For example, mockups may look like the finished project but can appear far sooner in the project. This section ensures that the client understands what they will receive at each stage of the project and helps manage their expectations.

A proposal should reflect a solid understanding that UX design involves important elements: to iterate to validate ideas and to iterate to design around constraints.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

In this section the designer showcases relevant work to account for the “why me?” dimension. They highlight projects that are like the one they’re proposing for the client. This will give a sense of the individual’s design style and capabilities.

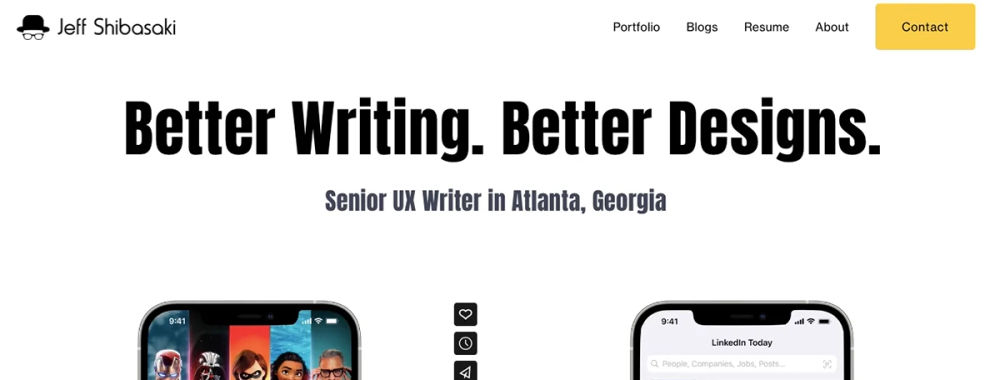

To highlight their experience, designers should showcase their past work, case studies and client testimonials that demonstrate their capabilities. Their UX portfolio should corroborate their claims and act as a design with its own superior UX as well. Designers should explain why they are the best choice for the project and how they can add value to the client's business. UX design is a burgeoning industry, and competition can be fierce. So, standing out from the crowd is crucial with a proposal that not only is professional and comprehensive but also uniquely fits the client's specific needs and goals.

Design lead for the AdWords Display & Apps Team at Google, Stephen Gay gives advice on how to craft a UX portfolio.

My number one advice would be when you're crafting your portfolio and you're crafting, you know, the way you present yourself. I was thinking about in buckets. You know what you've been working on. That's the project work that the wireframes, the deliverables, but also how you work, which is how you show up to your your office. How do you show up and work with your team, your existing design partners?

How do you show up and collaborate with other key cross-functional partners, your product managers, your engineering team? How do you like to interact? And that's the influencing skills, That's the collaboration skills. That's the negotiation skills and and skills that when you present your design work, it's how you move that design work forward. And I always look for both and a balance of both. If I see too much focus on the what,

I'll sense that tension or realize the person is more about championing the thing itself and not necessarily the outcome, which is, you know, we want to build great products for our customers, but we want to build it where our employees are happy and engaged. And I think that's that's how you create a great business and that's how you set the right tone.

A designer needs to show a client how much they will charge for the work, how they will calculate fees and what expenses or contingencies are included. It’s important to be transparent and fair about costs, and justify value and quality. It’s also vital to break estimated costs down into specific deliverables or phases. When it’s itemized this way and transparent, clients can understand what they are paying for, foster trust in the designer and make informed decisions.

It's better to overestimate (by a little) than underestimate. Include costs for research, design, testing and implementation, as well as any additional costs that may arise. A designer should be clear about pricing structure, whether it's hourly or project-based, and explain all costs. Designers include their fees, any additional expenses for resources or tools, and potential costs for changes or additions to the project scope. They should also describe acceptable payment options for the client.

It's crucial to specify clear terms and conditions for several reasons:

Clarity: They provide clear guidelines about the rules and requirements for both parties involved in a transaction or agreement.

Legal Protection: Terms and conditions can serve as a legal contract that may protect the rights of all parties.

Dispute Resolution: In case of disagreements, they are references to help resolve disputes.

Limitation of Liability: They can limit the liability of a service provider (the designer), clearly outlining what they are and aren’t responsible for.

Enforceability: Clearly stated terms and conditions are more likely to be enforceable in a court of law.

Disagreements can arise over any number of factors in a contract. A good terms and conditions section can account for contingencies.

© SHVETS production, Pexels License

The final step is to summarize the proposal and restate the value proposition. A designer needs to show the client why they should choose them for their UX project, what benefits and results that designer will deliver, and how they will exceed the client’s expectations.

It’s important to make a compelling last section here. A client needs to feel that urge to engage from a well-written conclusion that encapsulates why a particular designer is the way forward with the right solution and more.

It’s important to consider various factors that will influence both the creation and reception of a proposal. Key considerations are for designers to:

Research Thoroughly: Before drafting a proposal, a designer needs to deeply research the client’s business, industry and competitors—and, of course, the users who make up their market. It’s imperative to prove an understanding of the client's challenges and clearly articulate how the solution will address them.

Be Accessible and Approachable: Designers should show they are eager to start a dialogue and be open to discussions for gathering requirements and insights as they begin the design project.

Feasibility: Consider the practicality of the design in terms of budget, resources and time constraints.

Functionality: Ensure the design works well and serves its intended purpose.

Clearly and concisely articulate ideas and how they align with the client's goals. Avoid jargon and complex language. Ensure the client can easily understand the proposed solution, deliverables and costs. Remember that design is a conversation in itself; the proposal must reflect appreciation for a great user experience. Aim to answer potential questions within the proposal.

Deliver a professional format and tone throughout the proposal. Ensure perfect grammar and spelling, and a clean and clear layout.

Include detailed sketches, mockups or prototypes when possible.

Ensure a visually attractive design that aligns with the brand’s image. Use visuals such as images, diagrams and infographics to illustrate points and make the proposal more engaging. A strong proposal also needs to reflect a designer's grasp of great visual design. Balance the text with relevant visuals that effectively communicate ideas.

According to the Stanford University’s research, (published in the Stanford Credibility Project), nearly half of 2500+ participants assessed the credibility of websites based on their visual appeal. Remember the importance of visual appeal, both in design solutions and the proposal itself.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Discuss the budget openly with the client. This understanding guides the scope and scale of the project, and gives insights into the company culture behind the product or service.

Costing: Provide a clear breakdown of costs including design, production and any other associated fees.

Return on Investment (ROI): Explain how the design solution will benefit the client financially or in terms of brand value.

Assumptions: Identify and communicate any assumptions, like the availability of resources, access to user groups or the client’s active participation. This will help align expectations with the client and address potential risks or challenges upfront.

Scope of Work: Clearly define what is included to avoid scope creep.

Deliverables: List all deliverables, including file formats and any other specifics.

Portfolio: Include relevant examples of past work that demonstrate competence and style to answer the client’s “Why hire this designer?” in seconds.

Testimonials: Share testimonials from past clients to build trust.

Storytelling: Use a narrative to connect the client’s problem to the proposed solution.

Benefits: Focus on the benefits of the design, not just the features.

Show commitment to UX Research: Impress the client with an obvious commitment to conduct user research to understand the target audience's needs, behaviors, pain points, expectations, motivations, and more about their world.

Show commitment to User Testing: Plan for user testing as a necessity. This will validate the proposed solution and provide valuable feedback for refinement. When designers test with real users, they can reveal unforeseen issues and gain insights to significantly improve the design.

Effective UX design proposal tools and templates are widely available. Use them to help streamline the proposal creation process and enhance the quality and professionalism of proposals. They can also provide a platform for collaborative work. Good programs can save time, provide more insights, and help the client choose a designer or company faster. Designers should find ones that help them customize the look, feel and professionalism they want to cast to clients—for example, as freelance UX or UI designers.

PandaDoc is one of many solutions to generate a design proposal.

© PandaDoc, Fair Use

Follow-Up Plan: Have a plan for following up after sending the proposal.

Design is a collaborative process, and a proposal should reflect this. Be open to feedback from the client and be willing to revise the proposal based on their inputs. Designers who are feedback-oriented and -driven can show this commitment to evidence, flexibility and listening.

UX design agency Zengenti has used usability testing data in their design proposals to win projects. They find that including user testing data in their proposals provides a strong foundation for their design process and helps to reassure clients that their designs are evidence-backed.

© Simon Dumont, Fair Use

Some potential issues that can arise in a project relating to the proposal include:

Inadequate Market Analysis: This can result in a design that does not resonate with the target audience.

Misunderstanding the Brief: Not asking questions for clarity can cause a proposal to miss the mark.

Overpromising: Designers who make promises on deliverables or timelines that are unrealistic can damage trust. Also be clear about the job description. Many potential clients might have a vague idea of what’s involved in product design, and expect UI-UX designers to deliver in unrealistic timelines.

Vague Descriptions: Lack of specificity in the scope of work can lead to misunderstandings. For example, a proposal aimed at service design needs to consider every angle of the service design process.

Watch CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers explain the service design process.

Let's take a look at service design from a wide overview perspective. In the beginning of the process, you've got user research happening. And that's ethnography – right, to be clear: user research meaning "field studies" – ethnographic field studies. It's where personas come out of and journey maps come out of. And the reason you're doing that is you need to do that deep listening: What are the pain points? If the service design project is internally focused,

then that means service design interviews with stakeholders as well as subject-matter experts. You're going to also then have that *workshop* – that *stakeholder engagement piece* that we talked about. And so that stuff is happening up-front. From there, you're going to have the use of the template business model canvas, the value proposition canvas – those two canvases. And, to me, bringing the realistic inputs to those canvases, you can do it in a couple of hours: one hour, two hours even. If you have the right people in the room, you could even sit down.

You can do it across the whole process, too, by the way. You don't have to just do – the business model canvas is done up-front, yeah, in that first bit. But you can go back and do it again with another stakeholder. Like, for example, I've had so many projects where we're all the way to the testing phase and they bring in a new product manager or a new person to manage the whole – a program manager. And it's like those people *don't know*. So, going back and doing the business model canvas with them could be a good idea. From there, then you move into prototyping.

Now, when you do agile service design, you might do some quick prototyping up-front, – right off of those journey maps, right off of the user research. Traditionally, what you do is you take that journey map, though, and you move into the blueprint stage. So, you've got your business model, value proposition defined. Now, map it out in the service blueprint. That's where co-creation comes in – so, with stakeholders again. All the stakeholders are working on that blueprint together.

And you might also *map the ecosystem*. So, what's happening in the ecosystem that everyone needs to be aware of? And it's at that stage then you kick up into *service prototyping*. So, then you'll start building these actual prototypes. They might include UX design of apps or websites. That's fine. They might include physical, tangible theatrical acted-out, hands-on "fun stuff" – you know. And that's where we have the testing – think of it as user testing: *service user testing*.

And then, finally, once you've done that refinement, you're going to roll it out, roll out the service. And, of course, you're going to measure the service. You're going to do that initially with like a survey or you're going to use other tools from UX design or depending on what's appropriate. So, there may be web analytics, there may be exit surveys or you might do a *diary study*, which is a technique for user research you can use to assess the service. So, whatever the technique that's appropriate based on what you're building

– again, you know, depending on what you're building will determine the technique. But you want to get that feedback immediately, to find out. It may just be going into the environment and doing a service safari on your own service. So, that's an overview of the whole process, and key points there: user research up-front; stakeholder engagement throughout as well as some early iterations or loops of that if you're in an agile service design environment,

as well as remember the measurement.

Underquoting: Underestimating the costs can lead to financial loss or a decrease in quality to meet budgets.

Overquoting: Overestimating costs can make a proposal less competitive.

Designers do not typically include design ideas in a proposal, unless the client has agreed to sign an NDA, and offers compensation for drafting the proposal. These are usually called RFPs (request for proposal). Also, if the client and designer already know what's to be designed, then a solution overview will make sense. That is, it merely documents what the client has shared or what the client and the designer have mutually discussed before.

Copyright Infringement: Always ensure that the design does not infringe on any copyrights.

Ethical Design: Be mindful of ethical considerations in a design. Avoid anything that could appear offensive or inappropriate.

Remember, a great design proposal is not just about the aesthetics. It's also about how well it communicates the value of a design solution to the client. It should be clear, concise and compelling. It should also show extensive attention to detail in research, planning, foresight, empathy and vision. Overall, it travels ahead of the designer who relies on it. It’s often the first point of contact with a client, and so needs to portray the ultimate in professionalism, credibility, and much more.

“People hire who they know, who they like, and who they trust."

— Chris Do, CEO and Founder of The Futur

Take our How to Become a Freelance Designer course.

Watch our masterclass Win Clients, Pitches and Approval: Present Your Designs Effectively with Author, speaker and executive leadership coach Todd Zaki Warfel.

Read our piece How to Get Meaningful Design Feedback From Your Clients for more insights.

Read Jami Oetting’s article 15 Proposal Software Tools for Proposal Creation and Management for an array of proposal software to choose from.

See how prospective clients think in this insightful piece by Karthika G L: 7 Points To Consider When Choosing UI/UX Design Proposals For Your Business.

Find helpful points in this article from Simon Dumont: How to create a winning design proposal with user research.

Read Job M’s A UX Writer’s Guide To Writing A Content Design Proposal for additional insights.

The specific deliverables are different across different fields of design. Also, designers can continue to work on a product after launch and help to constantly improve or iterate on the design from testing and feedback. They can do this in an annual maintenance contract (AMC), for instance.

Also, UX designers are more service-oriented, despite the point that they may have tangible deliverables. Meanwhile, other types of designers tend to be oriented around one-time deliverables, handing off their designs before moving on.

Lastly, UX design proposals must leave scope for some flexibility, unlike other designers who have a more concrete scope of work. This is especially relevant for UX designers, as they will need to watch for scope creep in particular in some cases.

To ensure design proposals align with the client's budget constraints, designers should adopt a strategic approach:

Prioritize Needs over Wants: Differentiate between the essential features required for functionality and the additional features that are nice to have. Focus on delivering the core requirements within the budget.

Allocate Resources Wisely: Pick cost-effective solutions without compromising the quality of the design. This might include using open-source tools or modular design elements.

Design with Flexibility in Mind: Propose scalable solutions that allow for future expansion or enhancement when more funds become available.

Use Clear Communication: Maintain transparent communication throughout the project. Regularly update the client about the progress and any potential adjustments to stay within budget. Communicate effectively and be open and honest to build trust and simulate a face-to-face business environment virtually.

Use an Iterative Approach and Iterative Design Process: Good design iteration is about testing and refining ideas in stages, like prototype testing and incorporating user feedback. This prevents time-consuming and costly changes later in the project. On that subject, the proposal must clearly communicate this – address the iterative nature of the service, additional costs (if any) and the responsibilities of each party (say sign-offs or testing) for each iteration.

User research plays a critical role in a UX design proposal. It gives valuable insights into user needs, behaviors and preferences. It serves as the foundation for creating user-centered designs in the form of products and services that effectively meet the target audience's requirements.

Also, research helps inform the designer about the scope of work for the proposed solution.

Moreover, by knowing what the competition is, they can propose ideas on how to beat the competition for the design solution.

Watch this video for valuable insights into the timing and importance of user research in the design process.

In this presentation, we look at how user research fits into your design process and when to do different types of user studies. If you decide to invest time in doing user research, it's important that you time it so that you get as much out of your efforts as possible. Here, we look at when you should do different types of user research and how research fits into the different work processes.

Before you can decide when to do user research, you have to clarify *why* you're doing user research. You need different kinds of insights at different times in your design process. Let's have a look at the overall reasons for doing user research. You can do user research to ensure that you have a good understanding of your users; what their everyday life looks like; what motivates them, and so on. If you understand the people who use your product, you can make designs that are relevant for them. This type of research is typically *qualitative interviews and observations*.

You can also do tests of the user experience to ensure that your design has a high level of usability. Finally, you can evaluate on the impact of your design – for instance, on the number of customers or efficiency of work processes. As you can probably see, the different types of research fit into the design process in different ways. Let's start by looking at how each type of research fits into a simplified timeline for product development. Afterwards, we'll look into how user research fits into different types of development processes.

Research to ensure that your design is relevant to your users will typically be interviews and observations at the user's home or another relevant context. Since research to ensure that you create relevant products is meant to influence what type of product you will develop, most of this research takes place at the *start* of the development process, either *concurrently* with ideation work or *before* any concept work is done. You can also do research to validate your design direction, once you've developed some concept ideas

that you can show prospective users or during early product development. After release, you can do the same type of research to understand how customers are using your product, to explore if they need other features or offer opportunity scoping for your next project. And that, of course, leads you back to the beginning of your next product development process. Research to ensure that your designs are easy to use is mostly done as usability tests. It's important to start usability testing as early in the design or development process as possible

so that you have time to make changes to your design if the tests show that changing the design will benefit the product. If you use paper prototypes or similar materials, you can do early user testing before you have an interactive interface. User testing works well in an iterative process where you continually do user tests to ensure that your design is easy and pleasurable to use. Finally, research to measure the impact of your design mostly takes place *after* your product is released. The studies can then lead to new development and design changes.

If you're working on web-based products such as apps and web pages, it makes sense to keep evaluating on the user experience after your first release. One thing is a simplified timeline, but when you can do user research and how much research you can do really depends on what type of development process you work in. You can fit user research into most work processes depending on how ambitious you are. But it's easier in some work processes than in others. Let's take a look at what a work process that's optimized for user research looks like.

*User-centered design* is an overall term for work processes that place the needs and abilities of the user at the center of the development process. It's been described in different terms, but overall it's an iterative process where the first step is *user research* to ensure the relevance of the product. The second step is to *define* concepts based on user insights. The third step is *design and development*. And the fourth step is *user-testing the solution*. Ideally, this iterative process continues until evaluations show that the product is ready to be released.

After release, evaluations of the customer experience might lead to further development. By the way, design thinking is one of the most well-known user-centered work processes. As you can see, the steps involved in design thinking are almost identical to the overall steps of the user-centered design process. When you work in a user-centered process, user research is an integrated part of that process. But, in reality, many work processes are either not like that or deviate from the basic process in different ways.

So, how do you approach user research if you don't work in a clear-cut user-centered process? If research is not an integrated part of your work process and it's not up to you to change the way of working, you can still do user research, but it's up to you to decide when and how. So, let's look at some rules of thumb for deciding if, when and how to do user research. The sooner in your process you can do research, the bigger the impact of your research will be.

If you can do research before development starts, you can help ensure that you work on products that are relevant to your users. If you can do research early in development, you have more time to make changes to ensure great user experience before your product is released, and so on. Sometimes, you work in projects where you're not involved in all phases of the development. But you can still do smaller research projects that influence the part of the project you *are* working on. If you're a UX designer who's not involved in early concept development, it still makes a lot of sense to do *iterative user testing* of your designs.

If you don't have a process for how to handle research results, you should stick to research where you also have influence on any design changes that your research brings about. If you *are* involved in planning your development process, make sure that you schedule in some time to do user research. That way, you can be *proactive* with your research rather than reactive, so you don't have to scramble for resources when you suddenly need research to support your design decisions.

Sometimes, you don't have the resources to do all the user research you'd like to do. In that case, think about which type of research will have the *biggest impact* on your particular project and prioritize doing those studies. If you have influence over how you plan your development, iterative processes are almost always preferable when it comes to getting the most out of your user research. Iterative processes make you open to changing the end goal of your design based on the results of your user research.

In many projects, your time and resources to do user research are scarce. Luckily, you can do a lot with a little. You can, for instance, do user tests with paper prototypes rather than with fully interactive prototypes that require software programming. Just remember that the *validity* of your research is always the most important thing. So, if your time and resources for doing research are so limited that your results won't be sensible, it's better *not* to do any research. Best case = you'll waste your time and nothing comes from it.

Worst case = insights that don't really represent the user will impact important design decisions. Similarly, if you're working on a project that could benefit from user insights but you don't have the time or resources to make any design changes based on your research, you should save your research efforts for another time when they make more sense. So, what's the take-away? User research fits into the development process on all stages, depending on why you want to do user research. When you should do research, and what type of research you can do, depends on what your work process looks like.

If you work in a user-centered design process, user research is an integrated part of the process. If you *don't* work in a user-centered design process, it's up to you to make smart decisions about when and how to do research.

Visual design is especially important in a UX design proposal. It's not just about aesthetics in digital products like websites or apps. Visual design plays a crucial role in user experience as it influences usability, user interaction, user perception and the overall effectiveness of the design. The fundamental reason behind this fact is:

First Impressions: Visual design is often the first aspect of a product that users notice. For example, the first few seconds a user spends on a web design sets the tone for the user experience and can greatly impact user engagement. A designer’s UX portfolio should likewise impress clients.

Cultural factors greatly influence how designers create proposals. When designers understand and integrate these factors, they can create more inclusive, accessible, and effective designs for users from all cultural backgrounds.

User Behavior and Preferences: Different cultures have unique behavioral patterns and preferences. For example, color symbolism varies greatly across cultures. It affects how users perceive and interact with designs. Red in China, for instance, generally grabs users in different ways than it does users in the United States.

Language and Communication: Language is not just about translation but also involves understanding cultural nuances, idioms and context. Effective communication and communication styles in UX design consider these aspects to ensure clarity and relevance in visual design and beyond.

Navigation and Layout: Cultural differences in scanning patterns (like left-to-right or right-to-left reading) impact how users navigate and consume content. Designers must consider these variations to create intuitive and user-friendly layouts for different cultural groups.

Values and Norms: Cultural values, such as individualism versus collectivism, influence user expectations and interactions with technology across many groups of people. Designs for products or services that resonate with the target audience’s values will be more effective there.

Accessibility and Inclusion: Recognizing cultural diversity contributes to greater accessibility and inclusivity, long term. It ensures that products are usable and appealing to a broader audience and that they address at a high level the many pain points users face in problem solving.

Finally, with remote collaboration, it is extremely important to understand how people work in different cultures. What's acceptable in one region may be considered rude elsewhere. This will depend on what aspects of a proposal would have such cultural differences, though.

Do Detailed Requirement Analysis: Begin with a thorough analysis of the project requirements. Understanding the scope and complexity helps to make a more accurate estimation for all individual tasks combined.

Review Historical Data: Look at past successful projects with similar scopes. Historical data can provide insights into the time and resources needed for the project life cycle this time.

Break Down the Project: Divide the project into smaller, manageable parts from the early stages onwards. Estimate the cost for each project task and then sum up for the total project cost.

Include Contingency Plans: Always include a contingency budget for unforeseen circumstances or changes in project scope. This will ramp up the total cost but may make the difference between whether the project gets completed comfortably or not.

Consider All Factors: Include all aspects of the project in the cost estimate, such as design, development, testing, and any third-party service costs or time-consuming extras.

Regularly Communicate with Stakeholders: Engage with all stakeholders to ensure that they consider all needs during the project schedule and that the estimate is realistic for long-term project progress.

Use Project Management Tools: Leverage project management and estimation tools to help automate and standardize the estimation process.

Review and Adjust Regularly: Treat the estimate as a living document that’s adjustable as more information becomes available.

Designers can communicate complex design concepts to potential clients and clients effectively by using a few key strategies when they write a design proposal:

Simplify the Language: Use simple, jargon-free language. Avoid technical terms that may not be familiar to the client. This makes the proposal more accessible and easier to understand for a wide range of stakeholders.

Use Visual Aids: Include diagrams, sketches, wireframes, or prototypes for product or service design work. Visual representations can convey complex ideas more effectively than text alone. They help clients visualize the end-product of the design project and understand the design process.

Leverage Storytelling: Frame the design concept within a narrative. Explain how the design solves a problem or improves the user experience. Stories can make abstract concepts more tangible and relatable.

Use Modular Explanation: Break down the concept into smaller, manageable parts. Explain each part individually before showing how they integrate into the whole. This step-by-step approach prevents information overload.

Make Analogies and Metaphors: Analogies and metaphors can bridge the gap between unfamiliar design concepts or abstract ideas and the client’s existing knowledge. They make complex ideas more relatable and easier to grasp.

Involve Clients in the Process: Client involvement is a must. Ask for their input and address their concerns. This can increase their understanding and investment in the project.

Establish regular feedback loops: to ensure the client understands and is on board with the proposed design. This also allows for early detection and correction of any misunderstandings long before pain points turn up in user testing.

Watch this video by Morgane Peng, Design Director at Société Générale, for insights into how to work with feedback:

I've been talking to a lot of people in agencies, startups, even from the GAFAs, to Google, to Apple, et cetera. And I realized that we share the same frustrations – from people who don't get design. They may sound familiar. We'll see. The first one is, 'Can you make it *pretty*?'; 'Can you do the 'UX' (whatever it is)?'; and, 'Can you add this *wow* effect?'

And if you're like me – so, this is me – when you hear that, you would cringe. And I've heard them a lot. Because what we really want to hear is... 'Can you make it *usable*?'; 'Can *we* do the UX *together*?'; And the last one: 'Can you *tell me what's broken*?'

To effectively handle scope creep in UX design proposals, designers can employ several strategies:

Clearly Define the Project Scope: Start by establishing a clear, concise project scope. This includes outlining specific deliverables, timelines, and responsibilities. Designers who define the scope in a written document help ensure that all stakeholders have a common understanding of the project's boundaries, and what’s involved to complete the project and keep to the project schedule.

Establish a Change Request Process: Implement a formal process for handling changes or additions to the project. This process should include evaluating the impact of the change on resources, timelines, and costs. It should also require formal approval before any changes get made to any part of the project, regardless of whether they’re key elements or not.

Regularly Communicate with Stakeholders: Maintain open lines of communication with all project stakeholders. Regular updates and meetings help manage expectations and address any concerns early on and prevent surprises in project status reports.

Set Realistic Expectations: Designers should be realistic about what they can achieve within the given constraints of project timelines, project budget, and resources for project tasks. Overpromising can lead to scope creep as they try to meet unrealistic expectations for project team members and key stakeholders.

Monitor Project Progress and Consider Project Management Software: Keep a close eye on project progress. Regularly review the project status against the initial plan to identify any deviations early. Depending on the nature and type of project, consider using project management tools to aid in the management process.

Be Flexible, Yet Firm: While some flexibility is necessary, it's important to be firm about the project boundaries defined in the scope. Politely, but assertively, push back on requests that fall outside the agreed-upon scope. Clients may well agree not to assign tasks that go beyond agreed-upon terms, and therefore avoid scope creep and keep the project on track.

Designers can address client feedback or revisions in the design proposal process effectively by following these steps:

Actively Listen and Understand: When designers receive feedback, they should listen actively to understand the client's perspective and the reasons behind their suggestions or concerns. They should ask clarifying questions if necessary to fully comprehend the client as they collect feedback.

Maintain a Positive Attitude: Approach revisions and feedback positively. View them as opportunities for improvement rather than criticisms. That can foster a more productive and collaborative environment, and establish a long-term relationship. With the right mindset, designers can turn the opinions of unhappy customers into constructive feedback and develop good ideas.

Communicate Clearly and Regularly: Keep the lines of communication open. Regular updates on the status of revisions and clear explanations of any changes or challenges are crucial to maintain client trust and satisfaction.

Document Changes: Keep a record of all feedback and the corresponding changes made. This documentation can be useful for future reference and helps to ensure that no important details are overlooked. It also helps ensure more positive feedback when gathering feedback as the proposal manager can cross items off the list.

Set Boundaries and Expectations: Clearly define the scope of revisions and the proposal process. Set boundaries on the number and extent of revisions. It will prevent scope creep and ensure that the project remains on track according to the product roadmap.

Seek Consensus: Designers should work towards finding a solution that aligns with both the client's vision and their own design expertise. Strive for a consensus that satisfies both parties and upholds the quality and integrity of the design.

The following paper is a good resource for design proposal research:

Phillips, R., & Maier, A. (2020). How design proposals are evaluated: A pilot study. Proceedings of the Design Society, 1, 2109-2118.

This academic article, authored by Phillips and Maier in 2020, presents the findings of a pilot study on the evaluation process of design proposals. The study aims to understand how professionals in the field assess and decide on design proposals, focusing on the criteria and decision-making processes involved.

Here are some popular good books on design proposals:

1. Hass, C. (2015). Writing Successful UX Proposals. Morgan Kaufmann.

"Writing Successful UX Proposals" by Chris Hass is a pivotal resource for UX professionals and students who aim to master the art of creating effective and persuasive design proposals. This book provides a comprehensive guide on how to write proposals that clearly communicate the value and approach of UX projects. Hass covers critical elements such as understanding client needs, outlining project goals, and detailing methodologies. The book is particularly valuable for its insights into tailoring proposals to different audiences and its focus on winning strategies for securing project approval. This practical guide is essential for anyone looking to elevate their UX proposal writing skills.

2. Greever, T. (2020). Articulating Design Decisions: Communicate with Stakeholders, Keep Your Sanity, and Deliver the Best User Experience. O'Reilly Media.

"Articulating Design Decisions" by Tom Greever is an essential guide for UX designers and professionals involved in design processes. The book delves into the crucial skill of effectively communicating design decisions to stakeholders, colleagues, and clients. Greever addresses common challenges faced by designers, such as defending their decisions, managing feedback, and achieving consensus while ensuring the best user experience. He offers practical advice, strategies, and real-world examples to enhance communication skills in various scenarios. This book is especially valuable for its focus on the often-overlooked soft skills necessary for successful design projects.

Take our Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide course to get behind the client’s point of view for successful design solutions.

Watch our masterclass How to Build A Successful Portfolio with Chris Clark.

Read Write A UX Proposal: How-To Guide by Steven Douglas for further information.

See Offorte’s Proposal example: UX design for more insights.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Design Proposals by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Design Proposals with our course How to Create a UX Portfolio .

Did you know the average UX recruiter spends less than 5 minutes skimming through your UX portfolio? If you want to join the growing and well-paid field of UX design, not only do you need a UX portfolio—you’ll need a great UX portfolio that showcases relevant skills and knowledge. Your UX portfolio will help you get your first job interviews and freelance clients, and it will also force you to stay relevant in your UX career. In other words, no matter what point you’re at in your UX career, you’re going to need a UX portfolio that’s in tip-top condition.

So, how do you build an enticing UX portfolio, especially if you’ve got no prior experience in UX design? Well, that’s exactly what you’ll learn in this course! You’ll cover everything so you can start from zero and end up with an incredible UX portfolio. For example, you’ll walk through the various UX job roles, since you can’t begin to create your portfolio without first understanding which job role you want to apply for! You’ll also learn how to create your first case studies for your portfolio even if you have no prior UX design work experience. You’ll even learn how to navigate non-disclosure agreements and create visuals for your UX case studies.

By the end of this practical, how to oriented course, you’ll have the skills needed to create your personal online UX portfolio site and PDF UX portfolio. You’ll receive tips and insights from recruiters and global UX design leads from SAP, Oracle and Google to give you an edge over your fellow candidates. You’ll learn how to craft your UX case studies so they’re compelling and relevant, and you’ll also learn how to engage recruiters through the use of Freytag’s dramatic structure and 8 killer tips to write effectively. What’s more, you’ll get to download and keep more than 10 useful templates and samples that will guide you closely as you craft your UX portfolio. To sum it up, if you want to create a UX portfolio and land your first job in the industry, this is the course for you!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!