Understanding Early Adopters and Customer Adoption Patterns

- 1.1k shares

- 4 years ago

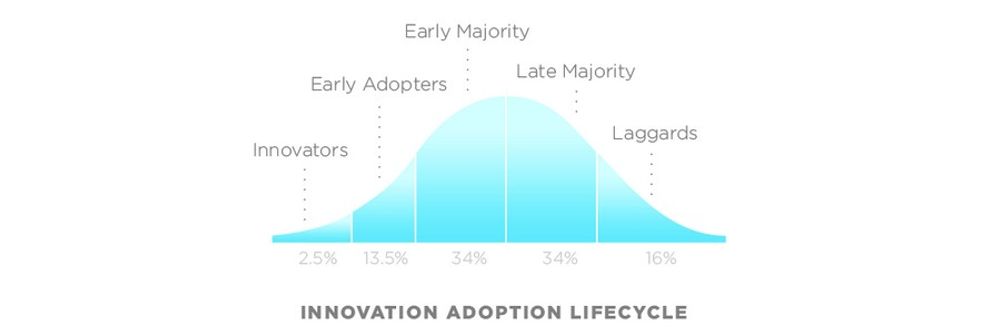

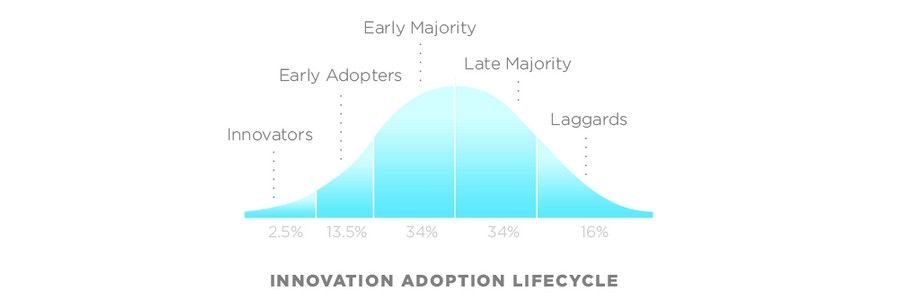

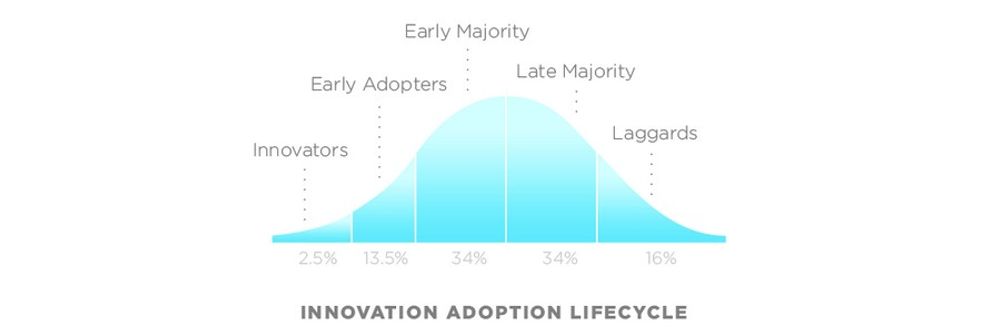

Consumers are divided into 5 adopter categories based on their behavioral patterns and values. The 5 adopter categories, in order of their speed of uptake, are:

1. Innovators

3. Early Majority

4. Late Majority

5. Laggards

When a new product first emerges in the market, it must be accepted by the different adopters that make up the market.

Identifying adopters is valuable for crafting marketing messages. By addressing any adopter category’s values, maximum impact is more likely.

The adoption curve for new products illustrates the sequence in which different categories of consumers adopt innovations. It typically consists of five stages: Innovators, Early Adopters, Early Majority, Late Majority, and Laggards.

These groups adopt products at different times, influenced by their willingness to try new things, social status, and other factors. The curve provides insights into market penetration and the potential growth of new products. For a deeper dive into this topic, including how early adopters influence customer adoption patterns, read the article 'Understanding Early Adopters and Customer Adoption Patterns' on the Interaction Design Foundation.

Consumer adoption of a new product refers to the process by which an individual or group uses an innovation. It's typically depicted by a curve that breaks consumers into five categories: Innovators, Early Adopters, Early Majority, Late Majority, and Laggards. Each category represents a specific segment's willingness and timeframe to adopt new products. Factors like perceived benefits, risks, and social influence can impact the speed of adoption. For comprehensive insights into how consumers transition through these stages and the influence of early adopters, explore the article 'Understanding Early Adopters and Customer Adoption Patterns' on the Interaction Design Foundation.

Laggards represent the final group on the adoption curve for new products. Unlike earlier segments, they're typically skeptical of change and innovations. Laggards often wait until a product has been established in the market and, even then, might resist adopting it. In the video discussion about product improvements and design changes, there's an emphasis on understanding user behaviors and the reasons behind their actions. While innovations might cater to early adopters and the majority, it's essential to recognize the hesitancy of laggards. Dive deeper into this topic by watching the video discussion on the Interaction Design Foundation.

No, early adopters are typically not risk-averse. They're risk tolerant. Early adopters are individuals who eagerly embrace innovations before the majority of the population. They're willing to take risks by trying out new products or technologies, even when there's limited information available. Their adventurous nature and willingness to experiment often place them ahead of the curve in adopting new solutions.

The five stages are:

Innovators - The first group to adopt a new product, open to risks and exploration.

Early Adopters - Enthusiastic about new ideas and willing to champion them.

Early Majority - More deliberate in adoption, influenced by feedback from early groups.

Late Majority - Skeptical about innovations, adopting only after the majority have tried them.

Laggards - Last to adopt, typically resistant to change.

Each stage represents a segment of consumers with distinct characteristics.

New product innovations can be categorized into two main types:

Incremental Improvements: These involve enhancing existing product features. Examples include refining user interfaces or adding features that customers expect. It's like allowing job seekers to search for jobs near them – a seemingly minor addition that can significantly impact user experience and metrics.

Disruptive Innovations: These radical changes create new markets or reshape existing ones. It might involve reimagining how a product functions. For instance, allowing job applicants to use video resumes instead of traditional text or pivoting into training and certifications to meet user needs.

To truly understand user needs and drive innovation, in-depth research and agile, quick usability testing are essential.

Let's talk about the difference between big, innovative changes to our product and small, incremental improvements, and the kinds of research that you might need in order to make these changes. We'll start with the incremental improvements because that's really the most frequent kinds of changes that we make as designers and researchers. While we all like to talk about designing things from scratch or making huge, sweeping changes,

the vast majority of people spend a lot of their time working on existing products and making them a little bit better every day. So, imagine you're building your new job marketplace to connect job seekers with potential employers. The product works. It's out in the real world being used by folks to find jobs every day. It's great! You made a thing that people are using, for money. Now, your product manager is looking at the metrics and they notice that a bunch of people are signing up and looking at jobs but they're not applying for anything.

Your job is to figure out why. So, what do you do? You can go ahead and pause the video and think about it for a minute if you want. There are a lot of different options you could go with here, but at the very least you're going to want to figure out the following things: Where are people stopping in the process and why are they stopping there? You'll probably want to dig into metrics a bit and figure out if folks do anything besides just look at jobs. Do they fill out their profile? Do they look at job details? Do they click the Apply button? And then do they give up at that point? Or do they never actually even get to that point?

Once you know where they're giving up, you'll probably do some simple observational testing of actual users to see what's happening when they do drop out. You'll probably also want to talk to them about why they're not applying. Maybe you'll find out that they get frustrated because they can't find jobs in their area. Well, that'd be great because that's really easy to fix; if that's the problem, maybe you can try letting them search for jobs near them. That's an *incremental change*. Now, what do we mean by that? It doesn't necessarily mean that it doesn't have a big impact on metrics.

Things like this can be hugely important for your metrics. If you manage to get lots more qualified candidates to apply to jobs, that's a huge win for the employers who are looking for great employees and it doesn't matter that it was just a simple button that you added. But it's not a wildly innovative change. In fact, it's a pretty standard feature on most job boards, and it's a very small improvement in terms of engineering effort, or at least it should be. If it isn't, there may be something wrong with your engineering department... which is a totally different course.

This change is *improving an existing flow*, rather than completely changing how something is done or adding a brand-new feature. OK, now, imagine that you're doing some observational research with your job applicants and you learn that for whatever reason they really don't have very much access to computers or they're not used to typing on a keyboard. This might lead to a very different sort of change than just searching for jobs in their area. Rather than making a small, incremental improvement to a search page, you might have to come up with an entirely different way for candidates to apply for jobs.

Maybe they need to film themselves using their phone cameras. This is a much larger change; it's *less incremental* since you're probably going to have to change or at least add a major feature to the entire job application process. You'll probably have to change how job seekers get reviewed by potential employers as well since they'll be reviewing videos rather than text resumes – which they might not be used to. This is a big change, but it's still incremental because it's not really changing what the product does.

It's just finding a new way to do the thing that it already did. OK, now, let's say that you have the option to do some really deep ethnographic research with some of your potential job applicants. You run some contextual inquiry sessions with them or maybe you run a diary study to understand all of the different jobs that they look at and learn why they are or aren't applying. Maybe in these deeper, more open-ended research sessions, you start to learn that the reason that a lot of potential job applicants drop out is because they just don't have the skills for the necessary jobs.

But what could *you* do about that? Well... our only options are either to find different applicants, find more suitable jobs or create some way to train our users in the skills that they need for the kinds of jobs that are available. All of those are really pretty big, risky ventures, but they just might be what we need to do to get more applicants into jobs. These are very big, and a couple of them are fairly innovative changes.

If the company pivots into, say, trainings and certifications or assessments, that definitely qualifies as innovation, at least for your product, but *how* does the research change for *finding* each of these sorts of things? Couldn't you have found out that applicants aren't qualified with the same types of research that you used to learn that they wanted to search by location? Maybe. Sometimes we find all sorts of things in very lightweight usability-type testing, but *more often* we find bigger, more disruptive things in deeper kinds of research – things like contextual inquiry, diary studies or longer-term relationships that we build with our customers.

Also, bigger, more disruptive changes often require us to do more in-depth research just to make sure that we're going in the right direction because the bigger it is the more risky it is. Let's say we ran some simple usability testing on the application process. That would mean we'd give applicants a task to perform, like find a job and apply to it. What might we learn from that? Well, that's the place where we'd learn if there were any bugs or confusing

parts of the system – basically, *can* somebody apply for a job? It takes more of a real conversation with a real user or a potential user to learn why they're not applying for jobs. It's not that one kind of testing is better than the other; it's that you can learn very different things with the different types of testing. Some types of research tend to deliver more in-depth learnings that can lead to big breakthrough changes, while other types of research tend to lead to smaller, more incremental but still quite useful and impactful changes. Both are extremely useful on agile teams, but you may find that the latter is more common just because many

agile teams don't really know how to schedule those big longer-term types of research studies, while running quick usability testing on existing software is quite easy and can even often be automated.

Dive deep into adopter categories and understand their implications on product design by enrolling in the Get Your Product Used: Adoption and Appropriation course on Interaction Design Foundation. This comprehensive course offers insights into user behavior, adoption strategies, and methods to ensure your product resonates with target audiences. Stay ahead by equipping yourself with essential knowledge. Visit Interaction Design Foundation for more expert-led courses on UX and product design topics.

Here's the entire UX literature on Adopter Categories for New Products by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Adopter Categories for New Products with our course Get Your Product Used: Adoption and Appropriation .

Designing for user experience and usability is not enough. If products are not used—and it doesn’t matter how good they are—they will be consigned to the trash can of history.

Sony’s Betamax, Coca-Cola’s New Coke, Pepsi’s Crystal Pepsi, and McDonald’s Arch Deluxe are among the most famous products which made it into production but failed to wow their audiences, according to Business Insider. In fact, Harvard Business Review dedicated a long piece to “Why most product launches fail”—so it’s not just big brands that aren’t getting their design process right but a lot of businesses and individuals, too.

So, what is the way forward? Well, once you’re sure that the user experience and usability of your product work the way you want them to, you’ve got to get your designs adopted by users (i.e., they have to start using them). Ideally, you want them to appropriate your designs, too; you want the users to start using your designs in ways you didn’t intend or foresee. How do we get our designs adopted and appropriated? We design for adoption and appropriation.

This course is presented by Alan Dix, a former professor at Lancaster University in the UK and a world-renowned authority in Human-Computer Interaction. Alan is also the author the university-level textbook “Human-Computer Interaction.” It is a short course designed to help you master the concepts and practice of designing for adoption and appropriation. It contains all the basics to get you started on this path and the practical tips to implement the ideas. Alan blends theory and practice to ensure you get to grips with these essential design processes.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!