Habits: Five ways to help users change them

- 654 shares

- 4 years ago

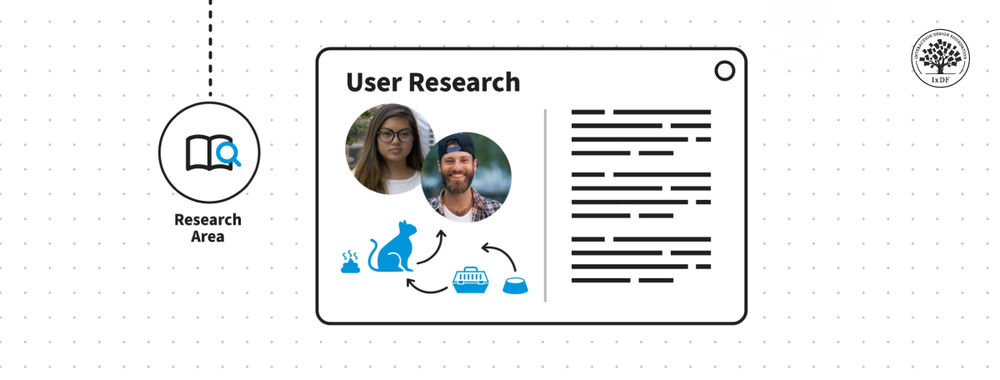

User behavior refers to users’ actions, decisions and interactions while they use a product or service. It encompasses the way users navigate through interfaces and choices they make. It includes the underlying motivations and needs that drive their behavior too. Designers must understand user behavior and get insights into user preferences, pain points and opportunities for improvement.

User experience Strategist and Consultant William Hudson explains how user research is key to understanding user behavior:

User research is a crucial part of the design process. It helps to bridge the gap between what we think users need and what users actually need. User research is a systematic process of gathering and analyzing information about the target audience or users of a product, service or system. Researchers use a variety of methods to understand users, including surveys, interviews, observational studies, usability testing, contextual inquiry, card sorting and tree testing, eye tracking

studies, A-B testing, ethnographic research and diary studies. By doing user research from the start, we get a much better product, a product that is useful and sells better. In the product development cycle, at each stage, you’ll different answers from user research. Let's go through the main points. What should we build? Before you even begin to design you need to validate your product idea. Will my users need this? Will they want to use it? If not this, what else should we build?

To answer these basic questions, you need to understand your users everyday lives, their motivations, habits, and environment. That way your design a product relevant to them. The best methods for this stage are qualitative interviews and observations. Your visit users at their homes at work, wherever you plan for them to use your product. Sometimes this stage reveals opportunities no one in the design team would ever have imagined. How should we build this further in the design process?

You will test the usability of your design. Is it easy to use and what can you do to improve it? Is it intuitive or do people struggle to achieve basic tasks? At this stage you'll get to observe people using your product, even if it is still a crude prototype. Start doing this early so your users don't get distracted by the esthetics. Focus on functionality and usability. Did we succeed? Finally, after the product is released, you can evaluate the impact of the design.

How much does it improve the efficiency of your users work? How well does the product sell? Do people like to use it? As you can see, user research is something that design teams must do all the time to create useful, usable and delightful products.

User behavior is a fundamental aspect of user experience (UX) design—at the very heart of the craft, in fact. As a concept, it spans the way users actually interact with a product, the decisions they make—and the actions they take. And when designers analyze user behavior, they get valuable insights that can inform the design process exceedingly well. From there, designers can improve the usability of a product or service—and much more.

It’s a vital point that designers really understand what influences user behavior—so they can create intuitive and user-friendly designs. A wide range of factors influence users’ behaviors—and these include internal and external factors—such as the following:

Internal factors inherently link to a user's psychological state. They encompass:

1. Motivations: Crucially, designers must understand what motivates users to interact with a product or service. Whether it's to achieve a goal, satisfy a need or just seek pleasure, these motivations are very important for designers to unearth—to create experiences that resonate with individual users.

2. Cognitive biases: Cognitive biases are mental shortcuts—ones that people use to make decisions quickly. Designers can leverage these biases to make more effective experiences and prompt users to engage. For example, there’s the anchoring bias—that’s one where users rely heavily on the first piece of information they receive.

Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains bias and anchoring:

We have tendencies to see things in one way or another. And that's about all sorts of things. That can be about serious personal issues; it can be about trivial things. Often the way in which *something is framed to us can actually create a bias* as well. A classic example, and there are various ways you can do this, is what's called *anchoring*. So, if we're asked something and given something that *suggests a value*,

even if it's told that it's just there for guesswork purposes or something, it tends to hold us and move where we see our estimate. So, you ask somebody, "How high is the Eiffel Tower?" You might have a vague idea that it's big, but you probably don't know exactly how high. You might ask one set of people and give them a scale and say, "Put it on this scale; just draw a cross where you think on this scale from 250 meters high to 2,500 meters high.

How high on that scale?" And people put crosses on the scale – you can see where they were, or put a number. But alternatively, you might give people – instead of having a scale of 250 meters to 2,500 meters, you might give them a scale between 50 meters and 500 meters. Now, actually, the Eiffel Tower falls on *both* of those scales; the actual height is around 300 meters. But what you find is people don't know the answer; given the larger, higher scale, they will tend to put something that is larger and higher,

even though they're told it's just a scale. And actually, on the larger scale, it should be right at the bottom. Here, it should be about two-thirds of the way up the scale. But what happens is you, by framing it with big numbers, people tend to guess a bigger number. If you frame it with smaller numbers, people guess a smaller number. They're anchored by the nature of the way the question is posed. So, how might you get away from some of this fixation? We'll talk about some other things later,

other ways later. But one of the ways to actually *break* some of this bias and this fixation is to *deliberately mix things up*. So, what you might do is, say, you're given the problem of *building* the Eiffel Tower. And the Eiffel Tower I said is about 300 meters tall, so about 1,000 feet tall. So, you might think, "Oh crumbs, how are we going to build this?" So, one thing you might do is say, "Imagine instead of being

300 meters tall, it was just 3 meters tall. How would I go about building it, then?" And you might think, "Well, I'd build a big, perhaps a scaffolding, or 30 meters tall – I might build a scaffolding and just hoist things up to the top." So, then you say, "Well, OK, can I build a scaffolding at 300 meters; does that make sense?" Alternatively, you might say, "Perhaps it's 300,000 *miles* tall, basically reaching as high as the Moon. How might I build it, then?" Well, there's no way you're going to hoist things up a scaffold.

All the workers at the top would have no oxygen because they'd be up above the atmosphere. So, you might then think about hoisting it up from the bottom, building the top first, hoisting the whole thing up; building the next layer; hoisting the whole thing up; building the next layer – you know – like jacking a car and then sticking bits underneath. So, by just thinking of a *completely different* scale, you start to think of different kinds of solutions. It forces you out of that fixation. You might just swap things around. I mean, this works quite well if you're worried

that you're using some sort of racial or gender bias; you just swap the genders of the people involved in the story or swap their ethnic background, and often the way you look at the story differently might tell you something about some of the biases you bring to it. In politics, if you hear a statement from a politician and you either react positively or negatively to it, it might be worth just thinking what you'd imagine if that statement

came from the mouth of another politician, that was of a different persuasion; how would you read it then? And it's not that you change your views drastically by doing this, but it helps you to perhaps expose why you view these things differently. And some of that might be valid reasons; sometimes, you might think, "Actually, I need to rethink some of the ways I'm working."

3. Emotions: Emotions have a massive bearing on how users interact with products and services. Positive emotions, of course, boost user engagement. Meanwhile, negative emotions can—but don’t always—lead to user dissatisfaction and churn.

4. Perceptions: Perception is the way that users interpret—and understand—the world around them. And factors like color, typography and imagery can have a massive impact on user perception—and so influence how users interact with an interface.

5. Past experiences: Users bring their past experiences and knowledge with them to each interaction. Previous encounters with similar products—or services—can shape their expectations and behaviors. Designers can work with these prior experiences to make intuitive and familiar interactions.

External factors are those elements outside the user's individual psyche that can influence their behavior. They’re items like the environment, context, culture and social factors.

1. Environment: The physical environment can greatly influence a user’s behavior. And it could include lighting, noise levels—and even the device the user uses. Designers really need to consider these factors if they’re to create experiences that suit various environments.

2. Context: The context in which a user uses a product or service can have a big bearing on their behavior. And this could include the time of day, the user's location or even how they’re feeling emotionally. Designers need to gain sharp insights into the many contexts that users across a product’s or service’s user base will find themselves in at various times.

Professor Alan Dix explains how important it is for designers to work with the users’ context in mind:

3. Culture: Cultural norms, values and expectations can shape user behavior. Designers have got to be mindful of cultural nuances if they’re to create designs that are both respectful and inclusive.

4. Social factors: Social influences can also impact user behavior. They’re items such as peer pressure and societal trends. And if designers include social proof elements like testimonials or user reviews in their design work, they can encourage specific user behaviors.

Adagio Teas leverages reviews to influence prospective buyers.

© Jen Cardello / via Adagio Teas, Fair Use

UX designers face a wide range of challenges from user behavior. They’ve got to deal with diverse user expectations and grapple with cognitive biases, for example. These challenges call for designers to be skilled enough to understand—and predict—user behavior. Here are some common issues:

User behavior is inherently complex and dynamic. And it can vary across different individuals and change over time. No matter what the target audience may be, users do come from diverse backgrounds—and have different expectations, preferences and needs, too. It can be a challenge for designers to cater to this diversity and make sure that inclusivity figures strongly in design. Designers have got to think about this complexity whenever they design user experiences—to make sure they actually do meet users’ diverse needs and preferences.

User behavior is subjective—and it’s something that can vary from person to person. Designers have got to account for this subjectivity and variability when they conduct user research. And, after designers collect feedback, they work these user insights into their design process—to help them create experiences that resonate with a broad range of users.

Professor Alan Dix explains the difference between the two main types of user research, qualitative and quantitative research.

Ah, well – it's a lovely day here in Tiree. I'm looking out the window again. But how do we know it's a lovely day? Well, I could – I won't turn the camera around to show you, because I'll probably never get it pointing back again. But I can tell you the Sun's shining. It's a blue sky. I could go and measure the temperature. It's probably not that warm, because it's not early in the year. But there's a number of metrics or measures I could use. Or perhaps I should go out and talk to people and see if there's people sitting out and saying how lovely it is

or if they're all huddled inside. Now, for me, this sunny day seems like a good day. But last week, it was the Tiree Wave Classic. And there were people windsurfing. The best day for them was not a sunny day. It was actually quite a dull day, quite a cold day. But it was the day with the best wind. They didn't care about the Sun; they cared about the wind. So, if I'd asked them, I might have gotten a very different answer than if I'd asked a different visitor to the island

or if you'd asked me about it. And it can be almost a conflict between people within HCI. It's between those who are more *quantitative*. So, when I was talking about the sunny day, I could go and measure the temperature. I could measure the wind speed if I was a surfer – a whole lot of *numbers* about it – as opposed to those who want to take a more *qualitative* approach. So, instead of measuring the temperature, those are the people who'd want to talk to people to find out more about what *it means* to be a good day.

And we could do the same for an interface. I can look at a phone and say, "Okay, how long did it take me to make a phone call?" Or I could ask somebody whether they're happy with it: What does the phone make them feel about? – different kinds of questions to ask. Also, you might ask those questions – and you can ask this in both a qualitative and quantitative way – in a sealed setting. You might take somebody into a room, give them perhaps a new interface to play with. You might – so, take the computer, give them a set of tasks to do and see how long they take to do it. Or what you might do is go out and watch

people in their real lives using some piece of – it might be existing software; it might be new software, or just actually observing how they do things. There's a bit of overlap here – I should have mentioned at the beginning – between *evaluation techniques* and *empirical studies*. And you might do empirical studies very, very early on. And they share a lot of features with evaluation. They're much more likely to be wild studies. And there are advantages to each. In a laboratory situation, when you've brought people in,

you can control what they're doing, you can guide them in particular ways. However, that tends to make it both more – shall we say – *robust* that you know what's going on but less about the real situation. In the real world, it's what people often call "ecologically valid" – it's about what they *really* are up to. But it is much less controlled, harder to measure – all sorts of things. Very often – I mean, it's rare or it's rarer to find more quantitative in-the-wild studies, but you can find both.

You can both go out and perhaps do a measure of people outside. You might – you know – well, go out on a sunny day and see how many people are smiling. Count the number of smiling people each day and use that as your measure – a very quantitative measure that's in the wild. More often, you might in the wild just go and ask people. It's a more qualitative thing. Similarly, in the lab, you might do a quantitative thing – some sort of measurement – or you might ask something more qualitative – more open-ended. Particularly quantitative and qualitative methods,

which are often seen as very, very different, and people will tend to focus on one *or* the other. *Personally*, I find that they fit together. *Quantitative* methods tend to tell me whether something happens and how common it is to happen, whether it's something I actually expect to see in practice commonly. *Qualitative* methods – the ones which are more about asking people open-ended questions – either to both tell me *new* things that I didn't think about before,

but also give me the *why* answers if I'm trying to understand *why* it is I'm seeing a phenomenon. So, the quantitative things – the measurements – say, "Yeah, there's something happening. People are finding this feature difficult." The qualitative thing helps me understand what it is about it that's difficult and helps me to solve it. So, I find they give you *complementary things* – they work together. The other thing you have to think about when choosing methods is about *what's appropriate for the particular situation*. And these things don't always work.

Sometimes, you can't do an in-the-wild experiment. If it's about, for instance, systems for people in outer space, you're going to have to do it in a laboratory. You're not going to go up there and experiment while people are flying around the planet. So, sometimes you can't do one thing or the other. It doesn't make sense. Similarly, with users – if you're designing something for chief executives of Fortune 100 companies, you're not going to get 20 of them in a room and do a user study with them.

That's not practical. So, you have to understand what's practical, what's reasonable and choose your methods accordingly.

Designers have got to strike a balance between how they meet user needs and how they achieve business goals, too. And, while it’s essential for them to prioritize user satisfaction, they’ve also got to consider the business objectives and constraints. This takes careful consideration—and trade-offs—during the design process. Non-design stakeholders, marketing campaign personnel and others sometimes can’t see eye to eye with designers, product managers and other product team members.

Emotions have a huge influence on user behavior—naturally—but it can be tricky to design for emotions. For designers to strike the right emotional chord, they’ve got to build up a deep understanding of users—and a delicate balance of design elements.

User behavior isn’t static. It’s something that can change over time. So, designers need to anticipate—and adapt—to these changes. They’ve got to continuously monitor user behavior, collect feedback and iteratively improve the user experience. Designers have to stay agile—and responsive—to evolving user needs and users’ problems. That’s crucial for them to design successful products.

Cognitive biases can lead users to behave irrationally or make poor decisions, and biases—such as confirmation bias—tend to be universal. They’re one of the greatest challenges in UX design—something of an “occupational hazard” of being human. Designers have got to be exceptionally mindful of these biases—and create interfaces that mitigate their effect.

Designers face the challenge of being mindful of their own bias, too, when they commit to designing for users. CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers explains an essential aspect of this bias in the following video:

For you, one of your biggest biases and issues as a designer if you're a visual designer or if you're working on a website or app that – you know – you're a stakeholder on the team, it's going to be the fact that you can actually see what's on a screen, assuming that you're not blind, that you're actually reviewing visual designs.

And the things that I found that are the biggest challenges for visual design are the *semantics*. So, words make sense when you look at them or descriptions are aided with a visual cue; you know – confirmation messages visually colored or it flashes up and there's something that gives you a visual cue there, error messages the same thing. So, these kind of semantics of – you know –

that you understood an error message or you understood something are one of the things we just get used to. And then we forget what it might be like if you don't have the visual crutch. So, this example here is a quiz, and this is where we saw this, when we were optimizing this quiz, that when we were looking at the accessibility of it, the problem with it – so we went through and we made it accessible, so you could

keyboard and tab through the the different choices – and then we tested it with a user. And we were like, oh – we totally didn't realize this. What was happening is that the correct answer was appearing to the left of the answer choice. And the problem was that when it announced the correct choice, even though it was accessible, it didn't say which one it was.

So, say Choice B was circled and then the correct answer was displayed over there, but it just didn't have this semantic of saying, "The correct answer is Choice B (blah blah blah blah blah)." So, very simple, but a good reminder of like, oh yeah – you know – reinforcing the fact that your visual bias adds context; that might not be there when it's read aloud or when it's navigated through an audible experience like a screen reader.

The second bucket for visual bias is the interaction; it's the little animations or little micro-interactions that are occurring on a screen are another source of – you know – it's like, "Well, I saw that, but a screen reader didn't." You know. So, being aware of that, as well as the third one, which is *place*. So, like the location on a screen or movement that occurs – some meaning from a state change.

Like a hover is a classic one – you hover on and off and it kind of tells you that it's a clickable element or it tells you that nothing's happening. Sometimes you click on stuff, play buttons or you click on elements on a screen that are loading like a button or something like that – nothing happens. And then you can kind of tell nothing's happening because if you have a little technical proficiency as a user, you can look down and see if the page is loading on your browser in the lower-left corner

or you can see that nothing happened – you push the button and nothing happens. Well, if you don't have that visual cue or if something is placed in an area of a screen that you have to kind of navigate back up to the top if you're using assistive technology, that's going to be a blocker. Right? So, visual bias I think is our worst enemy because we're so familiar with it, we're so used to it that we've forgotten that we are, so we have that crutch.

There's more than one bias, though. There's *mouse-heavy bias*. So, we've gotten used to the fact that we use mice all the time and as designers we require point and click a lot. So, it took me a while to realize how important this was. Many years ago when I was doing lots of usability – you know – kind of user studies and going out and talking to users, then when you're doing B2B studies (business-to-business studies), you usually run across

that one user who is the keyboard user, and it's like "I don't use the mouse." Like, this woman is using this very important software for the company and sometimes she's the only user. And she's going through and just because of the speed that she needs to input, it's keyboard-driven. Now, we found this with many types of applications like that, so designing for keyboard accessibility for the heavy input user is just something that you end up supporting.

It's one of these universal type of design approaches. And so, with accessibility, we're blocking users if we make things too mouse-dominant because then they're not able to use the keyboard. And without the keyboard, there's usually not a focus state related to that. So, we'll talk more about focus states just like we've been talking about since they're so important. Now, the other bias is the *color bias* – so we've talked about color blindness.

And for example, putting error messages only in red text. And if you recall the guideline there is to add a supporting element like another visual element to reinforce the color. Don't just use color alone basically. So, watch out for those three biases: *visual bias, color bias and mouse bias* because as a sighted designer or business person or developer you're probably

going to be biased by those things. Now, in the design phase, some of the very basic accessibility things you should be nipping in the bud, in other words, stopping them before the train goes down the track are things like *typography*, so the size of your font; designing and defining that up front or making sure that that's documented in a style guide is really important. If it's not, then that's where a developer needs to be familiar with accessibility so they can stop it

at their stage of coding or a front-end web developer who's putting together a style sheet that will call those styles. So, *color contrast* is the other big classic, and I think if there's one skill that any good designer – and I'm talking visual designer – needs to learn, it's *high contrast* because that seems to be the big one from the dozens of designers that I've worked with over the years. It seems like they give me designs all the time that are low contrast. It's the gray on gray, as I like to joke.

Then *link visibility and target size* is the other one. This is all up front. So, before you even get to thinking about accessibility, you should be thinking about that. And then *labeling or label proximity* – so how close the label is to the element that you're trying to get the call to action on. Once you have those basics, then you can add *predictability and consistent navigation*;

things like the focus, focusability, and then the blocks of content being separated and distinct from each other.

User behavior can present challenges and problems for designers—and some common examples include:

Users often abandon their shopping carts before they actually go through with completing a purchase—and it’s something that several factors can influence. These include unexpected costs, complex checkout processes or a lack of trust in the website's security. So, designers should streamline the checkout process, provide clear pricing information—and build trust. They can boost their users’ trust a great deal through secure payment options and customer reviews.

Low user engagement is a common challenge that designers have. Users may visit a website or app—but fail totally to engage further with its content or features. That sort of behavior can come from factors like unclear navigation, uninteresting content or a lack of personalization. So, designers really need to work to create intuitive navigation and compelling content. They’ve got to make personalized experiences that resonate with users' interests and preferences, too.

High bounce rates happen when users leave a website or app—and quickly—after they’ve viewed only one page. Factors such as slow loading times, irrelevant content or poor usability can help bring about and influence this behavior. To address this, designers should optimize website performance—and provide relevant and engaging content; plus, they need to make sure there’s a seamless user experience, too.

Users may struggle to complete tasks efficiently—and that can be due to confusing interfaces, complex workflows or a lack of clear instructions. Users can end up feeling frustrated and leave with a bad impression of the brand—never to return. So, it’s all the more imperative that designers conduct proper user research, simplify interfaces, provide clear instructions and optimize workflows—to help users complete tasks more efficiently.

CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers explains the importance of task analysis:

So, task analysis is an extremely important technique. And, to be clear, you can do your task analysis when you do your regular user research and interview observation; that's the observation side. That's where you ask a user, "Hey can you show me how you do it today?" Now, don't worry about the technology; don't worry about any tools they may be using

– you know – existing applications or whatever. Just have them go through what they normally do. It's even great in task analysis to see things in the absence of some technology like your design or whatever. So, if they want to show you how they normally do it, then you'll get to see their kind of workarounds, their patterns, their shadow spreadsheets – you know – ways of coping, their hacks and their adjustments, things they've done to make it work.

And that stuff is just beautiful. But having them step through their problem solving step by step, kind of 'teach me how you do it' – that's the basis of task analysis. If you're doing *ethnography*, which is similar to interview observation – you're essentially looking for a few more cultural cues with ethnography; you're looking for things of cultural significance, and it might just be user culture. It might be in that region of the country you're learning about the users.

Or it might be at a national level or international level if you're doing localization or cross-cultural research. It might even be the culture of an underrepresented group if you're doing inclusive research and inclusive design, trying to understand the experience of that community, their history, their lived experience as it relates to the problem they're trying to solve or how they approach it. So, task analysis is definitely one of these things that you want to build into your tool set.

And essentially what you're going to do is take those observations from your research and you're going to map them out and kind of flow chart them, flow diagram them and see how you can take that structure and map it to your design kind of like as the user goes from here to here to here, how can my screen support this thing that they do here with this tool or this feature? Kind of see how you can make it flow much more intuitively

so it feels good and makes sense to your users.

UX researchers and designers leverage user behavior analytics (UBA). UBA calls for them to collect data and analyze it to gain insights into user behavior. This data-driven approach provides valuable information that can inform design decisions and improve the user experience. Google Analytics, for instance, provides excellent insights. Some popular tools and techniques for user behavior analytics include:

Clickstream analysis tracks the sequence of user interactions on a website or app. It’s important as it gives insights into user navigation patterns, popular pages and drop-off points. And designers can use this information—to optimize navigation, improve the content placement and give the user journey needed boosts.

Conversion funnel analysis tracks user behavior—throughout the conversion process—going from initial interaction to desired action. It helps to find areas of friction, drop-off points and chances for optimization. Designers can use this analysis to streamline the conversion process and so improve conversion rates.

A/B testing calls for designers—or user researchers—to compare two or more variations of a design to see which performs better in terms of user behavior and desired outcomes. It’s a helpful way to test different design elements, content or user flows—so that designers and design teams can make solid data-informed decisions.

Heatmaps visually represent user behavior patterns—and they highlight areas of a website or app that get the most attention or interaction. This information can help designers find areas of interest, user preferences—and potential usability issues.

Heatmaps show users’ viewing behavior in a well-defined way.

© Adam Kiss, Fair Use

Design professionals have applied UBA in various industries and contexts—and done so to improve user experiences. The interplay between user behavior and UX design is easy to understand—through real-world examples and case studies—and here are a few instances where user behavior has impacted UX design:

Netflix analyzes user behavior data to provide personalized movie and TV show recommendations. And when they track user viewing history, ratings and interactions, Netflix can suggest content that aligns with users' preferences—and this increases engagement and satisfaction.

Many data points on customers greatly enhance customer recommendations, lower churn rate and ensure customer loyalty.

© Rebuy Engine, Fair Use

Amazon uses user behavior analytics to implement dynamic pricing strategies. When Amazon analyzes factors such as user browsing history, purchase behavior and market trends, they can optimize prices in real-time. Plus, they can offer personalized and competitive pricing to users, too.

Amazon's one-click ordering feature is another solid example of designing for user behavior. Amazon understood well that users value speed and convenience. So, they created a feature that drastically simplified the checkout process—and led to increased conversions.

Instagram introduced the “double tap” as a new behavior for liking posts. This innovative feature quickly gained a great deal of popularity due to its ease and intuitiveness. And it demonstrates the power of how a brand can understand and influence user behavior in user experience design.

Spotify leverages user behavior data to create personalized playlists—and this feature is something that creates a highly engaging and personalized user experience. This use of user behavior analytics really highlights the potential of data-driven design.

Spotify’s personalized playlists offer customized ways to delight users according to their tastes.

©Spotify, Fair Use

Designers should bear in mind that it’s an ongoing process to account for user behavior—one that calls for continuous research, testing and iteration. Here are some practical tips—and best practices—to address user behavior:

Designers need to understand their target audience—thoroughly—through UX research. This includes surveys, interviews and usability testing. It’s vital to get good insights into users’ behaviors, needs and pain points to inform design decisions properly.

Designers should develop user personas—which they base on research—to represent different user groups. Personas help designers empathize with users and design experiences that truly meet their specific needs and preferences.

Personas help bring the realities of a target audience closer, so the design team can iterate the best solutions.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

User journey maps visualize the entire user experience—and they highlight touchpoints, emotions and interactions. These maps can help designers to identify pain points and really optimize the UX.

Designers should create intuitive user flows—ones that guide users through tasks and processes smoothly. It’s essential to minimize friction points, streamline interactions and provide clear instructions—and so make the most of user efficiency.

User flows help designers realize vital areas and dimensions of what users experience as they go from point to point—towards a desired goal.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Designers should continuously test and iterate on designs based on the user feedback and behavior data they get in. And they should use A/B testing, usability testing and analytics tools to collect insights and make data-informed design decisions.

Designers should apply principles of behavioral psychology—such as cognitive biases and heuristics—to nudge users towards desired actions—and ethically so. It’s vital to design experiences that align with users' mental models and leverage their cognitive biases to make good decision-making easier for them.

Designers should offer clear feedback and guidance to users throughout their interactions. And it’s important to inform users of the consequences of their actions, provide error messages that guide them towards resolution—and offer helpful suggestions for improvement.

Google offers feedback to help users stay on track with what they want to do.

© Google, Fair Use

Designers should use user behavior data to help them personalize both experiences and content. They should tailor recommendations, notifications and interactions based on users' preferences and past behaviors. It’s something that can help designers to create experiences that are highly engaging and relevant.

It’s essential to continuously monitor and analyze user behavior with the use of analytics tools. Designers have got to get insights into user interactions, engagement patterns and pain points if they’re to identify areas for improvement and inform future design decisions well. User behavior analytics tools provide quantitative data about user interactions—and they give actionable insights that can guide design decisions very well.

UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains when and why to use user analytics:

*When and Why to use Analytics* Primarily, we're going to need to be using analytics on existing solutions. So, if you're talking about *green field* – which is a brand-new solution, hasn't been built and delivered yet – versus *brown field* – which is something that's already running but perhaps we want to improve it – then we're decidedly on the brown field side.

So, we're looking at existing solutions because it's only existing solutions that can provide us with the analytics. If you haven't got an existing solution, you're going to have to use another technique. And there are obviously many other techniques, but they're not going to provide you with much in the way of *quantitative data*. We do have early-research methods, which we'll be talking about very briefly as an alternative, but predominantly analytics for existing deployed solutions.

Having said that, then if you're looking at a rework of an existing site or app, then looking at current analytics can tell you a lot about what you might like to address; what questions you might like to raise with your team members, stakeholders, users. So, those are important considerations. A good starting point in organizations or teams with low UX maturity is analytics because analytics are easier to sell – to be honest – than qualitative methods.

If you're new to an organization, if they're only just getting into user experience, then trying to persuade colleagues that they should be making important decisions on the basis of six to eight qualitative sessions, which is typically what we do in the usability lab, then you should find by comparison web analytics a much easier thing to persuade people with. And the other issue particularly relevant to qualitative methods

is that quantitative methods tend to be very, very much cheaper – certainly on the scale of data, you are often having to talk in terms of hundreds of dollars or pounds per participant in a *qualitative* study, for various expenses; whereas a hundred dollars or pounds will get you potentially hundreds or thousands of users. And, in fact, if you're talking about platforms like Google Analytics which are free, there is no cost other than the cost of understanding and using

the statistics that you get out; so, obviously it is very attractive from a cost perspective. Some of the things that we'll be needing to talk about as alternatives to analytics or indeed *in addition* to analytics: Analytics can often *highlight* areas that we might need to investigate, and we would then have to go and consider what alternatives we might use to get to the bottom of that particular problem.

Obviously, *usability testing* because you'll need to establish *why* users are doing what they're doing. You can't know from analytics what users' motivations are. All you can know is that they went to *this* page and then they went to *that* page. So, the way to find out if it isn't obvious when you look at the pages – like there's something wrong or broken or the text makes no sense – is to bring users in and watch them actually doing it, or even use remote sessions – watching users doing the thing that has

come up as a big surprise in your analytics data. A/B testing is another relatively low-cost approach. It's – again – a *quantitative* one, so we're talking about numbers here. And A/B testing, sometimes called *multivariate testing*, is also performed using Google Tools often, but many, many other tools are available as well; and you show users different designs;

and you get statistics on how people behaved and how many converted, for example. And you can then decide "Well, yes, putting that text there with this picture over here is better than the other way around." People do get carried away with this, though; you can do this ad nauseam, to the point where you're starting to change the background color by minute shades to work out which gets you the best result. These kinds of results tend to be fairly temporary. You get a glitch and then things just settle down afterwards.

So, mostly in user experience we're interested in things which actually really change the user experience rather than getting you temporary blips in the analytics results. And then, finally, *contextual inquiry* and *early-design testing*: Contextual inquiry is going out and doing research in the field – so, with real users doing real things to try to find out how they operate in this particular problem domain; what's important to them; what frustrations they have;

how they expect a solution to be able to help them. And early-design testing – mostly in the web field these days but can also be done with software and mobile apps; approaches like *tree testing* which simulate a menu hierarchy. And you don't actually have to do anything other than put your menu hierarchy into a spreadsheet and upload it – it's as simple as that; and then give users tasks and see how they get on.

And you can get some very interesting and useful results from tree testing. And another early-design testing approach is *first-click testing*. So, you ask users to do something and you show them a screenshot – it doesn't have to be of an existing site; it can be just a design that you're considering – and find out where they click, and is where they click helpful to them? Or to you? So, these are examples of early-design testing – things that you can do *before* you start building

a product to work out what the product should look like or what the general shape or terminology or concepts in the product should be. And both of these can be used to find out whether you're on the right track. I have actually tested solutions for customers where users had no idea what the proposition was: "What does this site do?"; "What are they actually trying to sell me?" or "What is the purpose of it?" – and it's a bit late to be finding that out in usability testing towards the end of a project, I have to say. And that was indeed exactly what happened in this particular example

I'm thinking of. So, doing some of these things really early on is very important and, of course, is totally the opposite of trying to use web analytics, which can only be done when you finish. So, do bear in mind that you do need some of these approaches to be sure that you're heading in the right direction *long before* you start building web pages or mobile app screens. Understand your organization's *goals* for the interactive solution that you're building.

Make sure that you know what they're trying to get out of it. Speak to stakeholders – stakeholders are people typically within your organization who have a vested interest in your projects. So, find out what it's supposed to be doing; find out why they're rebuilding this site or why this mobile app is being substantially rewritten. You need to know that; so, don't just jump in and start looking for interesting numbers.

It's not necessarily going to be that useful. Do know the solutions; become familiar with them. Find out how easy it is to use them for the kinds of things which your stakeholders or others have told you are important. Understand how important journeys through the app or website work. And get familiar with the URLs – that's, I'm afraid, something that you're going to be seeing a lot of in analytics reports – the references for the individual pages or screens,

and so that you'll understand, when you actually start looking at reports of user journeys, what that actually means – "What do all these URLs mean in my actual product?" So, you're going to have to do some homework on that front. You're also going to have to know the users – you need to speak to the users; find out what they think is good and bad about your solutions; find out how they think about this problem domain and how it differs from others and what kind of solutions they know work and what kind of problems they have with typical solutions.

Also ask stakeholders and colleagues about known issues and aspirations for current solutions. So, you know, if you're in the process of rebuilding a site or an app, *why* – is it just slow-ish? Is it just the wrong technology? Maybe. Or are there things which were causing real problems in the previous or current version and that you're hoping to address those in the rebuild.

It’s crucial to ensure that the product’s accessible and usable for all users. And this means that designers must design for different devices, incorporate accessibility features and make sure there’s easy navigation—no matter who’s using the digital solution.

Usability and accessibility are vital parts of the 7 key factors of UX.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

When UX designers fail to properly address user behavior in digital products and services, several problems can rear their heads. And they’re things that can potentially lead to a product's underperformance—or even total failure—in the marketplace:

Inadequate engagement: If the product doesn’t align with user expectations or behaviors, users mightn’t find it engaging or intuitive—and it'll lead to low adoption rates.

High user churn: Users may abandon the product quickly after the initial trial if it doesn’t cater to their needs or behaviors.

Frustration: Users may end up feeling frustrated if the product is hard to navigate or doesn't perform tasks as they expected it to.

Decreased satisfaction: Lack of consideration for user behavior can end up taking the form of a product that feels clunky and unsatisfactory.

Negative reviews: Users may leave negative feedback on various platforms, which can damage the reputation of the product and the brand.

Loss of trust: A product that fails to meet user needs can erode trust in the brand—and it’s something that can make it far harder to retain customers or even acquire them in the first place.

Wasted resources: Large amounts of time and money end up vanishing into the design and development of features that really don’t resonate with users.

Reduced revenue: Poor user experience can bring on lower sales and a drop in potential revenue, too.

Lack of innovation: When a brand fails to understand user behavior, it’s a mistake that can cost in the form of missed chances for innovation, too. Designers won’t be able to leverage insights that could lead to product improvements or service enhancements.

Inability to scale: If a design solution doesn’t account for user behavior, it may face big challenges when the brand tries to scale it—or evolve it—with market demands.

Exclusion of users: If designers don’t consider the diverse behaviors and needs of all potential users, the product may end up not being accessible to everyone—particularly to users with disabilities. Legal problems could arise as a result.

See why accessibility is such a fundamental issue in UX design in this video:

Accessibility ensures that digital products, websites, applications, services and other interactive interfaces are designed and developed to be easy to use and understand by people with disabilities. 1.85 billion folks around the world who live with a disability or might live with more than one and are navigating the world through assistive technology or other augmentations to kind of assist with that with your interactions with the world around you. Meaning folks who live with disability, but also their caretakers,

their loved ones, their friends. All of this relates to the purchasing power of this community. Disability isn't a stagnant thing. We all have our life cycle. As you age, things change, your eyesight adjusts. All of these relate to disability. Designing accessibility is also designing for your future self. People with disabilities want beautiful designs as well. They want a slick interface. They want it to be smooth and an enjoyable experience. And so if you feel like

your design has gotten worse after you've included accessibility, it's time to start actually iterating and think, How do I actually make this an enjoyable interface to interact with while also making sure it's sets expectations and it actually gives people the amount of information they need. And in a way that they can digest it just as everyone else wants to digest that information for screen reader users a lot of it boils down to making sure you're always labeling

your interactive elements, whether it be buttons, links, slider components. Just making sure that you're giving enough information that people know how to interact with your website, with your design, with whatever that interaction looks like. Also, dark mode is something that came out of this community. So if you're someone who leverages that quite frequently. Font is a huge kind of aspect to think about in your design. A thin font that meets color contrast

can still be a really poor readability experience because of that pixelation aspect or because of how your eye actually perceives the text. What are some tangible things you can start doing to help this user group? Create inclusive and user-friendly experiences for all individuals.

Privacy concerns: If designers ignore user behavior around privacy, it’s a potentially hazardous thing—and it can lead to design decisions that compromise user data. That could potentially violate privacy laws and regulations.

Non-compliance penalties: Products that fail to consider user behavior in compliance-related scenarios may face legal penalties—again, a hazard.

Losing to competitors: If competitors better understand—and cater to—user behaviors, they can easily outperform products that don’t prioritize UX in their design.

Remember, user behavior is a complex consideration and a multidimensional one, too. It’s a multifaceted concept that goes far beyond mere clicks and scrolls—and it delves into the realms of cognitive psychology and human perception. A myriad of factors have a big bearing on user behavior. What’s more, it’s not static—and it’s something that can change over time as a user learns, adapts or develops new habits. Designers have got to understand their users’ behaviors—and at the deepest level possible. That’s key to how they can create the best information architecture in user interface (UI) designs, well-considered product designs, and much more.

To design for users’ and customers’ behavior takes much research and data-driven decisions about products experience, expectations, contexts and far more.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Take our User Research – Methods and Best Practices course.

Consult our 5 Ways to Use Behavioral Science to Create Better Products piece for helpful tips.

Read our Emotional Drivers for User and Consumer Behavior piece for additional insights.

Refer to 15 Steps to Understand & Influence User Behavior: A Deep Dive by Adam Fard for many in-depth points and helpful tips.

Read Navigating the Psychology of UX: Understanding User Behavior by MVP Catalyst for more information.

To start—identify key performance indicators (KPIs) that are in line with your business goals. These are things that could include metrics like page views, bounce rates, conversion rates and user engagement levels.

Once you’ve set these objectives, use analytics tools to collect data on user interactions with your product or website. Tools such as Google Analytics or Mixpanel let you track how users navigate through your site, what actions they take—and where they drop off. This data provides insights into user preferences and pain points.

Analyze this data to find patterns and trends in user behavior. For example, if you notice a high bounce rate on a particular page, it’s a possible indicator that users find the content irrelevant—or difficult to understand. And when you make informed adjustments based on these insights, you can improve the user experience.

What’s more, think about conducting A/B testing—to validate your findings and hypotheses. To A/B test, create two versions of a webpage or product feature to see which is the one that performs better with your audience.

Take our Master Class Design with Data: A Guide to A/B Testing with Zoltan Kollin, Design Principal at IBM.

Yes—interviews, focus groups and observations stand out as powerful techniques to collect valuable qualitative data.

When you hold interviews, you engage directly with users to ask about their experiences, preferences and challenges—and it's something that offers rich, nuanced data that quantitative methods might miss. Similarly, focus groups bring together a small group of users to discuss a product, service or concept. And in this setting, participants feel encouraged to express their thoughts and feelings openly. That’s a great way that offers diverse perspectives on user behavior.

To make observations, designers watch users as they interact with a product or service—and, importantly, it’s best that it happens in their natural environment. This method helps weed out usability issues, plus understand how users navigate and experience a product—something that provides real-world context to your findings.

Design Psychologist Ditte Hvas Mortensen explains methods and best practices of qualitative research in this video:

In this presentation, we look at how user research fits into your design process and when to do different types of user studies. If you decide to invest time in doing user research, it's important that you time it so that you get as much out of your efforts as possible. Here, we look at when you should do different types of user research and how research fits into the different work processes.

Before you can decide when to do user research, you have to clarify *why* you're doing user research. You need different kinds of insights at different times in your design process. Let's have a look at the overall reasons for doing user research. You can do user research to ensure that you have a good understanding of your users; what their everyday life looks like; what motivates them, and so on. If you understand the people who use your product, you can make designs that are relevant for them. This type of research is typically *qualitative interviews and observations*.

You can also do tests of the user experience to ensure that your design has a high level of usability. Finally, you can evaluate on the impact of your design – for instance, on the number of customers or efficiency of work processes. As you can probably see, the different types of research fit into the design process in different ways. Let's start by looking at how each type of research fits into a simplified timeline for product development. Afterwards, we'll look into how user research fits into different types of development processes.

Research to ensure that your design is relevant to your users will typically be interviews and observations at the user's home or another relevant context. Since research to ensure that you create relevant products is meant to influence what type of product you will develop, most of this research takes place at the *start* of the development process, either *concurrently* with ideation work or *before* any concept work is done. You can also do research to validate your design direction, once you've developed some concept ideas

that you can show prospective users or during early product development. After release, you can do the same type of research to understand how customers are using your product, to explore if they need other features or offer opportunity scoping for your next project. And that, of course, leads you back to the beginning of your next product development process. Research to ensure that your designs are easy to use is mostly done as usability tests. It's important to start usability testing as early in the design or development process as possible

so that you have time to make changes to your design if the tests show that changing the design will benefit the product. If you use paper prototypes or similar materials, you can do early user testing before you have an interactive interface. User testing works well in an iterative process where you continually do user tests to ensure that your design is easy and pleasurable to use. Finally, research to measure the impact of your design mostly takes place *after* your product is released. The studies can then lead to new development and design changes.

If you're working on web-based products such as apps and web pages, it makes sense to keep evaluating on the user experience after your first release. One thing is a simplified timeline, but when you can do user research and how much research you can do really depends on what type of development process you work in. You can fit user research into most work processes depending on how ambitious you are. But it's easier in some work processes than in others. Let's take a look at what a work process that's optimized for user research looks like.

*User-centered design* is an overall term for work processes that place the needs and abilities of the user at the center of the development process. It's been described in different terms, but overall it's an iterative process where the first step is *user research* to ensure the relevance of the product. The second step is to *define* concepts based on user insights. The third step is *design and development*. And the fourth step is *user-testing the solution*. Ideally, this iterative process continues until evaluations show that the product is ready to be released.

After release, evaluations of the customer experience might lead to further development. By the way, design thinking is one of the most well-known user-centered work processes. As you can see, the steps involved in design thinking are almost identical to the overall steps of the user-centered design process. When you work in a user-centered process, user research is an integrated part of that process. But, in reality, many work processes are either not like that or deviate from the basic process in different ways.

So, how do you approach user research if you don't work in a clear-cut user-centered process? If research is not an integrated part of your work process and it's not up to you to change the way of working, you can still do user research, but it's up to you to decide when and how. So, let's look at some rules of thumb for deciding if, when and how to do user research. The sooner in your process you can do research, the bigger the impact of your research will be.

If you can do research before development starts, you can help ensure that you work on products that are relevant to your users. If you can do research early in development, you have more time to make changes to ensure great user experience before your product is released, and so on. Sometimes, you work in projects where you're not involved in all phases of the development. But you can still do smaller research projects that influence the part of the project you *are* working on. If you're a UX designer who's not involved in early concept development, it still makes a lot of sense to do *iterative user testing* of your designs.

If you don't have a process for how to handle research results, you should stick to research where you also have influence on any design changes that your research brings about. If you *are* involved in planning your development process, make sure that you schedule in some time to do user research. That way, you can be *proactive* with your research rather than reactive, so you don't have to scramble for resources when you suddenly need research to support your design decisions.

Sometimes, you don't have the resources to do all the user research you'd like to do. In that case, think about which type of research will have the *biggest impact* on your particular project and prioritize doing those studies. If you have influence over how you plan your development, iterative processes are almost always preferable when it comes to getting the most out of your user research. Iterative processes make you open to changing the end goal of your design based on the results of your user research.

In many projects, your time and resources to do user research are scarce. Luckily, you can do a lot with a little. You can, for instance, do user tests with paper prototypes rather than with fully interactive prototypes that require software programming. Just remember that the *validity* of your research is always the most important thing. So, if your time and resources for doing research are so limited that your results won't be sensible, it's better *not* to do any research. Best case = you'll waste your time and nothing comes from it.

Worst case = insights that don't really represent the user will impact important design decisions. Similarly, if you're working on a project that could benefit from user insights but you don't have the time or resources to make any design changes based on your research, you should save your research efforts for another time when they make more sense. So, what's the take-away? User research fits into the development process on all stages, depending on why you want to do user research. When you should do research, and what type of research you can do, depends on what your work process looks like.

If you work in a user-centered design process, user research is an integrated part of the process. If you *don't* work in a user-centered design process, it's up to you to make smart decisions about when and how to do research.

In web design, users often follow specific behavior patterns—and they’re patterns such as scanning content, preferring simplicity and demanding quick results. Firstly, most users scan web pages in a specific pattern—one that often resembles the shape of the letter F. They focus on headlines and the beginnings of paragraphs—which makes it crucial to put important information at these points.

Simplicity is another key factor in user behavior—and a big one. Users do tend to favor websites that offer a clean design and intuitive navigation. Overly complicated layouts or too many choices are things that can overwhelm users. This can lead to frustration and—ultimately—cause them to leave the site.

What’s more, users typically seek immediate satisfaction from their web interactions. They expect web pages to load quickly—and they want to find the information they need without excessive scrolling or clicking. Delays or hard-to-find information can deter users.

Design Psychologist Ditte Hvas Mortensen explains essential principles that ensure how a design can be engaging, simple to navigate and quick to satisfy user needs, and so enhance the overall user experience.

Cultural differences have a massive impact on user behavior—in diverse ways. These differences influence preferences, decision-making processes and interaction styles with websites and digital products. For example, color perceptions vary widely across cultures—and, for instance, what signifies joy and prosperity in one culture might well represent mourning in another. Designers have got to really consider these variations if they’re to ensure their creations resonate positively with target audiences globally.

What’s more, the structure and content layout preferences can differ based on cultural backgrounds. Users from Western cultures might prefer a much more linear, individual-focused navigation—meanwhile, those from Eastern cultures may appreciate a more holistic approach, one that emphasizes community and harmony. When designers understand these preferences, it lets them tailor user experiences that feel more intuitive and engaging to different cultural groups.

Language and communication styles are things that also play a critical role in shaping user behavior. High-context cultures rely on implicit communication and context clues—so calling for designs that are rich in visual symbolism and nuance. By contrast, low-context cultures tend to favor explicit, direct communication—something that demands clear and straightforward text.

Professor Alan Dix explains why it’s important to design with the users’ culture in mind:

As you're designing, it's so easy just to design for the people that you know and for the culture that you know. However, cultures differ. Now, that's true of many aspects of the interface; no[t] least, though, the visual layout of an interface and the the visual elements. Some aspects are quite easy just to realize like language, others much, much more subtle.

You might have come across, there's two... well, actually there's three terms because some of these are almost the same thing, but two terms are particularly distinguished. One is localization and globalization. And you hear them used almost interchangeably and probably also with slight differences because different authors and people will use them slightly differently. So one thing is localization or internationalization. Although the latter probably only used in that sense. So localization is about taking an interface and making it appropriate

for a particular place. So you might change the interface style slightly. You certainly might change the language for it; whereas global – being globalized – is about saying, "Can I make something that works for everybody everywhere?" The latter sounds almost bound to fail and often does. But obviously, if you're trying to create something that's used across the whole global market, you have to try and do that. And typically you're doing a bit of each in each space.

You're both trying to design as many elements as possible so that they are globally relevant. They mean the same everywhere, or at least are understood everywhere. And some elements where you do localization, you will try and change them to make them more specific for the place. There's usually elements of both. But remembering that distinction, you need to think about both of those. The most obvious thing to think about here is just changing language. I mean, that's a fairly obvious thing and there's lots of tools to make that easy.

So if you have... whether it's menu names or labels, you might find this at the design stage or in the implementation technique, there's ways of creating effectively look-up tables that says this menu item instead of being just a name in the implementation, effectively has an idea or a way of representing it. And that can be looked up so that your menus change, your text changes and everything. Now that sounds like, "Yay, that's it!"

So what it is, is that it's not the end of the story, even for text. That's not the end of the story. Visit Finland sometime. If you've never visited Finland, it's a wonderful place to go. The signs are typically in Finnish and in Swedish. Both languages are used. I think almost equal amounts of people using both languages, their first language, and most will know both. But because of this, if you look at those lines, they're in two languages.

The Finnish line is usually about twice as large as the Swedish piece of text. Because Finnish uses a lot of double letters to represent quite subtle differences in sound. Vowels get lengthened by doubling them. Consonants get separated. So I'll probably pronounce this wrong. But R-I-T-T-A, is not "Rita" which would be R-I-T-A . But "Reet-ta". Actually, I overemphasized that, but "Reetta". There's a bit of a stop.

And I said I won't be doing it right. Talk to a Finnish person, they will help put you right on this. But because of this, the text is twice as long. But of course, suddenly the text isn't going to fit in. So it's going to overlap with icons. It's going to scroll when it shouldn't scroll. So even something like the size of the field becomes something that can change. And then, of course, there's things like left-to-right order. Finnish and Swedish both are left-to-right languages. But if you were going to have, switch something say to an Arabic script from a European script,

then you would end up with things going the other way round. So it's more than just changing the names. You have to think much more deeply than that. But again, it's more than the language. There are all sorts of cultural assumptions that we build into things. The majority of interfaces are built... actually the majority are built not even in just one part of the world, but in one country, you know the dominance... I'm not sure what percentage,

but a vast proportion will be built, not just in the USA, but in the West Coast of the USA. Certainly there is a European/US/American centeredness to the way in which things are designed. It's so easy to design things caught in those cultures without realizing that there are other ways of seeing the world. That changes the assumptions, the sort of values that are built into an interaction.

The meanings of symbols, so ticks and crosses, mostly will get understood and I do continue to use them. However, certainly in the UK, but even not universally across Europe. But in the UK, a tick is a positive symbol, means "this is good". A cross is a "blah, that's bad". However, there are lots of parts of the world where both mean the same. They're both a check. And in fact, weirdly, if I vote in the UK,

I put a cross, not against the candidate I don't want but against the candidate I do want. So even in the UK a cross can mean the same as a tick. You know – and colors, I said I do redundantly code often my crosses with red and my ticks with green because red in my culture is negative; I mean, it's not negative; I like red (inaudible) – but it has that sense of being a red mark is a bad mark.

There are many cultures where red is the positive color. And actually it is a positive color in other ways in Western culture. But particularly that idea of the red cross that you get on your schoolwork; this is not the same everywhere. So, you really have to have quite a subtle understanding of these things. Now, the thing is, you probably won't. And so, this is where if you are taking something into a different culture, you almost certainly will need somebody who quite richly understands that culture.

So you design things so that they are possible for somebody to come in and do those adjustments because you probably may well not be in the position to be able to do that yourself.

Copyright holder: Tommi Vainikainen _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Copyright holder: Maik Meid _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons _ Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Norge_93.jpg

Copyright holder: Paju _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons _ Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kaivokselan_kaivokset_kyltti.jpg

Copyright holder: Tiia Monto _ Appearance time: 2:56 - 3:03 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons _ Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Turku_-_harbour_sign.jpg

User behavior varies significantly between different devices—such as mobile and desktop—a variation that primarily stems from the context in which users access these devices and the inherent capabilities or limitations of each device.

On mobile devices, users typically are after quick information—or they’re performing specific tasks like checking email or social media. The smaller screen size of mobile devices calls for really concise content—as well as simplified navigation—to enhance usability. Touchscreen functionality dictates the shape the design takes, too. It’s something that requires larger buttons and touch-friendly interfaces to accommodate finger tapping instead of mouse clicks.

On the other end of the scale, desktop users often involve themselves in more complex tasks—or they have longer content consumption sessions, such as doing detailed research or watching videos. The larger screen size supports more extensive content display and complex interactions—and these include multi-window browsing and extensive use of keyboard shortcuts. So, desktop environments call for more intricate designs—ones that include detailed visuals and complex navigational structures.

Dive into the nuances of designing for mobile interactions with this video.

In this five-step process to designing for mobile, I want to point out some of the aspects or steps that are so critical and tell you why they're so critical and explain a little bit about how they work. The first step, *assess*, is requirements, your internal priorities,

your business objectives. And so – that's for step one – the last step, step five, should be familiar as well, it's *sketch*. So, we'll also add sketch, review, refine and have that sort of iteration. But it's what happens in steps two, three and four that are really, really critical and make the difference in a mobile UX design that outperforms and differentiates and creates a very, very deep bond with users and in a way that what we call *user adoption*.

So, step two, *understand* user needs, and that means understand their context of use, problems they're trying to solve, their tasks, their goals, all the things that make up personas, and then make up journey maps. Once you do that very crucial user research step, it's step three where you *define* your value proposition and your emotional value. So, emotional value is what users get from the app so that you essentially support their tasks,

you support their goals, you support a social aspect of their experience. You help them by giving them features and functionality that they find useful. Maybe you surprise them pleasantly, delight them. Understand their cultural needs. Understand their safety needs. Whatever it might be, you define that value proposition,

but also emotional value, that chance to connect with a user in such a way that they feel at home with your app or mobile content. So, that's step three. Step four is where you take what you've learned from user needs and from defining your value proposition and your emotional value, and you then *create a UX strategy* that's like a blueprint for when you get to sketching in the next step.

So, a differentiated UX strategy is something that makes your app special and connects with your users in a special way. You can't just generate this internally. A lot of product folks have pressure in their jobs, product managers, to differentiate, and they typically rely on market research, focus groups, surveys, that kind of thing. That's market research. And so, what we're talking about is if you get into the behavior of your users,

if you really dig into their contextual experience and what surrounds it and what they do as they go through their day and their lives and how they live it – if you get into that, then you can understand their needs, define their value proposition and their emotional value in a way that helps you differentiate. So, it might be how you approach the design, what features you drop

or that you add. In other words, the priorities and the good decision-making is what all of UX is about. It's about good design decision-making, And this five-step process is based on a very powerful and proven approach that I've taken in my work over the years, and this is basically the way to do it.

Common patterns of user behavior in web design include scanning content, preferring simplicity and seeking quick satisfaction. Users typically scan web pages in an F-shaped pattern—paying more attention to headlines, bullet points and the beginnings of paragraphs—and so calling for designers to place key information at the top and make it easily skimmable.

Simplicity plays a massive role in user behavior, too. That’s because users favor websites with a clean, uncluttered design and intuitive navigation. Overly complicated designs or navigation can overwhelm users and put them off a website or app. So, it’s best to focus on core content and functionality, avoiding unnecessary elements that do not add value.

What’s more, users seek immediate gratification when they’re interacting with websites. They expect fast-loading pages and want to find the information they need quickly—and without excessive scrolling or clicking. Slow-loading pages or hard-to-navigate websites are things that frustrate users—and can drive them away, fast.

Take our UI Design Patterns for Successful Software course to help meet users’ expectations in design.

Designers can stay informed about technological advancements, societal shifts and emerging design trends—great ways to stay a step or two ahead of things. One effective approach is to do ongoing user research—including surveys and interviews—to understand evolving needs and preferences. This continuous engagement really helps them spot emerging patterns—and adapt their designs proactively.

Analyzing data from website analytics tools offers insights into user behavior changes, too. Metrics such as page views, bounce rates and conversion rates can indicate shifting interests or usability issues—and so guide designers to make informed adjustments.

What’s more, to keep an eye on industry trends and competitor activities can reveal broader shifts in user expectations. Designers can attend conferences, participate in forums and follow thought leaders in the field—great ways to stay updated.

Another strategy is to adopt a flexible design philosophy—and to design systems that permit easy updates and iterations enable designers to respond quickly to user behavior changes—without them having to overhaul entire projects.

Last—but not least—to involve users in the design process through beta testing and feedback loops makes sure that products evolve in line with what the user needs are.