Design Thinking: New Innovative Thinking for New Problems

- 1.1k shares

- 4 years ago

Innovation is the lifeblood of user experience (UX) design. As technological advancements continue to shape the digital world, designers aim to push boundaries to meet evolving user needs and expectations. To be innovative, designers rethink established norms, embrace new technologies and find creative solutions to complex problems.

UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains important points about innovation:

Let's talk about the difference between big, innovative changes to our product and small, incremental improvements, and the kinds of research that you might need in order to make these changes. We'll start with the incremental improvements because that's really the most frequent kinds of changes that we make as designers and researchers. While we all like to talk about designing things from scratch or making huge, sweeping changes,

the vast majority of people spend a lot of their time working on existing products and making them a little bit better every day. So, imagine you're building your new job marketplace to connect job seekers with potential employers. The product works. It's out in the real world being used by folks to find jobs every day. It's great! You made a thing that people are using, for money. Now, your product manager is looking at the metrics and they notice that a bunch of people are signing up and looking at jobs but they're not applying for anything.

Your job is to figure out why. So, what do you do? You can go ahead and pause the video and think about it for a minute if you want. There are a lot of different options you could go with here, but at the very least you're going to want to figure out the following things: Where are people stopping in the process and why are they stopping there? You'll probably want to dig into metrics a bit and figure out if folks do anything besides just look at jobs. Do they fill out their profile? Do they look at job details? Do they click the Apply button? And then do they give up at that point? Or do they never actually even get to that point?

Once you know where they're giving up, you'll probably do some simple observational testing of actual users to see what's happening when they do drop out. You'll probably also want to talk to them about why they're not applying. Maybe you'll find out that they get frustrated because they can't find jobs in their area. Well, that'd be great because that's really easy to fix; if that's the problem, maybe you can try letting them search for jobs near them. That's an *incremental change*. Now, what do we mean by that? It doesn't necessarily mean that it doesn't have a big impact on metrics.

Things like this can be hugely important for your metrics. If you manage to get lots more qualified candidates to apply to jobs, that's a huge win for the employers who are looking for great employees and it doesn't matter that it was just a simple button that you added. But it's not a wildly innovative change. In fact, it's a pretty standard feature on most job boards, and it's a very small improvement in terms of engineering effort, or at least it should be. If it isn't, there may be something wrong with your engineering department... which is a totally different course.

This change is *improving an existing flow*, rather than completely changing how something is done or adding a brand-new feature. OK, now, imagine that you're doing some observational research with your job applicants and you learn that for whatever reason they really don't have very much access to computers or they're not used to typing on a keyboard. This might lead to a very different sort of change than just searching for jobs in their area. Rather than making a small, incremental improvement to a search page, you might have to come up with an entirely different way for candidates to apply for jobs.

Maybe they need to film themselves using their phone cameras. This is a much larger change; it's *less incremental* since you're probably going to have to change or at least add a major feature to the entire job application process. You'll probably have to change how job seekers get reviewed by potential employers as well since they'll be reviewing videos rather than text resumes – which they might not be used to. This is a big change, but it's still incremental because it's not really changing what the product does.

It's just finding a new way to do the thing that it already did. OK, now, let's say that you have the option to do some really deep ethnographic research with some of your potential job applicants. You run some contextual inquiry sessions with them or maybe you run a diary study to understand all of the different jobs that they look at and learn why they are or aren't applying. Maybe in these deeper, more open-ended research sessions, you start to learn that the reason that a lot of potential job applicants drop out is because they just don't have the skills for the necessary jobs.

But what could *you* do about that? Well... our only options are either to find different applicants, find more suitable jobs or create some way to train our users in the skills that they need for the kinds of jobs that are available. All of those are really pretty big, risky ventures, but they just might be what we need to do to get more applicants into jobs. These are very big, and a couple of them are fairly innovative changes.

If the company pivots into, say, trainings and certifications or assessments, that definitely qualifies as innovation, at least for your product, but *how* does the research change for *finding* each of these sorts of things? Couldn't you have found out that applicants aren't qualified with the same types of research that you used to learn that they wanted to search by location? Maybe. Sometimes we find all sorts of things in very lightweight usability-type testing, but *more often* we find bigger, more disruptive things in deeper kinds of research – things like contextual inquiry, diary studies or longer-term relationships that we build with our customers.

Also, bigger, more disruptive changes often require us to do more in-depth research just to make sure that we're going in the right direction because the bigger it is the more risky it is. Let's say we ran some simple usability testing on the application process. That would mean we'd give applicants a task to perform, like find a job and apply to it. What might we learn from that? Well, that's the place where we'd learn if there were any bugs or confusing

parts of the system – basically, *can* somebody apply for a job? It takes more of a real conversation with a real user or a potential user to learn why they're not applying for jobs. It's not that one kind of testing is better than the other; it's that you can learn very different things with the different types of testing. Some types of research tend to deliver more in-depth learnings that can lead to big breakthrough changes, while other types of research tend to lead to smaller, more incremental but still quite useful and impactful changes. Both are extremely useful on agile teams, but you may find that the latter is more common just because many

agile teams don't really know how to schedule those big longer-term types of research studies, while running quick usability testing on existing software is quite easy and can even often be automated.

What makes the most popular digital products like mobile apps so successful? Is it that they solve problems in the most intuitive ways? Is it because they’re visually appealing with appropriate brand or industry colors and a minimalist look? Or maybe it’s because the brands’ user and market research departments zeroed in on the right parts of the customer experience—the ones they would need to create products that meet target users’ needs in full, and even dazzle them.

How a user interface (UI) guides users, the aspects of its visual design and how well it meets user needs are certainly vital factors—but one point in particular stands out for them as existing products. Before they went into product development, professionals had to work hard at generating ideas that found their way to the surface in what would become innovative solutions.

Household name Google's iconic, minimalist UI was once an innovation—and it remains popular because it stays relevant as a go-to for users around the world.

© Google, Fair Use

It might sound like a truism to state that design without innovation would be an oxymoron. However, if product design and innovation were not to connect, the results would include many bland retreads of a few original themes. There would be a near-total stagnation, with little choice and nothing substantial to differentiate brands in the marketplace. Fortunately, it’s human nature to advance—and UX design and innovation are synonymous. Designers and brands who aim to create successful design solutions for target audiences know that for successful service and product design, innovation—and the ability to remain innovative—is key.

Airbnb’s concept remains an innovation that rethinks accommodation and empowers users around the world to sample richer aspects of their hosts’ services.

© Airbnb, Fair Use

The digital landscape of the 21st century has delivered many innovations that users quickly take for granted as they absorb them into everyday life. Examples include increasingly sophisticated micro-interactions and micro-animations like swiping a touchscreen or a celebratory animation for completing a task. This landscape presents UX designers with a continuum of ongoing challenges and opportunities to shape the future of design. It’s a continuum that is constantly evolving—perhaps not so much like the frontier of a territory as it might be more like a winding road in an impossibly large forest, with many hidden caves and cavern systems, awaiting discovery. Many of these undiscovered areas will be loaded with treasures to deliver to users and profits to brands.

However, with innovation comes risk. Consider the conveniences of innovations like biometric technologies such as facial recognition and fingerprint scanning—and the potential challenges to users’ privacy they might present. As technology progresses further into different spheres of human life, there may even be some unforeseen risks that will take maturity in the industry—and experience with the technology involved—to identify in full. What’s more, a technology itself is not what appears in the marketplace: Products that innovatively tap technology do. Plus, how users receive a new product or service—and ideally adopt it—takes a design team’s careful consideration to plan for and accommodate.

CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers explains user adoption:

So, this user adoption lifecycle is something that we found to be true based on about a dozen years of analyzing our client app projects at Experience Dynamics, my UX consulting firm. And just so you understand what's happening is that with websites users judge a website; they visually judge it;

it's actually like a very precognitive – they're not even aware; it's a 50-millisecond kind of snap decision, and they look at a site and if it's beautiful they say, 'Oh, that must be easy to use.' But mobile apps don't get that kind of luxury, because it's – you know – you're downloading, installing something; you don't go into the App Store or Google Play Store and look at the look and feel of an app. It's more like what it'll do for you, and you're usually driven to it by a task such as... 'learn yoga' or 'discover somebody near me'

or 'install a VPN' or whatever the thing might be that you're using the App Store for. So, the next one on this kind of curve – so let's assume *visual judgment* is gone in mobile. *Cognitive judgment* is kind of the thinking. It's when I'm thinking like, 'Oh, what do I do? Where do I go?' And web apps are classic for falling into this kind of poor ease of use trap. Web applications you log in and it's like: 'Where's my tasks?

What do I do?' It's just classic with web applications – it seems like, anyway, or at least they started out that way. They've gotten better over the years and gotten more task-oriented. But the context there is that it's not like a consumer, like a website typically. With a web app, it is a B2B user – most likely it's a B2B user – or if it is a consumer, they're logging into their bank account or whatever, they're not there to look at the branding and the visuals. It's very much like 'I need to get my stuff done.'

So, that's what I mean by cognitive judgment. So, with mobile we don't really have that, because there isn't really the time to sort of even stop to think. It's much quicker, and that's why you have such a high uninstall ratio with apps. So, I like to say that this lifecycle sort of starts – I mean, it includes, of course it touches I guess very briefly on these other ones, but really starts with *emotional judgment*. And emotional judgment is – you know – 'Does this have what I need?

Is this going to do what I need it to do, like quickly?' So, you might try it; you might turn on the VPN; you might try chatting with someone, or you might begin searching and then find 'Ah – there's nothing here! Oh it's not connect— it's not fast! I'm not really sure if it's connecting! I'm not sure what's going on!' And that's the emotional judgment of that kind of unfulfilled desire, and of course you want it to look good; so, good visual judgment. Of course you want tasks to be apparent, so good cognitive judgment. But really the party with mobile starts on emotional judgment. So, it's like

make sure that you have a *very strong value proposition*, a *very strongly differentiated experience* where it's like, 'Oh, yeah, it looks great. I know exactly what to do, and it's got what I need.' If you get that established, then you can go to the sweet spot, which is this intention to return or intention to keep the app. And after that, after that trust is built and that reflection, which is,

Don Norman in his Emotional Design model talks about reflection as kind of like a 'Hmm, would I keep that? Would I recommend it to a friend? I like that app. I'm not going to uninstall it.' I almost think of it like the test is like, you could ask a user this as well: If you had to delete 10 apps, which of these 10 apps would you delete and see if yours is in that list? So, if the app is so important it's fulfilling a really important role, the user will keep it and try and keep it no matter what.

So, starting with that kind of sense of mobile is highly emotional, that you want users to stick with your app to keep it there, knowing that that's your design goal and that you want to kind of hit that triangle and make sure you don't lose your users, otherwise they'll leave or defect – that's really what user adoption for mobile is all about.

Another aspect of the place of innovation in design in this sense is the balance between a reliance on UI design patterns—established design norms that assure the designers who apply them well of reasonable chances of success for their brands—and pushing at the edges of what’s possible. The latter takes sparks of creativity—often generated during ideation sessions. It can lead a design team to adapt or rethink conventional approaches to digital products. Alternatively, they might inventively disrupt the status quo altogether and turn the usual ways of doing things upside down.

Watch our short video to understand more about UI design patterns:

User Interface Design Patterns are recurring components which designers use to solve common problems in interfaces. like, for example, when we think about those regular things that often are repeating themselves to kind of appear in, you know, in complex environments We need to show things that matter to people when they matter and nothing else. Right. it's just really sad what we see. Like, for example, if you look at Sears, right? Sears is just one of the many e-commerce sites, you know, nothing groundbreaking here. So you click on one of the filters and then the entire interface freezes

and then there is a refresh and you're being scrolled up. And I always ask myself, is this really the best we can do? Is really the best kind of interface for filtering that we can come up with, or can we do it a bit better? Because we can do it a bit better. So this is a great example where you have galaxies and then galaxies, you have all this filters which are in rows. Sometimes they take three rows, sometimes four or sometimes five rows. That's okay. Show people filters, show people buttons if they important show them.

Right. But what's important here, what I really like is we do not automatically refresh. Instead, we go ahead and say, "Hey, choose asmany filters as you like", right? And then whenever you click on show results, it's only then when you actually get an update coming up in the back. Which I think is perfectly fine. You don't need to auto update all the time. And that's especially critical when you're actually talking about the mobile view. The filter. Sure, why not? Slide in, slide out, although I probably prefer accordions instead.

And you just click on show products and it's only then when you return back to the other selection of filters and only when you click okay, show all products, then you actually get to load all the products, right? Designing good UI patterns is important because it leads to a better user experience, reduces usability issues, and ultimately contributes to the success of a product or application. It's a critical aspect of user centered design and product development.

Designers typically have a choice as to how much they can—or should—push at the edges of the established patterns and ways of doing things. Under the right conditions, they can showcase their expertise through design patterns that become truly their own. From there, they can score resounding wins for the brands they work for, the users they serve—and their own UX portfolios as examples of their creativity. They can include the evidence of how they came to access such imaginative heights in embracing new technologies and finding such creative solutions to complex problems through—for example—out-of-the-box thinking.

Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains how to think outside the box:

You've probably all heard that phrase 'thinking out of the box'. Everyone tells you, 'Think out of the box.' And it sounds so easy, and yet it's so difficult. If we're talking about theory and creativity, then we've got to think about *de Bono and lateral thinking*. So, if you're thinking out of the box, then lateral thinking is almost, not quite but almost, the same thing in different words.

And this idea of doing things that are breaking the mold, that are not following a line obviously covers a lot of creativity techniques, but particularly lateral thinking, de Bono's lateral thinking. The idea there is you've got, wherever you are, you've got your problem; you've got your start point. *Linear thinking*, in de Bono's terms, is very much about trying to follow the standard path, going along. So, if you're doing mathematics, you might pull the standard techniques off the shelf.

If you're writing a poem, you might be thinking line by line and thinking how each line fits and rhymes with the one before – if you're doing rhyming poetry, that is. So, it's all about following the same path of reasoning going on and on. *Lateral thinking is about trying to expand.* So, instead of following the same path of reasoning, are there *different places to start*? You know – are there different ways of thinking from the way where you are?

So, it's about trying to expand your idea of where you are outwards. So, that might be thinking of different solution strategies, so it might be thinking of different ways to start. Crucially, though, if you want to see out of the box or get out of the box, you actually often need to *see the box*. If you're literally in a cardboard box, you know you're in it. But mental boxes – you don't actually know you're in them. It's not that there's a cardboard wall and you don't go beyond it.

It's more like a hall of mirrors, so you never realize there's anything outside at all. Sometimes, *unusual examples* can help you see that. And that's, again, part of the reason for the bad ideas method, like *random metaphors* – things that, as soon as you've got something that *isn't in the box*, even if it's not a very good thing, it helps you to realize because you say, 'Well, *why* isn't this a good solution? Why doesn't it *work* as a solution?'

And as you answer that question about why, what you're doing is you're *naming that cardboard wall*. And once you've named the cardboard wall and you know it's there, you can start to think of what might be outside of that box but perhaps is a better solution. If you think about some of the analytic method— combining those, those are about building a map of the territory, which is very much about naming the box, naming the walls, naming the boundaries, and by naming them, by seeing from a distance what is there,

being able to then think of alternative solutions that are completely different. So, both alternative solutions help you to see the territory, help you to see the box. Of course, by seeing the box, that gives you the potential to have alternative solutions and actually you can iterate back and forth between those and hopefully build a better understanding of what is there and what is constraining you. If you understand what's constraining you, then you can start to break those constraints.

Innovation is both a process and a reward in a self-perpetuating system. Clients with ideas for new products and services—or exciting new variations on existing ones—seek designers who can mirror their passion and vision, and translate it to workable and bankable marketplace wins. In any case, the natural flow of—and need for—technological advancement reflects the nature of human users. What’s new and exciting in the marketplace needs to stay as novel and as exciting as it can—and needed and desired—long into the future. Design history features many examples of innovations that have fared differently over time, with technology such as MiniDisc players, Google Glasses and smartphones, and brands such as Apple, BlackBerry and Nokia.

Innovative UX design examples include Apple’s iPhone. This UX design innovation remains popular and exciting—Apple have their finger on the pulse of what smartphone users desire and know how to more than live up to the expectations of a loyal user base.

© Apple, Fair Use

Perhaps a better way to frame that question at first would be to ask what the risks are of not being innovative.

“Most innovations fail. And companies that don't innovate die.”

—Henry Chesbrough, Innovation Thought Leader who launched the "Open Innovation" paradigm

In the dynamic reality of modern design, brands know that it takes a unique approach just to survive in the market—let alone conquer a substantial share of it. The rise of the smartphone has offered a kind of stable playing field for UX and UI designers. Nevertheless, technology continues to evolve, and no brand can afford to be complacent in any case. Designers need to keep advancing so that they can:

The design thinking innovation process empowers designers and design teams to work out what and where the goal is.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

For true innovation, a UX design process such as design thinking is ideal. Since the design thinking process encourages such a vast exploration of the problem space and solution space, designers—and the team members they have ideation sessions with—can stand back and reapproach and reframe—and even radically depart from traditional ways of assessing—design problems and users’ needs and scenarios.

UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains important points about design thinking in this video:

Design thinking is a non-linear, iterative process that teams use to understand users, challenge assumptions, redefine problems, and create innovative solutions to prototype and test. It is most useful to tackle problems that are ill defined or unknown. In a rapidly changing world, organizations must be able to adapt and innovate quickly to survive. Design thinking is a powerful tool that can help organizations to do just that. By focusing on the user and their needs, he can help teams to develop creative solutions

that meet the real needs of the people they serve. The end goal of a design thinking process is to create a solution that is desirable, feasible and viable. This means that your product should satisfy the needs of a user, be feasible to implement and have a financial model as well. During the bulk of your design thinking process, you'll focus on desirability as you are concerned with testing your ideas and validating your hypothesis about your users.

Towards the end of your project, however, you should bring the focus to feasibility and viability so that your solution can be sustainable.

Divergent thinking techniques such as out-of-the-box thinking and bad ideas offer valuable leeway for design teams to get the distance to look at problems and contexts from new and unimagined perspectives. Once they access these new angles, team members can sift and sort the ideas they generate via convergent thinking and then weave workable insights into prototypes they can test.

Professor Alan Dix explains divergent and convergent thinking:

What I want to do now is talk about a few other kinds of divergent techniques. Creativity has two sides to it. There's being *novel* and being *useful*. There's a *divergent* side that's having lots and lots of bright ideas and a *convergent* side that tries to turn those ideas into something that's more useful and buildable.

Another component in the calculus of design innovation is the often-elusive goal of not just to attract users with a new design, but to keep them actively involved, interested and satisfied with a product that’s new, exciting and truly “different” to distinguish the brand that users will be loyal to. Designers therefore need a clear idea of the user journeys on which the people who will encounter new products or services will find themselves:

Frank Spillers explains key points about user journeys:

I wanted to just spend a little bit of time on the *user journey*. So, we can see how important user research is to creating really compelling value propositions and creating value for organizations that are trying to use service design to innovate, improve, streamline and smooth out. Well, there's nothing better to tackle that with than the user journey.

I wanted to just spend a little bit of time on this technique in case you didn't have that much experience with it or maybe you were doing journeys in a way that was different to the way I'm going to present to you. At least, I just wanted to share a template with you that can give you better access to what you're looking for. For me, now, a journey is something that you *build on*. So, first off it's your *customer journey*.

And on that is your service blueprint. And remember that the journey is going to reveal those cross-channel like, say, *breakpoints*, *pain points*, *disconnects* that you can map in the different *swim lane diagrams* – is the official term for a journey map. So, it comes from that – these swim lanes. And so, you'll have like maybe your channels here – you know – you'll have your user tasks here, pains and gains, or you can just have positive (+) or negative (-).

And I tend to change my user journeys, try and improve them, try and improve them. One of the problems that I find with journey maps – and they became very popular, I think around 2010, maybe, was the heyday of user journeys – 2010 / 2012, maybe. It was all about this beautiful big visualization. Let's be clear: A customer journey map is *not* about impressing your team

with really cool, big swim diagram visualizations with tons of little icons. It's a document like all deliverables in a human-centered design perspective. It should work for the internal teams that are using it as a decision-making document *as well*. The thing about the journey map that's particularly of value to the service designer is that it's happening across time

or across stages or across goals. So, the stages of, say, the life cycle – you know – you might have Research, Compare, Purchase, then the Return shopping. In other words, it's not just the purchase. A lot of conversion optimization and approaches to selling online just focus on this part here: the compare and purchase, or the funnel – if you will – the purchase funnel. And I think it's important to have the acquisition as much as the retention.

This is the conversion here. So, these two steps are the conversion steps. It's important to have *all* those steps represented. *Happy / sad moments* – you can have a little smiley face; *disconnects and breaks* – you know – so that you're like: "Ah! This is a break right here. They're on their phone, and they're researching, but the site's not responsive or it's *partially* responsive. And then, compare – when they go to compare, it only allows three items. So, it's like "Ohh!" – and then we have a quote from the user going:

"Why does this only allow (imitated mumbling)?!" – you know – something communicating the pain point. The other thing it's going to have is your reflections from your ethnography, from your personas. It's going to have those real-world contexts, basically. Instead of basically making it up and doing it internally, you're going to base it on user data. You'll also want to have *recommendations*. So, down here at the bottom you can have a list of recommendations

as well. This is an example of a journey map we created. And you can see the touch points we've added along the way. So, we have these different stages. We've got this – as the user walks through. So, we have Pre-apply, Apply, Post-apply. This is an online application journey. And we have the various channels that are occurring there. We've got the pain points represented. And the steps are:

Discover, Research, Apply, Manage and Dream. Discover was important because a lot of people didn't know that the offers were there. This is for getting an account. And basically the value proposition is you're going to have these offers – targeted offers – sent to you. So, the key is to find out how people are currently applying and at what stage makes sense to offer them these upsells, basically. And that's the value add that's being offered here.

User engagement is a key metric for understanding how users interact with a product or service and whether they find it valuable. Innovative UX design plays a vital role in this formula, as designers work to:

Improve usability: Innovative products should be easy to navigate and use effectively. They should have intuitive qualities that users can take to without detailed instruction.

Increase satisfaction: Users are more likely to come back to and recommend products that have innovative designs. They’re a sign of a forward-thinking company that looks to both the future and their users’ futures.

Boost the chances of success: Innovative UX design helps products fly high to reach solid goals, with more sales and strengthened customer loyalty.

Incorporate AI-driven personalization and real-time optimization: With advances in AI, designers can integrate it inventively into UIs and further boost user engagement—and their brands’ conversion rates.

Product Design Lead at Netflix, Nival Sheikh explains vital aspects about ethical AI:

Let's start with a definition about what ethical AI is. What ethical AI does is it seeks to promote fairness, minimize harm and align AI with human values and well-being. And if I'm a designer and I'm working in ethical AI, one of the questions that I really want to ask is how do I design artificially intelligent systems that follow ethical principles and society. When we think about the practice of building AI systems,

ethical AI is that practice that follows ethical and moral standards in society. But it is dynamic, right? As AI changes, ethical AI must change to keep momentum and to keep pace with the advent of AI technology. So one of the big questions that ethical AI asks as a bird's eye perspective of what AI is is what are the legitimate and illegitimate uses of A.I.?

One of the things that we talk about a lot in ethical AI is transparency which basically sounds is exactly what it sounds like. You're allowing users to understand how decisions are made in the AI systems that they're using. So, this and this really what it does is it builds trust with the user and it builds that relationship where it enables the user to really assess how the system behavior (It has a behavior for bias and fairness).

And it really allows them to see, you know, like what's going on in the background when they're using these AI systems. There’s accountability, which is basically that the designers, the developers, the organizations, basically every stakeholder that has some sort of stake in the matter, whether and even users, they should be held accountable for the impact and consequences of AI systems. So this means things like ease of troubleshooting,

ease of understanding, maybe for errors are there how to address those errors. Like those mechanisms should all be included within the system, within the AI system that they're using. And then there's fairness. So, outcomes should be fair and equitable for users. And by mitigating bias and addressing disparities in AI outcomes, this can be achieved. Definitely, easier said than done, as we'll see in a bit.

But this is the whole concept of just making sure that things are equitable and that outcomes aren't biased or favored towards one demographic or one region or one area or person or industry based off of another. or one region or one area or person or industry based off of another. And privacy. So, individuals have rights on their privacy and data, right? Especially we've been through a lot of like consumer data laws. So, the whole concept is built upon like these systems have to be built

to handle user privacy and data in a secure and ethical manner. And information should definitely be obtained consensually, which not only means that, like me, as a user, I'm giving my data and consenting to my data being given. But I also understand what it means to permission a system to to have my data. Like are they going to sell it? What are they going to do with it? I should, as a user, should have a very thorough understanding of that. And so that understanding should be accessible amongst everyone.

That's basically the idea of privacy and ethical AI.

Innovation is a pressing need for the survival and sustainable growth of companies, and innovative UX design helps organizations:

Stand out in a competitive market: A brand that can offer exceptional and user-centered experiences can enjoy sustainable advantages over competitors.

Attract new clients: For agencies and designers, it’s a massive asset to have original design patterns to showcase to potential clients. The evidence of this expertise can lead them to work on more exciting projects with brands that seek to differentiate themselves.

Reflect company values: Innovative products often call for equally innovative digital properties to support them. That makes designers who create innovative designs more attractive to forward-thinking companies. One of the most vital values a brand can exhibit—and an aspect that designers mustn’t forget as they innovate—is a commitment to accessibility and inclusive design.

Watch our video to understand the vital nature of accessibility in design:

Accessibility ensures that digital products, websites, applications, services and other interactive interfaces are designed and developed to be easy to use and understand by people with disabilities. 1.85 billion folks around the world who live with a disability or might live with more than one and are navigating the world through assistive technology or other augmentations to kind of assist with that with your interactions with the world around you. Meaning folks who live with disability, but also their caretakers,

their loved ones, their friends. All of this relates to the purchasing power of this community. Disability isn't a stagnant thing. We all have our life cycle. As you age, things change, your eyesight adjusts. All of these relate to disability. Designing accessibility is also designing for your future self. People with disabilities want beautiful designs as well. They want a slick interface. They want it to be smooth and an enjoyable experience. And so if you feel like

your design has gotten worse after you've included accessibility, it's time to start actually iterating and think, How do I actually make this an enjoyable interface to interact with while also making sure it's sets expectations and it actually gives people the amount of information they need. And in a way that they can digest it just as everyone else wants to digest that information for screen reader users a lot of it boils down to making sure you're always labeling

your interactive elements, whether it be buttons, links, slider components. Just making sure that you're giving enough information that people know how to interact with your website, with your design, with whatever that interaction looks like. Also, dark mode is something that came out of this community. So if you're someone who leverages that quite frequently. Font is a huge kind of aspect to think about in your design. A thin font that meets color contrast

can still be a really poor readability experience because of that pixelation aspect or because of how your eye actually perceives the text. What are some tangible things you can start doing to help this user group? Create inclusive and user-friendly experiences for all individuals.

User preferences and expectations are constantly changing. Innovative UX and UI designs help meet these evolving needs since they can:

Adapt to technological changes: Most people quickly adapt to technological advancements, making them more open to innovations that positively contribute to their lives.

Create intuitive interfaces: Innovations like kebab menus have long since become established web design patterns—to simplify and declutter interfaces, especially on mobile sites.

Embrace emerging technologies: Technologies like artificial intelligence (AI), voice interfaces, blockchain, IoT and wearables offer new ways to enhance user experiences and meet changing expectations.

When a brand’s design team applies this framework well, it can afford to consider innovation as a learning process embedding design thinking—and take the time to arrive at the best solutions.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Here are some notable ones:

Artificial intelligence and machine learning (ML) have become essential tools in UX design. They’ve revolutionized the way designers create, personalize and optimize user experiences. AI and ML algorithms can:

Analyze large volumes of user data to identify patterns and insights.

Predict user behavior and anticipate needs and preferences.

Optimize the user journey for a more intuitive experience with tailored content.

When mindful and innovative designers integrate AI into UIs, they can greatly boost user engagement and conversion rates through personalization and real-time optimization. AI-powered tools also automate tedious tasks and let designers focus on more creative and strategic work from higher altitudes.

The potential for AI in innovative design is immense—and calls for responsible and ethical study and application.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Voice and gesture-based interfaces have evolved to highly sophisticated levels. Smartphone screens and Alexa devices are prime examples of how embedded these technologies are as staples of design and household names. What’s more, the advent of AI and machine learning has taken these interfaces to new heights, and made them increasingly sophisticated and user-friendly.

Key considerations for designing voice- and gesture-based interfaces include:

Natural language processing and speech recognition for voice interfaces.

Context-appropriate design based on the user's environment and tasks.

Intuitive and easy-to-perform gestures for gesture-based interfaces.

These interfaces offer many benefits that modern users have become used to—and that users expect to develop further and in new ways for their use—such as hands-free interaction and improved accessibility for users with disabilities. However, designers must be mindful of potential challenges such as providing adequate feedback, establishing good user experiences and addressing privacy concerns.

Augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) are continuing to transform UX design and users’ lives. From their early days as novelty experiences, for example, innovative AR and VR designs have grown to become ingrained in the popular psyche. Immersive and interactive experiences integrate digital data with the user's environment in real-time, allowing for more natural and intuitive interactions.

Watch Frank Spillers explain fascinating points about AR and its importance in the modern design world:

What is AR? Well, the old definition is that, you know, you see a visualization with an iPad or a phone and it kind of something just pops up, a static visualization. The new definition of AR utilizes technologies that embody spatial mapping that actually map out the room and uses headsets more like this headset where you're looking around and you're have more contact than just through your phone.

So you have holograms and stories or narratives that actually merge with the actual environment, and that's the exciting potential of AR designing for augmented reality. It's about deepening the meaning of real and augmented objects and contexts that is playful and helps guide your discovery that you can visualize and have intuitive discovery and manipulation of objects or content,

and but that it allows you to extend your cognitive abilities to think, to decide, to imagine. It couples with reality to create more meaning. And finally, that is collaborative. And the question is, what's the difference between VR? VR you wear a headset and you're fully underneath that head mounted display, whereas AR your have something that keeps you in contact with the real world.

Key aspects of AR and VR for designers to keep innovating include in how they can:

Create tridimensional interfaces for more natural interactions.

Develop virtual prototypes for early user feedback and testing.

AR and VR technologies can also leverage sensors and AI to collect data about user behavior and preferences, which can enable highly personalized experiences. These immersive technologies continue to open up new possibilities for data visualization, accessibility and gesture-based interactions. So, they’re prime areas of attention for designers to focus pushing at the boundaries of—and help users emerge into powerfully helpful new conveniences that may become staples in everyday life.

Author and UX Pioneer, known as the Father of UX Design, Don Norman explains important points about the future of AR and VR in design:

Well, I'm a fan of both – basically VR and AR are the two major categories, and the rest are specializations. I'm a fan of both. I think living in an artificial world is really engaging. I've been doing it for 20 years. Let me explain that. I have been seeing this in research laboratories for about 20 years and experiencing it in wonderful, wonderful experiences. And it isn't yet up for real time; it's just getting there, just beginning;

it's got a few more years to go, but I believe that's going to be very important. It's already important for *training* people. It's already used in medicine, for example. And it's already used in repair – learning how to repair things. *Augmented* is also very very valuable because with virtual reality, it's your *own new world* with augmented, I'm *the real world* but I have things, so augmented is really great for people trying to repair something

because I go to the thing that is broken and there on top of it I can see instructions or arrows pointing to what I should look at next and so on. But again it's just – at Apple, when I was at Apple 20 years ago, we were doing this; we were already trying to do this, but the technology wasn't good enough. And I think that it's going to be very powerful.

Designers encounter the professional face of innovation in many aspects of their lives, and it’s here where they can flex their imaginations and stoke powerful engines of creativity:

Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains important points about the nature of creativity:

What is creativity? Is it something that you just sort of *wait for* to fall on you from above? Or is it something you *work at*? Do you all have those moments when you you know you need a spark of creativity? You're in the midst of designing something; you're trying to make a new website; you're trying to make a new application; you're trying to work out how to evaluate something

that's hard to evaluate – perhaps the way people feel or something like this. And you want that *moment of inspiration*, and does it come when you need it? Of course it doesn't! The model we have of creativity tends to be about these moments of genius. And you already heard about, I think, the 3M story, the Post-it Notes. You know – imagine if you'd had that idea to use this sort of magic glue on the back to create Post-it Notes; how much money there has been on Post-it Notes. Or Philippe Starck and the – well, we all know the lemon juicer is not perhaps all it's cooked up to be,

that it dribbles all over your fingers and stuff, but boy is it iconic! And everybody who's anybody in design would like one of those lemon squeezers sitting on their kitchen worktop! We have this idea of creativity as a genius activity. It might be Steve Jobs in Apple or some of these designers we're looking at here, perhaps Einstein. But is that the full story? Certainly that's the sort of way it seems if you look at sort of

Western traditions of thinking about these things. Going way back to the Greeks, you've got the Muses, the different arts, and the idea that somehow or other this inspiration comes from the Muses up in Olympus and gives you these bright ideas, whether it's poetry or whether it's music ... or web design! So, is that the real story? Let's look a little bit back at these two we've been looking at. First of all, let's look back at the Post-it Notes.

The story is a little bit more complicated; it's not just – you probably know a little bit about this; it wasn't just a moment of inspiration. The guy who was trying to design these things – well, he *wasn't* trying to design these things; the guy was called Spencer Silver; 1968, and he's trying to design a really good glue. And he makes his glue, and he puts it on the back of some paper, and he sticks it to something, and it just... pulls straight off again. Whatever he sticks it to, it's rubbish.

Now, I don't know if you've done this. You've been scribbling away at something; you've got lots of ideas, perhaps on your napkin... and you're about to throw it away. When you're about to do that, when you're about to throw it in the bin, pull it out again, have another peek because you never know when you might have a *moment of genius*. Spencer Silver was like this, but he knew there was something about this.

There was something about this he felt could be useful. He spent five years going around 3M talking to people, giving seminars and talks and talking about this solution in need of a problem. And then, in 1974, a guy called Arthur Fry was in one of these talks and came back to Spencer and said, 'I have an idea.'

Five years, two people, and an idea that could have been.... And that would throw the whole lot away in the bin before it ever started. Okay, let's look at the lemon squeezer now. So, Philippe Starck – I think it was in Italy, but he's in a restaurant somewhere. And the story is he's thinking about lemon squeezers; he has this sort of inspiration of a squid,

and hence we get the iconic lemon squeezer. But of course, first of all that's not built just on that meal time. He knows about lemon squeezers; he's seen lots of lemon squeezers, lemon squeezers which have some of the suggestions – especially if you look at those kind that you do this to – of the one on the bottom, or be it the other way around; maybe it would work better if you have the sharp end up. But even that – it's not as simple as that. He wrote down on, perhaps it was a tablecloth – certainly in some of these Italian restaurants you get paper tablecloths

that get taken away, thrown away at the end. But this tablecloth has been preserved, or this napkin has been preserved. And when you look at that, you see things, images, some of them which look pretty much like standard lemon squeezers, and gradually shifting. The order is not so clear. But it looks pretty much like actually the squid came quite late in the day. So, when he tells the story, of course the squid is hot in his imagination, but when you actually look at the trace of the design,

there were a lot of stages, goodness knows how many sketches, on this very small piece of paper that eventually came up with this idea. So, even something that took quite a short amount of time, unlike the 3M Post-it Notes, which took five years to gestate, this happened quite quickly. But even, so there was quite an *evolutionary process* in actually coming up with the idea. So, the question is – can we have *techniques* to help us do this kind of thing?

Not necessarily to turn us into immediate magic geniuses, but to actually get reasonable creative ideas when we need them.

At the same time, the workplace is the main area for designers to explore and tap innovative insights. So, it’s vital to:

Designers and the teams they ideate and iterate with need an environment that’s conducive to creativity—one that doesn’t stifle wild-sounding notions with judgments. This involves thinking outside the box and developing exciting ideas for user interfaces that offer exceptional experiences. To encourage new and even seemingly crazy ideas among team members can lead to innovative breakthroughs. It's important to remember that great ideas often sound unconventional at first.

To stimulate creativity, designers can:

Use design thinking exercises to encourage collaboration and facilitate problem-solving.

Employ structured but open-ended frameworks that foster creativity.

Challenge assumptions and explore diverse perspectives.

Treat uncertainty as an opportunity for meaningful and creative solutions.

Professor Alan Dix explains the bad ideas approach to innovation:

In this video, I'm going to give you an exercise to do. It's going to be an exercise in *bad ideas*. This is where I tip your brain towards madness. But, hopefully – the boundary between creativity and genius and total madness is often said to be a thin one; so, by pushing you a little towards madness, I hope to also push you a little towards creativity.

And hopefully, you can control the madness that comes there. But we'll see as it goes along. So, what I want you to do is – you know how hard it is to think of good ideas; everybody says, "Ah! Let's have a brainstorming session and have lots of ideas!" and (sound effect), right? So, if it's so hard to think of good ideas, why not think of a *bad idea*? So, what I'd like you to do as an exercise is just to think of a bad idea or a silly idea, a completely crazy idea.

Now, it might be about something that you're doing at the moment. Or it might be a particular problem you've got. And so, what would be a really bad idea... for sending notifications to people about something you want to get them engaged in? Perhaps you could send them an email every three seconds or something like that! So, it could be that kind of bad idea, or it could be just an idea from the world.

And it could be a Heath Robinson sort of bad idea – something that's complex and arcane and that. Or perhaps – and this is probably a good one to start with – just an *oxymoron*. So, something like a chocolate teapot, so something that appears to be really crazy, really silly; a car without an engine – I remember once in a session we had this – that doesn't seem like a good idea. So, you've got your bad idea – it may be a chocolate teapot

or it may be the car with no engine or something like that. What I want you to do now is – I'm going to take you through some prompt questions. First of all, this was a bad idea – the reason you chose it was because it was a bad idea. So, what I want you to do is say to yourself, "What is bad about this idea?" So, think of the car without an engine. What's bad about a car without an engine? Well, it doesn't have an engine; it's obvious, right?

So, you start off with that. Now, you might think a bit more. But then I want you to dig and say, "Well, *why* is that a bad idea?" Well, it's not got an engine – it can't go anywhere. Then dig a bit back further; so, are there things that you can think of that are like that, that have that property? So, for instance, a car without an engine can't go anywhere. Are there things that can't go anywhere that's actually a good idea? Well...

a garden shed: a garden shed doesn't go anywhere, but that's not a bad idea. And, in fact... you might want to have something that can't be stolen; you don't want that to go anywhere. So, that's not a bad idea. So, if you can think of things that appear to share the bad thing but actually aren't bad, what's the difference? Why is not having an engine, why is not being able to go anywhere bad for the car but not bad for the garden shed?

And as you dig into this, hopefully you start to understand better these things. You can also go the other way around. So, you *know* this is a bad idea, but maybe there's something good about it. It hasn't got an engine; it's not polluting. Wow, we've got a green car! It will be green because all the moss will grow on it because it doesn't drive anywhere, but – you know – "This is good, surely?!"

So, then you can think, "Well, okay, if this is a good thing" – you can do the same sort of thing: "Why is that a good thing?" Well, it doesn't choke you with its pollution. If you're finding this difficult – and particularly this is true about the bad idea bit – you want to say... with the bad idea, you want to change that bad thing into a good thing; so, this is whether you want to find a good thing in the bad idea or you want to find a good use for the thing you've identified that's bad – you might try a *different context*; so...

if you take the car off the road and put it perhaps into something where it's moved along by something else – perhaps sitting on the back of a lorry... why, you might want that – well, you might want it so you can easily move your car. You might put it onto something that's dragged along. So, you sometimes change the context and suddenly something that seemed bad suddenly is not so bad. So, the final thing you can do with your bad idea is *turn it into a good idea*.

Now, you might have already done this as part of that process. So, what's *good*? When you've identified something that's good about it, like the car, that it wasn't polluting, try to hold on to that – try to keep that and retain that good feature. But where you found the things and you really dug down to *why something's bad*, not just the superficial – you know – it doesn't have an engine; well, that's not bad in itself,

but the fact that means you can't drive anywhere in it; okay, that's bad. So, can you change that badness but still retain the non-pollutingness? So, perhaps we're going to have a truly green car. Perhaps we're going to have roads with sort of little wires you connect into and – you know – a bit like Scalextric cars, so you can drag the cars along so they don't have an engine and they're being powered elsewhere. You may, I said, *change the context entirely* – so, instead of it being a car for driving around in

– well, I've already mentioned this one – stick your chickens in it and it suddenly becomes a hen coop. And I think if you go around the the world, you'll find a lot of old cars usually actually with their engines still sitting in them that are being used as hen coops. If you had a *complex idea* – and this is true, it could be for a simple idea, but in doing your thinking, there might be just something about it, something small;

it wasn't necessarily the whole thing. So, actually – you know – the idea of the gap in the engine; perhaps you decided that would be really good actually having the engine not there because you could put things in the front, and for whatever reason, you think it's easier to put things in the front than the back. So, perhaps that becomes your idea – that actually, you'd quite like to be able to put your luggage in the front of the car; you'd like more room in the car for luggage. And then perhaps you'll put an engine back in the car, but thinking about

how you actually improve access for luggage. If you've had one of those Heath Robinson complex ideas, Wallace and Gromit-like ideas, then actually you may not be trying to make the whole thing into a good idea; but within it, some little bit of that complex mechanism might be something that you've thought about; you've realized and suddenly think, "Ahh!" and do something just with that. And I'll leave you with a glass hammer!

User-centered design (UCD) is crucial for creating valuable and innovative products or services. To practice it, designers put their users’ needs and wants first, make data-driven decisions and create intuitive designs that satisfy—and, ideally, exceed—user needs. So, designers should:

Conduct thorough user research to gain insights into users' core needs.

Observe users in their natural environments, to understand their preferences and values.

William Hudson explains essential points about user research:

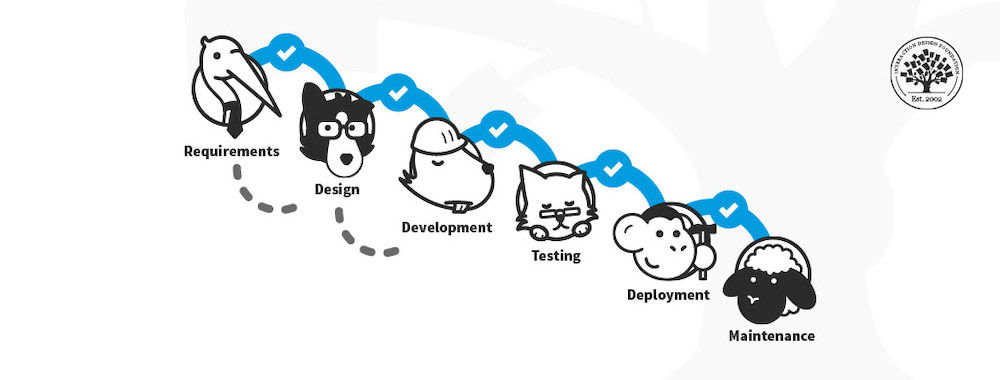

User research is a crucial part of the design process. It helps to bridge the gap between what we think users need and what users actually need. User research is a systematic process of gathering and analyzing information about the target audience or users of a product, service or system. Researchers use a variety of methods to understand users, including surveys, interviews, observational studies, usability testing, contextual inquiry, card sorting and tree testing, eye tracking

studies, A-B testing, ethnographic research and diary studies. By doing user research from the start, we get a much better product, a product that is useful and sells better. In the product development cycle, at each stage, you’ll different answers from user research. Let's go through the main points. What should we build? Before you even begin to design you need to validate your product idea. Will my users need this? Will they want to use it? If not this, what else should we build?

To answer these basic questions, you need to understand your users everyday lives, their motivations, habits, and environment. That way your design a product relevant to them. The best methods for this stage are qualitative interviews and observations. Your visit users at their homes at work, wherever you plan for them to use your product. Sometimes this stage reveals opportunities no one in the design team would ever have imagined. How should we build this further in the design process?

You will test the usability of your design. Is it easy to use and what can you do to improve it? Is it intuitive or do people struggle to achieve basic tasks? At this stage you'll get to observe people using your product, even if it is still a crude prototype. Start doing this early so your users don't get distracted by the esthetics. Focus on functionality and usability. Did we succeed? Finally, after the product is released, you can evaluate the impact of the design.

How much does it improve the efficiency of your users work? How well does the product sell? Do people like to use it? As you can see, user research is something that design teams must do all the time to create useful, usable and delightful products.

Create personas that represent principal user groups to provide a shared understanding among team members.

Professor Alan Dix explains important points about personas:

Personas are one of these things that gets used in very, very many ways during design. A persona is a rich description or description of a user. It's similar in some sense, to an example user, somebody that you're going to talk about. But it usually is not a particular person. And that's for sometimes reasons of confidentiality.

Sometimes it's you want to capture about something slightly more generic than the actual user you talked to, that in some ways represents the group, but is still particular enough that you can think about it. Typically, not one persona, you usually have several personas. We'll come back to that. You use this persona description, it's a description of the example user, in many ways during design. You can ask questions like "What would Betty think?"

You've got a persona called / about Betty, "what would Betty think" or "how would Betty feel about using this aspect of the system? Would Betty understand this? Would Betty be able to do this?" So we can ask questions by letting those personas seed our understanding, seed our imagination. Crucially, the details matter here. You want to make the persona real. So what we want to do is take this persona, an image of this example user, and to be able to ask those questions: will this user..., what will this user feel about

this feature? How will this user use this system in order to be able to answer those questions? It needs to seed your imagination well enough. It has to feel realistic enough to be able to do that. Just like when you read that book and you think, no, that person would never do that. You've understood them well enough that certain things they do feel out of character. You need to understand the character of your persona.

For different purposes actually, different levels of detail are useful. So I'm going to sort of start off with the least and go to the ones which I think are actually seeding that rich understanding. So at one level, you can just look at your demographics. You're going to design for warehouse managers, maybe. For a new system that goes into warehouses. So you look at the demographics, you might have looked at their age. It might be that on the whole that they're older. Because they're managers, the older end. So there's only a small number under 35. The majority

are over 35, about 50:50 between those who are in the sort of slightly more in the older group. So that's about 40 percent of them in the 35 to 50 age group, and about half of them are older than 50. So on the whole list, sort of towards the older end group. About two thirds are male, a third are female. Education wise, the vast majority have not got any sort of further education beyond school. About 57 percent we've got here are school.

We've got a certain number that have done basic college level education and a small percentage of warehouse managers have had a university education. That's some sense of things. These are invented, by the way, I should say, not real demographics. Did have children at home. The people, you might have got this from some big survey or from existing knowledge of the world, or by asking the employer that you're dealing with to give you the statistics. So perhaps about a third of them have got children at home, but two thirds of them haven't.

And what about disability? About three quarters of them have no disability whatsoever. About one quarter do. Actually, in society it's surprising. You might... if you think of disability in terms of major disability, perhaps having a missing limb or being completely blind or completely deaf. Then you start relatively small numbers. But if you include a wider range of disabilities, typically it gets bigger. And in fact can become

very, very large. If you include, for instance, using corrective vision with glasses, then actually these numbers will start to look quite small. Within this, in whatever definition they've used, they've got up to about 17 percent with the minor disability and about eight percent with a major disability. So far, so good. So now, can you design for a warehouse manager given this? Well,

you might start to fill in examples for yourself. So you might sort of almost like start to create the next stage. But it's hard. So let's look at a particular user profile. Again, this could be a real user, but let's imagine this as a typical user in a way. So here's Betty Wilcox. So she's here as a typical user. And in fact, actually, if you look at her, she's on the younger end. She's not necessarily the only one, you usually have several of these. And she's female as well. Notice only up to a third of our warehouse ones are female. So

she's not necessarily the center one. We'll come back to this in a moment, but she is an example user. One example user. This might have been based on somebody you've talked to, and then you're sort of abstracting in a way. So, Betty Wilcox. Thirty-seven, female, college education. She's got children at home, one's seven, one's 15. And she does have a minor disability, which is in her left hand. And it's there's slight problem in her left hand.

Can you design, can you ask, what would Betty think? You're probably doing a bit better at this now. You start to picture her a bit. And you've probably got almost like an image in your head as we talk about Betty. So it's getting better. So now let's go to a different one. You know, this is now Betty. Betty is 37 years old. She's been a warehouse manager for five years and worked for Simpkins Brothers Engineering for 12 years. She didn't go to university, but has studied in her evenings for a business diploma.

That was her college education. She has two children aged 15 and seven and does not like to work late. Presumably because we put it here, because of the children. But she did part of an introductory in-house computer course some years ago. But it was interrupted when she was promoted, and she can no longer afford to take the time. Her vision is perfect, but a left hand movement, remember from the description a moment ago, is slightly restricted because of an industrial accident three years ago.

She's enthusiastic about her work and is happy to delegate responsibility and to take suggestions from the staff. Actually, we're seeing somebody who is confident in her overall abilities, otherwise she wouldn't be somebody happy to take suggestions. If you're not competent, you don't. We sort of see that, we start to see a picture of her. However, she does feel threatened – simply, she is confident in general – but she does feel threatened by the introduction of yet another computer system. The third since she's been working at Simpkins Brothers. So now, when we think about that, do you have a better vision of Betty?

Do you feel you might be in a position to start talking about..."Yeah, if I design this sort of feature, is this something that's going to work with Betty? Or not"? By having a rich description, she becomes a person. Not just a set of demographics. But then you can start to think about the person, design for the person and use that rich human understanding you have in order to create a better design.

So it's an example of a user, as I said not necessarily a real one. You're going to use this as a surrogate and these details really, really matter. You want Betty to be real to you as a designer, real to your clients as you talk to them. Real to your fellow designers as you talk to them. To the developers around you, to different people. Crucially, though, I've already said this, there's not just one. You usually want several different personas because the users you deal with are all different.

You know, we're all different. And the user group – it's warehouse managers – it's quite a relatively narrow and constrained set of users, will all be different. Now, you can't have one persona for every user, but you can try and spread. You can look at the range of users. So now that demographics picture I gave, we actually said, what's their level of education? That's one way to look at that range. You can think of it as a broad range of users.

The obvious thing to do is to have the absolute average user. So you almost look for them: "What's the typical thing? Yes, okay." In my original demographics the majority have no college education, they were school educated only. We said that was your education one, two thirds of them male – I'd have gone for somebody else who was male. Go down the list, bang in the centre. Now it's useful to have that center one, but if that's the only person you deal with, you're not thinking about the range. But certainly you want people who in some sense

cover the range, that give you a sense of the different kinds of people. And hopefully also by having several, reminds you constantly that they are a range and have a different set of characteristics, that there are different people, not just a generic user.

Start early in the design process with wireframes, prototyping and usability testing to keep a valuable user experience core at the heart of all that they design.

Watch as Alan Dix explains prototyping and why it’s important:

So, why do you need prototyping? Well, we never get things right first time. It's about getting things *better* when they're not perfect and also *starting in a good place*. Maybe if I'm going to make a wall for a house, I know exactly how big the wall should be. I can work out how many bricks I need. I can make it exactly the right size.

So, I can get it right first time. It's important to. I don't want to knock the wall down and retry it several times. However, there I have a very clear idea of what I'm actually creating. With people involved, when you're designing something for people, people are not quite as predictable as brick walls. So, we *don't* get things right first time. So, there's a sort of classic cycle – you design something, you prototype it,

and that prototyping might be, you might sort of get a pad of paper out and start to sketch your design of what your interface is going to be like and talk through it with somebody. That might be your prototype. It might be making something out of blue foam or out of cardboard. Or it might be actually creating something on a device that isn't the final system but is a "make-do" version, something that will help people understand.

But, anyway, you make some sort of prototype. You give it to real users. You talk to the real users who are likely to be using that about it. You evaluate that prototype. You find out what's wrong. You redesign it. You fix the bugs. You fix the problems. You mend the prototype, or you make a different prototype. Perhaps you make a better prototype, a higher-fidelity prototype – one that's closer to the real thing. You test it again, evaluate it with people, round and round and round. Eventually, you decide it's good enough. "Good enough" probably doesn't mean "perfect", because we're not going to get things perfect, ever.

But "good enough" – and then you decide you're going to ship it. That's the story. In certain cases in web interfaces, you might actually release what in the past might have been thought of as "a prototype" because you know you can fix it, and there might not be an end point to this. So, you might in delivering something – and this is true of any product, actually – when you've "finished" it, you haven't really finished, because you'll see other problems with it, and you might update it

and create new versions and create updates. So, in some sense, this process never stops. In one way, it's easy to get so caught up with this *iteration* – that is an essential thing – that you can forget about actually designing it well in the first place. Now, that seems like a silly thing to say, but it is easy to do that. You know you're going to iterate anyhow. So, you try something – and there are sometimes good reasons for doing this –

you might have *so little* understanding of a domain that you try something out to start with. However, then what you're doing is creating a *technology probe*. You're doing something in order to find out. Of course, what's easy then to think about is to treat that as if it was your first prototype – to try and make it better and better and better. The trouble is – if it didn't start good, it might not end up very good at the end, despite iteration. And the reason for that is a phenomenon that's called *local maxima*.

So, what I've got here is a picture. You can imagine this is a sort of terrain somewhere. And one way to get to somewhere high if you're dumped in the middle of a mountainous place – if you just keep walking uphill, you'll end up somewhere high. And, actually, you can do the opposite as well. If you're stuck in the mountains and you want to get down, the obvious thing is to walk downhill. And sometimes that works, and sometimes you get stuck in a gully somewhere. So, imagine we're starting at this position over on the left. You start to walk uphill and you walk uphill and you walk uphill.

And, eventually, you get onto the top of that little knoll there. It wasn't very high. Now, of course, if you'd started on the right of this picture, near the *big* mountain, and you go uphill and you go uphill and you go uphill and you get uphill, you eventually end up at the top of the big mountain. Now, that's true of mountains – that's fairly obvious. It's also true of user interfaces. *If you start off* with a really dreadful design and you fix the obvious errors,

*then you end up* with something that's probably still pretty dreadful. If you start off with something that's in the right area to start with, you do better. So, the example I've put on the slide is the Malverns. The Malverns are a set of hills in the middle of the UK – somewhere to the southwest of Birmingham. And the highest point in these hills is about 900 feet. But there's nothing higher than that for miles and miles and miles and miles.

So, it is the highest point, but it's not *the* highest point, certainly in Britain, let alone the world. If you want to go really high, you want to go to Switzerland and climb up the Matterhorn or to Tibet and go up Mount Everest, up in the Himalayas, you'll start somewhere better, right? So, if you start – or on the island I live on, on Tiree, the highest point is 120 meters. So, if you start on Tiree and keep on walking upwards, you don't get very high.

You need to start in the *right* sort of area, and similarly with a user interface, you need to start with the *right* kind of system. So, there are two things you need for an iterative process. You need a *very good starting point*. It doesn't have to be the best interface to start with, but it has to be in the right area. It has to be something that when you improve it, it will get really good. And also – and this is sort of obvious but actually is easy to get wrong – you need to understand *what's wrong*. So, when you evaluate something, you really need to understand the problem.

Otherwise, what you do is you just try something to "fix the obvious problem" and end up maybe not even fixing the problem but certainly potentially breaking other things as well, making it worse. So, just like if you're trying to climb mountains, you need to start off in a good area. Start off in the Himalayas, not on Tiree. You also need to know which direction is up.

If you just walk in random directions, you won't end up in a very high place. If you keep walking uphill, you will. So, you need to *understand where to start* and *understand which way is up*. For prototyping your user interface, you need a *really rich understanding* of *your users*, of the nature of *design*, of the nature of the *technology* you're using, in order to start in a good place. Then, when you evaluate things with people,

you need to try and *really deeply* understand what's going on with them in order to actually *make things better* and possibly even to get to a point where you stand back and think: "Actually, all these little changes I'm making are not making really a sufficient difference at all. I'm going around in circles." Sometimes, you have to stand right back and make a *radical change* to your design. That's a bit like I'm climbing up a mountain

and I've suddenly realized that I've got stuck up a little peak. And I look out over there, and there's a bigger place. And I might have to go downhill and start again somewhere else. So, iteration is absolutely crucial. You won't get things right first time. You *alway*s need to iterate. So, prototyping – all sorts of prototypes, from paper prototypes to really running code – is very, very important. However, *crucial to design is having a deep and thorough understanding of your users*,

*a deep and thorough understanding of your technology and how you put them together*.

Constantly seek feedback from users and revise products accordingly. It’s impossible to understate how the continuous nature of this is vital—only when brands keep a finger on the pulse of their user base can they prevent themselves from becoming blindsided by complacency and hard-to-notice marketplace threats.

Watch as William Hudson explains some vital dimensions of user testing:

If you just focus on the evaluation activity typically with usability testing, you're actually doing *nothing* to improve the usability of your process. You are still creating bad designs. And just filtering them out is going to be fantastically wasteful in terms of the amount of effort. So, you know, if you think about it as a production line, we have that manufacturing analogy and talk about screws. If you decide that your products aren't really good enough