Ideation for Design - Preparing for the Design Race

- 865 shares

- 5 years ago

Ideation is the creative process UX (user experience) designers use to generate a wide range of ideas that solve user problems. You use it with your team to move beyond the obvious and explore potential solutions in depth. Then you choose which ideas to develop further through prototyping and testing. With structure and collaboration, ideation helps you identify the most effective solutions to correctly defined problems.

Explore the five phases of the design thinking process here, and how this flexible, iterative design process drives innovation you can count on.

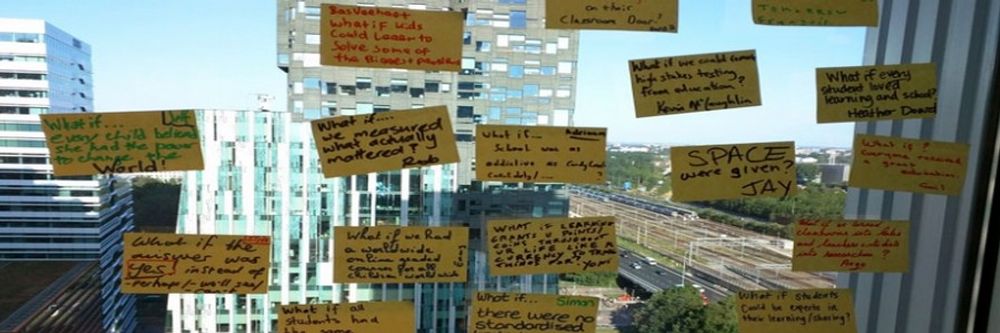

Hasso-Platner Institute Panorama

Ludwig Wilhelm Wall, CC BY-SA 3.0

Ideation may sound self-explanatory, almost too obvious and “organic” a stage in the UX design process to approach with an analytical mindset. However, it’s virtually impossible to overstate its importance. One reason is the misconception that great ideas “just happen.” Although wonderful notions can sometimes come from “out of the blue,” a deliberate approach is best.

Use this step-by-step approach to get the most out of your ideation sessions.

Before you start ideating, you need to know the design challenge and what’s involved. Make sure you’ve got:

A clear problem statement or “How might we…” question that you have rooted in user insight and design constraints: for example, “How might we help remote workers feel connected through our collaboration tool?”

A shared understanding of user needs, pain points, and context. For this, it’s wise to create some personas (research-based representations of real user groups) you can empathize with and plug into your design process.

In this video, William Hudson: User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd., explains how personas help you keep real users at the center of your design process.

Established constraints, such as technology, business goals, brand, and budget, so your team can push creativity within realistic boundaries to rein in the more extravagant ideas you might generate at first.

In this video, William Hudson explains how clearly identifying constraints early, including requirements like accessibility compliance and data encryption, helps you frame the right problem and avoid costly rework later in development.

A prepared space, facilitator, materials (whiteboard, sticky notes, markers), and a mindset that fosters open generation of ideas.

In terms of “venue,” you might run in-person workshops (with sticky notes, whiteboards); remote sessions (using digital whiteboards); individual sketching or silent idea generation followed by group sharing; or contextual ideation (in the field, or using roleplay, bodystorming, or scenario creation).

You’ll want structure and rules to serve a key part in ideation, though not to stifle creativity. So:

The facilitator should explain rules like: “No idea is too wild,” “Go for quantity over quality,” “Build on each other’s ideas,” “Avoid off-topic tangents,” and “Suspend judgment.” You need a judgment-free environment, so encourage wild ideas first, and then let them evolve into more realistic solutions.

Decide on a length for the ideation session, such as 30–60 minutes.

Orient the group with a warm-up exercise if they need to break the ice, and remind everyone to keep an open mindset.

Provide materials for in-person sessions, like sticky notes, markers, and sketch pads.

Select one or more ideation techniques that fit your team and challenge, including:

Brainstorming: This classic verbal idea sharing approach can work wonders in a group.

In this video, William Hudson explains how to run an effective brainstorming session that sparks creativity and collaboration.

Brainwriting / Brainwalking: In these brainstorming variants, participants write down ideas, pass them on, or rotate between stations.

Crazy eights: Each participant folds a sheet into eight panels and quickly sketches eight ideas in eight minutes.

Mind-mapping: Write a keyword in the center and draw branches of associated ideas, then connections between them. It’s useful for exploring a large idea space.

Bad ideas: Encourage everyone to come up with bad ideas deliberately, to discover what makes them “bad” and find useful insights. You’ve also got the worst possible idea approach, where you invite the group to propose hilariously bad solutions and then flip them into useful ones. The weirdest, wildest, and worst ideas can help break inhibitions and reveal hidden directions to optimal design destinations.

In this video, Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University, shows you how deliberately creating bad ideas can spark unexpected creativity and lead to innovative solutions.

Bodystorming / Roleplay: Physically act out the scenario or simulate the environment to spark ideas. It’s a famously useful technique as it helps team members get closer to empathize with users as they can feel more what it’s like to be them.

In this video Frank Spillers: Service Designer, Founder and CEO of Experience Dynamics, shows you how bodystorming and role play can help you experience user interactions firsthand.

You can combine techniques in one session, such as mind-mapping and then crazy eights, for example.

Even ideas that feel silly or irrelevant might spark a later insight, so don’t let them get away. Capture all ideas on sticky notes, digital boards, or whiteboards. Document who said what, if needed, and keep a photo or export of the board so the resource is there to tap. You might have some “diamonds in the rough”; don’t overlook them.

Once idea generation slows, you’ll likely have explored most, if not all, of what you can. The strength of divergent thinking means you should have a wide variety of ideas, so now it’s time to switch to convergent thinking and look at what you have and sift and sort it all to find useful ideas.

So, move into a clustering or affinity-mapping activity: group similar ideas, identify themes, merge duplicates, and highlight interesting directions. Begin narrowing toward feasibility and alignment with constraints so you can filter ideas that are creative and feasible.

Find valuable insights as this video explains how affinity diagramming helps you organize and cluster ideas to uncover key patterns and insights.

Pick one or more ideas to develop further, in the prototyping and then testing stage. Use criteria such as user value, business viability, technical feasibility, and uniqueness. Store other ideas for future use; not all ideas will be viable right now.

Once you’ve selected promising ideas, hand them over to the team for prototyping, storyboarding, sketching or wireframing. Early prototyping empowers you to quickly find answers about your idea for a possible design solution. From testing it with users, you’ll come away with essential insights as to what works and what doesn’t. Note that ideation doesn’t stop here; you may repeat the process as you test and learn.

Explore how prototyping and iteration help you refine designs through user testing and continuous improvement in this video with Alan Dix.

Ideation represents a crucial transition: a bridge from user research and problem definition into solution exploration. Here are some key reasons why good ideation matters.

When you deliberately widen your thinking and approach it as a dedicated activity, you create space for unexpected, creative responses to user needs. First, concentrate on idea generation itself and mentally “go wide” in terms of concepts and outcomes. When you adopt effective ideation techniques, you can challenge assumptions you might not realize you have. From there, you can access new angles to examine the problem and surface valuable insights on where to go for a solution.

Because ideation follows design thinking’s empathize phase (where you research your target audience to understand their user needs and more) and define phase (where you isolate and define the right problem these users face), the ideas you generate remain grounded in real user needs rather than personal preferences or technology hype. With that alignment, target users will more likely find your solution meaningful and usable. For even the most complex problems, ideation often can help crack the “code” you need to determine what users really want, not what you (or they) think they might want.

Ideation helps you keep the door open so you can explore many paths without committing resources to detailed designs. One of the dangers of design work is that design teams can jump to conclusions based on assumptions or go along with the first promising-looking idea. However, when you ideate you can think ahead without making commitments and avoid wasted time or effort on ideas you end up not using.

Running ideation workshops makes great sense. It fosters cross-disciplinary collaboration, engages people from different backgrounds and skill sets, brings in diverse perspectives, and helps team members align around possibilities rather than just technical or business constraints. Ideating with other teams, such as marketing, development, and business stakeholders, can stoke the “fires” of creativity tremendously. You can light your way to examine the true problem more fruitfully, and from more angles, and find the best viewpoint on what’s needed in a solution.

The output from ideation becomes the input for you and your design team to advance to prototyping and experimentation in the best direction. From the many ideas you’ll likely generate in divergent thinking, where you push the limits to explore a vast array of possibilities, you then narrow your focus on the most promising options in convergent thinking. And through further refining at this stage, you can find great ideas to prototype and test if they’re valid.

In this video, Alan Dix explains how divergent and convergent thinking work together to turn creative ideas into practical design solutions.

Overall, treat ideation not as an exercise in “we generated ideas” but “we selected ideas to explore.” Like myths about creative individuals, misconceptions about ideation may lead some people in the organization, especially business stakeholders, to misread it as an excuse to waste time under the guise of “creativity.” Nothing could be further from the truth. Blue-sky ideation can cover almost innumerable angles before you zero in on promising contenders. Plus, the team-building in ideation sessions enables groups to gel together around a common goal of participation and team-ownership of a golden opportunity.

Perhaps best of all, because ideation is not a “one-and-done” activity but circular, you and your team can re-explore new avenues as you move back and forth in your design process. The right solution is out there, waiting for you. You may unwittingly find the doorway to it and won’t realize it at first. Or it might just take a fresh ideation effort to push into that section of the vast idea space and lock onto the “coordinates” of an exceptionally powerful solution. From there, you can bring it down to “street level” and fine-tune your way to serving up a truly innovative and successful digital solution, one which users will love your brand for delighting them with.

Explore a vast realm and tap powerful design potential in our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

Enjoy a wealth of insights, tips, and more in our Master Class Harness Your Creativity to Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author and Creativity Expert.

Discover many valuable insights in our article What Does a Creative Designer Do? and find out the answer and much more.

Head right into some helpful avenues in our article Three Ideation Methods to Enhance Your Innovative Thinking.

Start ideation once you’ve clearly defined the problem based on user research. This typically follows the discovery and synthesis phases or empathize and define phases in design thinking. By then, you’ll understand your users’ needs, behaviors, and pain points, which empowers you to engage in meaningful idea generation. Ideating too early risks solving the wrong problem.

Once you’ve crafted problem statements or “How Might We” questions, you’re ready. This timing aligns with the double diamond model, where ideation happens in the second diamond, after discovery and definition. Solid research enables designers to generate targeted, innovative solutions. UX (user experience) design teams who ideate with a strong research foundation often create more relevant, user-centered products; so, before sketching or brainstorming, ensure the insights are in place to guide your creative process.

Explore how to empathize to kickstart your creative process with solid insights you can build upon.

UX designers use a variety of ideation techniques, each suited to different goals. The most common include brainstorming, where teams rapidly generate ideas without judgment; mind mapping, which helps visually organize thoughts and relationships; and Crazy 8s, which pushes participants to sketch eight ideas in eight minutes on the eight “panels” of a folded sheet of paper. SCAMPER is another favorite, which prompts designers to think differently by asking how to Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, or Reverse elements of a solution.

Storyboarding visualizes user experiences step-by-step, while sketching helps express rough concepts quickly. These methods encourage diverse thinking, collaboration, and speed. UX teams often mix multiple techniques during a single session to keep creativity flowing and cover more ground. Each method helps break away from conventional ideas and promotes user-centered innovation that can produce highly creative wins for users and brands.

Tap the immense power of brainstorming to unlock otherwise-hidden avenues that can bring powerful insights about users and what they want from design solutions.

To run a successful ideation session, start with a clear goal and set of “How Might We” questions. Invite a diverse group of participants to encourage varied perspectives. Create a safe, judgment-free space so that everyone feels comfortable sharing ideas.

Use time-boxed ideation activities like brainstorming or Crazy 8s to keep energy high and ideas flowing. Capture all ideas visually using sticky notes or digital whiteboards. Keep discussions focused, and if energy dips, introduce a creative exercise or short break.

After ideating, cluster similar ideas and vote on favorites using methods like dot voting. Above all, facilitate, don’t dominate; your role is to guide, not control. A well-structured session fuels innovation and ensures every voice contributes to truly user-focused solutions.

Get right into the role of facilitator and come away with valuable insights in our article What is Ideation – and How to Prepare for Ideation Sessions.

When ideating solo, structure your time like a team session. Don’t worry; you don’t have to pretend others are there. Instead, begin with a clear problem statement or “How Might We” question. Use methods like mind mapping, sketching, or journaling to explore ideas.

Try the Crazy 8s technique (sketching 8 ideas in 8 minutes on a sheet of paper folded 3 times to make 8 sections); it still works solo and forces quick thinking. Approaches like SCAMPER help shift your perspective and generate unique solutions. Talk aloud or record voice notes to simulate dialogue and spark new thoughts.

When ideas stall, take a walk or switch environments to reset. Reflect on past projects or competitors’ designs for inspiration (but don’t copy). Most importantly, externalize your thinking; don’t just brainstorm in your head. The act of writing or sketching makes ideas real and helps refine them. Solo ideation offers deep focus and freedom from groupthink, powerful plusses that can lead to creative, user-centered outcomes.

Dig deeper and come away with golden insights from our article Define and Frame Your Design Challenge by Creating Your Point Of View and Ask “How Might We.”

Crazy 8s boosts ideation speed and variety by challenging you to sketch eight ideas in eight minutes. Start with a well-defined problem or “How Might We” question. Fold a sheet of paper into eight sections (so fold the sheet three times). Set a one-minute timer for each sketch; keep it fast and rough. Don’t aim for perfection; focus on quantity and creativity.

Crazy 8s breaks mental blocks by forcing rapid thinking and pushing past obvious solutions. It’s something teams often use early in design sprints to spark diverse ideas. After sketching, share and discuss the concepts if working with a team, or review them yourself to identify patterns. You can mix it with dot voting to prioritize ideas. Crazy 8s keeps ideation fresh, visual, and energizing, and it’s perfect for UX challenges that need a creative jumpstart.

SCAMPER helps UX designers innovate by applying seven thinking techniques: Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, and Reverse. Each prompts you to look at existing ideas or features differently. For example, you might ask: “What can we eliminate to simplify the user flow?” or “Can we adapt a feature from another product?”

SCAMPER encourages out-of-the-box thinking and reveals unexpected solutions. It works best once you’ve defined the user problem and want to explore enhancements or alternatives. You can apply it individually or as a team, on paper or with digital tools. Many UX professionals use SCAMPER during redesigns or when refining prototypes. Its structured prompts drive ideation beyond surface-level ideas, helping create user experiences that feel both novel and useful.

Discover the power of the SCAMPER technique to access new angles and precious design and user insights.

Choose your ideation method based on the project’s stage, your goals, and your team dynamics. For early-stage, divergent thinking, use brainstorming or Crazy 8s (sketching 8 ideas on 8 panels of a folded sheet of paper in 8 minutes) to generate lots of ideas quickly. If you’re refining concepts, SCAMPER or mind mapping can push your thinking deeper. When working with a team, collaborative methods like storyboarding, role-playing, or brainwriting ensure everyone contributes. For solo work, sketching and journaling work well.

Consider constraints, too: short timelines favor quick methods like rapid sketching, while complex problems might benefit from scenario-based ideation. Match the method to the type of insight you want: emotional, functional, or behavioral. Test different techniques over time to find what consistently delivers strong, user-centered solutions. Picking intentionally helps maximize creativity and align ideas with your design goals.

Explore mind maps to find how to use this powerful ideation tool to access vital insights towards the best designs.

To overcome creative blocks, shift your perspective and reduce pressure. To start, revisit your user research: it often sparks fresh ideas. Change your environment or switch mediums; for example, move from typing to sketching. Use prompts like “What would a child do?” or “How would this work in a different industry?”

SCAMPER or role-playing can also unlock new angles. Take a short break or walk: stepping away often clears mental clutter. If you’re working in a group, introduce timed exercises like Crazy 8s to reignite momentum. Most importantly, let go of perfection and judgment, as creative flow thrives in safe, playful spaces. Encourage quantity over quality at first. Once the ideas flow again, refine and cluster them. Creative blocks happen to everyone; it’s normal and natural, so use them as a signal to try a new approach.

Explore the nature of creative blocks to understand how to handle them best, for yourself and the benefit of the design solutions you can unlock.

After ideation, evaluate ideas based on criteria like user value, feasibility, and alignment with business goals. Group similar ideas and look for themes. Use tools like an impact-effort matrix to map ideas; prioritize those with high impact and low effort. Dot voting works well in teams to highlight popular concepts.

Consider user research insights, too: Which ideas solve real pain points? Prototyping a few top concepts can help validate them through quick user feedback. Avoid favoring flashy ideas without substance. Instead, focus on solutions that balance creativity with practicality. Document why certain ideas were chosen to keep decision-making transparent. This structured evaluation process ensures your final concept serves users and stakeholders while it stays well-grounded in the project’s objectives.

Understand more about user research to unlock a treasure trove of insights you can apply to help find the best design ideas for your user problems.

Yes, combining ideas often leads to stronger, more innovative UX solutions. During ideation, you’ll likely generate ideas that tackle different angles of the same problem. So, look for ways to merge complementary concepts: for instance, pairing a simplified navigation with a personalized dashboard.

Use clustering or affinity mapping to group ideas, then explore how they might integrate. Combining ideas helps create well-rounded solutions that address multiple user needs. Just make sure the final concept stays cohesive and user-centered. Avoid feature bloat; prioritize simplicity and usability. Prototyping helps test if the combination works in practice. Many successful products evolved from blended concepts. Merging ideas unlocks richer experiences, so don’t be afraid to mix, match, and iterate until the solution truly resonates with users.

Explore another ideation technique, embrace opposites, to learn another helpful way you might combine with a method you’ve already tried.

Stop ideating when you’ve met your goals: generated diverse options, identified high-potential ideas, and aligned on a clear direction. If your top ideas consistently solve the user problem and meet project constraints, it’s time to prototype. Use decision-making tools like dot voting or impact-effort grids to confirm team alignment.

Revisit your problem statement; have your ideas addressed it well? If new ideas start repeating or feel forced, it’s a sign the session has run its course. Consider deadlines, too; ideation is vital, but it’s one phase in the UX process. Move forward to test and refine your top concepts. UX design thrives on iteration, so you’ll revisit ideas as you need to. Progress matters more than perfection, and transitioning from ideation to action keeps your design process user-focused and efficient.

Peer into the practice of prototyping to explore the many powerful avenues it opens for the right design ideas.

Common ideation problems include unclear goals, lack of user insights, and fear of judgment.

Without a clear problem statement, teams generate irrelevant ideas. Skipping user research leads to solutions that miss real needs. In group settings, dominant voices can overshadow quieter participants, reducing diversity of thought.

Creative blocks and groupthink limit innovation, too. Plus, poor facilitation or unstructured sessions often waste time.

To avoid these pitfalls, start with solid research, craft clear “How Might We” questions, and foster an inclusive, playful atmosphere. Use time-boxed methods to stay focused and energize the team. Document everything to track progress. The best UX ideation combines structure with creativity, grounding bold ideas in real user problems.

Explore how to get away from groupthink so you can help steer a better course for your design projects and the solutions that emerge for users to enjoy.

Hay, L., Duffy, A. H. B., Gilbert, S. J., Lyall, L., Campbell, G., Coyle, D., & Grealy, M. A. (2019). The neural correlates of ideation in product design engineering practitioners. Design Science, 5, e29.

This study is one of the first to explore the neural basis of ideation in practicing professional product design engineers using fMRI. It compared brain activity during ideation versus control tasks and found greater activation in the left cingulate gyrus and potential involvement of the right superior temporal gyrus. Notably, no significant differences were found between open-ended and constrained ideation tasks. This research is important because it shifts the understanding of creative design thinking from abstract theory into cognitive neuroscience, providing empirical insight into how ideation unfolds in the professional design mind: relevant for improving UX and design workflows.

Hu, W. L., & Reid, T. (2018). The effects of designers’ contextual experience on the ideation process and design outcomes. Journal of Mechanical Design, 140(10), 101101.

This experimental study examined how contextual experience influences creative ideation in design. Using EEG measurements and evaluation of ideation outcomes (novelty, quality, quantity) from 33 participants, the authors found that greater familiarity with the design context negatively affected creativity, particularly novelty. This counterintuitive finding suggests that prior experience may constrain ideation by reinforcing habitual thinking patterns. For UX design practitioners and teams, the implications are clear: incorporating fresh perspectives and non-experts into the ideation process may lead to more innovative outcomes by offsetting the potential cognitive rigidity of experts.

Campbell, G., Hay, L., Gilbert, S. J., McTeague, C., Coyle, D., & Grealy, M. A. (2024).

Functional activity and connectivity during ideation in professional product design engineers. Design Studies, 91–92, 101247.

This recent fMRI study extends prior research by focusing on brain network connectivity during ideation in professional designers. Unlike studies that isolate brain regions, this research explores how multiple networks, including executive control, salience, default mode, and visual systems, interact dynamically during creative thinking. The findings emphasize that ideation is a distributed, multimodal process involving switching between cognitive control and imagination. For UX and product designers, this underscores the value of supporting diverse modes of thinking during ideation, from visualization and sketching to reflective assessment. It strengthens the cognitive foundation of design thinking by detailing how the brain organizes idea generation.

Kelley, T., & Kelley, D. (2013). Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within Us All. Crown Business.

This book, from two leading voices in design and innovation (of IDEO and the Stanford d.school), argues that creativity and ideation are not reserved for “creative types” alone but can be nurtured and embedded in everyday work. The authors draw on rich stories and case‑studies to show how teams can generate and build on ideas, overcome fear of failure, and create a culture of ideation. Because ideation underpins innovation in UX design (the “how might we…” stage of design thinking), this book is influential in shifting mindset and practice toward more generative, idea‑rich workflows.

Buxton, B. (2007). Sketching User Experiences: Getting the Design Right and The Right Design. Morgan Kaufmann (Elsevier).

Bill Buxton’s book importantly foregrounds ideation via sketching: that is, not only generating ideas, but making them visible early, exploring many design alternatives, and choosing the “right design” (not just “designing right”). The book links ideation, sketching, prototyping and iteration, thereby helping UX designers transition from vague ideas to concrete concepts. It’s highly respected for placing ideation at the center of the UX process and for giving practical and philosophical justification for early divergence in design work.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Ideation by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Ideation with our course Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your experts for this course:

Don Norman: Father of User Experience (UX) Design, author of the legendary book “The Design of Everyday Things,” and co-founder of the Nielsen Norman Group.

Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

Mike Rohde: Experience and Interface Designer, author of the bestselling “The Sketchnote Handbook.”

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!