In the past, designers often reported to marketing managers and were neither expected nor allowed to make business decisions. When traditionally-structured companies transition to a design-driven mindset, there can be friction between the marketing and design teams. Let’s take a closer look at this conflict and what you can do to resolve it.

In the 1970s, Nestlé was among the many multinational companies that were keen to woo Japanese customers. And while other international brands saw growth in sales, Nestlé’s coffee didn’t.

Nestlé had a great product. Their target audience liked the taste of their coffee. And it was affordable. But that didn’t translate to sales. To identify the reason for this mismatch, the company got help from an anthropologist and market researcher, Clotaire Rapaille.

Rapaille interviewed groups of people and asked them to associate childhood memories and emotions with different types of products.

He found that his participants had no emotional attachment to coffee.

For thousands of years, tea has played a major part in Japanese culture. For Rapaille’s study participants, tea was the taste of social gatherings and happy memories, not coffee.

Nestlé took these observations and decided to imprint positive emotions into children. They did this through candy. And so, children in the ‘70s learned to enjoy the taste of coffee-flavored candy.

Fast-forward a couple of decades. Nestlé’s coffee-flavored-candy-loving customers had entered the workforce. And they worked long hours. The company re-introduced the beverage. This time around, coffee sales took off. And since then, Nestlé has dominated the Japanese coffee market and become a case study in long-term business and marketing strategy.

Is this method of imprinting coffee into the culture through children and teens ethical? We’ll get to it a little later.

First, let’s take a step back and understand how traditional businesses functioned at the time.

Design as a Function of Marketing: The Marketing Mix

In a traditional business structure, the marketing department was responsible for four types of decisions: product, price, place and promotion. Collectively, these are called the marketing mix, and are often abbreviated to the 4Ps:

Product: A product is anything that can be offered in the market, that satisfies a customer’s need. It can be a material object, a service, or a combination of both.

Price: The marketing team decides the price based on what it costs to manufacture and/or deliver the product, what customers are willing to pay, government restrictions and what the competition is like.

Place: Also known as distribution, this includes decisions related to how customers can acquire the product — in company-owned stores or via direct sellers or third-party distribution channels such as supermarkets.

Promotion: Often the most visible aspect of the marketing mix, promotion relates to all aspects of communication. Advertising, promotional offers and press coverage are some of the components of promotion. Together, these create the perception of a brand and the values the brand stands for.

First introduced in the 1960s by Edmund Jerome McCarthy, a marketing professor, the marketing mix is a collection of decisions related to the product, its price, where to distribute it (place) and how to communicate with customers (promotion).

© Ryan Van Etten, CC BY 2.0

An extended version of the marketing mix, the 7Ps, includes the original decisions along with service-related decisions:

People (those who deliver the service);

Process (the flow of activities involved in the service); and

Physical evidence (the environment in which the service is delivered).

As per the marketing mix, marketers relied on designers to make products more “marketable”. The role of design was to create products and offer support services within the larger function of marketing. Product designers relied on market researchers for insights about the customers. And all designers reported to marketing managers.

In Nestlé’s case, the marketers decided to adopt strategies to push an existing product into a market. They focused on selling the product.

A design thinker would have advocated a different approach — focus on the people, and create value based on the customers’ needs, and pull customers towards the product.

Changing the Status Quo: Shifting the Focus to Customer Journey

Marketers viewed designers as creative people who didn’t understand how the business worked. Designers, on the other hand, felt frustrated that they had no say in business decisions. All they could do was watch, as decisions outside of their control had a cascading impact on the customer’s experience.

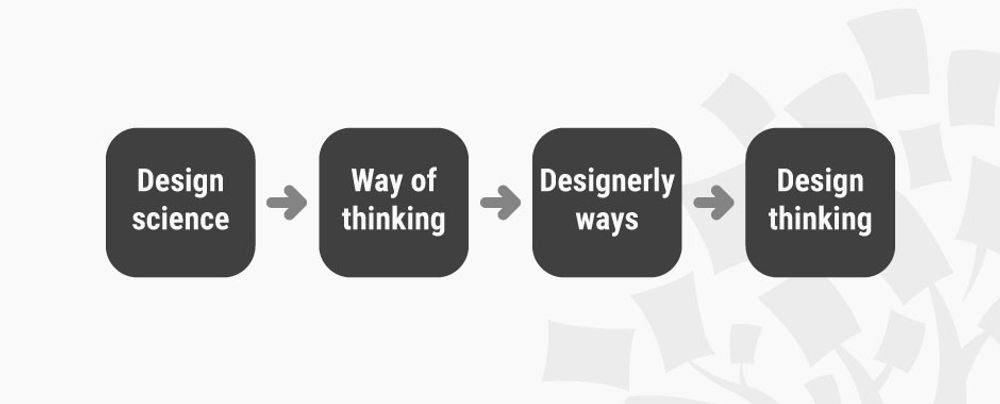

Designers had long advocated a “seat at the table” — the authority to make business decisions. Thanks to Apple, they got a shot in the arm. First with the iPod, and then with the iPhone, Apple disrupted not one, but two industries (music and smartphone) outside their core domain (computers). The reason for their success wasn’t just good design or great marketing, but also a focus on the entire journey of the customer.

How the iPod Disrupted the Music Industry

The iPod was essentially an Mp3 player. And there were many Mp3 players in the market. Companies differentiated their Mp3 players based on size and the storage capacity of those devices — the product.

Apple focused on its users. People wanted to listen to music. The iPod made it easier to listen to music than other Mp3 players did. Here’s how Apple eliminated all the barriers to listen to music:

Focus on listening to music: At the surface, the simple, sleek form factor brought full attention to the purpose of the device — to play music. What set it apart was the ability to quickly transfer music to the iPod; something that took hours on other Mp3 players (via a basic speed USB), could now be done within minutes.

The product solves the problem of transfer speed.Get hold of favorite songs: With the introduction of iTunes, people no longer had to purchase whole albums (at that time, still in the form of CDs) to hear their favorite single. They could buy individual songs for 99 cents.

The companion service and price solves the problem of inflexible purchase options.Get music, fast: Once they had purchased the song, listeners could download it instantly.

The digital place allows the customer to listen instantly.

Not only did the device change the way people listened to music; it also changed the way the music industry operated — from whole albums to individual songs, and from owning music, to owning the right to play music.

How the iPhone Changed the Smartphone Industry

Just like the iPod, the iPhone wasn’t the first smartphone. The smartphones at the time used to be business phones, meant for top executives. The iPhone made smartphones friendly to use and put powerful computing within the palms and pockets of everyone.

Let’s take a look at how Apple took care of all components of its customers' journey:

Discovery: Customers first heard about the product through Steve Jobs’ storytelling and unique presentation style, emphasizing a focus on design and usability (promotion).

Acquisition/purchase: Customers saw and held the device for the first time inside the aesthetically designed Apple stores, which were designed to put the focus on the product, and had friendly staff (place and physical evidence).

Product usage: The iPhone had an intuitive device and a plethora of Apps to help customers perform several tasks, including making phone calls, listening to music and taking pictures (product).

Customer support: When customers encountered a problem, the Geniuses at the Genius Bar helped them with their queries and repaired the product, as needed (people).

Continued engagement: The App Store encouraged third-party app developers to build upon their platform and launched their “There’s an App for that” campaign — creating an entirely new mobile app industry, which in turn helped solve other problems that customers faced.

The iPhone experience began well before the purchase itself. The Apple Store on New York’s 5th Avenue, with its giant glass cube, is as much a part of the experience of owning an iPhone.

© Pixabay, CC0

With both the iPod and the iPhone, Apple took control of every aspect of the customer’s journey. Well, almost. The company decided to allow third-party developers to create apps for distribution through its App Store. To ensure that Apple customers still had a good experience, the company created strict design guidelines and set up an approval process for all apps submitted to the store.

A side effect of this was that the App Store became a platform for others to launch their businesses.

Apple’s strict guidelines for app design act as a handy resource for those launching their mobile apps, and ensure that customers have a streamlined experience with third-party apps as well.

In Apple’s holistic view of the customers’ journey, the lines between design and marketing are blurry. The age of design-led businesses and design thinking had arrived.

Users vs Market

Soon after Apple’s successes, companies across different industries hired designers and acquired design agencies. From soft drink companies to banks, everyone wanted to incorporate design into their corporate culture. Retrofitting existing organization structures with design thinking, however, isn’t as easy as acquiring design agencies, particularly when design thinking and marketing appear to have a lot in common.

Marketers, who traditionally managed designers, did not see why they should let designers be in charge. To them, design thinking was just a glossy version of age-old marketing concepts. And why not? Here’s how the American Marketing Association defines marketing:

“Marketing is the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large.”

— The American Marketing Association

That definition sounds very similar to design thinking. The difference is in the details. Here are some of them.

Research-driven

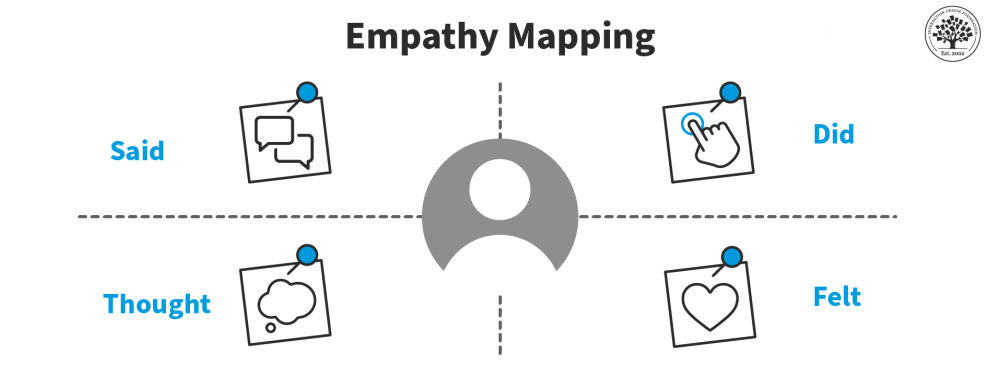

Both design thinking and marketing are research-driven. They seek to understand customer behavior. Personas, surveys, focus groups, interviews and field trials are among the many research tools common to both.

Design thinkers create user personas to understand the individual user(s) and create solutions with the user(s) in mind; marketing seeks to understand how many of such buyers exist in the market. Marketers look at aggregates and numbers, while design thinkers look for meaning and motivation within those numbers.Individuals liked Nestlé’s coffee. There just weren’t enough people who wanted to buy it.

Many people owned Mp3 players, but that didn’t mean they were happy with their experience.

Aim to influence behavior

Both designers and marketers seek to influence behavior. Design thinkers explore problems and test solutions to see if users will use them in their context. Marketing takes these solutions and tests to see if users will buy them. In both cases, users/buyers will change their existing ways and means of accomplishing their tasks and goals.Nestlé made the Japanese fall in love with coffee.

iTunes fundamentally changed how people bought music.

Fulfill customers’ needs, at a profit

Both design thinking and marketing seek to fulfill customer needs — both stated and unstated. While design thinking approaches it with the user first, marketing approaches it with the business first.No one asked for a coffee-flavored candy, and no one asked for an iPhone. But once they were introduced, people loved them.

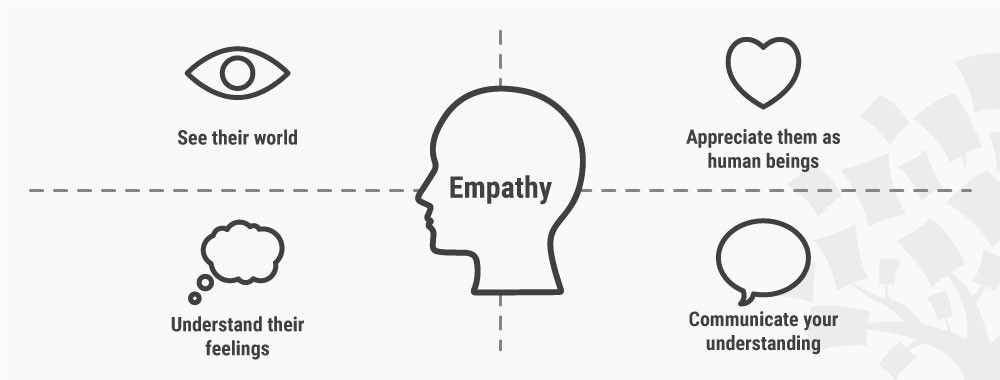

The Customer Journey: Integrating Design and Marketing

Design thinking and marketing have the same overarching goals — delight customers at a profit. They often use the same tools to understand customers. The difference is in perspective. Bringing the two teams to work together will strengthen both the product and the brand, resulting in happy customers and bigger profits.

Break the Silos

Design thinking calls for a multi-disciplinary team to work on understanding and solving problems. Instead of focusing on each team member’s skills and expertise, the team focuses on the customer’s journey.

Customer journey mapping is particularly helpful in establishing a common understanding between different team members. It highlights the disconnect and the gaps in the customers’ experience with the company’s offerings. Once the teams identify the gaps, they share a common goal: to turn those gaps into opportunities to improve the customers’ experience. These opportunities can relate to any aspect of the business — an improvement in the product, a tweak to the communication or the introduction of an entirely new value proposition.

When teams work together, they draw upon each other’s expertise and insights and avoid conflicts and misunderstandings.

Use a Common Research Team

As with the customer journey mapping exercise, a common research team for user and market research will help keep both designers and marketers on the same page. What’s more, it prevents duplicate efforts and brings cost savings to the company.

Build a Single Narrative

The end user/customer doesn’t care about a company’s internal hierarchy or structure. If different aspects of their experience speak different languages, the end user’s journey suffers.

Marketers and designers can collaborate and create a common brand vocabulary. For example, designers can match the tone of the onboarding messages within the UI of a mobile app with that of the brand’s advertisement campaign. Similarly, marketers can create promotional strategies that highlight how the product solves customers’ pain points (instead of being “better” than everyone else).

Collaborate Within, and Beyond

Businesses come in all shapes and sizes. When you look at the customer’s journey, you may find that some aspects of that journey are beyond your company’s resources. In such a scenario, teams can look for partners outside the company, and work closely with them to deliver great experiences.

After you abolish the internal silos, turn vendors and distributors into partners and work together towards a shared goal — the end customer’s experience.

Let’s return to Nestlé for a moment. To build the market, Nestlé introduced a new product — the coffee-flavored candy. Indeed, were it not for a great product (the candy) they couldn’t have built a market. No amount of marketing can make a bad product viable. And conversely, no matter how good a product may be, poor marketing will prevent it from becoming profitable.

While Nestlé’s coffee was struggling in the ‘70s, a UK-based brand, Rowntree, introduced a bar of chocolate that became an instant hit. Like coffee, chocolate also had yet to make a significant impact on Japanese culture and taste preference. What spurred its sales, was the name of the brand: KitKat.

Globally, KitKat is synonymous with the phrase, “Take a break.” In Japan, the name closely resembles the Japanese phrase “Kitto Katsu”, which roughly translates to: “You will surely win.” Because of this positive connotation, customers in Japan sent KitKats as gifts to students appearing for University examinations, as a lucky charm.

Nestlé acquired the brand from Rowntree in the 1980s.

About 30 years after the study that helped it introduce coffee in Japan, it was Nestlé’s turn to adapt to Japanese culture.

Care to mail a KitKat?

© Copyright unknown.

In 2009, the company partnered with Japan Post to launch the postable KitKat. People could now mail KitKats to wish students well before their examinations. And to cater to Japan’s palette, KitKat is offered in over 300 different flavors — their most popular ones being Strawberry and, yes, Matcha Green Tea.

The story of Nestlé in Japan began as one of pushing coffee to a new market. With KitKat, it became one of adapting to the local culture and pulling customers. While this pull began with sheer luck, the company capitalized on it and modified its product to cater to the unique tastes of the market. It incorporated the green tea flavor in its product and collaborated with the postal service to make the customer’s journey seamless.

A Note on Ethics and Brand Activism

We began with Nestlé’s method of targeting children and teens to build a market.

Many software companies also use a similar strategy — they partner with schools and educational institutions so that students develop a preference for their applications. We could argue that these examples are harmless. But the ethical implications of the underlying tactic can quickly escalate to something more sinister — such as selling e-cigarettes to teenagers.

Designers are just as guilty of unethical practices as marketers and businesses. Many digital platforms use dark patterns that trick users into purchasing something or giving away information. Examples include in-app purchases in children’s games and Facebook’s privacy settings.

No matter what our role in the organization, it is our responsibility to behave ethically. If not for the benefit of society at large (and ourselves, lest we be at the receiving end of our tactics), consider the implications of unethical practices on profits.

For years, unethical business practices were tackled by consumer groups and activists, often with limited resources. With lobbying might and a much larger resource pool on their side, companies could get away with questionable business decisions.

Research has revealed that millennials and Gen Z are more likely to support brands that support causes they believe in.

© Markus Spiske, CC0

Unlike in the past, however, today’s consumers have platforms to voice their opinions. Bad press travels fast, and can quickly translate to widespread calls for a boycott and/or government regulation. It is due to such public pressures that the European Union passed the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that sets the guidelines for the collection and processing of personal data.

Proactively listening to customer sentiment and factoring it into business is more important than ever. This has also spawned another dimension to business: brand activism. When done right, it can be positive, not only for society but also for sales.

In the words of Philip Kotler and Christian Sarkar, “stakeholders around the world, especially millennials, now expect businesses to engage in progressive brand activism.” Brands must stand for something, even if it means antagonizing another section of their customer base.

In a survey conducted by BRANDfog and McPherson Strategies, 93% of respondents agreed with the statement: “When CEOs issue statements about the key social issues of our time and I agree with the sentiment, I am more likely to purchase from that company.” A total of 86% of people thought that CEOs who publicly defend the rights of others on social media are seen as great leaders.

Over the years, more companies have been taking public stands on social issues. In 2019, a group of CEOs of major companies issued a statement on “the purpose of a corporation” during the Business RoundTable and redefined the core values of businesses. They stated that companies should no longer advance only the interests of shareholders. They must also invest in their employees; protect the environment; deal fairly and ethically with their suppliers; and support the local communities that they are a part of.

Many companies have pledged to switch to new or renewable energy sources and source their raw materials ethically, in response to concerns about unsustainable and unethical business practices. These decisions are not directly related to the customers’ journey but may influence the product — impacting the source of inputs, or directly affecting a product’s feature set.

The Take Away

Design thinking and marketing are two sides of the same coin. Both aim to fulfill customer needs at a profit, but from different sides.

Customers interact with the brand in many ways. At each touchpoint — be it the product, the advertisement or the privacy policy — companies need to speak the same language.

In our digital age, when the lines between product and service are blurred, where the barriers to entry in the digital space are fewer, and in which the customer’s voice speaks the loudest, teams in a company cannot afford to work in a traditional siloed way.

When you work as an integrated, multi-disciplinary team and focus on the customer’s journey, you can build a strong narrative for the benefit of customers as well as the business.

Customers, especially millennials and Gen Z, now expect brands to take a stand on issues, and proactively engage in activism. As a result, not only must teams work together to cater to the customer’s experience, but they also need to take a moral stance on geo-political and socio-cultural issues.

References and Where to Learn More

Learn more about design thinking in our course, Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide

Watch Jakob Nielsen make the case for integrated research teams (~3 minutes) here:

Can Market Research Teams and UX Research Teams Collaborate and Avoid Miscommunication?

Tim Brown walks through his transition from a designer to a design thinker in this TED Talk (~16 minutes):

Designers -- think big!

Read more about Nestlé’s coffee strategy in Japan:

Nestle Hired a Psychoanalyst to Convert a Nation to Coffee

With the iPod and iTunes combination, Apple disrupted not just the market for Mp3 players, but also the music industry. Here’s more on how they did that:

How iTunes changed music, and the world

Images

Hero Image: © Christina Morillo, CC0