External Cognition in Product Design: 3 Ways to Make Use of External Cognition in Product Design

- 734 shares

- 5 years ago

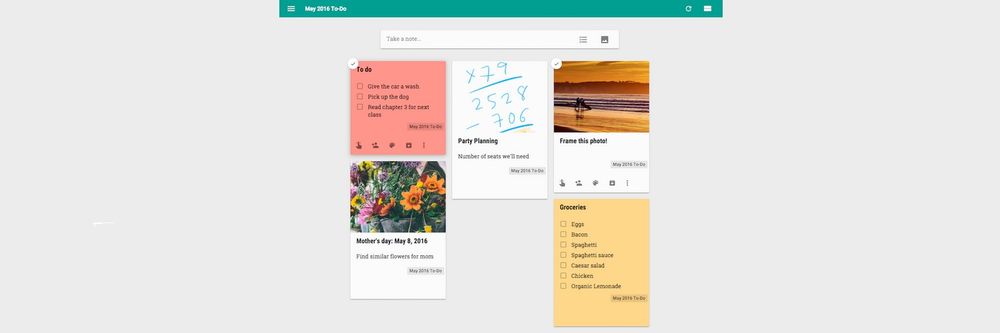

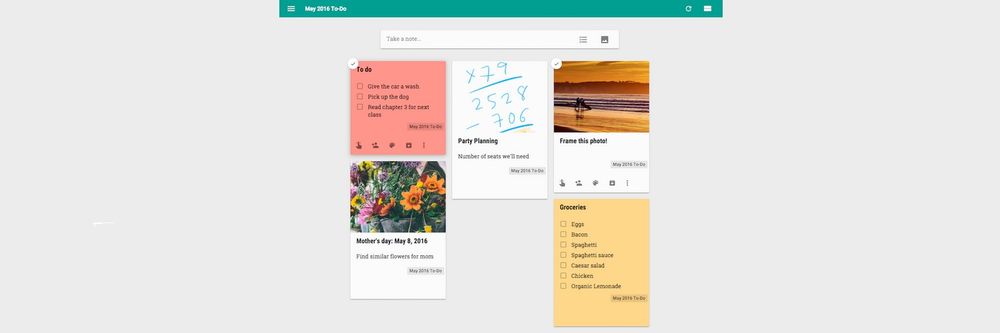

Cognitive tracing is a cognitive activity, that often goes hand-in-hand with annotation—or note-taking, whereby we rearrange or reprioritize items, tasks, or even our thoughts and actions into different orders or structures. We apply it when we adapt to changing circumstances, we want to optimize our current situation, or to support other types of cognitive processes like externalizing memory load, computational offloading, and annotating.

The primary goal of cognitive tracing is to minimize cognitive load. For example, cognitive tracing includes the simple action of crossing off a specific item from your weekly To-Do list after you’ve completed it, whether on paper, your smartphone, or your calendar. As you wrap up each task one by one, you keep track by crossing them out and reprioritizing the next one on the list. It’s a cognitive process dependent on ever-changing conditions.

In this video, Professor Alan Dix talks about the benefits of To-Do and Done lists and how they can help declutter the mind. He states, “...Very often you've sent an email to somebody and you're waiting for a reply… it's something… in your mind that needs to be done… Now, if there's a deadline, you need to probably at some point remind them… But before that point, there's nothing you can do about it, and yet it's still eating up your mental energy. Write it down—well, on paper… let the paper worry; let the computer system worry… But get it out. Don't let it clutter your head.” Important words to live by, and a perfect example of how cognitive tracing can be applied in your work life and beyond.

Since User Experience (UX) design is an iterative process, a designer should consistently trace and refine their designs based on changing circumstances. For example, we can use cognitive tracing to improve the user experience after:

User feedback and research.

Changing requirements from a client.

Updated priorities or deadlines for the product or service launch.

For example, imagine you’re a UX designer assigned to improve the user experience of a web page’s navigation system. You could apply cognitive tracing to the process of designing an intuitive website navigation system in the following ways:

You map out the initial navigation structure for the landing page, including the main menu and submenus. You consider the logic of the presented information and the expected user flow.

UX researchers gather user feedback and conduct usability testing—annotation, another cognitive process closely related to cognitive tracing, plays an important role in this step. Based on their user research, they identify areas where users get confused or struggle to find information.

In response to user feedback, you engage in cognitive tracing by reordering menu items and navigation links or grouping related content under different categories for a more intuitive experience.

You may need to go a few steps further with A/B testing, to ensure responsive design for all screen types, and to improve accessibility overall.

A Kanban Board is a perfect example of a tool UX designers use to support cognitive tracing. In the image, you see the post-it note move from the To-Do section to the In-Progress section signifying a change in priority as the imaginary project progresses. The action of moving this task based on changing project goals or expectations is cognitive tracing.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

In this instance, you used cognitive tracing to adapt and rearrange the website's navigation. You took the target audience’s needs and behaviors into account to improve your design. It's a process of continuous fine-tuning and enhancement to create the most user-friendly experience possible.

More broadly, cognitive tracing involves adapting to changing conditions or priorities. It helps people make informed decisions and stay organized in their day-to-day activities and beyond. It might seem like second nature, but there are some surprising instances where we use cognitive tracing.

The most common examples of cognitive tracing include:

Reordering cards in a card game based on suits, ascending order, color, etc., to make strategic decisions as a game progresses and tactics change. For instance, holding onto a wild, draw-4 card in Uno is cognitive tracing.

As is crossing off items from a grocery list that have already been added to the cart.

Shuffling your Q and Z tiles around on a Scrabble tray to try to play the highest-scoring word is another example.

Scheduling tasks based on changing priorities or time constraints to effectively plan your next activities—canceling an appointment with your personal trainer because you have to pick the kids up early from school is also cognitive tracing.

Using a Gantt chart in a project management tool to ensure you complete a work project on time, shifting tasks as new challenges arise.

In a game of Scrabble, you unconsciously put cognitive tracing to good use when you reorganize your letter tiles and prioritize letters that earn more points, like Q and Z, in an effort to create higher-scoring words to win the game. You do this to optimize your situation in the game which changes with every round and new letter you draw.

Image from @Pixabay via Pexels. Fair Use.

What are the benefits of cognitive tracing?

Beyond the obvious benefits of reducing cognitive load and improving memory and learning, let’s explore some of the other advantages cognitive tracing offers to better individual performance and well-being:

Improved Task Management: Cognitive tracing tools such as To-Do lists, project management software, and calendars help you organize and prioritize tasks. This leads to better task management, increased productivity, and a greater sense of accomplishment.

Reduced Stress and Anxiety: Rearranging tasks based on priority decreases the stress associated with remembering everything. This can lead to reduced anxiety, especially in high-pressure or time-sensitive situations.

Time Savings: Your time is valuable and every second counts. Cognitive tracing can save you time by allowing you to quickly retrieve information, instructions, or resources. This efficiency can leave you more time for other tasks and leisure.

Task Accountability: Externalizing responsibilities through various tools creates a sense of accountability. You can track progress, deadlines, and completed tasks, leading to a more organized and productive approach.

Flexibility and Adaptability: When you restructure your schedule, duties, or tasks for optimization, you allow for greater flexibility and can more easily adapt to changing circumstances.

These are just a few of the benefits, but undoubtedly, there are no cons to implementing cognitive tracing in your everyday life. It can only help you, and we highly encourage you to give it a try.

In this video, Alan Dix describes how humans interact with computers from perception to action. “We don’t just act as an output; we act in order to live our lives,” he says. Like a computer needs to process information, so do humans. What comes after perception or before action? Cognition—it fits into this input/output cycle and helps us accomplish the tasks we want to complete. And if you dig deeper, you’ll find cognition includes processes such as externalizing memory load, annotation, and cognitive tracing which directly support achieving those tasks.

Cognitive tracing is an important example of a human external cognitive activity often mentioned alongside the following:

Externalizing Memory Load: When you offload or store information outside your mind with tools or external aids like notes, calendars, or digital devices to help you remember and manage information, reducing the cognitive effort needed to remember everything. E.g., when you set phone reminders to keep track of tasks instead of relying solely on your memory.

Computational Offloading: When you transfer complex computer tasks to another device or system to make them easier and improve performance. E.g., when you work together with an assistant to complete tasks faster and better.

Annotation: When you add notes or highlights to a text or document to explain, mark, or remember important parts. E.g., when you jot down thoughts in the margins of a school book.

Concepts not only applied in UX design but in various aspects of our daily lives, these cognitive activities present an invaluable strategy to unburden ourselves from excessive cognitive load while simultaneously improving our thinking skills. Like a computer needs space to store important files, people also have to make room in their minds for important and urgent tasks.

Using various tools like calculators, pencils, Kanban or Scrum boards, To-Do lists, calendars, etc., we are able to apply these external cognitive activities in our daily lives. It empowers people to externalize certain aspects of cognition to make our thought processes more efficient and effective. Cognitive tracing is one way we maintain and strengthen our cognitive functions.

Organizing our day-to-day and sorting the most to least important tasks in real-time is a part of cognitive tracing. As our circumstances inevitably change we have to adapt our thoughts and actions to optimize our present situation. Often, it’s unconsciously done, but it’s a strategy which reduces our mental load.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

If you reorder or restructure important ideas, tasks, items, etc., you free up mental resources that can then be directed toward more intricate and creative problem-solving, critical thinking, and decision-making. Whether it's the need to reschedule a work meeting, strategize in a game of Scrabble against a logophile, or simply stay on top of daily responsibilities, we are continually engaging in the brain's built-in organizational process known as cognitive tracing.

Start learning more about cognition and its importance in our course HCI: The Foundations of UX Design with Alan Dix.

If you’re interested in learning more about UX Design, the Interaction Design Foundation’s online courses are a great place to begin.

Learn more about cognitive and perceptual psychology in UX design from Jeff Johnson in our Master Class, How to Design with the Mind in Mind.

Or learn to master strategy with Adam Thomas in Strategy Custody: How to Secure Your Strategy's Success. Strategy is complex, it’s not something that you create once and leave alone—you need to keep interacting with it.

Read External Cognition in Product Design: 3 Ways to Make Use of External Cognition in Product Design for an in-depth understanding of all external cognitive processes, including cognitive tracing.

Learn about cognitive tracing and UX design-related topics by reading the insightful material on TECHNOLOGY / CULTURE / DESIGN / EXPERIENCE.

You can learn more about cognitive tracing and annotation via Christopher Cooper’s blog post on External Cognition.

Cognitive skills are crucial for learning, problem-solving, and thinking. They're the mental processes which help us understand and work with information. These skills involve how we learn, remember, solve problems, and pay attention rather than what we know. They cover areas like perception, memory, decision-making, and language abilities.

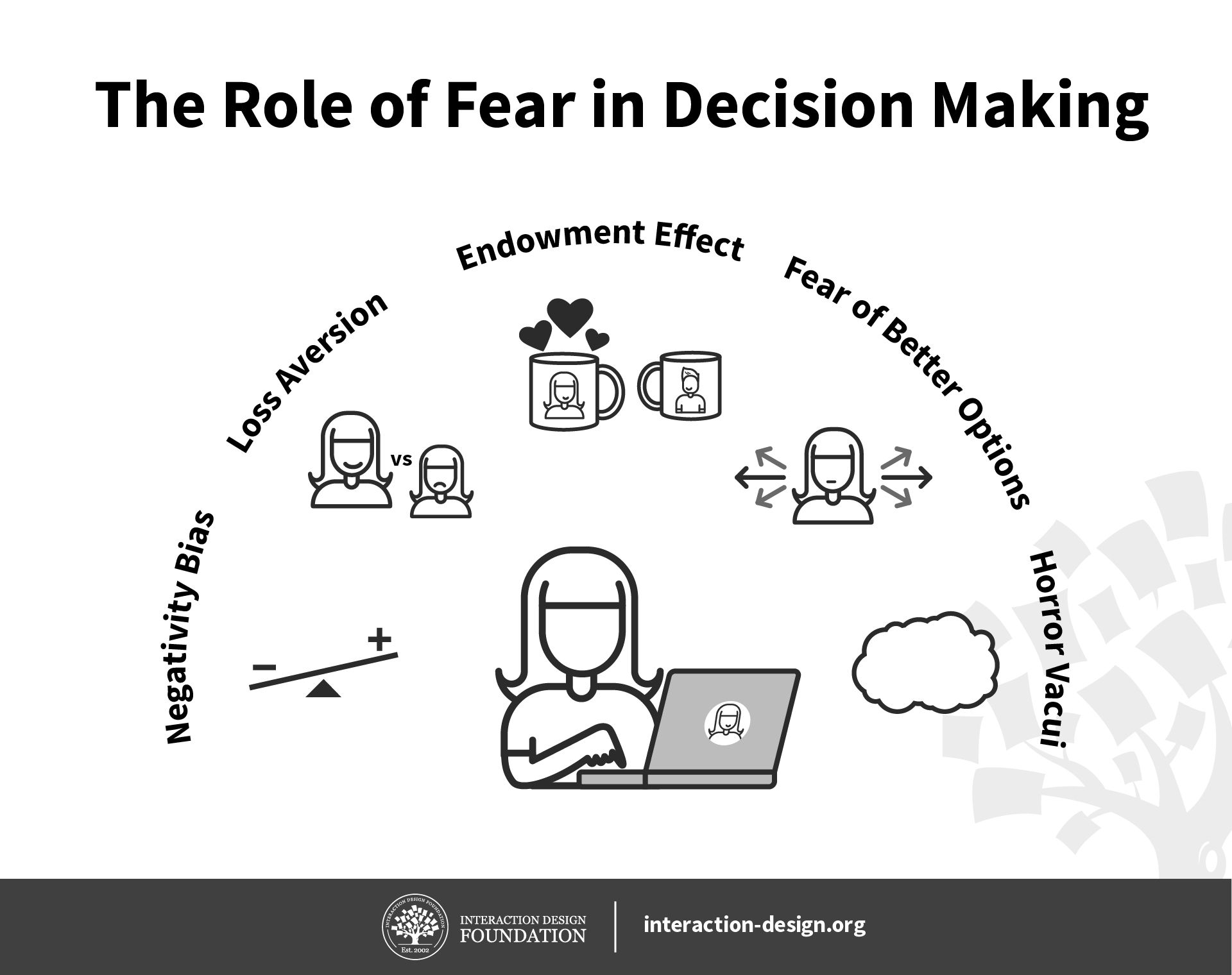

Fear is the brain’s warning system about forthcoming unpleasant experiences. We are hardwired to pick up negative signals and attach more weight to them than we would for gains we might enjoy. We’re afraid of missing out while also fearing better options. We’re afraid of losing our possessions and feel intimidated by emptiness. Indeed, some people may say they’re scared of “nothing”; “nothing” in this sense, though, can be mighty terrifying.

Fear is the brain’s warning system about forthcoming unpleasant experiences. We are hardwired to pick up negative signals and attach more weight to them than we would for gains we might enjoy. We’re afraid of missing out while also fearing better options. We’re afraid of losing our possessions and feel intimidated by emptiness. Indeed, some people may say they’re scared of “nothing”; “nothing” in this sense, though, can be mighty terrifying.

Christian Briggs, Daniel Skrok and The Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0

A cognitive test checks how well someone thinks and understands things; they look at skills like memory, paying attention, talking, and problem-solving.

These tests can help spot if someone has trouble thinking, called cognitive impairment.

The right test to take depends on the person. Some common ones are the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and the Clock Drawing Test.

Read about Understanding Cognitive Development: Approaches from Mind and Brain from Psychology Press, edited by Barbara Landau in 2013.

This book examines cognitive development from a multidisciplinary perspective, combining ideas from psychology, neuroscience, and cognitive science. It challenges traditional approaches that focus solely on either the child or the environment and advocates for a more integrated outlook. The book addresses three essential questions in the study of cognitive development as part of the movement toward a new, holistic framework. The book has been influential because it provides researchers, educators, and students with a comprehensive and up-to-date resource for understanding the complex processes involved in cognitive development.

Read Howard Gardner’s 2021 book, A Synthesizing Mind: A Memoir from the Creator of Multiple Intelligences Theory, from MIT Press.

This is a memoir by Howard Gardner, the creator of the multiple intelligences theory, which provides a deeper understanding of cognitive processes and intelligence. Gardner is famous for his groundbreaking work on multiple intelligences and argues the ability to combine information from various sources and perspectives is crucial in today's complex world. He also shares his own processes in the book. It has been influential for its contributions to understanding the importance of synthesis in cognitive development and its practical applications in various fields like HCI and beyond.

Some highly cited research on cognitive tracing, cognition, and related topics include:

González-Brenes, Juan P., and Jack Mostow. "Dynamic Cognitive Tracing: Towards Unified Discovery of Student and Cognitive Models." International Educational Data Mining Society 5 (2012).

Pu, Yiming, Weiping Wu, Tao Peng, et al. "Embedding cognitive framework with Self-Attention for Interpretable Knowledge Tracing." Scientific Reports 12 (2022): 17536.

Hasan, M. M. Eman. "Human-Computer Interaction (IS252) Chapter Three" Docplayer.net, 2019-20.

Zain Books. "Human-Computer Interaction: Lesson#6 Cognitive Frameworks." Accessed October 19, 2023.

External cognition is how your mind and the things you see and use work together. It's like when you use your phone to help you remember things or when you read a book to learn something new. External cognition explores how your thoughts and the outside world connect. You can learn more via our Topic Definition on External Cognition.

Cognitive and behavioral psychology are two parts of psychology which look at different aspects and use different methods. Here's how they're dissimilar:

Cognitive Psychology:

Looks at how people think, including memory, seeing, and solving problems.

Cares about what's going on in the mind.

Thinks learning is about gaining knowledge and processing information.

Studies things like memory and decision-making.

Believes learning is a change in what we know.

Says our minds are active when we learn.

“There’s a connection between feelings and decision making.” - Susan Weinschenk

Behavioral Psychology:

Focuses on what people do.

Looks at actions we can see and how the environment influences them.

Sees learning as something we do that can be seen and measured.

Studies how the environment and rewards or punishments shape behavior.

Thinks learning is a change in what we do.

Says everything we do is learned through the environment.

You can learn more about How to Design with the Mind in Mind with our expert Master Class speaker, Jeff Johnson.

Annotating means adding notes to a text, wireframe, video, etc., to explain, mark, or remember important parts. It's like using a highlighter to mark key information when studying.

Larry Marine suggests adding annotations to task analysis diagrams using a variety of colors that correspond to different flows. This technique helps him better visualize the user's journey and identify pain points or areas for improvement in the user experience.

Larry Marine suggests adding annotations to task analysis diagrams using a variety of colors that correspond to different flows. This technique helps him better visualize the user's journey and identify pain points or areas for improvement in the user experience.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

In UX design, designers frequently use post-it (sticky) notes for annotating and more!

Some popular annotation tools include the following:

Adobe Acrobat Pro DC: A widely used and feature-rich document annotation tool which offers a comprehensive set of annotation tools, including highlighting, underlining, and adding comments to text-based content.

Annotate: It makes working together on documents in real time easy. The interface is simple and provides plenty of tools for adding notes and making changes to text and images.

CVAT: It’s an open-source annotation tool; it allows users to annotate images and videos. It offers a range of annotation features, including bounding boxes, polygons, and keyframe detection.

Figma: A designer favorite; it offers a comprehensive set of features, including annotation tools. It allows users to add comments, highlights, and other annotations to various types of content. You can learn about the pros and cons of Figma in “The Top UX and UI Design Tools for 2023: A Comprehensive Guide”

Memory load is the amount of information an individual can hold in their working memory at any given time.

Do you ever make mistakes? Alan Dix talks about human error in the realm of design.

It can change depending on how complicated a task is and how much information you need to remember. When designing apps or websites, it's important not to make people remember too much because it can make tasks harder. Recognizing something is easier than remembering it.

It refers to transferring resource-intensive computational tasks from a device or our brain to a separate processor or external platform.

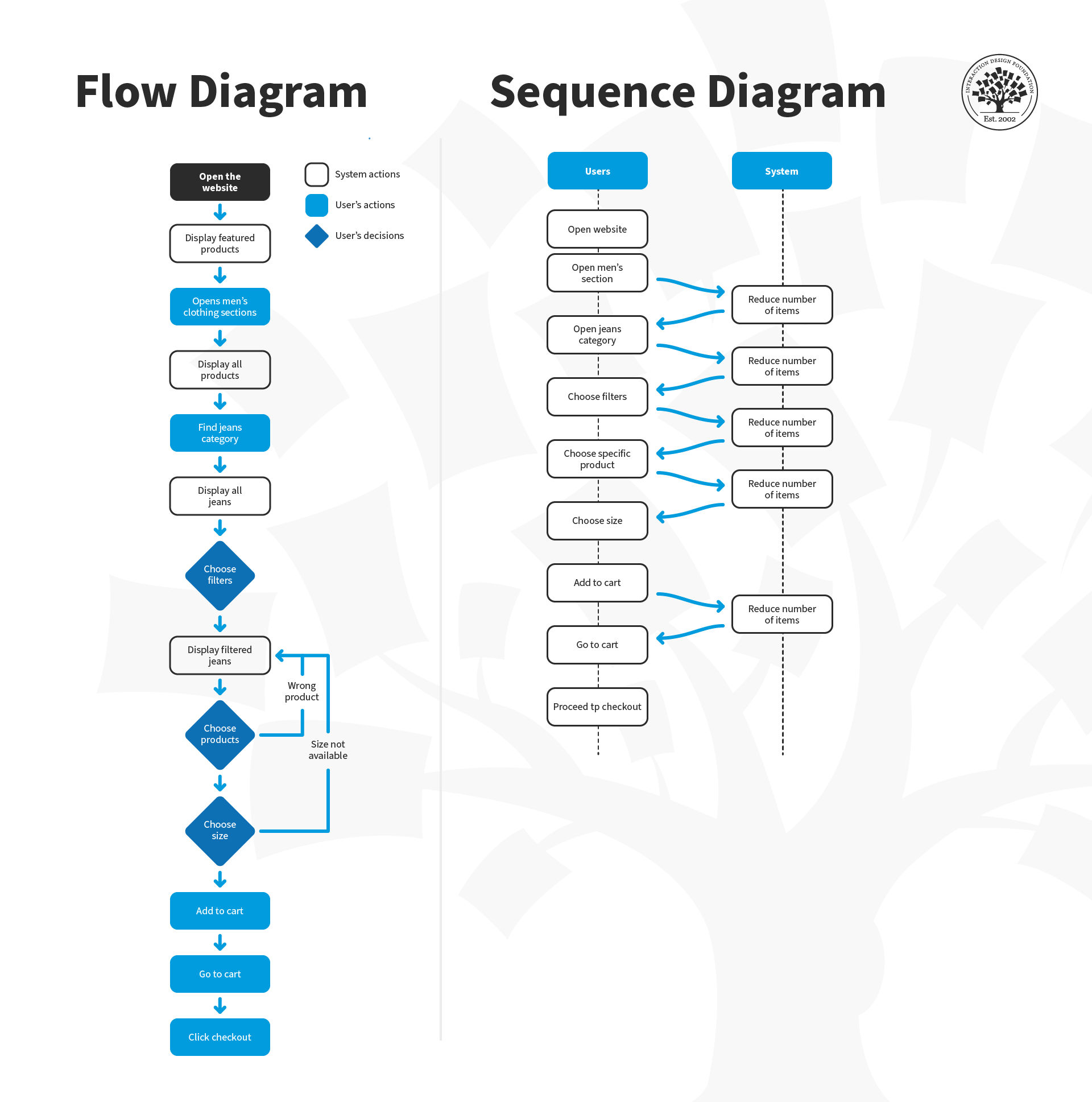

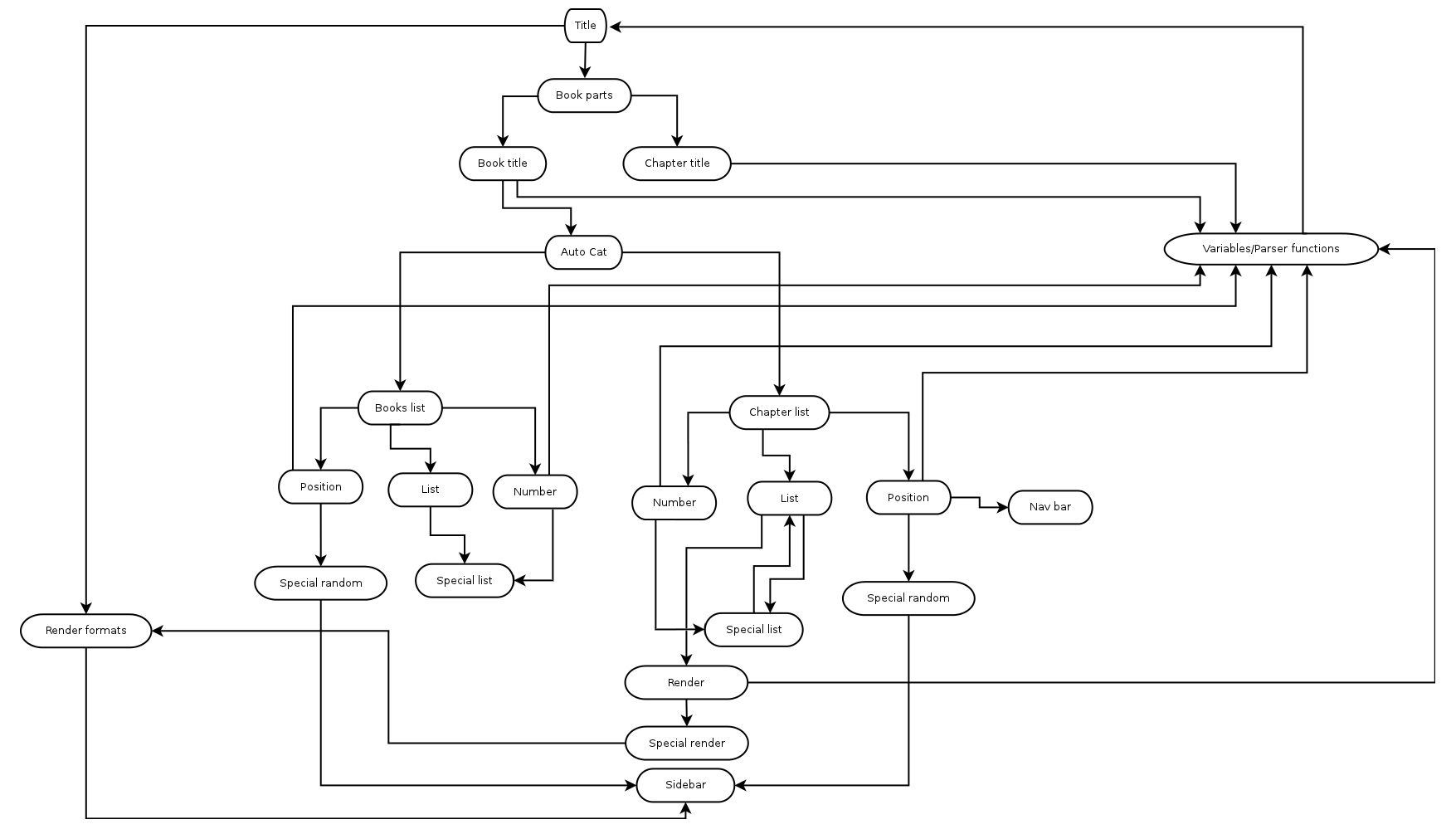

If the task is too complex to write in a list format – a diagram can be used instead.

If the task is too complex to write in a list format – a diagram can be used instead.

© Raylton P. Sousa, CC BY -SA 3.0

People use this technique to ease their mental load, even if it means letting a computer do part of the work, i.e., using a calculator to help solve for x.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Cognitive Tracing by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Cognitive Tracing with our course Human-Computer Interaction: The Foundations of UX Design .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your expert for this course:

Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!