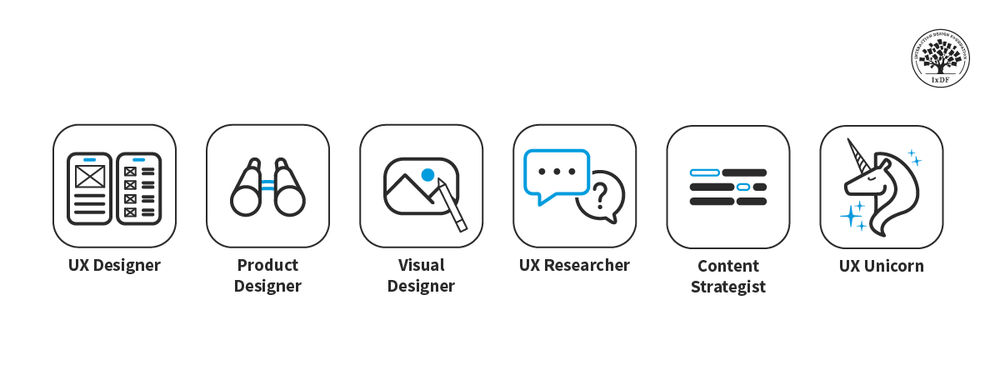

UX Roles: The Ultimate Guide – Who Does What and Which One You Should Go For?

- 1.1k shares

- 1 week ago

Product design is the process designers use to blend user needs with business goals to help brands make consistently successful products. Product designers work to optimize the user experience in the solutions they make for their users—and help their brands by making products sustainable for longer-term business needs.

“If you think good design is expensive, you should look at the cost of bad design.”

— Dr. Ralf Speth, CEO of Jaguar Land Rover

Product design is the process of creating new products that people can use. It's about solving problems and making life easier or more enjoyable through goods or services. Think of anything you use in your daily life: a phone, a chair, a video game. All these items were once just an idea that a product designer brought to life. In User Experience, Product design is about creating digital things that are easy to use, work well and look good by combining user needs with business goals.

It involves making the whole journey for users from understanding what they need to making prototypes, testing, improving, and finally launching the product. It's all about figuring out what users want and finding smart ways to give it to them.

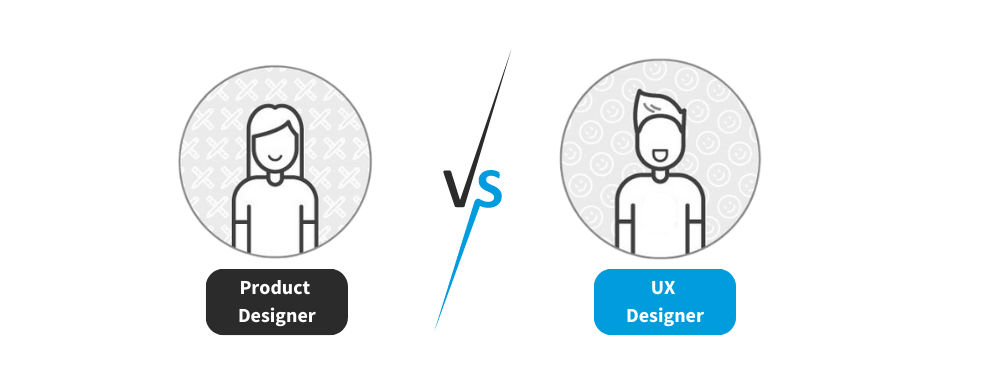

Product designers help make products which aren’t just easy and delightful (or at least satisfying) to use, but also fine-tuned to do consistently well in the marketplace. They help define product goals, create product roadmaps (high-level summaries or 6–12-month forecasts of product offerings and features) and, ideally, help brands release successful products. Much like usability and user interface (UI) design are subsets of user experience (UX) design, UX design fits within product design. Indeed, UX designers are concerned with the entire process of acquiring and integrating a product (including aspects of branding). However, product designers extend this scope to carefully monitor their brands’ positions in the market over time. They gauge likely impacts of design decisions based on in-depth domain knowledge and keep teams and organizations mindful of bigger-picture and bottom-line realities, particularly for the mid- to long term. They can therefore prevent or minimize risky consequences of implementing designs, and help maximize and sustain gains.

Throughout a project, a product designer will usually guide your design team and stakeholders on return on investment (ROI) and lower-level concerns such as the placement of interface elements. The product designer’s eye for factors such as product desirability and value is a vital safeguard to keep a brand competitive. In addition to what they would do as generalist-oriented UX designers (e.g., conducting UX research, creating personas) product designers also inform and plan roadmaps in close collaboration with development and marketing teams to ensure the feasibility of implementing designs.

Author/Copyright holder: Teo Yu Siang and the Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Product design can be demanding and intricate work. Typically, more responsibilities and specialized experience mean higher pay. As a designer and higher-level advisor, you can suggest viable alternatives to short-sighted company decisions and challenge obstacles such as the local maxima of UX. It’s important to bear in mind that the similarities between product designers and UX designers sometimes lead brands to have different definitions of the product designer’s role and the duties they expect. Some organizations may therefore fail to distinguish them from UX designers, while others may load even more responsibilities into the job description. In some instances, such as start-ups, you may find yourself acting as half the design team alongside a developer.

“Product designer” may be your dream role if you:

Enjoy developing and integrating business goals into design and product decisions;

Love participating in the entire design process;

Have deep knowledge in design and a solid understanding of business; and

Can analyze complex data to synthesize designs that satisfy business goals and user needs.

Overall, you should build brand value as you design for two overarching contexts—your users’ realities and your brand’s marketplace health—and “marry” user-centered design with market-friendly, affordable design. Your efforts in guiding the design of popular products will showcase your skills as a visionary problem-solver.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Take our UX Portfolio course to see if product design is right for you.

This post offers a wealth of insights on the differences between UX and product design.

Freelancer and e-commerce marketing specialist Leigh Kunis explores many shades of what product design involves.

Read one product design leader’s insightful take on what being a product designer means in a modern context.

Find out more about what goes into a good product roadmap.

To become a product designer, you need to have a combination of technical, creative, and interpersonal skills. Begin by understanding the complete product lifecycle, focusing on integrating beauty with functionality. As highlighted in our article, a product designer’s role is broader than a UX designer's, encompassing a range of responsibilities from concept to completion. Acquiring a solid foundation in design principles and hands-on experience is critical. Interaction Design Foundation offers many courses that can guide you in honing your design skills and techniques, setting the groundwork for a promising product design career.

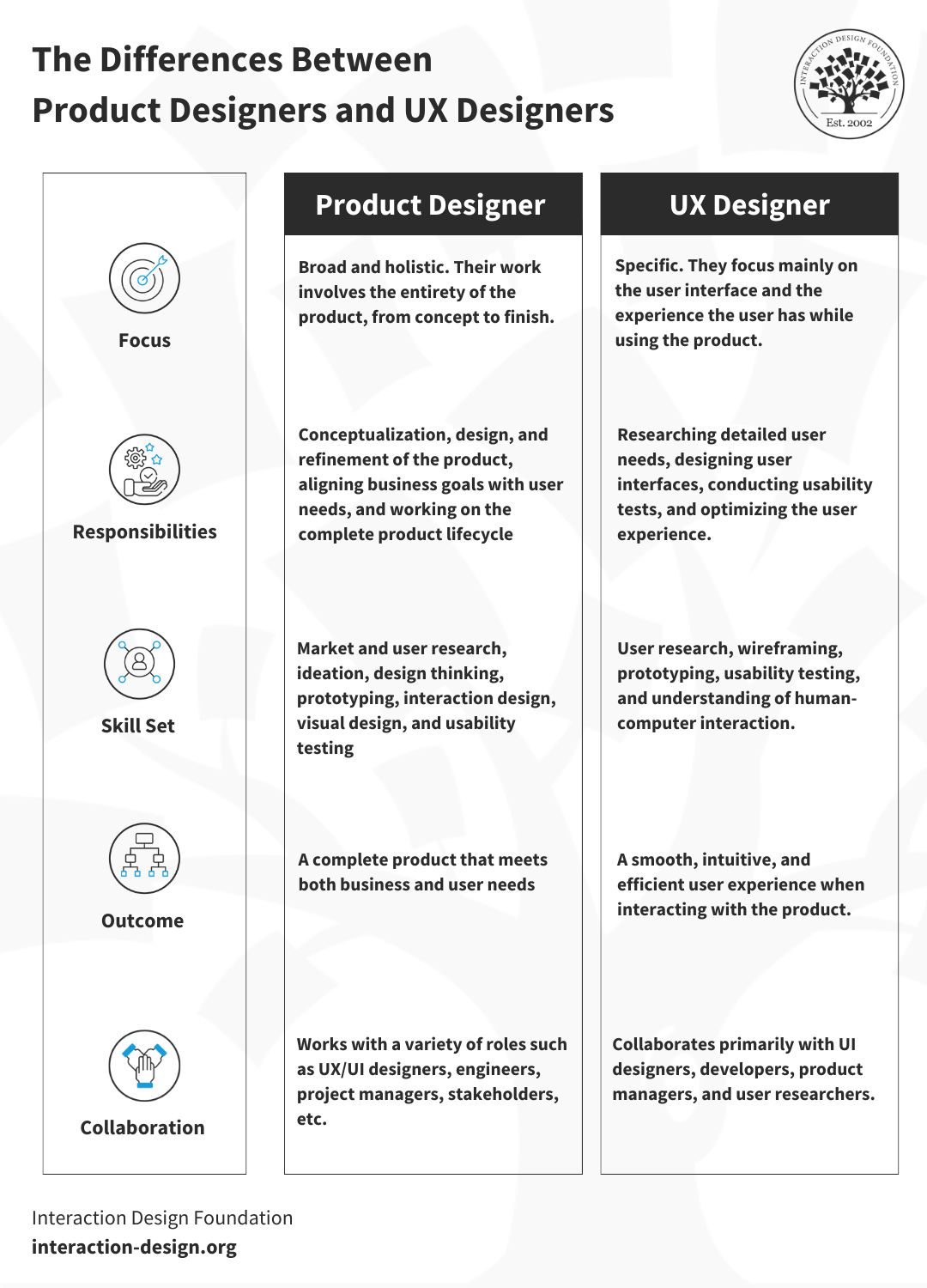

Product designers oversee the entire product lifecycle, integrating both form and function. They handle aesthetics, functionality, and user needs. On the other hand, UX designers specifically focus on user experience, ensuring products are user-friendly and meet users' needs. As outlined in the article from Interaction Design Foundation, while there's overlap, product design is broader, encompassing many aspects that UX design homes in on. For a deeper understanding, consider enrolling in Interaction Design Foundation's comprehensive courses to distinguish and master both realms.

No, product design doesn't inherently require coding. While the core focus is aesthetics, functionality, and user-centric design, knowing how to code can be beneficial. It bridges communication gaps with developers and allows for prototyping interactive elements. However, many successful product designers don't code but collaborate closely with development teams. Familiarity with technical constraints and prototyping tools can enhance design decisions, but coding isn't a prerequisite.

A product designer creates user-centric products that offer functionality and aesthetic appeal. They blend user experience (UX) principles with visual design to shape how a product looks, feels, and functions. Using research and user feedback, product designers identify pain points and craft solutions that enhance usability. Their role spans ideation, prototyping, testing, and refining designs to meet user needs and business goals. They work closely with developers, marketers, and stakeholders, ensuring the product aligns with user expectations and brand identity. While their tasks overlap with UX designers, product designers have a broader responsibility, considering the complete product lifecycle. Learn more from our detailed article on the difference between product and UX designers.

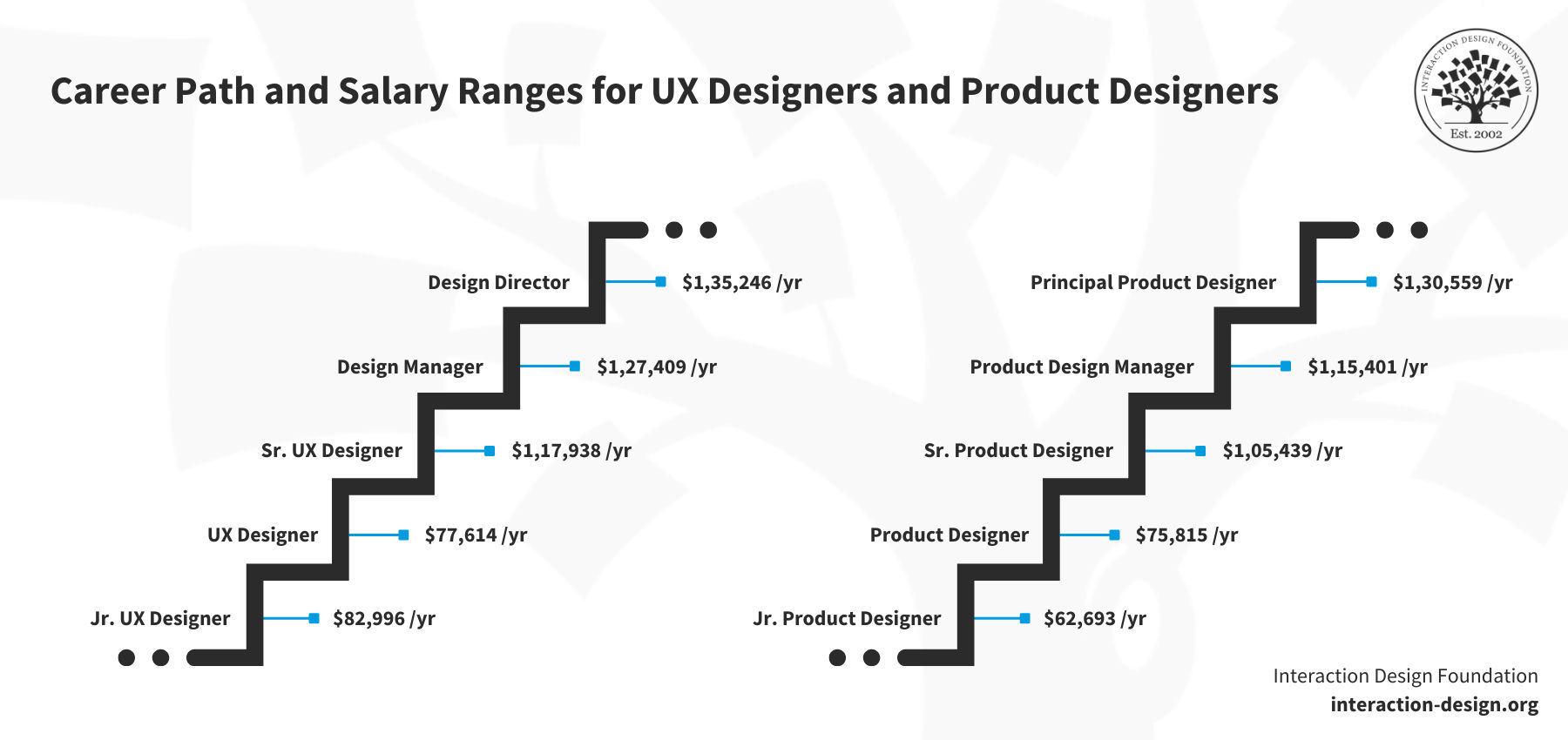

Product designers' salaries vary based on experience, location, and company size. According to Glassdoor, the national average salary for a product designer in the US is approximately $85,277 annually. However, top professionals in sought-after companies can earn significantly more. Specialized skills, portfolio quality, and industry demand can influence pay rates. Additionally, further education and courses can enhance potential and career growth. Researching and negotiating is essential based on your qualifications and the job's requirements.

Absolutely! Product design offers a dynamic and creative career path. As the Ultimate Guide to Understanding UX Roles highlights, product designers are crucial in crafting user experiences and solving real-world problems. With the digital world expanding, the demand for skilled product designers is rising. This profession provides opportunities to work in diverse industries, ensuring variety and continual learning. Moreover, it offers competitive salaries and the chance to leave a tangible impact on products many use daily. Product design is undoubtedly a rewarding career choice for those passionate about merging creativity with functionality.

Product design and product management are distinct yet collaborative roles. As discussed in our guide on becoming a product manager, product managers define a product's 'what' and 'why,' focusing on strategy, roadmap, and feature definition. They ensure the product aligns with business goals and user needs. On the other hand, product designers emphasize the 'how.' They dive deep into user experiences, crafting the product's look, feel, and functionality. While product managers set the vision and direction, product designers bring it to life through user-centered design. Both roles are vital in creating successful products, working hand-in-hand to ensure user satisfaction and business success.

Product design is a nuanced discipline that requires a blend of creativity, empathy, and technical knowledge. As our article on behavioral science in product creation highlights, understanding user behavior is pivotal. It's not just about crafting aesthetically pleasing products but ensuring they meet user needs and solve real-world problems. The process demands continuous learning, adaptability, and a user-centric approach. While some aspects may come naturally to specific individuals, achieving mastery in product design necessitates dedication, practice, and a deep understanding of design principles and human behavior. While it's a rewarding field, it's not necessarily "easy."

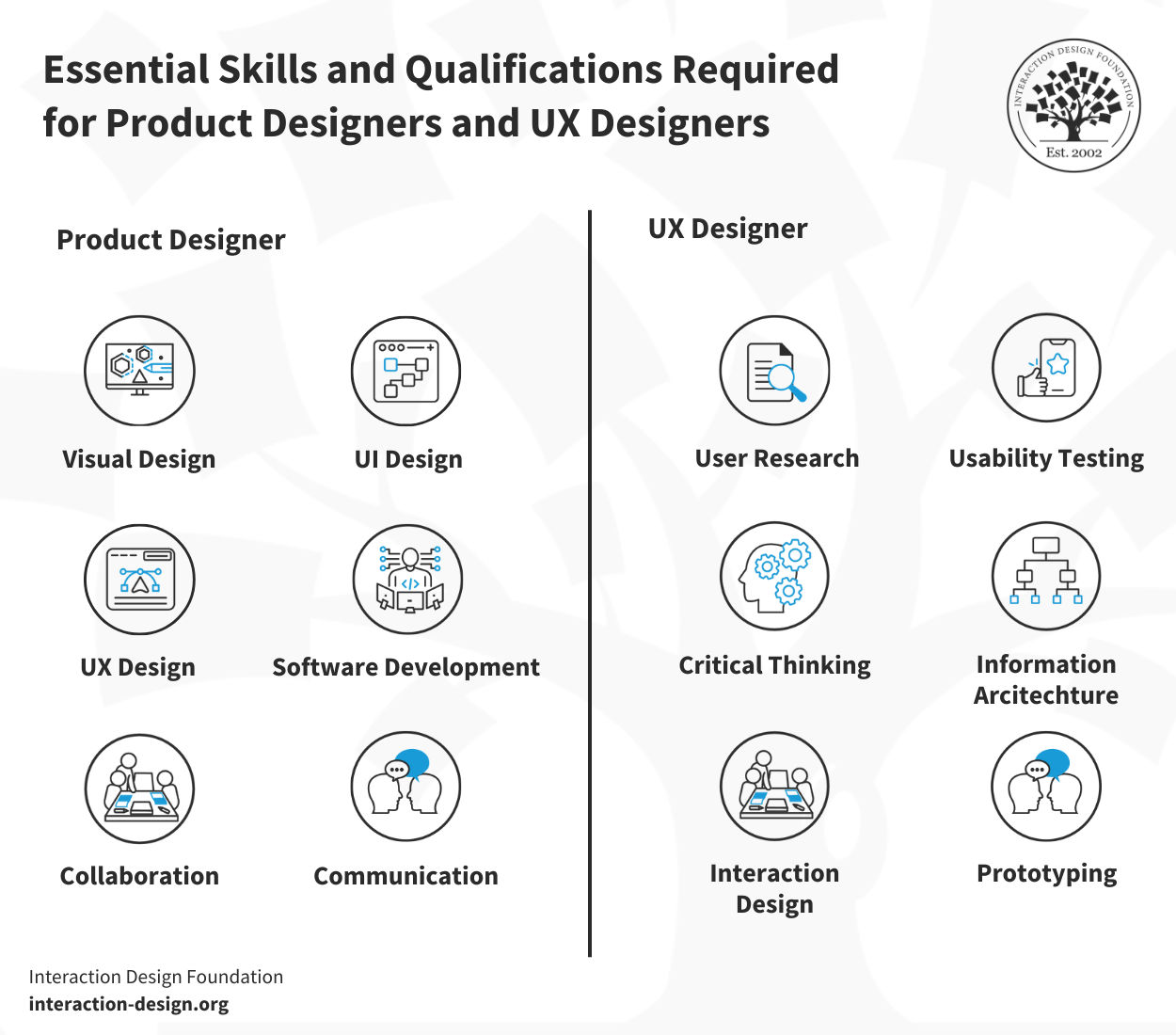

For product design, essential skills include:

Human-centered approach: Focus on understanding and designing for people's needs.

Problem-solving: Address the root cause, not just the symptoms.

Systems thinking: Recognize the complexity and interrelatedness of components in a design.

Prototyping and Iteration: Continuously refine designs based on feedback and testing.

Design research: Spend time observing and understanding the end-users.

Technical know-how: Familiarize yourself with the latest technologies and materials.

Teamwork and Collaboration: Often, product design involves collaborating with specialists from various fields.

Communication and Diplomacy: Articulate your ideas and negotiate design choices effectively with stakeholders.

Let me talk about the issues in the 21st century – the issues that are faced by designers. I've talked a lot about human-centered design, in which I've said there are four fundamental principles. One is – well, it's *human-centered*, so we focus on the people. Second, we make sure we're solving the *right problem*, not just the symptoms. Third, it's a *system* – everything is a complex system.

Things are all related to one another. And fourth, we have to learn how to prototype, test, iterate, continually modifying what we're doing to make sure it really fits the needs and capabilities of the people we're designing for. Well, let's take a look at how that plays out in design. And what I want to do is I want to talk about four examples of what designers might be doing in the 21st century.

These come from a paper that I've written. Michael Meyer, who's a professor at the University of California Design Lab and also in the business school and before that actually a very senior executive in some of the major design companies in the world. He and I have written a paper called "Changing Design Education for the 21st Century" published in a journal called "She Ji", which is published at Tongji University in Shanghai. And I happen to be a professor there.

And we said, you know, there are basically four ways of characterizing designers. That doesn't cover everything, but it shows you the broad range. And the first one is like today's designer. So, we talk about Li Na. Li Na was asked to design a new lighting system for the home market. It probably will have LEDs, so you can— first of all, they can be broad and they could be in different shapes. And, second, you can change the color of the light, and you can do all sorts of wonderful things with modern LEDs.

So, that's her design task – let's produce a whole line of products for lighting up the home. That takes advantage of all the new, exciting things that are happening in lighting devices. That's a kind of challenge that today's industrial designers are capable of solving. It requires new materials and requires new thinking and thinking in out-of-the-box ways, if you will.

But it's very traditional because the way that design education goes today is primarily one of craft – learning the skills and craftsmanship that makes for beautiful, wonderful, delightful products. And I personally believe that that education today is really superb and excellent, and I see no need to change that. So, if you wish to design beautiful products that people will love and enjoy,

fine – the traditional design education works fine. You know, for example, I happen to love this pencil. It has a wooden barrel, has a very interesting shape, and it's just delightful; it's a very simple thing. But to me, it's delightful. And I keep losing my pencils. So, what I do is I buy several at a time and so I can replace them as I lose them. And I've been through, I don't know, 10 already. And one thing I like about the wood is as I use it,

it changes its color. The oils from the finger go into the wood, and it changes the coloration. And that makes it a personalized pencil – it's *mine*. The coloration of the wood is a function of me, so – but that's traditional design: no new things, no new education is required. So, let's take a second look. Let's talk about Jin. Jin is another designer.

And Jin has been asked to design a new radiological imaging system for the medical profession. So, radiologists like to take images of inside the body. They sometimes use infrared; they sometimes use ultrasound. Sometimes, they do MRIs – magnetic resonance imaging. Sometimes they do X-rays; sometimes they do – well, there's a wide variety of imaging – imaging methods. And they like to look at it when you do an MRI, you end up with slices of the body,

and they like to look at an image at a time, and they go back and forth, back and forth across the slices, trying to understand exactly what is happening. Now, suppose you're a surgeon, and, say, the radiologist has pointed out there's a tumor. And so, your job is to remove the tumor. Well, the radiologist looks at these individual two-dimensional slices and goes back and forth, back and forth and gets a really good

feeling, and they know what's going on. That isn't how a surgeon thinks. The surgeon thinks in three dimensions. And so, a surgeon wants that very same data in a very different format. Now, take the general practitioner; the general practitioner who actually is a person who's a physician – the doctor of the patient. That person has to talk to the family, has to talk to the patient and explain what's going on. And neither the patient nor the family understands all of the technology

and all of the words, the technical terms that are used in medicine. And so, here, what the physician needs is a way of picturing – showing a picture of what is happening but in a way that everybody can understand. And there are other people helping too during the operation, and they need different images to know what's going on, so *this* is the task. So, Jin has to prepare multiple ways of presenting

the information differently for the different people who are going to use it. This requires a different kind of expertise because it's a combination of extreme knowledge of the technology and what's possible and what modern imaging and modern graphics can do. But, second, they have to be *tailored for the people* – so, the very same information has to come out in different ways. Now, Jin is usually not capable of doing the programming,

not capable of doing the technology, but *is* capable – and this is important – does understand exactly what the needs are of each of the individuals that is going to use the system. And so, it's Jin's job to bring together the technologists – all the people with the specialized knowledge, but have them make sure that what they're doing is appropriate for the people who are going to use it. Most technologists don't do that, and if you look at the fancy imaging that gets

done and the fancy graphics and displays, oh, they're very pretty, but they may not match the needs of the people who use them. So, Jin's job is to understand how to make it match and remember, there's not a single answer – the answer is different for each of the population. So, if you're given that task to do, what is it you would need to know? You would need really good skills in what we call *design research* and understanding the tasks that

each of those different people are doing or the questions that, say, the family and the patient is going to have, which means spending a lot of time observing, watching, understanding the kinds of people that you're designing for. Now, you also have to know the technology because you want to know – you might want to say, "Gee, can we present this kind of an image?" And maybe the answer is, "Well, yeah, but that's kind of a virtual reality image and they'd have to put on a helmet in order to make believe they would walk through the body.

Would that work? Actually, that might work very well for the surgeon. It might very well work for other people. It may not be the right thing, though, for the family. And it may not be the right thing for the patient. So, you're going to need a tremendous amount of modern knowledge, but, again as a generalist, you know what's possible here, what's possible here, what's possible here, and – most important of all – you know who to call upon for that knowledge

and then you have to supervise a team because they probably want to go in their own direction and you have to say, "No, no, no. We're doing this for the surgeon, and we're doing this one for the family, and we're doing this one for the general practitioner, and we're doing this one for the nurses and technical staff." And keep them focused on the different requirements that they must meet. Now,

are you *ready* to do that? You have to not only know a wide range of things, but you also have to be a good administrator, if you will, a good manager, because you'll be managing across a group of people, because radiology is a *system*. So, that's two scenarios. Now, let's look at a third one. Say, that Kim was asked to develop a whole new sanitation system for a rural town in southern India:

No electricity, no pumps, but we need a sanitation system. How would you do that? Who would you have to bring in? And remember that the kind of technology that we are used to in building systems would not be available here. And, more importantly, the people would not necessarily accept it. They wouldn't understand it. And if something went wrong, they wouldn't know how to fix it and change it. And they themselves have to do it because they're in a rural community;

they're far from the big cities; they're far from established businesses and maintenance and repair people. They take care of things themselves, so you have to build something *with them* that they can handle. And the word "with them" – don't design *for* them, because if a foreigner comes into a location – and a foreigner can be somebody from the next city; it doesn't have to be somebody from a different country –

if a foreigner comes into a location and says, "Here's what I'm going to do for you and isn't this going to be wonderful?" people don't necessarily accept that. So, we have to do a version of co-design where we're working together with the people that we're designing for to make sure that they are very happy and they've had a major say in how it should be designed. So, that's a different kind of operation, different kind of working, where the skills of the designer become more and more skills of diplomacy,

skills of getting along with a wide variety of people, maybe kinds of people you don't normally interact with, because designers, on the whole, are well educated, and now we're going to work in a group, in an area where the people are *not* well educated. And, yes, we suggested that this is a problem in southern India, and you yourself might be from southern India, but you're not from the same people that you're designing for,

because, again, you're well educated and you're from a different – you probably live in a big city with lots of facilities and these people do not. So, that's the second way. How will you address that? What would you do? So, let me go one step bigger to a fourth example. The fourth example is Erin. Erin is heading a United Nations team to address one of the major societal issues of the world.

And the United Nations has a list now of 17 major societal issues that they feel have to be addressed. And one of them is hunger. And suppose that's your task – you're going to address hunger. Well, what does that mean? What do you do? Where do you get the foods and supplies? So, you need to know about supply chains, you need to know about what's available, you need to know about transportation. You also need to know about economics. You have to have a wide range of experts helping you.

You need politicians because this is a political issue in the end. You're going to need financial people to understand the economics of doing this. You're going to need a whole bunch of engineers, and you need agricultural experts and food experts and supply chain experts because food is going to come from a variety of places. You might grow the food locally, and some might have to be imported. And to grow food, it isn't just enough to say, "We're going to grow food!"; you have to make sure that the soil is the right type; you have to make sure there's enough water;

you have to make sure there may be fertilizer and the right kinds of seeds are going to be used because food comes in many different varieties and you have to plant the thing that's appropriate for the geography and for the environment. So, in doing this, you know, Erin is really more of a *manager* than a designer. And you might even wonder, "So, what's design got to do with this?"

Well, design is an interesting discipline because we always have to bring together people from a wide variety of areas, but *remember*: What designers bring is not only the fact that we actually do things and build things, but we focus on the *people*. And we make sure we're solving the *right problem*, and we treat everything as a *system*. And we also know we don't rush to a solution and say, "Here it is!" We do a little, small test and we test it out.

And we learn from that and we modify what we're doing and we do this over and over and over again. And these four characteristics are very unique to design, and they make all the difference in the world and success. So, even though this seems like a managerial job and one that isn't at all design, it is design – and the best people in the world to do this are designers. So, there you are – four different kinds of design problems,

each of them requiring different skills and different change from the traditional design of design as a craft. But all of those are going to be critically important for the future. We don't want to lose any one of them; we want to have all four of those different things going on, which means slightly different education for those who wish to go into these areas. But you don't necessarily have to get the education at a design school. You can teach yourself. Just remember to: Think in *systems*.

Remember to always be *learning*. Remember to always be *observing*. Remember to always, *always* *focus upon the needs of the people you're designing for* – *use their creativity*. You don't have to have all the answers. Quite often the people you're designing for have the answers. They just don't know how to implement them properly. There you are – a great challenge, but that is the future of design.

Tongji University by Daniel Foster (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/danielfoster/4792534618/in/photostream/These skills align with modern challenges in product design and ensure the creation of successful, user-centric products.

To get into product design, follow these steps:

Acquire foundational knowledge in design principles.

Engage in hands-on projects to build a portfolio.

Seek mentorship from experienced product designers.

Join design communities to network and learn.

Continuously update your skills with courses like those at interaction-design.org.

Apply for internships or entry-level positions to gain real-world experience.

Remember, consistent practice and lifelong learning are key to success in product design.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Product Design by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Product Design with our course Emotional Design — How to Make Products People Will Love .

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!