Dressing Up Your UI with Colors That Fit

- 834 shares

- 4 years ago

Color theory is the study of how colors work together and how they affect our emotions and perceptions. It's like a toolbox for artists, designers, and creators to help them choose the right colors for their projects. Color theory enables you to pick colors that go well together and convey the right mood or message in your work.

“Color! What a deep and mysterious language, the language of dreams.”

— Paul Gauguin, Famous post-Impressionist painter

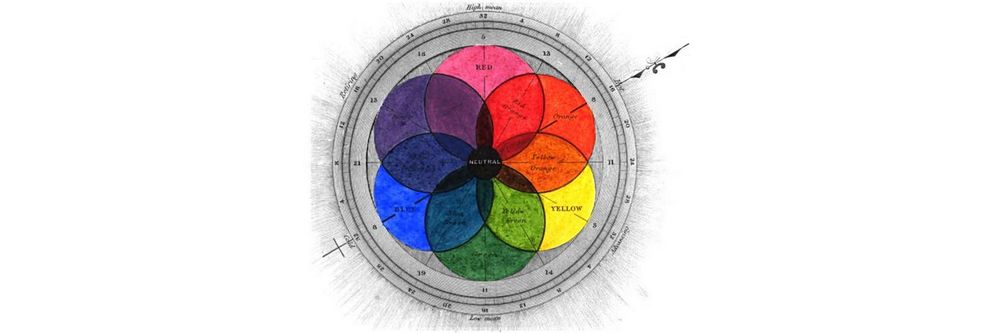

Sir Isaac Newton established color theory when he invented the color wheel in 1666. Newton understood colors as human perceptions—not absolute qualities—of wavelengths of light. By systematically categorizing colors, he defined three groups:

Primary (red, blue, yellow).

Secondary (mixes of primary colors).

Tertiary (or intermediate—mixes of primary and secondary colors).

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Hue is the attribute of color that distinguishes it as red, blue, green or any other specific color on the color wheel.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Value represents a color's relative lightness or darkness or grayscale and it’s crucial for creating contrast and depth in visual art.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Saturation, also known as chroma or intensity, refers to the purity and vividness of a color, ranging from fully saturated (vibrant) to desaturated (grayed).

In user experience (UX) design, you need a firm grasp of color theory to craft harmonious, meaningful designs for your users.

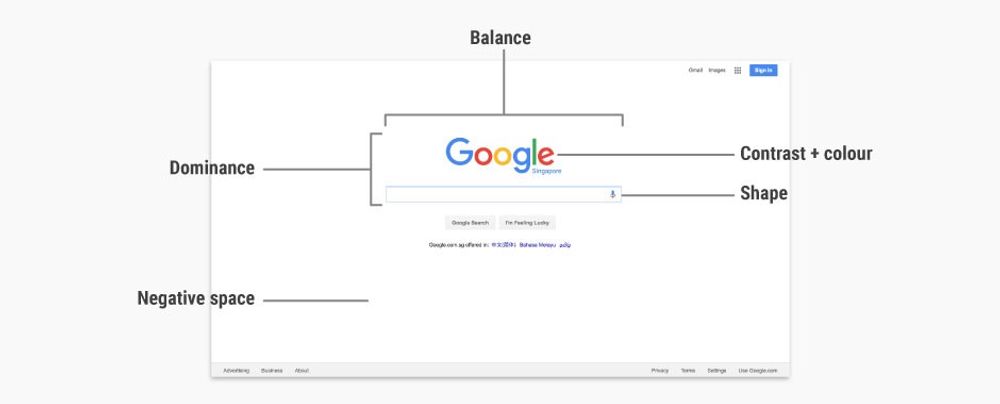

In screen design, designers use the additive color model, where red, green and blue are the primary colors. Just as you need to place images and other elements in visual design strategically, your color choices should optimize your users’ experience in attractive interfaces with high usability. When starting your design process, you can consider using any of these main color schemes:

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Monochromatic: Take one hue and create other elements from different shades and tints of it.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Analogous: Use three colors located beside one another on the color wheel (e.g., orange, yellow-orange and yellow to show sunlight). A variant is to mix white with these to form a “high-key” analogous color scheme (e.g., flames).

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Complementary: Use “opposite color” pairs—e.g., blue/yellow—to maximize contrast.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Split-Complementary (or Compound Harmony): Add colors from either side of your complementary color pair to soften the contrast.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Triadic: Take three equally distant colors on the color wheel (i.e., 120° apart: e.g., red/blue/yellow). These colors may not be vibrant, but the scheme can be as it maintains harmony and high contrast. It’s easier to make visually appealing designs with this scheme than with a complementary scheme.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Tetradic: Take four colors that are two sets of complementary pairs (e.g., orange/yellow/blue/violet) and choose one dominant color. This allows rich, interesting designs. However, watch the balance between warm and cool colors.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Square: A variant of tetradic; you find four colors evenly spaced on the color wheel (i.e., 90° apart). Unlike tetradic, square schemes can work well if you use all four colors evenly.

Your colors must reflect your design’s goal and the brand’s personality. You should also apply color theory to optimize a positive psychological impact on users. So, you should carefully determine how the color temperature (i.e., your use of warm, neutral and cool colors) reflects your message.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

For example, you can make a neutral color such as grey warm or cool depending on factors such as your organization’s character and the industry.

The right contrast is vital to catching users’ attention in the first place. The vibrancy you choose for your design is likewise crucial to provoking desired emotional responses from users. How they react to color choices depends on factors such as gender, experience, age and culture. In all cases, you should design for accessibility—e.g., regarding red-green color blindness. You can fine-tune color choices through UX research to resonate best with specific users. Your users will encounter your design with their expectations of what a design in a certain industry should look like. That’s why you must also design to meet your market’s expectations geographically. For example, blue, an industry standard for banking in the West, has positive associations in other cultures.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

However, some colors can evoke contradictory feelings from certain nationalities (e.g., red: good fortune in China, mourning in South Africa, danger/sexiness in the USA). Overall, you should use usability testing to confirm your color choices.

Take our course Visual Design: The Ultimate Guide.

Register for the How To Use Color Theory To Enhance Your Designs Master Class webinar with color experts Arielle Eckstut and Joann Eckstut.

See designer and author Cameron Chapman’s in-depth piece for insights, tips and examples of color theory at work.

For more on concepts associated with color theory and color scheme examples, read Tubik Studio’s guide.

As an artist, it's important to have a solid understanding of color theory. This framework allows you to explore how colors interact and can be combined to achieve specific effects or reactions. It involves studying hues, tints, tones, and shades, as well as the color wheel and classifications of primary, secondary, and tertiary colors.

The Color Wheel © Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Complementary and analogous colors are also important concepts to understand, as they can be used to create stunning color combinations. Additionally, color theory delves into the psychological effects of color, which can greatly impact the aesthetic and emotional impact of your art. By utilizing color theory, you can make informed decisions about color choices in your work and create art that truly resonates with your audience.

Color theory is a concept used in visual arts and design that explains how colors interact with each other and how they can be combined to create certain feelings, moods, and reactions. Arielle Eckstut, co-author of 'What Is Color? 50 Questions and Answers on the Science of Color,' explains that color does not exist outside of our perception, and different brains process visual information differently. Our retina, a part of the brain, plays a crucial role in color vision, and our brains constantly take in information from the outside world to inform us about our surroundings.

Watch this video for a deeper understanding of the science behind color:

Hi. My name is Arielle Eckstut, and I am the author of What Is Color? 50 Questions and Answers on the Science of Color. Color is an incredibly difficult subject, one that encompasses all kinds of categories of science and history and culture – you name it.

But today in about five minutes I'm going to try to answer this question: What is color? And I'm going to do that by starting with yet another question. In the fall, do the leaves change color if no one is there to see them? Take a moment to think about that: Do the leaves change color if no one is there to see them? Now, the *obvious answer* to this question is "Of course they change color

because the color of the leaves are inherent to the leaves themselves." But in fact, that is not true at all, and the answer is a resounding *no*. If there is not a living being with a brain observing those leaves, the leaves do not change color. And the reason for this is that there's no such thing as color without the *eyes* and the *brain*.

So, different brains process visual information differently. And I realized that this idea that color does not exist outside of our perception can be very difficult to swallow. And in fact, our brains go to great lengths to give us all of the colors that we see.

The source of our color vision is in our *retina*, a credit-card-thin sheet of neurons in the back of our eyeballs. And it's actually a part of our brain, our retina. It's the only part of our brain that exists outside of our skulls. And our retina is what we typically associate with sight in general. If I were to ask you, "Why do we have eyes?" most people would say, "So we can see."

But that was actually not the original purpose of our eyes and our retina. The original purpose was to tell us when to be awake and when to be asleep. So, our eyes sensed when it was light out and when it was dark out, and "when" is the most important word here because our eyes, our retinas have three different systems:

the *when system* being the most primitive and the first use of our eyes. The next system is the *where system*, and that tells us where we are situated in the world. Are we right at the edge of a cliff? Are we too close to a potential predator? Or are we too far to reach a berry that is ripe that we would like to eat?

Lastly, we get to our *what system* – the system that designers deal with on a daily basis but the one that is actually *least important* to our visual system. The what system is the system that we use when we are *focusing on something*, whether that be a computer screen or a phone or a face or a road sign. It's also the system that we use to see color.

Color scientist Mark Rea has a great quote that I adore: "Color is a pigment of our imagination." And that really is true. Our imagination plays such a big role when it comes to color. And our brains are constantly taking in information from the outside world to help inform us about what time of day it is, where we are in the world, what we're looking at,

which really gets us to the next question, which is: Why do we see color to begin with?

To learn color theory, enroll in the 'Visual Design: The Ultimate Guide' course on Interaction Design Foundation. This comprehensive course covers all aspects of visual design, including color theory. You will learn how colors interact with each other, how to combine them to create specific feelings and reactions, and how to use them effectively in your designs.

The course includes video lectures, articles, and interactive exercises that will help you master color theory and other key concepts of visual design. Start your journey to becoming a color theory expert by signing up for the course today!

Color theory helps us make sense of the world around us by providing a shorthand for using products, distinguishing objects, and interpreting information. For instance, colors can help us quickly identify pills in a bottle or different dosages.

Designers also consider cultural, personal, and biological influences on color perception to ensure the design communicates the right information. Ultimately, color helps us navigate the world safely, quickly, and with joy. Find out more about the significance of color in design by watching this video:

Why do we see color? Designers intuitively know the answer to this question: It's to help us distinguish one thing from another and even to understand the thing itself. And what I mean by that is if you're looking at someone's face and they look very pale,

maybe with a yellow cast or a blue cast, we might understand that that person is sick or something is wrong; or, we're looking at a series of tomatoes, each one more ripe than the next – we are clued in to when the tomato is ready to eat. Maybe we're looking at a subway map and we see that each line is a different color, helping us to understand

which line we want to go on and where we want to go to. Along with shape, texture, movement, darkness and lightness, the more color that we could see, the more we could interpret about the world around us. By using color, designers are giving people a shorthand for how to use the products that they are designing. For example, if you are designing a pill bottle with pills inside,

the color of the bottle and the color of the pills themselves can distinguish not only from other pills that someone might be taking but even different dosages between them. Things like a traffic light, which, sure we could memorize what the order of the traffic light is, but having *color on top of order* gives us an incredibly quick and easy mechanism

for our brain to understand what to do next. Even things like sports uniforms – the reason that we have different colors for different uniforms is that it gives fans that immediate clue as to what to do when someone runs down one side of a field or another: do we cheer or do we boo? Just as important to the question of "Why do we see color?" is:

Why do we not see all the colors that are in our vision at once? And I'm not talking about ultraviolet or infrared or colors outside of the ability of our color vision. I'm talking about when we look at, for example, a red house and one side is in shadow and one side is in light; we're not seeing that house as partly dark red and partly pink.

We are just seeing it as a red house, and there's a very good reason for that. Just as I don't feel every sensation that is happening to my body every minute, like my glasses on the bridge of my nose – I'm not thinking about that until I actually think about it. My feet on the floor, that sensation – I'm not aware of it until I bring my mind to it, and throughout my body, there are all kinds of sensations going on all at once;

but it would be too much for the brain to be thinking about those things *all the time* on top of all the other sensations that we have, one of which is the light that is entering our eyes. So, if we were to register the millions of colors that are coming into our eyes all at once, our brain would just shut down; it would be too much; we wouldn't be able to make our way through the world, to make decisions, to move – all of these things. So, this becomes very important for designing because we have to decide

what we want the *focus* of people's attention to be. If we go back to this idea that color gives us information to help interpret the world, then we have to think about: "How are we using color so that it is giving us the right information to give us the right interpretation?" So, too much color, too much sensation, and then what follows we call *perception* – what we're actually

perceiving – can be confusing. Too little color might not give us enough information. We also take our clues about color from the *culture* where we live. So, for example, in the Western world, yellow is not a color that is particularly beloved, but in the Eastern world, it is.

So, the messaging that comes with the colors that you choose depend on *who* is receiving that color. We also have very personal associations with color which make it hard for designers because we don't know – unless we're designing for one person – what each person's reaction to a color is going to be. And lastly, we have these *biological reactions* to color, which at this point we know very, very little about.

So, when you go on the internet and you read, for example, that peach makes you hungry, the color peach, well, we don't know that at all – that's just a bunch of internet fake news. But we do know certain things about blue light, for example, or about the color red, and there are associations – biological – rooted in our biology in these colors that have an effect on us.

But taken together with the cultural and the personal, there's lots and lots of clues that are being given to a person, and these have to be accounted for in the design process – maybe not the personal part, but certainly the biological – the little that we know – and the cultural piece of it. So, to sum this up, why do we see color? We see color to help give us information so that we can make our way through the world

without harming ourselves and hopefully with helping ourselves. And color is this extraordinary tool, and it's one with a very fine point. It's one that was developed late in the development of the human brain. It is not essential to our being alive; take color-blind people, for example, but it's one that gives us the opportunity to be able to navigate quickly, easily and often with joy.

To use color theory effectively, consider the following tips from Joann Eckstut, co-author of 'What Is Color? 50 Questions and Answers on the Science of Color, in this video:

Understand the effect of light: Daylight constantly changes, affecting the colors we see. Changing the light source will change the color appearance of objects.

Consider the surroundings: Colors appear to change depending on the colors around them, a phenomenon known as simultaneous contrast.

Be aware of metamerism: Colors that match under one light source may not fit under another.

Remember that various factors such as light source and surrounding colors influence color, which is not a fixed entity. Being aware of these factors will prepare you to work effectively with color. Watch the full video for more insights and examples.

Color theory, as we know it today, is a culmination of ideas developed over centuries by various artists and scientists. However, one key figure in its development is Sir Isaac Newton, who, in 1666, discovered the color spectrum by passing sunlight through a prism. He then arranged these colors in a closed loop, creating the first color wheel. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe later expanded on this with his book "Theory of Colours" in 1810, exploring the psychological effects of colors.

Modern color theory has since evolved, incorporating principles from both Newton and Goethe, along with contributions from numerous other artists and researchers. To learn more about color theory, consider enrolling in the Visual Design - The Ultimate Guide course.

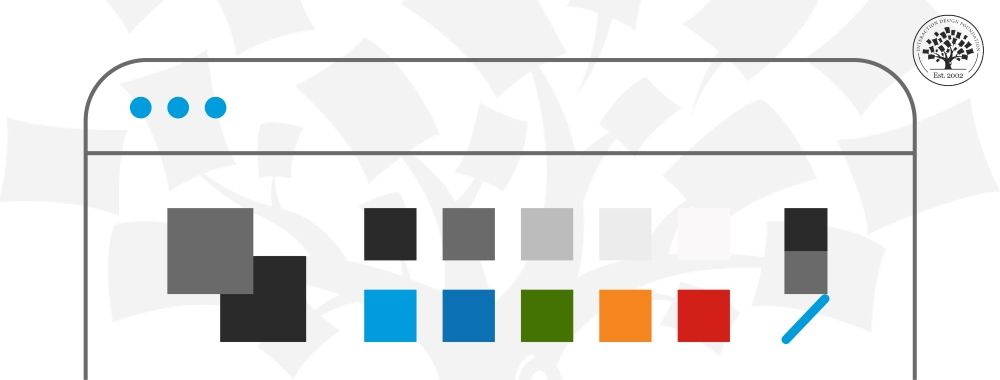

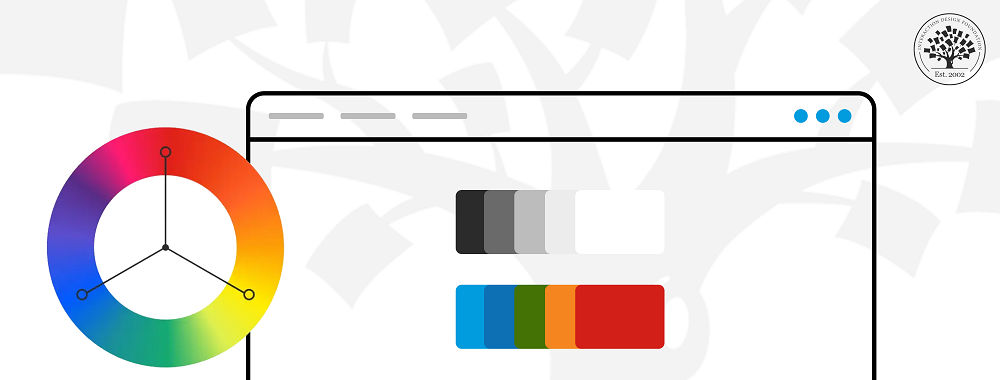

Understanding color theory might seem daunting at first, but it is manageable. Michal Malewicz emphasizes in the video below, that initially, a UX designer only needs three colors: a background color, a foreground (text) color, and an accent color.

If you're starting as a designer, you don't need a lot of colors, just as with fonts. If you're thinking, 'Okay, I have 60 million colors in that little picker, so let's try to use all of them!' that's not really the case. What you really need is a *background color*, a *foreground color* and an *accent color*. And there are some rules that you can then look up on your own later, like the *60-30-10 rule*, which is pretty useful. But, in general, what you need to really remember from this is that you need a *background color*, so in my case it's going to be white.

Then you need a *text color*, which is going to be some sort of black or dark gray, and the *accent color for the important actions*. And one thing that you can actually tweak here is to have that darker color instead of being pure black, add a little bit of that accent color. So, in our case, the blue to it, so it's just going to look a little bit more connected to the blue and it's just going to look better together. So, that's just one way. And you need *three colors* really to pull off most designs.

And you can start adding colors once you feel more comfortable with them. But when you're starting, really just the less colors the better because it's just much harder that way to screw it up. Two of the worst possible color combinations are mixing red with either very saturated blue or very saturated green. And if you look at it more closely depending on the type of screen that you have, you'll see that on the place where they kind of mix together,

that little line becomes a little bit fuzzy. If you look at it a little bit longer, it starts to hurt your eyes in some cases on some screens because this contrast of those colors works really, really bad together. So, if you want to make a Christmas app, for example, there are better ways to do it, but *generally avoid those color combinations* and *always test your colors if they're clashing that way*. So, you can just place one on top of the other and see if that fuzzy line appears on them.

And that's one way to actually test it – you know – *by eye*, just looking at it. If it looks good, then it looks good.

It's advisable to start with fewer colors and gradually incorporate more as you become comfortable. Also, avoid color combinations like red mixed with saturated blue or green, and always test your colors for contrast and accessibility. Mastering color theory ultimately comes down to practice and observation. If it looks good, then it is good. For a comprehensive learning experience, consider enrolling in the Visual Design - The Ultimate Guide course on Interaction Design Foundation. Enroll now

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Color Theory by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Color Theory with our course Visual Design: The Ultimate Guide .

In this course, you will gain a holistic understanding of visual design and increase your knowledge of visual principles, color theory, typography, grid systems and history. You’ll also learn why visual design is so important, how history influences the present, and practical applications to improve your own work. These insights will help you to achieve the best possible user experience.

In the first lesson, you’ll learn the difference between visual design elements and visual design principles. You’ll also learn how to effectively use visual design elements and principles by deconstructing several well-known designs.

In the second lesson, you’ll learn about the science and importance of color. You’ll gain a better understanding of color modes, color schemes and color systems. You’ll also learn how to confidently use color by understanding its cultural symbolism and context of use.

In the third lesson, you’ll learn best practices for designing with type and how to effectively use type for communication. We’ll provide you with a basic understanding of the anatomy of type, type classifications, type styles and typographic terms. You’ll also learn practical tips for selecting a typeface, when to mix typefaces and how to talk type with fellow designers.

In the final lesson, you’ll learn about grid systems and their importance in providing structure within design. You’ll also learn about the types of grid systems and how to effectively use grids to improve your work.

You’ll be taught by some of the world’s leading experts. The experts we’ve handpicked for you are the Vignelli Distinguished Professor of Design Emeritus at RIT R. Roger Remington, author of “American Modernism: Graphic Design, 1920 to 1960”; Co-founder of The Book Doctors Arielle Eckstut and leading color consultant Joann Eckstut, co-authors of “What Is Color?” and “The Secret Language of Color”; Award-winning designer and educator Mia Cinelli, TEDx speaker of “The Power of Typography”; Betty Cooke and William O. Steinmetz Design Chair at MICA Ellen Lupton, author of “Thinking with Type”; Chair of the Graphic + Interactive communication department at the Ringling School of Art and Design Kimberly Elam, author of "Grid Systems: Principles of Organizing Type.”

Throughout the course, we’ll supply you with lots of templates and step-by-step guides so you can go right out and use what you learn in your everyday practice.

In the “Build Your Portfolio Project: Redesign,” you’ll find a series of fun exercises that build upon one another and cover the visual design topics discussed. If you want to complete these optional exercises, you will get hands-on experience with the methods you learn and in the process you’ll create a case study for your portfolio which you can show your future employer or freelance customers.

You can also learn with your fellow course-takers and use the discussion forums to get feedback and inspire other people who are learning alongside you. You and your fellow course-takers have a huge knowledge and experience base between you, so we think you should take advantage of it whenever possible.

You earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you’ve completed the course. You can highlight it on your resume, your LinkedIn profile or your website.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!