Let’s examine some concepts that involve our users’ worlds. Both concepts inhabit the same scale; understanding them, you’ll be able to appreciate your users far better.

Assembling

IKEA is a heavyweight multinational that needs little introduction. Founded in 1943 in Sweden, by early 2008 it had become the world’s largest furniture retailer. IKEA’s distinguishing signatures are “ready-to-assemble” and “flat-packed”. From lamps, to beds, desks, to sofas, even houses, IKEA has indelibly imprinted its brand in the popular psyche.

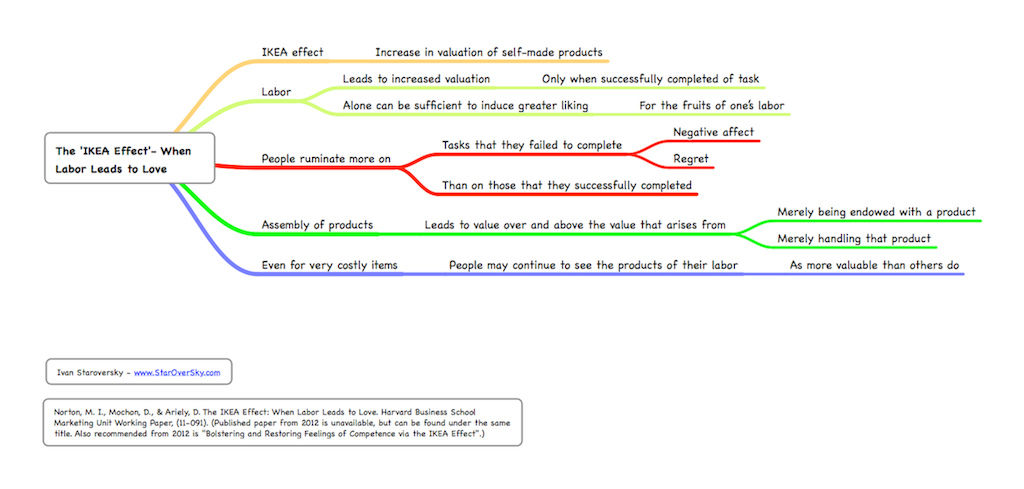

Author/Copyright holder: staroversky . Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC 2.0 .

Have you noticed that every product has a name there, such as “Klippan” or “Ludvig”? Have you ever found yourself going there with family/friends for a day out, even if you didn’t need a new bookcase? Was it for lunch, and some window shopping (even if there are few windows in a given IKEA superstore?). Third, did you realize that when you’re inside an IKEA store, you cannot tell the difference between one here and one there? Lastly, did you ever find yourself loving that bookcase you didn’t think you were going to buy so much that you bought it, anyway?

Let’s hold onto that idea. Fellow designers, we have just come across the IKEA effect. The IKEA effect is a recent phenomenon. It even has a Wikipedia entry, wherein it has been defined as a “cognitive bias in which consumers place a disproportionately high value on products they partially created.” That means that someone can deviate from how he/she would normally rationalize or make a judgment to the point that he/she can create his/her own subjective reality around that object. In other words, if, for example, Gary were to go to another furniture store and see a pine-slatted bookcase already assembled, and then go to IKEA, he’d come out with the similar-looking IKEA bookcase but not the same feeling of self-accomplishment. Even if Gary just has to follow a set of – sometimes pretty complicated – step-by-step instructions, the point is that he achieves the IKEA effect because he made the bookcase. Thus, making it much more valuable for him.

This phenomenon drew the attention of three authors - Michael I. Norton, Daniel Mochon, and Dan Ariely - in 2011. These authors titled their article “The IKEA Effect: When Labor Leads to Love” because the framework for their research was to find out about the value participants attached to their own labor. Their abstract declares their study’s relevance, homing in on one particularly fundamental observation. Norton, Mochon, and Ariely noted that the IKEA effect is as true for consumers who profess an interest in ‘do-it-yourself’ projects as for those who are relatively uninterested. Their paper reflects on how assembling IKEA products connects with people’s sense of well-being and feelings of productivity. Even if they might find the task unlikeable, people still rate this work as rewarding.

Returning to Gary in his lounge, we can still find him admiring his bookcase with its glinting, shiny screw-heads. Imagine, if as designers, we could replicate that effect in every design we composed, we would really satisfy our users’ needs at different levels. If you’re familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, then this must ring a bell. However, let’s see it from a different approach.

People Need to Feel Creative — Let’s Get Convivial!

The IKEA effect captures the essence of how sometimes users prefer to commune with the designs of others by “completing” them in the comfort of their own home than passively bring home completed goods. “Product becomes project” might sum it up well. However, we can also consider this effect in the light of another piece of scholarship.

Liz Sanders, the founder of MakeTools and author of Convivial Toolbox, writes in her article “Scaffolds for building everyday creativity” (2006) of the growing need of everyday people to achieve more creative ways of living.

Although you may argue about the creativity involved in assembling IKEA furniture, their products do fall into the category of “convivial tools”. This term was coined by Ivan Illich – a radical theorist of the 1960s and author of the book Tools For Conviviality –; who considered that there are two basic types of tools:

“Convivial tools allow users to invest the world with their meaning, to enrich the environment with the fruits of their visions, and to use them for the accomplishment of a purpose they have chosen. Industrial tools deny this possibility to those who use them and they allow their designers to determine the meaning and expectations of others.”

According to Illich, people have both a consumptive and creative mindset, and this leads to a need for a balance between consumptive and creative activities. Sanders confirms Illich’s predictions, noting that the balance was heavily stacked in the favor of industrial tools, while convivial tools represented about a tenth of their volume. Sanders predicted that “tomorrow’s” balance would be just that – a true balance between the industrial tools and convivial tools, or, respectively, the consumptive mindset and the creative mindset.

The 4 levels of consumption

These include all the things that you’d expect from a typical shopping experience. Sanders identifies them as shopping, buying, owning, and using.

The 4 levels of creativity

According to Sanders, there are at least four levels of creativity that everyday people seek.

Level of creativity | Motivations | Requirements |

Doing | To get something done/ to be productive | Minimal interest Minimal domain experience |

Adapting | To make something on my own | Some interest Some domain expertise |

Making | To make something with my own hands | Genuine interest Domain experience |

Creating | To express my creativity | Passion Domain expertise |

Before we move on, do you see how having these levels in mind can help you in your design practice? Whenever you’re considering different approaches for user experience, you can recall these levels and think about which of your end-user’s levels of creativity you’re targeting.

Going back to our IKEA effect: How does the IKEA assembling fit within these levels?

The IKEA effect authors demonstrated the magnitude of this effect: consumers believe that their self-made products rival those of experts. The curious thing is that this effect is not a product of adapting, making or creating. It is just the result of doing. If we take a quick look back at the levels of consumption, we see straightaway that the IKEA effect has something else — investing the user in the creation of new furniture.

Author/Copyright holder: Unknown. Copyright terms and licence: Unknown.

The motivation behind the doing is to accomplish something through productive activity. Doing requires a minimal amount of interest and the skill requirements are low as well. For Sanders, the doing level is just consuming readymade products. However, for the IKEA effect authors, the results from their research show that a successful assembly of products leads to value over and above the value that arises from merely being endowed with a product, or merely handling that product. There is only one requirement: successful completion is an essential component for the link between labor and liking to emerge.

Therefore, the IKEA effect might just be a new level of consumption from which, as designers, we can also learn. Take the personalization options on a website or app, we know that users value this option but very few use them. In the light of the IKEA effect, users might just be happier picking from a ready-made template and changing the background.

How We Can Design for “Convivial Tools Users”

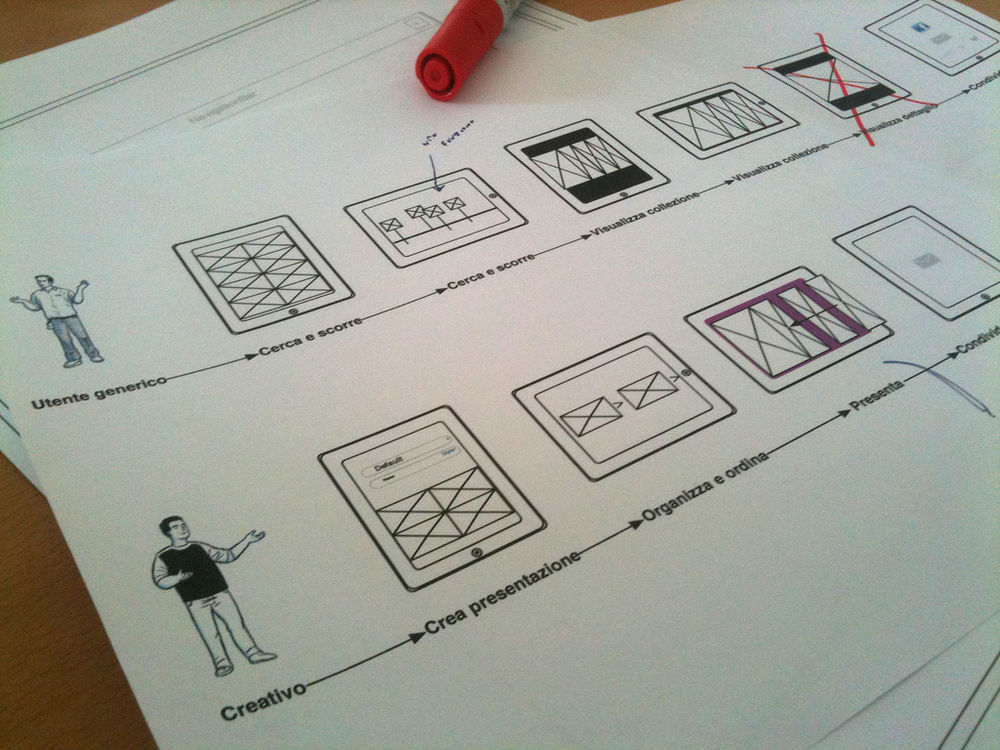

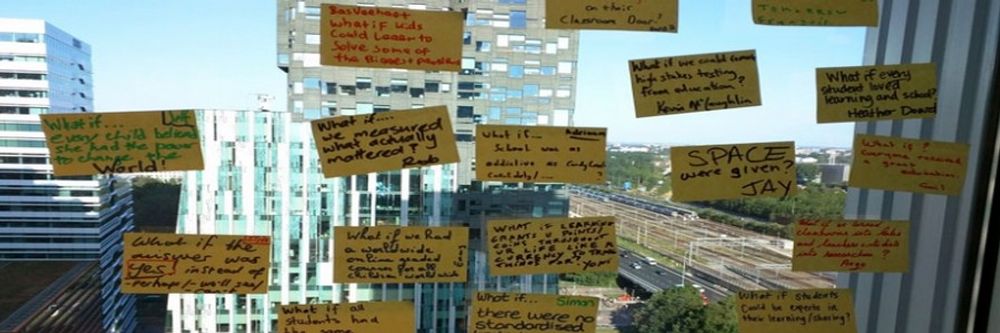

We can build scaffolds for our users’ experience. This is typically done in co-creation sessions. Applying this method leads to a special type of communicational space that enables, supports and allows for creative behavior. Here, we must ask ourselves questions such as what is too much to put into a design, i.e., what would suppress the user’s creativity rather than help it. How much free rein can we give the user and how much of our own designer’s creativity should feature in the design?

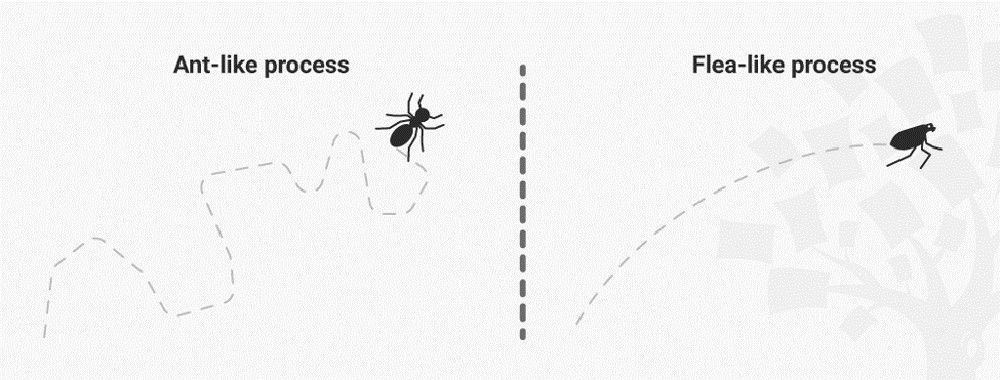

We can work with our users in the experimental phases of our design; we can co-create with them. We are moving away from the traditional design process and into new design spaces. As designers, we can see that we can engineer the creativity of other people in our designs by handing some control over to them.

During a co-creation session, for example, we would give users a toolkit to create a collage of their world. From examining this, we can shape our designs to fit them where they will use our designs. In other words, our scaffolding has come to them, touched their world, and so we can take away priceless data to build their UXs for them. Co-creation is very close to participatory design; we work together with the end users to come up with the design solutions.

Centermost to designing in this new way is understanding “everyday people”. Once, companies designed with oversimplification in mind. Market research was cruder many years ago. If a firm rolled out a design, it would see how it did later. That basically presumed that everyday people were just consumers, not users.

Interestingly, Sanders notes that everyday people “should drive the design process to the extent that they are capable and willing. If they are at a high level of creativity in a domain, then they should drive the design process. If they are at a low level of creativity, on the other hand, they will probably be content to consume what we deliver.” We just need to be aware of the fact that a user is not at the same level of creativity for everything and at all times. Thus, we need to cater for these different levels. These will depend on users’ interest in that specific product, the particular moment in their lives, their contexts, etc. If I just bought a new house, I’ll probably be in a creative mode to decorate it and make it my own. If I just moved temporarily into a rented house, I will probably opt for a functional approach: just consume as it is delivered.

The Take Away

In 2011, authors of a Harvard Business School article identified “the IKEA effect”, arguing and proving that users invest more interest in designs that they get to interact with, in this case, by assembling, even if assembling furniture is not their hobby. People have an innate need to feel productive; they are rewarded when they build an IKEA item, feeling accomplishment and satisfaction of a creative drive.

Creativity in user experience is nothing new. Ivan Illich, a radical 1960s theorist, identified two basic types of tools: convivial tools, which allow users to apply creativity to their world, and industrial tools, which deny this ability and allow the designers of goods free reign to dictate what users should expect.

According to Illich, people have both a consumptive and creative mindset, with the former matching the old industrial tools mindset, while the creative mindset remains relatively tiny. The IKEA effect is an example of a convivial tool, although at a less sophisticated and creativity level; except for IKEA hackers, of course..

In 2006, Liz Sanders, the founder of MakeTools, LLC, built on Illich’s viewpoint with a nonetheless groundbreaking observation that people (users, designers, everyone) need to feel creative. Everyday people are feeling more of a need to get creative in how they interact with and inhabit their worlds. Sanders states that new design spaces are evolving to assist people there, and that one day there will be as many convivial tools as industrial tools. Designers have to meet users using scaffolding; creating a specific communicational space that enables, supports, and allows for creative user behavior.

Users are no longer the faceless consumers of products that companies rolled out regardless. They are experts in their own worlds. Some, because of past experiences, prefer things that others don’t. Listen to them all.

Where to Learn More:

Norton, M. ,Mochon, D. Ariely, D. (2011). “The ‘IKEA Effect’: When Labor Leads to Love.” Harvard Business School (dissertation).

Sanders, E.B. (2006).“Scaffolds For Building Everyday Creativity”. Design for Effective Communications: Creating Contexts for Clarity and Meaning.

Vedantam, S. (2013). “Why You Love That Ikea Table, Even If It’s Crooked”. Hidden Brain.

Carter, T.J. (2012). “The IKEA Effect: Why We Cherish Things We Build”. Psychology Today.

References

Hero Image: Author/Copyright holder: rarye. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY 2.0