One of the most important steps in the design thinking or human-centered design (HCD) methodology is to define the users' problems. This means to clearly identify and articulate problems in the UX so that you can later begin the ideation process (i.e., generate great ideas on how to solve said problems). Task analysis is a simple exercise that UX designers can undertake during the definition of a problem, which can help identify opportunities to improve and generate some preliminary ideas as to how you might approach these challenges. Let's find out how.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

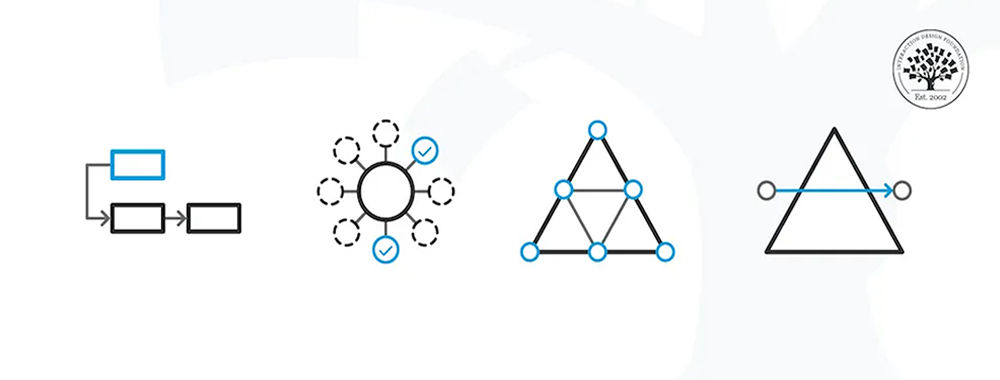

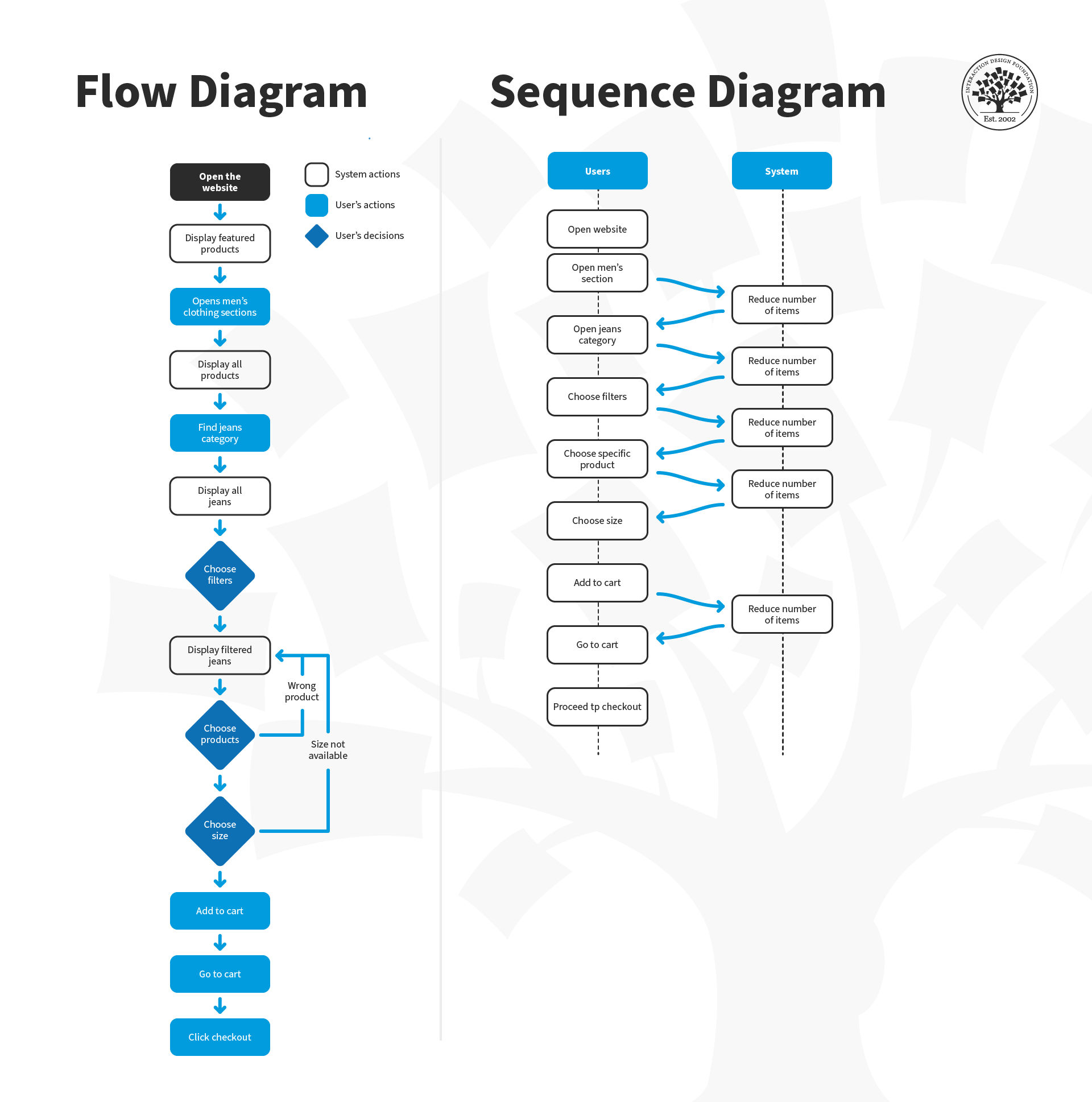

Task analysis is a method that helps you understand how users accomplish their goals and the steps they take to get there. This establishes their mental models and is crucial for task-oriented design. The most common output of a task analysis is a diagram that outlines the user's actions and the system's responses.

Designers can use this diagram to identify areas where additional support may be needed or to eliminate unnecessary steps. For example, designers may automate certain actions that users currently perform manually.

You can approach a task analysis activity from two main viewpoints:

Hierarchical Task Analysis: Consists of breaking down tasks into smaller sub-tasks.

Cognitive Task Analysis: Focuses on tasks that require decision-making, problem-solving, memory, attention and judgment.

How to Prepare for a Task Analysis

Usability experts agree that task analysis is an important activity where designers must understand the users and their environments, their goals and external factors that might influence the performance of the task. This means that you may have already engaged in user research, which provides you with outputs such as user personas, scenarios or storyboards. This data is essential for task analysis, as you will base your work on these outputs.

To ensure an effective task analysis process, it's essential to gather focused data during user research. Cognitive scientist and UX consultant Larry Marine suggests collecting five types of data during this phase:

Trigger: What initiates the task for the user?

Desired Outcome: How will users know they have successfully completed the task?

Base Knowledge: What will the users be expected to know when starting the task?

Required Knowledge: What do users already know before starting the task?

Artifacts: What resources or tools will users require during the task?

How to Conduct a Task Analysis

With your current information, you can sketch out how a user goes about their daily life by mapping out the sequence of activities required to achieve a goal. Before you start, it's important to have an overview of the process and its steps to prepare better.

Here is a step-by-step guide for conducting task analysis:

Identify the Task You Need to Analyze: Pick a persona and scenario for your user research and repeat the task analysis process for each of them. What is that user's goal and motivation to achieve said goal?

Break Down This Goal into Smaller Subtasks: A good rule of thumb is to aim for 4–8 subtasks – any more than this may indicate that the goal is too broad or abstract.

Draw a Layered Task Diagram of Each Subtask: You can use any notation you like for the diagram since there is no real standard here. Larry Marine shares some constructive advice on his notation, which you will examine below.

Write the Story: Ensure you accompany your diagram with a narrative that focuses on the whys.

Validate Your Analysis: Review the analysis with someone who wasn’t involved in the breakdown but knows the tasks well enough to check for consistency.

Pro Tip: Conduct a parallel task analysis with more than one person to undertake the process simultaneously so that you can compare and merge outputs into a final deliverable.

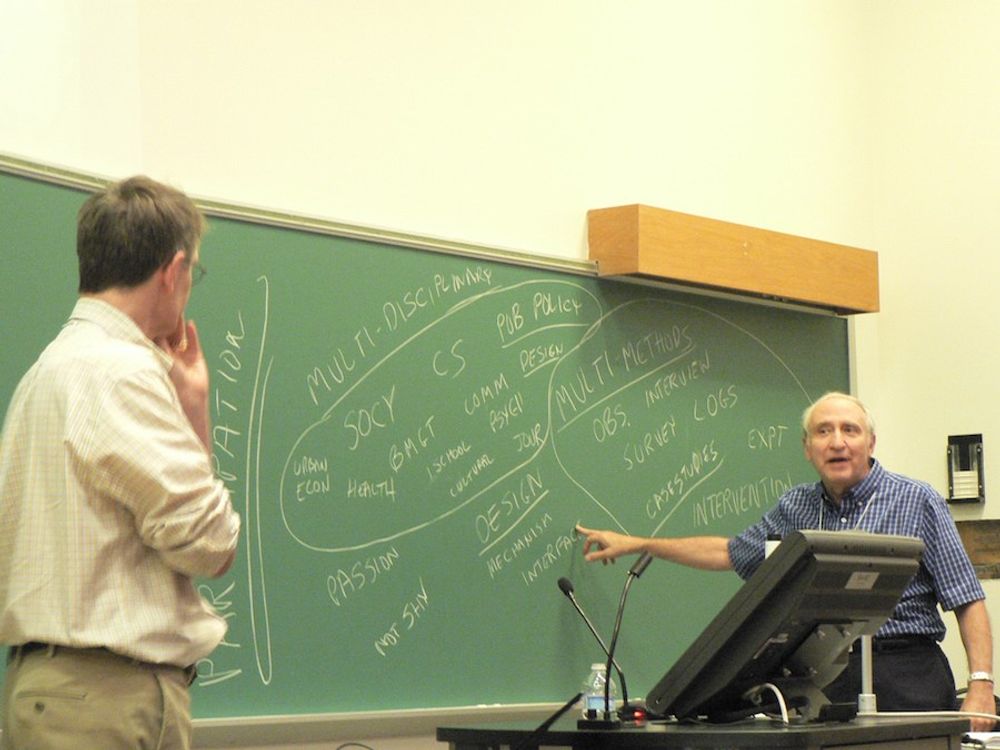

Larry Marine likes to annotate his task analysis diagrams using different colors in the various flows; for example, green represents users' actions, yellow is a step the system can do, purple represents tools or knowledge, and orange represents questions about the task.

Larry Marine suggests adding annotations to task analysis diagrams using a variety of colors that correspond to different flows. This technique helps him better visualize the user's journey and identify pain points or areas for improvement in the user experience.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

A task analysis would probably have a greater proportion of "green" flows initially. A redesigned task would probably have fewer "green" and more "yellow" flows to show that you've really managed to off-load tasks from a user to a system, thus improving their overall experience to make their lives easier.

Download and share this guide on task analysis with your team to collaboratively visualize your user's journey and identify pain points.

The Take Away

Task analysis is a vital tool in a UX designer's skill set, as it helps designers understand how users complete tasks and identify areas for improvement. However, it's important to keep the user's perspective in mind and resist the temptation to generate your own interpretations of the problem or stick to design elements just for the sake of it.

To ensure that task analysis is effective, it should be backed by rigorous user research. Without data from user research, any efforts to proceed with task analysis will be blind and may not reflect actual user needs. Remember that task analysis is not a one-off process. Designers may need to repeat task analysis on their own designs later in the process.

Finally, task analysis requires time, resources, people, and budget like any other UX design activity. Balance these requirements carefully and engage in the process only if you have sufficient amounts of these elements.

References and Where to Learn More

Read these books about Task Analysis and other related concepts:

Task Analysis. Human-computer interaction: Development Process. Catherine Courage, Janice (Genny) Redish, and Dennis Wixon. 2009

Task Analysis: How to Develop an Understanding of Work (Users' Guides to Human Factors and Ergonomics Methods). Jack Stuster. 2019.

Check out this in-depth article about Hierarchical Task Analysis from UX Matters.

Follow Larry Marine’s excellent approach to Task Analysis.

Learn about Task Analysis and usability from the Usability.gov website.

Hero Image: © Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0