Flow Design Processes - Focusing on the Users' Needs

- 1k shares

- 4 years ago

User needs refer to users’ desires, goals, preferences and expectations when they interact with a product or service. These can encompass a wide range of factors such as functionality, usability, aesthetics, accessibility and emotional satisfaction. Designers research and understand needs to create user-centric designs that prioritize usability, satisfaction and more.

User Experience Strategist and Educator William Hudson explains where user needs fit into the design space.

Product design is the process of creating new products that people can use. It's about solving problems and making life easier or more enjoyable through goods or services. Think of anything you use in your daily life: a phone, a chair, a video game. All these items were once just an idea that a product designer brought to life. In User Experience, Product design is about creating digital things that are easy to use, work well and look good by combining user needs with business goals.

It involves making the whole journey for users from understanding what they need to making prototypes, testing, improving, and finally launching the product. It's all about figuring out what users want and finding smart ways to give it to them.

To design with user needs in mind comes with its own set of challenges. User experience (UX) designers face obstacles as they try to identify, prioritize and address user needs effectively from these users’ problems—and more. Some of the key challenges to their design work include:

Users come from diverse backgrounds and have different cultural, social and personal contexts. This real-life diversity introduces degrees of complexity for how designers might understand the people in their target audience’s needs. Designers have to think about these various factors—and carefully so. It’s vital for them to tailor solutions to accommodate those unique needs and preferences that different user groups actually have. Designers need to consider accessibility, too—as a legal requirement in many jurisdictions—to cater to the needs of users of all abilities.

Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains why designers need to consider users’ culture, for instance:

As you're designing, it's so easy just to design for the people that you know and for the culture that you know. However, cultures differ. Now, that's true of many aspects of the interface; no[t] least, though, the visual layout of an interface and the the visual elements. Some aspects are quite easy just to realize like language, others much, much more subtle.

You might have come across, there's two... well, actually there's three terms because some of these are almost the same thing, but two terms are particularly distinguished. One is localization and globalization. And you hear them used almost interchangeably and probably also with slight differences because different authors and people will use them slightly differently. So one thing is localization or internationalization. Although the latter probably only used in that sense. So localization is about taking an interface and making it appropriate

for a particular place. So you might change the interface style slightly. You certainly might change the language for it; whereas global – being globalized – is about saying, "Can I make something that works for everybody everywhere?" The latter sounds almost bound to fail and often does. But obviously, if you're trying to create something that's used across the whole global market, you have to try and do that. And typically you're doing a bit of each in each space.

You're both trying to design as many elements as possible so that they are globally relevant. They mean the same everywhere, or at least are understood everywhere. And some elements where you do localization, you will try and change them to make them more specific for the place. There's usually elements of both. But remembering that distinction, you need to think about both of those. The most obvious thing to think about here is just changing language. I mean, that's a fairly obvious thing and there's lots of tools to make that easy.

So if you have... whether it's menu names or labels, you might find this at the design stage or in the implementation technique, there's ways of creating effectively look-up tables that says this menu item instead of being just a name in the implementation, effectively has an idea or a way of representing it. And that can be looked up so that your menus change, your text changes and everything. Now that sounds like, "Yay, that's it!"

So what it is, is that it's not the end of the story, even for text. That's not the end of the story. Visit Finland sometime. If you've never visited Finland, it's a wonderful place to go. The signs are typically in Finnish and in Swedish. Both languages are used. I think almost equal amounts of people using both languages, their first language, and most will know both. But because of this, if you look at those lines, they're in two languages.

The Finnish line is usually about twice as large as the Swedish piece of text. Because Finnish uses a lot of double letters to represent quite subtle differences in sound. Vowels get lengthened by doubling them. Consonants get separated. So I'll probably pronounce this wrong. But R-I-T-T-A, is not "Rita" which would be R-I-T-A . But "Reet-ta". Actually, I overemphasized that, but "Reetta". There's a bit of a stop.

And I said I won't be doing it right. Talk to a Finnish person, they will help put you right on this. But because of this, the text is twice as long. But of course, suddenly the text isn't going to fit in. So it's going to overlap with icons. It's going to scroll when it shouldn't scroll. So even something like the size of the field becomes something that can change. And then, of course, there's things like left-to-right order. Finnish and Swedish both are left-to-right languages. But if you were going to have, switch something say to an Arabic script from a European script,

then you would end up with things going the other way round. So it's more than just changing the names. You have to think much more deeply than that. But again, it's more than the language. There are all sorts of cultural assumptions that we build into things. The majority of interfaces are built... actually the majority are built not even in just one part of the world, but in one country, you know the dominance... I'm not sure what percentage,

but a vast proportion will be built, not just in the USA, but in the West Coast of the USA. Certainly there is a European/US/American centeredness to the way in which things are designed. It's so easy to design things caught in those cultures without realizing that there are other ways of seeing the world. That changes the assumptions, the sort of values that are built into an interaction.

The meanings of symbols, so ticks and crosses, mostly will get understood and I do continue to use them. However, certainly in the UK, but even not universally across Europe. But in the UK, a tick is a positive symbol, means "this is good". A cross is a "blah, that's bad". However, there are lots of parts of the world where both mean the same. They're both a check. And in fact, weirdly, if I vote in the UK,

I put a cross, not against the candidate I don't want but against the candidate I do want. So even in the UK a cross can mean the same as a tick. You know – and colors, I said I do redundantly code often my crosses with red and my ticks with green because red in my culture is negative; I mean, it's not negative; I like red (inaudible) – but it has that sense of being a red mark is a bad mark.

There are many cultures where red is the positive color. And actually it is a positive color in other ways in Western culture. But particularly that idea of the red cross that you get on your schoolwork; this is not the same everywhere. So, you really have to have quite a subtle understanding of these things. Now, the thing is, you probably won't. And so, this is where if you are taking something into a different culture, you almost certainly will need somebody who quite richly understands that culture.

So you design things so that they are possible for somebody to come in and do those adjustments because you probably may well not be in the position to be able to do that yourself.

Copyright holder: Tommi Vainikainen _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Copyright holder: Maik Meid _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons _ Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Norge_93.jpg

Copyright holder: Paju _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons _ Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kaivokselan_kaivokset_kyltti.jpg

Copyright holder: Tiia Monto _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons _ Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Turku_-_harbour_sign.jpg

Sometimes, there can be a misalignment between what users actually need and what designers perceive as their needs. Designers may—unintentionally—impose their assumptions or biases onto the design, or they might rely on anecdotal evidence about users. That can end up taking the shape of a product or service that doesn’t fully meet the users’ needs—and fail in the marketplace. So, it’s crucial that designers do thorough user research and engage in continuous feedback loops. From that, they can make sure that the design runs in line with the actual user needs upon release of the product—and beyond. Another essential thing is to make sure that other team members, product managers and any other stakeholders who have an impact on the outcome are aware of the sheer need to get this alignment just right.

The need to match market research and field studies to mirror customer experiences accurately is an essential in all industries. In a similar vein, not doing enough user research is a common problem that can plague UX designers. And if they don’t have a deep understanding of user needs, designers might end up creating products that don’t effectively address user pain points, help in their problem-solving or even provide value. User research helps designers get insights into user behaviors, preferences, points of view and motivations. Quantitative and qualitative user research methods—including card sorting and semi-structured interviews, among many—enable designers to ask relevant research questions and make informed design decisions.

See why proper user research is so vital an ingredient in UX design:

When we hear the term 'user experience', we tend to think in terms of screens, websites, mobile apps or other smart technology. But that's just the tip of the iceberg. The Elements of User Experience In the book *The Elements of User Experience: User-Centered Design for the Web*, Jesse James Garrett outlines five elements of user experience: strategy, scope, structure, skeleton and surface.

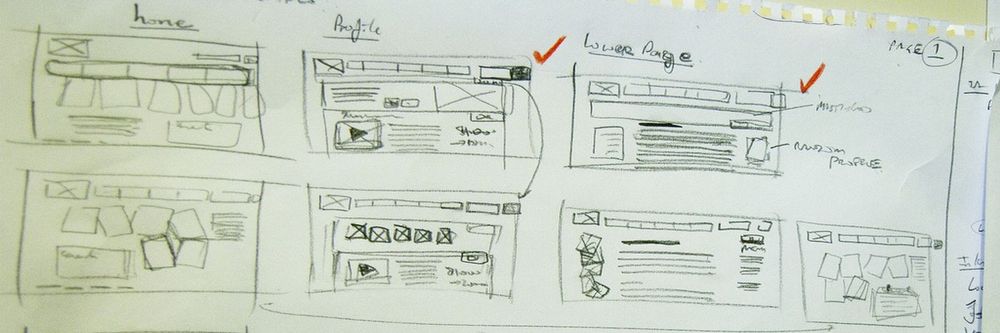

Before beginning any work, product teams conduct user research to understand who their target users are and what the users' needs are. It's important for teams to be aware of the business's goals and objectives because if the product does not return a profit, the business will not be sustainable. The strategy helps you identify *who you are designing for and why*. The scope defines *what you will be designing*. Designers work collaboratively with all stakeholders to identify

what features and functionality will help address user needs. While the *scope defines what a solution does*, the *structure defines how the product or solution works*. You create the blueprint of how the system works behind the scenes and how people, the users, interact with it. You then create the *skeleton*, laying out the first interfaces of the solution and creating the first tangible elements of user experience.

And, finally, you flesh out the skeleton to create the most visible element – the *surface* that your users see and interact with. Much like an iceberg, there is so much more to UX than meets the eye. And, just as in the case of an iceberg, each element of UX above and below the surface affects the other. Decisions taken at one plane can cascade up or down the layers. For example, if you introduce a new feature, a change in the scope, it will impact all the elements above.

You might even find users interacting with your product in unexpected ways, prompting you to rethink your strategy. There will likely be unknown considerations that emerge later, which might impact the experience. For example, if the team encounters technical challenges or budgetary constraints during development, they might have to revisit some design decisions. User experience design is concerned with *all* the decisions leading up to the surface,

from the most abstract to the most concrete, from the known to the unknown, and continues to evolve throughout the life of the product.

User needs evolve over time—and design solutions have to adapt accordingly. If designers fail to iterate and update designs based on changing user needs, that’s a mistake that can lead to outdated and irrelevant products. So, continuous evaluation and improvement are essential parts of making sure that the design does indeed stay aligned with users’ needs and expectations.

Another of the main challenges is the ambiguity over UX designers’ role and their responsibilities. Many people confuse UX design with graphic design, or they consider it a subset of user interface (UI) design. This muddiness blocks a clear view—and it can lead to misunderstandings and limitations in the scope of the UX designer's role. It’s a crucial thing for designers to educate stakeholders and be advocates for their—and the brand’s—users. That’s how they can establish a clear understanding of the value and impact of UX design as they stretch to address user needs properly.

It’s impossible to overstate the point that user research plays a critical role for designers to understand user needs and make sure that their design solutions effectively do address these requirements. Research splits between attitudinal and behavior approaches when designers and UX researchers are gathering information to guide their efforts and those of product developers and others in the design team.

The two approaches to user research.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

When designers conduct user research well, they gain valuable insights into their user’s world. These insights span user behaviors, motivations, pain points and preferences. This information guides the design process and enables designers to create user-centered solutions. More precisely, user research helps designers to:

User research helps validate—or challenge—assumptions about user needs. When designers directly engage with users, they can collect real-world insights that shape the design’s direction. They can avoid basing decisions on unfounded assumptions, too.

Sometimes, users mightn’t express their needs explicitly—or they might even be totally unaware of them. Through qualitative user research and quantitative user research methods—like interviews, surveys and observation—designers can uncover these hidden needs and work them into the design process.

User research provides designers with data-driven insights so they can prioritize features and functionality based on user needs and preferences. When designers have got these top of mind, it helps make sure that they and others in the design team can allocate limited resources to the most critical aspects of the design. For example, it takes a dedicated eye and specialized mindset to design for mobile users.

CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers explains the human-centered mobile design approach:

In this five-step process to designing for mobile, I want to point out some of the aspects or steps that are so critical and tell you why they're so critical and explain a little bit about how they work. The first step, *assess*, is requirements, your internal priorities,

your business objectives. And so – that's for step one – the last step, step five, should be familiar as well, it's *sketch*. So, we'll also add sketch, review, refine and have that sort of iteration. But it's what happens in steps two, three and four that are really, really critical and make the difference in a mobile UX design that outperforms and differentiates and creates a very, very deep bond with users and in a way that what we call *user adoption*.

So, step two, *understand* user needs, and that means understand their context of use, problems they're trying to solve, their tasks, their goals, all the things that make up personas, and then make up journey maps. Once you do that very crucial user research step, it's step three where you *define* your value proposition and your emotional value. So, emotional value is what users get from the app so that you essentially support their tasks,

you support their goals, you support a social aspect of their experience. You help them by giving them features and functionality that they find useful. Maybe you surprise them pleasantly, delight them. Understand their cultural needs. Understand their safety needs. Whatever it might be, you define that value proposition,

but also emotional value, that chance to connect with a user in such a way that they feel at home with your app or mobile content. So, that's step three. Step four is where you take what you've learned from user needs and from defining your value proposition and your emotional value, and you then *create a UX strategy* that's like a blueprint for when you get to sketching in the next step.

So, a differentiated UX strategy is something that makes your app special and connects with your users in a special way. You can't just generate this internally. A lot of product folks have pressure in their jobs, product managers, to differentiate, and they typically rely on market research, focus groups, surveys, that kind of thing. That's market research. And so, what we're talking about is if you get into the behavior of your users,

if you really dig into their contextual experience and what surrounds it and what they do as they go through their day and their lives and how they live it – if you get into that, then you can understand their needs, define their value proposition and their emotional value in a way that helps you differentiate. So, it might be how you approach the design, what features you drop

or that you add. In other words, the priorities and the good decision-making is what all of UX is about. It's about good design decision-making, And this five-step process is based on a very powerful and proven approach that I've taken in my work over the years, and this is basically the way to do it.

User research methods such as usability testing let designers observe how users interact with prototypes or existing designs. This feedback loop is something that helps them find potential usability issues—and helps them keep in line with requirements for accessible designs. It helps to both validate design decisions and make iterative improvements based on user needs, too.

Design Thinking is a process that revolves around a solid understanding of the needs of the users whom designers seek to help.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

In terms of design processes, user needs are the “sparks” with which designers seek to ignite their problem-solving “engine.” For example, in design thinking, designers empathize with users to be able to define their needs accurately. In any case, to uncover user needs effectively, research is key. UX designers get to work with various research methods and best practices—and here are some commonly used approaches:

Surveys and questionnaires are valuable tools for designers to collect quantitative data about users’ needs and preferences with. Designers can distribute surveys to a big number of users—and get insights from them on a broader scale. It’s important for them to carefully design the surveys they send out, too. And designers really need to make sure that the questions are clear, concise and, indeed, relevant to their research objectives.

Surveys require careful thought to tailor them correctly to the users who can supply vital information about their needs.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

In-depth interviews and focus groups help shed qualitative insights on user needs. Whenever designers get into direct conversations with users, they can delve deeper into the latter’s experiences, plus their motivations and pain points. These methods permit open-ended discussions that uncover rich, contextual information about users’ needs.

When designers and UX researchers watch users in their natural environments—or shadow them as they’re interacting with a product or service—it gives valuable insights into these users’ behaviors, frustrations and needs. This method lets designers and others in the design team get to really understand the context in which users operate and so find pain points or areas for improvement.

When designers leverage analytics tools and analyze user data, it can offer up valuable insights into user behaviors and needs. If designers look carefully at user interactions, patterns and engagement metrics, they can identify areas where users may encounter difficulties—or unmet needs.

Personas are fictional representations of target users that encapsulate their characteristics, needs and goals—they’re extremely valuable tools. They’re an essential part of the design thinking process, too. When designers create personas that are based soundly on user research, they can develop a deeper understanding of their target audience—and from there design solutions that truly meet their specific needs.

Author and Expert in Human-Computer Interaction, Alan Dix explains the importance of personas and how to get them right for design projects:

Personas are one of these things that gets used in very, very many ways during design. A persona is a rich description or description of a user. It's similar in some sense, to an example user, somebody that you're going to talk about. But it usually is not a particular person. And that's for sometimes reasons of confidentiality.

Sometimes it's you want to capture about something slightly more generic than the actual user you talked to, that in some ways represents the group, but is still particular enough that you can think about it. Typically, not one persona, you usually have several personas. We'll come back to that. You use this persona description, it's a description of the example user, in many ways during design. You can ask questions like "What would Betty think?"

You've got a persona called / about Betty, "what would Betty think" or "how would Betty feel about using this aspect of the system? Would Betty understand this? Would Betty be able to do this?" So we can ask questions by letting those personas seed our understanding, seed our imagination. Crucially, the details matter here. You want to make the persona real. So what we want to do is take this persona, an image of this example user, and to be able to ask those questions: will this user..., what will this user feel about

this feature? How will this user use this system in order to be able to answer those questions? It needs to seed your imagination well enough. It has to feel realistic enough to be able to do that. Just like when you read that book and you think, no, that person would never do that. You've understood them well enough that certain things they do feel out of character. You need to understand the character of your persona.

For different purposes actually, different levels of detail are useful. So I'm going to sort of start off with the least and go to the ones which I think are actually seeding that rich understanding. So at one level, you can just look at your demographics. You're going to design for warehouse managers, maybe. For a new system that goes into warehouses. So you look at the demographics, you might have looked at their age. It might be that on the whole that they're older. Because they're managers, the older end. So there's only a small number under 35. The majority

are over 35, about 50:50 between those who are in the sort of slightly more in the older group. So that's about 40 percent of them in the 35 to 50 age group, and about half of them are older than 50. So on the whole list, sort of towards the older end group. About two thirds are male, a third are female. Education wise, the vast majority have not got any sort of further education beyond school. About 57 percent we've got here are school.

We've got a certain number that have done basic college level education and a small percentage of warehouse managers have had a university education. That's some sense of things. These are invented, by the way, I should say, not real demographics. Did have children at home. The people, you might have got this from some big survey or from existing knowledge of the world, or by asking the employer that you're dealing with to give you the statistics. So perhaps about a third of them have got children at home, but two thirds of them haven't.

And what about disability? About three quarters of them have no disability whatsoever. About one quarter do. Actually, in society it's surprising. You might... if you think of disability in terms of major disability, perhaps having a missing limb or being completely blind or completely deaf. Then you start relatively small numbers. But if you include a wider range of disabilities, typically it gets bigger. And in fact can become

very, very large. If you include, for instance, using corrective vision with glasses, then actually these numbers will start to look quite small. Within this, in whatever definition they've used, they've got up to about 17 percent with the minor disability and about eight percent with a major disability. So far, so good. So now, can you design for a warehouse manager given this? Well,

you might start to fill in examples for yourself. So you might sort of almost like start to create the next stage. But it's hard. So let's look at a particular user profile. Again, this could be a real user, but let's imagine this as a typical user in a way. So here's Betty Wilcox. So she's here as a typical user. And in fact, actually, if you look at her, she's on the younger end. She's not necessarily the only one, you usually have several of these. And she's female as well. Notice only up to a third of our warehouse ones are female. So

she's not necessarily the center one. We'll come back to this in a moment, but she is an example user. One example user. This might have been based on somebody you've talked to, and then you're sort of abstracting in a way. So, Betty Wilcox. Thirty-seven, female, college education. She's got children at home, one's seven, one's 15. And she does have a minor disability, which is in her left hand. And it's there's slight problem in her left hand.

Can you design, can you ask, what would Betty think? You're probably doing a bit better at this now. You start to picture her a bit. And you've probably got almost like an image in your head as we talk about Betty. So it's getting better. So now let's go to a different one. You know, this is now Betty. Betty is 37 years old. She's been a warehouse manager for five years and worked for Simpkins Brothers Engineering for 12 years. She didn't go to university, but has studied in her evenings for a business diploma.

That was her college education. She has two children aged 15 and seven and does not like to work late. Presumably because we put it here, because of the children. But she did part of an introductory in-house computer course some years ago. But it was interrupted when she was promoted, and she can no longer afford to take the time. Her vision is perfect, but a left hand movement, remember from the description a moment ago, is slightly restricted because of an industrial accident three years ago.

She's enthusiastic about her work and is happy to delegate responsibility and to take suggestions from the staff. Actually, we're seeing somebody who is confident in her overall abilities, otherwise she wouldn't be somebody happy to take suggestions. If you're not competent, you don't. We sort of see that, we start to see a picture of her. However, she does feel threatened – simply, she is confident in general – but she does feel threatened by the introduction of yet another computer system. The third since she's been working at Simpkins Brothers. So now, when we think about that, do you have a better vision of Betty?

Do you feel you might be in a position to start talking about..."Yeah, if I design this sort of feature, is this something that's going to work with Betty? Or not"? By having a rich description, she becomes a person. Not just a set of demographics. But then you can start to think about the person, design for the person and use that rich human understanding you have in order to create a better design.

So it's an example of a user, as I said not necessarily a real one. You're going to use this as a surrogate and these details really, really matter. You want Betty to be real to you as a designer, real to your clients as you talk to them. Real to your fellow designers as you talk to them. To the developers around you, to different people. Crucially, though, I've already said this, there's not just one. You usually want several different personas because the users you deal with are all different.

You know, we're all different. And the user group – it's warehouse managers – it's quite a relatively narrow and constrained set of users, will all be different. Now, you can't have one persona for every user, but you can try and spread. You can look at the range of users. So now that demographics picture I gave, we actually said, what's their level of education? That's one way to look at that range. You can think of it as a broad range of users.

The obvious thing to do is to have the absolute average user. So you almost look for them: "What's the typical thing? Yes, okay." In my original demographics the majority have no college education, they were school educated only. We said that was your education one, two thirds of them male – I'd have gone for somebody else who was male. Go down the list, bang in the centre. Now it's useful to have that center one, but if that's the only person you deal with, you're not thinking about the range. But certainly you want people who in some sense

cover the range, that give you a sense of the different kinds of people. And hopefully also by having several, reminds you constantly that they are a range and have a different set of characteristics, that there are different people, not just a generic user.

User journey mapping visualizes the user's experience throughout their interaction with a product or service. This method helps designers identify pain points, opportunities and moments of delight along the user journey. When designers understand the user's needs at each touchpoint, they can optimize the experience and address any gaps or challenges for these users as well.

CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers explains how important journey mapping is—in this case as it applies to service design.

I wanted to just spend a little bit of time on the *user journey*. So, we can see how important user research is to creating really compelling value propositions and creating value for organizations that are trying to use service design to innovate, improve, streamline and smooth out. Well, there's nothing better to tackle that with than the user journey.

I wanted to just spend a little bit of time on this technique in case you didn't have that much experience with it or maybe you were doing journeys in a way that was different to the way I'm going to present to you. At least, I just wanted to share a template with you that can give you better access to what you're looking for. For me, now, a journey is something that you *build on*. So, first off it's your *customer journey*.

And on that is your service blueprint. And remember that the journey is going to reveal those cross-channel like, say, *breakpoints*, *pain points*, *disconnects* that you can map in the different *swim lane diagrams* – is the official term for a journey map. So, it comes from that – these swim lanes. And so, you'll have like maybe your channels here – you know – you'll have your user tasks here, pains and gains, or you can just have positive (+) or negative (-).

And I tend to change my user journeys, try and improve them, try and improve them. One of the problems that I find with journey maps – and they became very popular, I think around 2010, maybe, was the heyday of user journeys – 2010 / 2012, maybe. It was all about this beautiful big visualization. Let's be clear: A customer journey map is *not* about impressing your team

with really cool, big swim diagram visualizations with tons of little icons. It's a document like all deliverables in a human-centered design perspective. It should work for the internal teams that are using it as a decision-making document *as well*. The thing about the journey map that's particularly of value to the service designer is that it's happening across time

or across stages or across goals. So, the stages of, say, the life cycle – you know – you might have Research, Compare, Purchase, then the Return shopping. In other words, it's not just the purchase. A lot of conversion optimization and approaches to selling online just focus on this part here: the compare and purchase, or the funnel – if you will – the purchase funnel. And I think it's important to have the acquisition as much as the retention.

This is the conversion here. So, these two steps are the conversion steps. It's important to have *all* those steps represented. *Happy / sad moments* – you can have a little smiley face; *disconnects and breaks* – you know – so that you're like: "Ah! This is a break right here. They're on their phone, and they're researching, but the site's not responsive or it's *partially* responsive. And then, compare – when they go to compare, it only allows three items. So, it's like "Ohh!" – and then we have a quote from the user going:

"Why does this only allow (imitated mumbling)?!" – you know – something communicating the pain point. The other thing it's going to have is your reflections from your ethnography, from your personas. It's going to have those real-world contexts, basically. Instead of basically making it up and doing it internally, you're going to base it on user data. You'll also want to have *recommendations*. So, down here at the bottom you can have a list of recommendations

as well. This is an example of a journey map we created. And you can see the touch points we've added along the way. So, we have these different stages. We've got this – as the user walks through. So, we have Pre-apply, Apply, Post-apply. This is an online application journey. And we have the various channels that are occurring there. We've got the pain points represented. And the steps are:

Discover, Research, Apply, Manage and Dream. Discover was important because a lot of people didn't know that the offers were there. This is for getting an account. And basically the value proposition is you're going to have these offers – targeted offers – sent to you. So, the key is to find out how people are currently applying and at what stage makes sense to offer them these upsells, basically. And that's the value add that's being offered here.

Several tools and frameworks can assist UX designers to understand user needs and incorporate them into the design process. Here are some commonly used tools:

These maps help designers get a deeper understanding of users as they map the users’ thoughts, feelings, needs and behaviors. When designers visualize these aspects, they can empathize with users and design solutions that truly address their needs in an effective way.

Empathy maps can reveal critical insights to guide the design process.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

User personas deserve a second mention in particular here. They bring home a human-centered perspective—one that informs design decisions and makes sure that the design actually lines up with the target audience's goals and preferences.

User personas contain a wealth of information and insights—nuggets that designers can tap to more effectively meet these users’ needs.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

User stories are concise narratives that describe a specific user's needs, their goals—and their expected outcomes. They help designers keep a user-centered focus throughout the design process and make sure that the end product really does address user needs effectively.

UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains user stories and their significance:

User stories are the actual tasks that are written on the cards or sticky notes in your Kanban board. In Agile methodologies, these are often small enough that they can be done in a matter of hours or sometimes a day or two. Many teams write them from the perspective of the user. So, you may end up seeing things in the form of: 'As a _____ I would like to _____ so that I can _____.' To fill in those blanks just a little bit,

'As a *user type* I would like *some goal or action*, so that *outcome*.' And an actually useful example would be something like: 'As a *job applicant* I would like to save my *resume information*, so *I don't have to re-enter it every time I apply for a new job*. The idea here is that the engineer who is implementing this user story knows not just what the *description of the feature* is but *what the outcome is and why the user would want that outcome*. Sometimes the user stories are accompanied by various types of design deliverables.

Also, some teams don't phrase the user stories in exactly this way. You're going to have to adopt the patterns of your team or work with them to come up with something that works better for you.

User testing is all about observing users as they interact with a prototype or an existing design. When designers gather feedback and insights directly from users, they can find usability issues, validate design decisions and align their product with users’ needs—and that includes fine-tuned aspects of visual design.

Numerous case studies illustrate how companies have successfully identified and addressed user needs in their products and services. Notable examples include these:

Apple revolutionized the smartphone industry—by understanding and addressing user needs very effectively. They identified the need for a device that combines multiple functionalities—such as phone calls, internet browsing and music playback—and do it in a user-friendly and intuitive way. When Apple designed the iPhone with a sleek interface, touch screen technology and an ecosystem of apps, they met the diverse needs of users—and created a truly groundbreaking product.

Apple recognized the need to meet their users’ needs—in this intuitive handheld package, available as popularly desired.

© Apple, Fair Use

Slack identified the need for a streamlined and collaborative communication tool for teams to use. And when Slack designed a platform that integrates messaging, file sharing and project management features, they addressed the pain points associated with fragmented communication channels and improved team collaboration. Their user-centric approach has made Slack a very widely adopted tool for businesses all over the world.

Uber identified the need for a really convenient and reliable transportation service. They focused on user needs—such as ease of use, quick access to drivers and transparent pricing. From there, they revolutionized the transportation industry.

Airbnb recognized the users’ need for affordable and unique accommodations while they’re traveling. And when Airbnb created a platform that connects travelers with hosts offering unique and personalized lodging options, it was a game-changer—and they disrupted the traditional hotel industry. They addressed user needs for authenticity, affordability and immersive travel experiences—efforts that resulted in a highly successful platform.

Airbnb’s solid grasp of their users’ needs has translated to a highly intuitive site and app that bridges the divide between problem and solution effectively, seamlessly and desirably.

© Airbnb, Fair Use

To uncover and design for user needs effectively, UX designers can follow these practical tips:

Invest time and resources to conduct thorough user research and so get a deep understanding of user needs, motivations and pain points. Use a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods to gather rich insights.

One of the best “keys” to shed light on the problem space is a problem statement. Otherwise called a Point of View (POV), it is a concise description of the design problem, and encapsulates the user’s needs.

Designers identify how to address the user’s needs when they set out what it is that users require in a scenario. Like so:

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

In the above example, the designer has set out the user as a type of person with a sharply defined need. This translates to the insight from which the designer can start to work on a potential solution.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Include users in the design process through user testing, co-creation sessions and feedback loops. When designers engage their users, they can make sure that they consider these needs at every stage—and so lessen the risk that anything gets misaligned. Designers should plant themselves firmly in their users’ shoes and work to understand their goals, motivations and—of course—challenges. This empathy will guide the design decisions and help create user-centered solutions.

See why empathy for users is the most fundamental ingredient in a design process.

Do you know this feeling? You have a plane to catch. You arrive at the airport. Well in advance. But you still get stressed. Why is that? Designed with empathy. Bad design versus good design. Let's look into an example of bad design. We can learn from one small screen.

Yes, it's easy to get an overview of one screen, but look close. The screen only shows one out of three schools. That means that the passengers have to wait for up to 4 minutes to find out where to check in. The airport has many small screenings, but they all show the same small bits of information. This is all because of a lack of empathy. Now, let's empathize with all users airport passengers,

their overall need to reach their destination. Their goal? Catch their plane in time. Do they have lots of time when they have a plane to catch? Can they get a quick overview of their flights? Do they feel calm and relaxed while waiting for the information which is relevant to them? And by the way, do they all speak Italian? You guessed it, No. Okay. This may sound hilarious to you, but some designers

actually designed it. Galileo Galilei, because it is the main airport in Tuscany, Italy. They designed an airport where it's difficult to achieve the goal to catch your planes. And it's a stressful experience, isn't it? By default. Stressful to board a plane? No. As a designer, you can empathize with your users needs and the context they're in.

Empathize to understand which goals they want to achieve. Help them achieve them in the best way by using the insights you've gained through empathy. That means that you can help your users airport passengers fulfill their need to travel to their desired destination, obtain their goal to catch their plane on time. They have a lot of steps to go through in order to catch that plane. Design the experience so each step is as quick and smooth as possible

so the passengers stay all become calm and relaxed. The well, the designers did their job in Dubai International Airport, despite being the world's busiest airport. The passenger experience here is miles better than in Galileo Galilei. One big screen gives the passengers instant access to the information they need. Passengers can continue to check in right away. This process is fast and creates a calm experience,

well-organized queues help passengers stay calm and once. Let's see how poorly they designed queues. It's. Dubai airport is efficient and stress free. But can you, as a designer, make it fun and relaxing as well? Yes.

In cheerful airport in Amsterdam, the designers turned parts of the airport into a relaxing living room with sofas and big piano chairs. The designers help passengers attain a calm and happy feeling by adding elements from nature. They give kids the opportunity to play. Adults can get some revitalizing massage. You can go outside to enjoy a bit of real nature.

You can help create green energy while you walk out the door. Charge your mobile, buy your own human power while getting some exercise. Use empathy in your design process to see the world through other people's eyes. To see what they see, feel what they feel and experience things as they do. This is not only about airport design. You can use these insights when you design

apps, websites, services, household machines, or whatever you're designing. Interaction Design Foundation.

Place user needs at the center of the design process—throughout all the efforts. It’s a vital thing to do, to continuously refer back to user research and personas—to inform design decisions, plus make sure that the design is on line with users’ expectations.

Embrace an iterative design process—and be sure that it’s one that permits continuous improvement with user feedback as a basis. It’s a vital thing to test and refine the design regularly—to make sure that it stays aligned with user needs as they evolve.

Get working with stakeholders from different disciplines—like development, marketing and customer support. When designers involve diverse perspectives, they can get a more holistic understanding of user needs and work to make truly comprehensive solutions. That’s where an Agile process can come in especially handy, for instance.

UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains how valuable cross-functional teams are in design:

Cross-functional teams, unlike silos, have all the people necessary to build a specific thing together. Let's look at an example. Imagine you're on a team that is supposed to build the onboarding flow for a new app that helps connect job applicants with jobs. You can't build the whole thing with just designers. Or with just engineers, for that matter. I mean, you probably could do it with just engineers, but it's a terrible idea.

A cross-functional team for this onboarding work might include a few engineers, perhaps some for the front end and some for the back end. Might include a designer, a researcher, a product owner or manager, maybe a content writer or a marketing person. In an ideal world, all of these folks would only work on this particular team. In the real world, where we actually live, sometimes folks are on a couple of different teams and some specialists may be brought in to consult. For example, if the team needed help from the legal department to explain some of the ramifications of a specific decision,

a cross-functional team would have a dedicated legal expert they could go to. But that legal expert might also work with lots of other teams. In agile environments, the cross-functional team generally sits together or if remote, has some sort of shared workspace. They all go to the required team meetings. They understand the goal of the team and the users. They're experts, or they soon become experts, on that onboarding flow. Contrast this to how it might be done in a siloed environment. In that case, you might have different people assigned to the team depending on need, which can seem really flexible.

Until you realize that you end up with five different designers working on the project all at different times and they all have to be brought up to speed and they don't really understand why the other designers made the decisions that they did. Same with the engineers. And do not get me started on legal. Silo teams tend to rely more on documentation that gets handed between groups. And this can lead to a waterfall project where project managers or product managers work on something for a while to create requirements, which they then hand off to designers who work on designs for a while

and then they pass the deliverables on to engineering, who immediately insists that none of this will work and demands to know why they weren't brought in earlier for consultation. You get it. By working in cross-functional teams instead, the people embedded on the project get comfortable with each other. They know how the team works and can make improvements to it. They come to deeply understand their particular users and their metrics. They actually bring engineering and even design and research into the decision making process early to avoid the scenario I described above.

Stay informed and up-to-date about current UX trends and emerging technologies. If designers keep up with developments in the industry, they can be well positioned to stay ahead—and anticipate future user needs and design solutions that are truly ahead of the curve.

Overall, designers need to really understand and address user needs; it’s something that perhaps should go without saying. Still, only when designers do this—and only when they do it well, too—can they hope to create successful and impactful user experiences. It’s utterly vital to approach matters in a proper way—and that includes the need to prioritize user-centered design and continuously iterate on the design based on user feedback. That’s how designers can create products and services that provide value, delight users and drive business success.

Remember, user needs are at the very core of UX design. So, it’s vital to design with empathy and a deep understanding of users of all types. It’s also extremely important to factor in accessibility considerations mindfully—and not as an afterthought. These considerations are absolutely key to getting in step with user needs, user flows—and then creating experiences that are meaningful and impactful for all users.

Take our User Research – Methods and Best Practices course.

Find further insights and tips in our piece Flow Design Processes – Focusing on the Users’ Needs.

Read User Need Statements: The ‘Define’ Stage in Design Thinking by Sarah Gibbons for more in-depth details.

Check out this piece, Best 18 Examples of User Needs by UIHUT, for fascinating examples, insights and more.

Read Top Methods of Identifying User Needs by UXPin for more information.

In digital products, user needs often revolve around efficiency, ease of use, personalization, accessibility and security. Here are some common examples:

Efficiency and productivity: Users want to get tasks done quickly and easily. For instance, in a project management app, being able to create and delegate tasks with a few clicks meets this need.

Ease of use: Simplicity is key, and a user-friendly interface—with intuitive navigation and clear instructions—lets users use a product and not get confused along the way. For an example, think of a banking app that simplifies the process of transferring money.

Personalization: Users appreciate it whenever digital products cater to their preferences and history. Streaming services like Netflix recommend shows and movies based on past viewing habits—and so provide a personalized experience.

Accessibility: Digital products must be usable for everyone—and that includes those with disabilities. Features like text-to-speech for visually impaired users or voice recognition for those who can’t use traditional input devices are extremely important.

Security and privacy: In an era where data breaches are common things, users need to feel extra secure that their information really is safe. Secure login methods and transparent privacy policies are examples of how digital products can meet this need well.

Entertainment and engagement: Games, social media platforms and video streaming services have got to provide content that’s engaging so that users keep coming back.

Learning and development: Educational apps need to offer valuable content and in an engaging way—helping users learn new skills or knowledge efficiently.

Social connection: Especially in social media apps, users want to connect with others easily, share content, and communicate in real-time.

Watch our topic video on accessibility to appreciate the need to design with accessibility in mind.

Accessibility ensures that digital products, websites, applications, services and other interactive interfaces are designed and developed to be easy to use and understand by people with disabilities. 1.85 billion folks around the world who live with a disability or might live with more than one and are navigating the world through assistive technology or other augmentations to kind of assist with that with your interactions with the world around you. Meaning folks who live with disability, but also their caretakers,

their loved ones, their friends. All of this relates to the purchasing power of this community. Disability isn't a stagnant thing. We all have our life cycle. As you age, things change, your eyesight adjusts. All of these relate to disability. Designing accessibility is also designing for your future self. People with disabilities want beautiful designs as well. They want a slick interface. They want it to be smooth and an enjoyable experience. And so if you feel like

your design has gotten worse after you've included accessibility, it's time to start actually iterating and think, How do I actually make this an enjoyable interface to interact with while also making sure it's sets expectations and it actually gives people the amount of information they need. And in a way that they can digest it just as everyone else wants to digest that information for screen reader users a lot of it boils down to making sure you're always labeling

your interactive elements, whether it be buttons, links, slider components. Just making sure that you're giving enough information that people know how to interact with your website, with your design, with whatever that interaction looks like. Also, dark mode is something that came out of this community. So if you're someone who leverages that quite frequently. Font is a huge kind of aspect to think about in your design. A thin font that meets color contrast

can still be a really poor readability experience because of that pixelation aspect or because of how your eye actually perceives the text. What are some tangible things you can start doing to help this user group? Create inclusive and user-friendly experiences for all individuals.

User needs refer to the essential requirements users must have met to achieve their goals effectively within a digital product. Wants—though—are the features or experiences users would like to have but aren’t essential for the core functionality. Expectations are the preconceived standards or levels of performance that users believe the product’s going to deliver. Past experiences or market standards are things that often influence these. It’s crucial for designers to really understand the distinction between these concepts so they can prioritize features and create products that don’t just meet fundamental requirements but exceed users' expectations and include desirable elements when possible, too. Of course, accessibility requirements form a fundamental level of expectations for a design to have.

Take our course Emotional Design—How to Make Products People Will Love for essential and in-depth insights into how to design products that users will truly enjoy.

To uncover user needs best, designers should be sure to use a combination of tools and methods. So, conduct interviews and take surveys to collect direct insights from users about their preferences and experiences. Perform observational studies—such as usability testing—to watch users interact with a product and notice unarticulated needs of theirs. Use analytics and data analysis to spot patterns in how people use the product; these offer clues about their needs. This mix provides a full picture of user needs.

Watch as User Experience Strategist and Educator William Hudson explains the significance of user research and various methods involved.

User research is a crucial part of the design process. It helps to bridge the gap between what we think users need and what users actually need. User research is a systematic process of gathering and analyzing information about the target audience or users of a product, service or system. Researchers use a variety of methods to understand users, including surveys, interviews, observational studies, usability testing, contextual inquiry, card sorting and tree testing, eye tracking

studies, A-B testing, ethnographic research and diary studies. By doing user research from the start, we get a much better product, a product that is useful and sells better. In the product development cycle, at each stage, you’ll different answers from user research. Let's go through the main points. What should we build? Before you even begin to design you need to validate your product idea. Will my users need this? Will they want to use it? If not this, what else should we build?

To answer these basic questions, you need to understand your users everyday lives, their motivations, habits, and environment. That way your design a product relevant to them. The best methods for this stage are qualitative interviews and observations. Your visit users at their homes at work, wherever you plan for them to use your product. Sometimes this stage reveals opportunities no one in the design team would ever have imagined. How should we build this further in the design process?

You will test the usability of your design. Is it easy to use and what can you do to improve it? Is it intuitive or do people struggle to achieve basic tasks? At this stage you'll get to observe people using your product, even if it is still a crude prototype. Start doing this early so your users don't get distracted by the esthetics. Focus on functionality and usability. Did we succeed? Finally, after the product is released, you can evaluate the impact of the design.

How much does it improve the efficiency of your users work? How well does the product sell? Do people like to use it? As you can see, user research is something that design teams must do all the time to create useful, usable and delightful products.

This calls for prioritizing based on the product's goals, the impact on the user experience and feasibility. Designers can use techniques such as stakeholder interviews to understand different perspectives, user research to validate the importance of conflicting needs, and design workshops to explore solutions collaboratively. Ultimately, the decision often requires a designer to balance user satisfaction and responsibilities such as accessibility requirements, with business objectives and technical constraints.

Watch our Master Class How To Get People Who Don’t Get Design with Morgane Peng, Design Director at Société Générale for insights into how to bridge the divide between stakeholders and designers.

User needs indeed evolve as technology advances, markets shift and personal preferences change. If they’re to adapt, designers must engage in ongoing research so they understand these changes. Another thing they should do is seek regular feedback from users, so they can capture the users’ evolving needs and preferences. Observing how users interact with products gives insights into areas for improvement. As they iterate on product design based on this feedback and observation, designers can make sure that their products do indeed remain relevant and keep meeting the changing needs of their users.

Take our Master Class Top Ten Things Designers Need to Know About People with Susan Weinschenk, Chief Behavioral Scientist and CEO, The Team W Inc. for insights into users as people.

Ethical considerations are crucial keys to identify and prioritize user needs because they make sure that designers respect user privacy, consent and data security. These considerations keep this kind of harm at bay. Plus, they make sure that fairness rules, especially when it comes to vulnerable populations. Designers must prioritize needs that are in line with ethical standards and societal values—and that often calls for a balance between user benefit and potential risks. Ethical design is a huge issue—one that nurtures trust and long-term engagement as it makes user well-being and societal impact a big priority over short-term gains.

Product Design Lead at Netflix, Nival Sheikh explains the dimension of ethics as it applies to artificial intelligence (AI).

Let's start with a definition about what ethical AI is. What ethical AI does is it seeks to promote fairness, minimize harm and align AI with human values and well-being. And if I'm a designer and I'm working in ethical AI, one of the questions that I really want to ask is how do I design artificially intelligent systems that follow ethical principles and society. When we think about the practice of building AI systems,

ethical AI is that practice that follows ethical and moral standards in society. But it is dynamic, right? As AI changes, ethical AI must change to keep momentum and to keep pace with the advent of AI technology. So one of the big questions that ethical AI asks as a bird's eye perspective of what AI is is what are the legitimate and illegitimate uses of A.I.?

One of the things that we talk about a lot in ethical AI is transparency which basically sounds is exactly what it sounds like. You're allowing users to understand how decisions are made in the AI systems that they're using. So, this and this really what it does is it builds trust with the user and it builds that relationship where it enables the user to really assess how the system behavior (It has a behavior for bias and fairness).

And it really allows them to see, you know, like what's going on in the background when they're using these AI systems. There’s accountability, which is basically that the designers, the developers, the organizations, basically every stakeholder that has some sort of stake in the matter, whether and even users, they should be held accountable for the impact and consequences of AI systems. So this means things like ease of troubleshooting,

ease of understanding, maybe for errors are there how to address those errors. Like those mechanisms should all be included within the system, within the AI system that they're using. And then there's fairness. So, outcomes should be fair and equitable for users. And by mitigating bias and addressing disparities in AI outcomes, this can be achieved. Definitely, easier said than done, as we'll see in a bit.

But this is the whole concept of just making sure that things are equitable and that outcomes aren't biased or favored towards one demographic or one region or one area or person or industry based off of another. or one region or one area or person or industry based off of another. And privacy. So, individuals have rights on their privacy and data, right? Especially we've been through a lot of like consumer data laws. So, the whole concept is built upon like these systems have to be built

to handle user privacy and data in a secure and ethical manner. And information should definitely be obtained consensually, which not only means that, like me, as a user, I'm giving my data and consenting to my data being given. But I also understand what it means to permission a system to to have my data. Like are they going to sell it? What are they going to do with it? I should, as a user, should have a very thorough understanding of that. And so that understanding should be accessible amongst everyone.

That's basically the idea of privacy and ethical AI.

Teams often face multiple challenges with that. These include the ability to understand the diverse needs of various user groups, integrate these needs into a cohesive system design—and manage the technical complexity that comes with advanced features and functionalities. What’s more, it’s vital to make sure accessibility is a reality for all users, maintain data security and privacy, and deal with constraints—such as budget and timelines—as these can complicate the design process. Communication within the team and with stakeholders has to be as effective as possible. Agile and iterative design approaches are key strategies here, too. With them, designers can overcome these obstacles and meet their users’ needs in complex systems and do it successfully.

Watch The Impact of AI on Design with AI Product Designer, Ioana Teleanu to understand more about complex systems and design:

The information volume about AI and design is already overwhelming right now. So, to help me break my own learning into logical categories, I'm always thinking about an intersection of AI and design into two main frames: *designing with AI* and *designing for AI*. When I talk about designing for AI, what I'm talking about is a whole new world of design challenges and opportunities

that we have to navigate when building products in the age of AI. AI interactions in our products require a new way of thinking. And in an article published by Jakob Nielsen, he announces AI as the first new UI paradigm in 60 years. What does this mean? In conventional systems based on command interactions, the user issues commands to the computer one at a time until they reach the desired result, if – hopefully – the system is user-friendly enough to allow people to figure out

what commands to issue at each step. The computer listens to our commands and executes them, hopefully as instructed. In the world of the new AI systems, the user doesn't tell the computer what to do, but instead they tell it the *outcome they hope to achieve*. So, Jakob Nielsen calls this *intent-based outcome specification* and argues that, compared to traditional command-based interactions, this paradigm completely reverses the locus of control.

Where we once ran the machine, now we let the machine run itself. An example would be creating images. Let's say we want to create a digital illustration of a mountain. In a traditional UI system, we'd probably open Photoshop and start adding one instruction on top of the other, draw a triangle, add fill, round corners, add texture, and so on. With AI systems, we go to image generators like Midjourney or DALL-e and instruct it on what kind of image we want to get through prompts: "Draw me an image of a mountain at sunset." And then the computer does the work for you.

So, if you think about it, we'll be designing for a new realm of experiences, completely new user expectations, mental models, and fundamentally different interactions. Many of the traditional products we use are adding AI capabilities. And this is a trend that we will see expand through our product companies. So, it's pretty likely that in the future most of us will have had some sort of experience designing for AI interactions in our roles.

And then, for the second framing, *designing with AI*. I want to start with an idea that has been quite viral on social platforms for the past year. AI won't replace you. A person using AI will. What this means is that AI by itself doesn't hold a power to replace us, mostly because it's infant technology and it holds multiple limitations, some of which are not resolvable in the foreseeable future. For one, it can't figure out what problems to solve yet. AI has trouble understanding context, and because we're still in the age of narrow AI

where AI tools can only do one type of task, it's very hard to solve complex problems with AI alone. It's true that research is being done in the space of collaborative intelligence where under the guidance of a governing AI different AI models work together to tackle more sophisticated tasks and solve complex problems. But right now AI is mostly a one-trick pony, so it can't possibly understand complex systems like a person's context. Their psychology, environment, background, needs, goals,

aspirations, relationships interpret all the connections and understand how they might make this person's life better. Only humans can understand humans deeply enough to really address the problems they struggle with. Then, design solutions require *multi-disciplinary efforts*. Any design solution requires systems thinking making connections between multiple fields and sciences. Understanding interface design, human psychology, information architecture,

visual principles, accessibility design, anthropology and sociology, business strategy, content strategy, user research, and so on. AI systems can't handle this level of complexity in grasping landscapes and putting different perspectives and disciplines together. *AI also lacks empathy and a good understanding of human psychology*. Also, its ability for creativity and imagination is subject to debate. For a long time, I've hated the term "empathy".

I felt it was overused to the point it lost meaning, it became overly diluted. But I believe it's making a spectacular comeback in the age of AI because I personally can't think of a better word that captures what will essentially make us different from computers forever. We have the capacity of imagining and attempting to even feel what the other person feels. Even though computers might mimic a conversational apparent empathy or compassion, computers will never really feel, regardless of how well they'll be able to emulate that.

Also, human creativity and imagination are quite special, even magical I would say. Even though AI can successfully simulate human creativity by putting together existing elements to create something new, in a similar fashion in which people do that, that human special spark comes from imagination: To be able to think of something new. And if you think about it, just looking at AI-generated art will sort of tell you it's been generated by AI.

It's pretty stereotypical; you get the feeling it all looks the same, like something we've seen before. AI still needs a lot of guidance, handholding, and gets lost outside its context. AI can easily go wrong and hallucinate. This is a real technical AI industry term. We've seen some funny and some very worrying examples, but the gist of it is that AI needs us to hold its metaphorical hand. It doesn't perform very well by itself. But even with all these limitations, designers who understand that AI is an opportunity for an exoskeleton

that enhances and augments their natural capabilities will increase their chances of remaining competitive in a market where most of the work will be produced by human-AI collaboration. AI can already support us with making better decisions faster, reducing our cognitive load from having to process large volumes of data, spend time on more meaningful and creative work, kickstart our work projects, artifacts faster, increase the accuracy of our efforts, and so much more.

In the end, there's probably not going to be much escape from AI changing the way we work; so, you might as well prepare to become the person that uses AI to remain competitive.

Designers can do this when they show how user-centered design makes a direct contribution to the achievement of those business objectives. They can present case studies and evidence that shows how an improved user experience really does lead to higher satisfaction, increased loyalty and—ultimately—greater revenue and market share. Designers can also use prototypes and user feedback to make a strong case for the sheer value of user-centered design approaches. Designers can—and should—also make sure that stakeholders are aware of accessibility requirements. When designers get user needs aligned with business goals, they can create a win-win situation—one where both users and the organization benefit.

Watch our Master Class How To Get People Who Don’t Get Design with Morgane Peng, Design Director at Société Générale for insights into how to bridge the divide between stakeholders and designers.

There are several common ones. First, designers might assume they fully understand the user—but don't conduct thorough research—and so they end up with solutions that are based on wrong assumptions. Another thing is to not get a diverse group of users involved in the research phase—and so end up overlooking the needs of certain user segments. What’s more, if designers confuse what users say they want with what they actually need, designers might prioritize features that really don't address fundamental problems.

Designers might also ignore the context of how a product gets used—and miss crucial factors that affect user experience. Last—but not least—if designers fail to iterate based on user feedback, it can keep the refinement of solutions from better meeting the users’ needs. To avoid these pitfalls, designers should engage really deeply with user research, include diverse user perspectives, distinguish between the wants and the needs, consider the context of use—and continuously iterate based on feedback.

Watch Professor of Human-Computer Interaction at University College London, Ann Blandford explain how to approach the interview situation.

As an interviewer, I think it's important to go in with an attitude of *openness*, with an attitude of *wanting to learn*, of *respecting the expertise* of your interviewee, whatever kind of expertise that is, and wanting to learn from them. I sometimes perhaps take that to extremes.

But I think that an important part of interviewing well is to listen to people and not to come with preconceptions about what they're going to say or what they can share. And the other, of course, is about an interviewing style that's open and respectful and *not aggressive* to people so that they do feel relaxed and able to say things and not feel judged for what they're sharing and what they're saying.

So, quite a lot of my research now is around health technologies, particularly. So, that can lead into some fairly sensitive topics. We've done projects looking at how people might use technology to manage their alcohol consumption or their exercise or their diet. And these are all topics that people can feel very defensive about. You know – "How dare you suggest I drink too much or I'm a couch potato or I eat too many carbs!" or whatever.

You know, they're topics where people *can* feel judged. But if people feel judged, then they're not going to give you a real understanding of how you might design technologies that will *really* help them. And so, it's really important to *not* be judgmental – to be open, to respect where they're coming from

and to understand what matters to *them*, as opposed to what you think should matter to them. Well, I certainly work quite hard with students to try to get them to question their own assumptions and not to expose their assumptions when they're interviewing – so that they are actually open to hearing what people are really saying, what people are really trying to express.

Another point is if interviewers are not *intentionally* leading. By coming with too many assumptions about what you're expecting people to care about or expecting people to say, you can unwittingly lead people quite a long way. And leading questions will result in you hearing what you expected to hear, which doesn't necessarily give you the information that you actually need to gain insight from any study.

And surely the point of doing interviews is to get some insight that you didn't already have. If you already knew the answer, there'd be no point in interviewing people about the topic, whatever it is. D.H.: You always have assumptions, right? Otherwise, you wouldn't do a study. A.B.: Yes. D.H.: So, what's the best way to sort of balance or use your assumptions in a constructive way? A.B.: So, I think what you try to do is to have questions more than assumptions.

A *qualitative* study I think is driven by a *question*. *Quantitative* studies are more often driven by a *hypothesis* – i.e. you have a belief and you want to test it – whereas qualitative studies are much more driven by questions. And I've certainly got partway through several studies and suddenly realized that I had a set of assumptions

that aren't necessarily valid. And so, I'm forced to question my own assumptions.

1. Bordegoni, M., Carulli, M., & Spadoni, E. (2023). User Experience and User Experience Design. In Prototyping User eXperience in eXtended Reality (Chapter). SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology.

This chapter offers a comprehensive overview of UX Design—emphasizing its multidisciplinary nature and focus on crafting valuable user experiences. It covers fundamental concepts, methodologies as well as how important a User Centered Design (UCD) philosophy is. The authors outline the UCD's main phases, advocate for user participation and discuss qualitative and quantitative methods employed at each stage. The chapter also debunks the myth that UX Design is solely for digital products, highlighting its application in broader contexts.

2. Manciaracina, A. (2022). How to design learning using technology and users’ needs? In SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology.

This chapter by Andrea Manciaracina delves into designing learning environments that integrate pedagogy, space, and technology. It discusses research outputs and project activities, creating scenarios for learning environments—and proposes a tool for applying these scenarios in real-world teaching. The tool—validated through co-design activities with teachers from Politecnico di Milano—aims to help users select appropriate technologies for teaching. The chapter ends with a rule manual for the tool—combining methodological insights from research and practical findings from tool experimentation.

Norman, D. A. (2013). The Design of Everyday Things [Paperback – Illustrated]. Basic Books.