The 'Rules of Play': Directing Gamer and User Behaviour

- 604 shares

- 9 years ago

Games User Research focuses on understanding players' behavior, interactions, and experiences in video games. Researchers use methodologies like observations, interviews, and surveys to gather valuable data. This data helps improve games, remove bugs, and increase player experience.

Steve Bromley, a games user research expert who has worked with companies such as Sony Interactive Entertainment and EA, gives an overview of Games User Research:

Games user researchers combine principles of psychology, human-computer interaction, and UX design to study how players interact with video games. Their studies uncover potential issues in the game mechanics, user interface, or any other aspect that could negatively affect the player's experience.

Games user researchers work closely with game designers, producers, and the UX team to ensure the game aligns with the designer’s vision and meets the player's expectations.

Researchers analyze the collected data to identify patterns, trends, and potential usability issues. Then, they communicate these findings to the design team in a way that is easy to understand. Their conclusions create empathy between the design team and the players. Researchers also provide actionable recommendations to improve the game's design and enhance the player experience.

While games user research and user research are similar, there are a few key differences.

User researchers focus on user needs—what users want to achieve, their challenges, etc.

For example, the design team for an e-commerce website creates a mega menu to help users see all product categories at once. However, the research team finds that their users find it challenging to find the products because of the way they are ordered on the menu. The design team incorporates this insight to restructure the navigation. The navigation is a functional element to help users complete a goal, in this case, to find products quickly.

On the other hand, games are a form of entertainment, an art form, like movies. Scriptwriters write movies with the intention of creating an emotional response in the viewer. Game designers do the same but for games. Therefore, in games, user researchers approach their work from the designer’s point of view. Unlike other products where designers rely on user research to decide what to create, game designers begin with a vision, and researchers evaluate if users' experience matches the designers’ vision.

For example, if the purpose of a horror game is to make players feel scared and nervous, the research team’s goal is to find out how the players are feeling. If the players are not “scared enough,” the designer can use research insights to reach their vision.

User researchers ask users, “What difficulties do you encounter while using our platform/product/service?” Designers use this research to remove these difficulties.

However, in games, difficulty improves the experience. It's essential as it keeps players interested while enhancing their skills. As players overcome challenges, they have more fun.

An excellent example of difficulty in games is the popular game series Dark Souls. The Dark Souls games are famous for being incredibly difficult to complete. However, this is what has made them popular. Players enjoy the satisfaction of overcoming the challenges of the game.

© Bandai Namco, Fair Use

Researchers need to identify when difficulty is intentional or accidental:

When difficulty is intentional, it elevates the gaming experience. As players move through the game, they will become bored if it does not get progressively more difficult. As intentional difficulty increases, so does the skill of the player. Equally, If level 5 is easy compared to level 3, this will not meet the players’ expectation of increasing difficulty through the game.

When difficulty is accidental, it reduces the player's enjoyment level. The game does not immerse the player, who may eventually give up. Examples of unintentional difficulty include glitches and bugs, poor balancing, or illogical changes in gameplay.

In the massively multiplayer online game World of Warcraft, there was an incident known as the “Corrupted Blood Incident.” The game's developers introduced a new enemy who cast a spell on players, giving them a contagious disease. Only when a player defeated the enemy was the disease healed. Many players left the area where the enemy existed without beating it and spread the disease throughout the game. This unintended consequence resulted in many players having difficulty playing the game. Their characters would get infected, die, respawn, and then catch the disease again, repeating the cycle—an example of accidental difficulty.

© Blizzard Entertainment, Fair Use

Game researchers need to understand secrecy's crucial role in game development. Marketing and advertising are critical to a game’s commercial success. Game studios usually protect their games to prevent leaks that could disrupt marketing strategies.

Secrecy directly impacts research methods, especially those involving the public. Some research methods, like public surveys, are not usable when you must preserve secrecy. Therefore, the research methods in games user research can differ from those used in other industries.

“Games user researchers bring structure to the playtesting process so that game developers are confident that the game they’re making is experienced by players in the way they want them to be experiencing it.”

– Steve Bromley, Games user research expert

The video game industry is highly competitive. Studios aim to create games that captivate players and keep them engaged so they don’t switch to a competitor’s game. Games user researchers help achieve this by identifying issues to fix throughout development.

Steve Bromley explains the concept of playtesting and why applying user research practices to the process is important:

Let’s look at a simple scenario: a game studio is building a game. They know what type of game they want to make and begin developing it.

Only the game studio employees play the game throughout the development process. Since they’ve built it, they are biased and only identify and fix issues they find themselves. This approach saves them time and money and means they can launch the game sooner.

When the game launches, they look at the user feedback and discover their game is filled with bugs. Players also find the game too complicated and don’t understand how to play. Ultimately, the game doesn't sell many copies, and the industry considers it a failure.

Throughout the development process, the game studio employs user research. Since the users testing the game are new to it, they highlight and identify many issues the studio hadn’t noticed.

Using these findings, they fix the issues and continue to employ user research to identify and fix further issues. This approach adds extra time to the development process and costs money, but the studio feels more confident their game will succeed.

When the game launches, the feedback is positive, and the players enjoy the game. Ultimately, the game sells many copies, and the industry considers it successful.

The process of game design is, of course, much more complex than this. However, these scenarios show how vital games user research is to game development.

Researchers can provide important information to guide the design team when they understand the players' preferences and behaviors. This results in better game experiences, higher player retention rates, and commercially successful games.

Games user researchers use many of the same user research methods employed in other industries, such as observation, interviews, surveys and analytics.

Once the development team has a working version or demo of the game, researchers will do most of their user research through playtesting. Playtesting is where users play the game, and researchers collect data using qualitative and quantitative approaches.

Researchers conduct playtesting with one-to-one or small groups and large groups of 20+ players (also known as mass playtesting or multi-seat testing).

Typically, researchers employ qualitative methods for small groups and quantitative methods for mass playtesting.

Researchers use qualitative research to observe and talk with players in smaller groups to understand them better. Qualitative research helps us discover how players feel, act, and think, leading to better designs.

Qualitative research methods include:

User interviews – It's helpful to talk to players throughout game development. In the ideation phase, you can understand their behaviors and preferences. Later on, through playtesting, you can ask about their experience with the game and how it makes them feel.

Observation – Watch your players as they play. Record their choices, successes, and struggles.

Diary Studies – Participants record their thoughts, feelings, and experiences. This approach allows you to gain insights into users' experiences over a period of time.

Researchers use quantitative research to study people's attitudes and behaviors based on statistical data. Due to the importance of secrecy in games, quantitative research methods like public surveys may not be available during game development. This research method is more likely to result in someone leaking the game than if you work directly with a smaller group of users.

However, games have many variables and require many users to test them. For this reason, game studios employ mass playtesting, where dozens of players test the game simultaneously. Given these large user groups, researchers can use quantitative methods to collect data.

Quantitative research methods include:

Analytics – Monitor players' actions while they play. Examples of analytics include:

Time spent playing.

How many times players had to restart a level.

How many items players have collected.

Surveys and Questionnaires – Gather information from players after they have played the game. Use carefully crafted questions to understand how players felt and what they experienced when they played the game.

Researchers conduct research throughout the whole game development process. It is essential to keep the bridge between designers and players strong. This empathy avoids scenarios where designers build features and find out too late that players don’t like them.

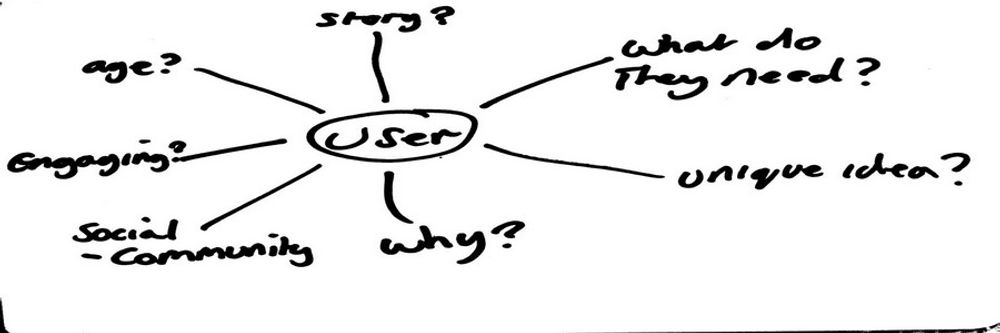

In the ideation phase, game designers want to understand:

Do users find this idea fun?

Is it worth building a game from this idea?

Does this idea give users the emotional response and reaction we want?

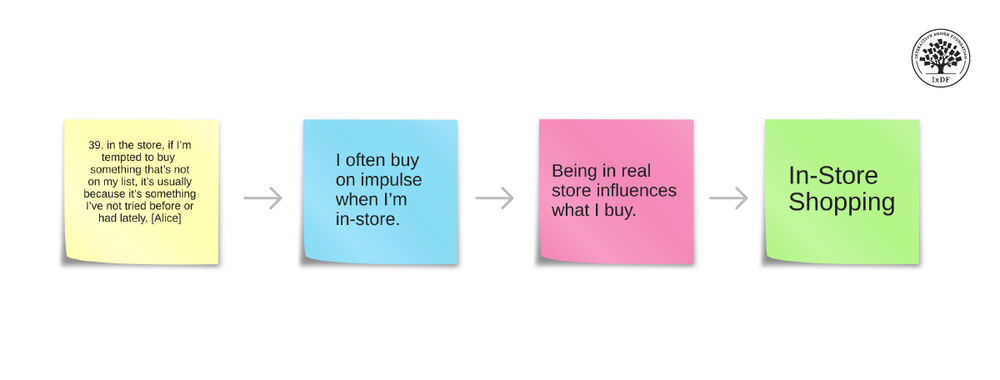

To answer these questions, researchers speak to target users of the game. Since secrecy is crucial in game design, researchers typically use qualitative methods such as interviews and diary studies. This research helps design teams create mental models of their target users to understand their expectations and how they think.

For example, a design team plans to build a platform game like Super Mario. Before they begin development, they interview users who love platform games. Through this research, they discover players prefer platform games with strong narratives. When the character grows, learns, and changes over the story's progression, it makes it worth investing their time in the game.

As soon as designers have a playable demo, they playtest it. The players will reveal if the basics of the game are fun.

At this stage, researchers can begin using the observation method. By watching how users play and approach the game, they can understand essential information to inform game development.

For example, in the platform game, researchers might discover that players try to explore areas of the level that don’t exist. This discovery can translate into a design element where the team includes secret and hidden areas to add further engagement and player retention to the game.

The production phase is where studios build the whole game. Game studios conduct playtesting regularly to ensure that the game meets the designers' vision and that players enjoy it.

Since mass testing is now possible, researchers can employ quantitative methods like analytics to understand where designers can improve the game.

For example, players may spend more time on a particular level than others. These findings show that the level's objectives need to be clearer and that it should be easier for players to achieve them.

During post-production, studios balance and tune the game. Researchers gather much information from playtests at this stage to inform final design decisions.

For example, a game studio builds a game where you can play multiple characters. The majority of players are choosing one character in particular. Researchers discover that this is because, compared to the other characters, this specific character is much stronger. These findings inform the design team that they must refine this character to make them equally powerful as the other characters.

Before the widespread use of the internet, video game developers could not update games after releasing them. Occasionally, developers released updated versions of popular games with improvements, but this was rare.

Most game developers now have the option to update their games after launch. Since secrecy is no longer a concern, researchers can use quantitative methods such as public surveys and questionnaires to gather vast amounts of player feedback and data. With this new data, studios can fix previously undiscovered issues and improve the player experience.

Some game developers also employ early access. Early access is when developers release a game unfinished before they complete development. Indie developers and crowdfunded games often use this tactic to fund the game's completion. Early access contradicts the need for secrecy in game development but ultimately can be more beneficial to some game studios.

Early access is a particularly effective way to gather study participants. Since players are usually fans of the game genre or developer, they will happily play an unfinished game.

An example of a successful early access release is the role-playing game Baldur’s Gate 3. Developer Larian Studios released the early access version of the game in October 2020. Baldur’s Gate 3 is a sprawling, incredibly complex game with many paths players can take. The early access period lasted almost three years until Larian Studios released the game in September 2023. Early access allowed Larian Studios to collect vast user feedback to improve the game. Baldur’s Gate 3 became one of the best-selling, top-rated games of 2023.

© Larian Studios, Fair Use

Researchers use a 4-step process to carry out their study.

The first step in the research process is to define the objectives—what is the purpose of the research? What do you want to find out? Talk to the game designers, producers, and UX designers to understand what they want to discover.

Researchers may also read through previous research and analysis to understand what others have uncovered. It is also essential they play the current version of the game, as well as similar games from competitors.

Armed with this knowledge, researchers can answer the following questions:

What goals do we want to reach with our research, and what do we want to learn from it?

What plan do we have to carry out the study?

When are we scheduling the study, and who are our targeted participants?

Which stakeholders will benefit from the study results?

Those working individually or on a small design team may already know the purpose of their research. However, anyone conducting research must ask themselves these questions to ensure they get the data they need.

Depending on the research objectives and the game development stage, researchers choose the appropriate research method(s).

If the research aims to understand how a game level makes your players feel, they may use a qualitative method like user interviews. On the other hand, they might use a quantitative method like analytics to learn how long players spend on a certain level.

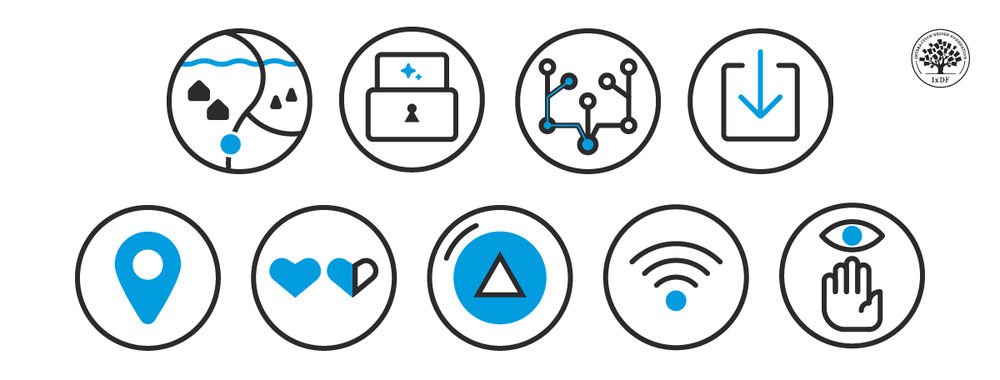

Researchers also need to gather research participants. Design consultancy IDEO's uses a method to recruit “Extremes” and “Mainstreams.” This method enables researchers to cover the entire spectrum of the target group.

Extremes are users who, for example:

Have minimal gaming experience.

Prefer other genres.

If these participants enjoy the game, most other players will, too.

If you use the extremes and mainstreams methods, remember to include the mainstream users as well. Mainstream users are the ones who represent the majority of your target group.

Always include a small number of extreme users in your study. They are more likely to highlight issues only newcomers will encounter with your game.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Many researchers also act as moderators when using qualitative research methods like interviews or observations. Moderators help their research participants feel comfortable. A solid ability to empathize and be inquisitive is beneficial to being a moderator.

Once researchers have gathered their data, they analyze it and present their findings. How researchers present their data will depend on the research purpose and methods. However, it is essential to present data in a way the design and development teams can easily understand.

Take our course User Research – Methods and Best Practices to build your foundational knowledge of user research.

Watch Steve Bromley’s Master Class, How to Become a Games User Researcher, for insights from a GUR expert.

You can also read Steve’s blog to learn about GUR in more detail.

Learn about the differences and similarities between game and mainstream user research.

Access a library of presentations from the Games User Research Summit, presented by industry experts.

Some highly cited research on games user research and related topics include:

Desurvire, H., & El-Nasr, M. S. (2013). Methods for Game User Research: Studying Player Behavior to Enhance Game Design. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 33(4), 82-87.

Mirza-Babaei, P., Nacke, L., & Drachen, A. (2018). Games User Research Methods. In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play Companion Extended Abstracts (CHI PLAY '18 Extended Abstracts) (pp. 1-4). Association for Computing Machinery.

Nacke, L. E. (2017). Games user research and gamification in human-computer interaction. XRDS, 24(1), 48–51.

Smeddinck, J., Krause, M., & Lubitz, K. (2020). Mobile Game User Research: The World as Your Lab? [Epub ahead of print]. arXiv. 2012.00378

Shin, Y., Kim, J., Jin, K., & Kim, Y. B. (2020). Playtesting in Match 3 Game Using Strategic Plays via Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access, 8, 51593-51600.

Lee, I., Kim, H., & Lee, B. (2021). Automated Playtesting with a Cognitive Model of Sensorimotor Coordination. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM '21) (pp. 4920–4929). Association for Computing Machinery.

Mirza-Babaei, P., Stahlke, S., Wallner, G., & Nova, A. (2020). A Postmortem on Playtesting: Exploring the Impact of Playtesting on the Critical Reception of Video Games. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '20) (pp. 1-12). Association for Computing Machinery.

Ariyurek, S., Surer, E., & Betin-Can, A. (2022). Playtesting: What is Beyond Personas [Epub ahead of print]. arXiv. 2107.11965

Sevin, R., & DeCamp, W. (2020). Video Game Genres and Advancing Quantitative Video Game Research with the Genre Diversity Score. Computational and Game Journal, 9, 401–420.

Díaz, C., Ponti, M., Haikka, P., et al. (2020). More than data gatherers: Exploring player experience in a citizen science game. Qualitative User Experience, 5, 1.

If you’d like to cite content from the IxDF website, click the ‘cite this article’ button near the top of your screen.

Some recommended books on games user research and related topics include:

Bromley, S. (2021). How to be a games user researcher.

This book provides deep insights into contemporary topics important for games user researchers and UX designers. Steve Bromley covers a wide range of approaches and challenges in the industry. The book teaches how to develop essential skills like moderating, biometrics, and analytics.

Drachen, A., Mirza-Babaei, P., & Nacke, L. E. (2018). Games user research. Oxford University Press.

This book is essential for anyone working with players and games or other interactive entertainment products. Whether you are new to Games User Research or have plenty of experience, this book is suitable.

Hodent, C. (2018). The Gamer's Brain: How neuroscience and UX can impact video game design. CRC Press.

Celia Hodent provides an overview of cognitive psychology and neuroscience research and how to apply it to video game design. It covers attention, perception, memory, motivation, and emotion and provides practical advice on designing more engaging and enjoyable games for players.

Playtesting, a crucial practice in game design, offers researchers insights into real users' interactions in a game. You should follow these best practices when you conduct playtesting:

Define Objectives: Determine your playtest learning goals.

Choose Participants: Select a representative target audience.

Prepare Materials: Ensure a testable game/product state.

Create Environment: Set a conducive play/observation space.

Observe and Note: Watch and record participant interactions.

Ask Questions: Encourage open feedback from participants.

Analyze Feedback: Review and apply session insights.

Iterate, Repeat: Continue to improve via multiple tests.

Researchers will often use interviews to gain insights from users after playtesting. Ann Blandford, Professor of Human-Computer Interaction at University College London, explains the pros and cons of user interviews in this video:

Read our article How to Conduct User Interviews to learn more.

In games user research, researchers employ various tools to understand player behavior, preferences, and experiences. These tools include:

Analytics Software: Track in-game player behavior and metrics.

Survey Tools: Gather feedback on game design via surveys.

Game Testing Platforms: Collect player data using specialist software.

Eye Tracking Technology: Track player gaze for insight into attention focus.

Physiological Measurement Tools: Measure heart rate, brain activity, and signals for emotional and physical engagement insights.

Heat Maps: Discover a game's most interacted areas using user data.

Audio and Video Recording Tools: Capture player reactions during playtesting sessions.

William Hudson, User Experience Strategist, teaches you how to ensure you collect good quality data from your research:

Read our Ultimate Guide to learn how, when, and why to use surveys.

Researchers employ playtesting, surveys, and behavior observation in games user research to identify accessibility barriers, like issues faced by players with visual or hearing impairments.

They use these insights to develop game accessibility features that benefit all players. Features include settings that can be customized, such as text size and control schemes.

You should integrate accessibility early in game development, involve players with disabilities, and iterate based on their feedback.

Accessibility is a key consideration in inclusive design. Inclusive design is an approach to creating accessible products and experiences that are usable and understandable by as many people as possible. Katrin Suetterlin, UX Content Strategist, provides an overview of inclusive design:

Learn more in our course Accessibility: How to Design for All.

Recruitment for games user research studies is a crucial task. Researchers identify and engage with individuals who represent their target audience. To successfully recruit participants, you should follow these steps:

Define the Target Audience: Age, experience, preferences.

Recruitment Appropriate Users: Tap into social media, forums, and your existing user base.

Encourage Participation: Offer game credits, merchandise, and money.

Create a Concise Survey: Screen participants efficiently.

Ensure Ethical Practices: Transparency, data use, and confidentiality.

Plan for Dropouts: Over-recruit for reliability.

Maintain Communication: Inform participants about progress.

Seek Feedback: Improve future recruitment efforts.

William Hudson, User Experience Strategist, offers practical tips to ensure the effectiveness and efficiency of your recruitment process:

Learn more about qualitative user research in User Research – Methods and Best Practices.

Enroll in Data-Driven Design: Quantitative Research for UX for more on quantitative user research methods.

Games user researchers must prioritize ethical considerations to ensure respect for players. They must maintain integrity in research practices and responsibly use data. Key ethical considerations include:

Consent and Privacy: Obtain and respect player consent and privacy.

Transparency and Honesty: Ensure openness and honesty in research practices.

Data Security: Safeguard data confidentiality and security rigorously.

Avoid Bias: Strive to eliminate biases in research.

Minimize Harm: Design research to minimize participant harm.

Beneficence and Respect: Respect participant autonomy, dignity, and benefits.

Some games feature violence and other potentially distressing elements. Ann Blandford, Professor of Human-Computer Interaction at University College London, discusses how she asks research participants about emotionally charged and critical incidents:

To learn more, watch the Master Class Webinar Ethics In Design: A Practical Guide from Guthrie Weinschenk, COO of The Team W, Inc.

Games user research (GUR) uses crucial insights from psychology about player behaviors and motivations. Researchers use these insights to enhance gaming experiences.

Researchers focus on player psychology in GUR to improve game design and engagement. They understand player motivation through theories like flow theory, a state of mind where a person is completely absorbed and focused in an activity.

You can use psychology to create intuitive interfaces and positive game mechanisms. To do this, you must study players’ behavior and how they learn.

GUR includes usability testing, where researchers analyze player interactions to refine game mechanics and improve the player experience.

Psychology in GUR leads to more engaging, rewarding games, offering players more profound, meaningful experiences.

Alan Dix, Professor and Expert in Human-Computer Interaction, teaches you how psychological principles can enhance player engagement:

Celia Hodent, Ph.D., Game UX Strategist and author of The Gamer's Brain, teaches the cognitive science and psychology that support developing engaging video games in her Master Class, How to Design Engaging Products: Insights from Fortnite's UX.

A researcher must understand that game design user personas represent various player types. These personas focus design efforts on a relatable character set and avoid the complexity of endless player possibilities.

To develop user personas:

Gather user data through surveys for rich insights.

Analyze data to form main player archetypes.

Create detailed, engaging personas for each archetype.

Define goals and scenarios for each persona.

Reference personas in shaping game design elements.

Validate design choices and refine them based on feedback.

Frank Spillers, CEO of Experience Dynamics, teaches you how personas can guide design decisions:

Learn How To Create Actionable Personas in this Master Class from Daniel Rosenberg, UX Professor, Designer, Executive and Early Innovator in HCI.

Career paths in games user research (GUR) are diverse and dynamic. A career in GUR will offer you exciting opportunities if you are passionate about combining the science of user experience with the art of game design. Key career paths in GUR include:

User Research Analysts conduct user research and analyze player behavior and feedback. They provide insights to improve game design and player experience.

User Experience (UX) Designers for Games focus on designing user interfaces and creating seamless user experiences. They ensure the game is intuitive and enjoyable.

Game Data Analysts analyze in-game data to understand player behavior, preferences, and trends. This analysis informs game development and marketing strategies.

Playtest Coordinators organize playtesting sessions, gather feedback, and ensure the game meets user expectations.

Accessibility Specialists ensure that people with disabilities can play video games. They help to make game design more inclusive.

Elena Chapman, Accessibility Research Manager at Fable, explains what accessibility means and why it is crucial to create games that are inclusive for all players:

Learn more about accessibility in Elena’s Master Class Introduction to Digital Accessibility.

Developers employ games user research (GUR) to enhance gaming experiences when developing virtual reality (VR) games. Researchers use various methods like playtesting and biometric analysis to understand player interactions in VR.

Researchers observe player behavior and reactions in VR playtesting to identify usability issues and engagement levels. They use surveys, interviews, and biometric tools like eye tracking. These qualitative research methods help us understand player emotions.

Researchers apply GUR methods in VR to make informed decisions that improve user interfaces and game immersion. Insights from playtesting and biometric analysis help us to:

Refine game mechanics.

Enhance player emotional engagement.

In this video, researcher and professor Mel Slater explores design considerations for VR. He provides valuable context for applying games user research in VR game development:

Enroll in UX Design for Virtual Reality to develop your understanding of UX in VR.

You don't need a PhD to become a user researcher. Practical skills and experience are often more valued than a PhD.

User researchers use diverse methods to understand behaviors, needs, and motivations. Essential skills include empathy, observation, critical thinking, and communication.

Ann Blandford, Professor of Human-Computer Interaction at University College London, offers valuable insights into effective user research techniques:

To learn more about being a user researcher, read our 15 Guiding Principles.

To become a UX researcher with no experience, you should focus on UX research fundamentals. Learn UX design principles, user-centered processes, and research methodologies to understand user needs and behaviors.

Engage in self-learning with courses and materials on:

UX research methods.

Empathy skills.

Critical thinking skills.

Development in these areas is vital in UX research.

Volunteer, intern, or carry out research projects to gain practical experience. A portfolio displaying your projects and findings is vital if you aspire to be a UX researcher.

Networking is crucial for entering the UX field. Join communities, attend events, and seek mentorship from experienced UX researchers for industry insights and career advice.

A perfect place to start is the IxDF course, User Research – Methods and Best Practices.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Games User Research by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Games User Research with our course User Research – Methods and Best Practices .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your experts for this course:

Frank Spillers: Service Designer and Founder and CEO of Experience Dynamics.

Ann Blandford: Professor of Human-Computer Interaction at University College London.

Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!