How to Design Use Cases in UX

- 736 shares

- 2 mths ago

User stories are short statements about features, written from a user’s perspective. A well-defined user story does not spell out the exact feature, but rather what the user aims to achieve, to give teams the freedom to identify the best possible way to implement the feature.

Ideally, the team should draft the stories in collaboration with stakeholders and user researchers. While there is no standard format for creating user stories, teams commonly write them as single-line statements. Some teams may also include design deliverables such as personas, storyboards or short movies and include details about the users’ activities, thoughts and emotions.

User stories are commonly used in agile teams to facilitate planning. Each story should be small enough to fit into one sprint. The most common format for framing the story is:

As a

, I want , so that .

User stories were created as part of the move away from lengthy planning periods in software development in the 90s. Use cases, another type of story of use, were part of this longer process. While user stories effectively replaced use cases in many scenarios, they still draw inspiration from them, and in some cases, you may want to use use cases when more detailed stories are needed.

In this video, William Hudson, User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd, explains how use cases describe a system’s interactions with users and external events, helping you understand when they may be more suitable than user stories for detailed analysis.

While user stories are mostly written from the end users’ point of view, that’s not always true. Teams can write them from the perspective of business stakeholders, partners, and even employees and team members.

User stories are problem- or goal-oriented and do not include specific solutions or features. Instead, they aim to serve as a springboard for teams to ideate and arrive at the most optimal solution to solve the problem for the user. Here’s a hypothetical user story for a mobile application for diners:

“As a diner, I want to quickly locate good restaurants so that I can get good food fast.”

Notice that this user story doesn’t include specific features. These come later, when team members take the user story and work their way towards solutions or features, which, for this user story, could include:

Be able to save favorite restaurants.

Sort restaurants by location, reviews or delivery times.

View recommendations by friends.

While user stories may seem like simple statements, they can be tough to get right. This is where qualitative research techniques, including observations, contextual interviews, and other ethnographic methods, come into the picture. Designers and researchers can also use probe kits to ask users to document their days and capture their context, experiences and perspectives. The team can then collaboratively select the most relevant insights for the design problem and merge them into cohesive user stories.

The best stories are ones that lead to measurable outcomes. Examples of good outcomes are an X% increase in profile completion rates or an N% drop in payment flow errors. Outcomes that are tied to users or business goals free up the team to think about solutions to problems instead of churning out features for the sake of shipping something.

When the team begins work on a user story, they need not always understand the full scope of work since user stories are (intentionally) vague about what features the team should implement. To ensure that all team members are on the same page about what the user story should accomplish, product managers, designers and researchers often include acceptance criteria—what conditions the feature should fulfill to consider it done.

Because user stories focus on simple role labels, they rarely give you enough insight into the real people who will use your product. When a story begins with something like “As a user, I want…”, you learn nothing about who that person is, what they care about, or what might shape their behavior. This makes it harder for you to design with genuine user needs in mind or to understand how someone will actually experience your solution.

Persona stories give you a clearer path. Instead of referring to an anonymous role, you write from the perspective of a specific persona with real goals, motivations, and context. This helps you step into your user’s world and understand not only what they want to do but why. With that clarity, you can make better design decisions, anticipate challenges, and create solutions that feel natural and supportive to the people you are designing for.

In this video, William Hudson explains how persona stories, created collaboratively after user research and early design, help you base your decisions on genuine user needs and avoid the limitations of anonymous “As a user” stories.

For more practical insights on working on agile teams, take the course, Agile Methods in UX Design.

Want to know more about personas and how to use them effectively? Personas and User Research: Design Products and Services People Need and Want will show you how to gather meaningful user insights, avoid bias, and build research-backed personas that help you design intuitive, relevant products. You’ll walk away with practical skills and a certificate that demonstrates your expertise in user research and persona creation.

You can also discover how to put persona stories into action with an object-oriented approach to UI design, and design interfaces users love and developers love to build in our course Object-Oriented UI Design: Build Interfaces Users Love.

Agile is one of the most misunderstood methodologies in software development. Laura Klein breaks down common “anti-patterns” and how to avoid them, in this hour-long Master Class.

Find out more benefits of personas to your design process in our article, How Persona Stories Help You Design for Real People.

UX designers use user stories to keep the design process focused on real user needs. A user story is a short, simple statement that describes what a user wants to do and why. It helps teams build features that solve actual problems instead of just adding unnecessary functionality.

User stories follow a basic format: “As a [user], I want to [do something] so that I can [achieve a goal].” Example: “As a new customer, I want to check out as a guest so that I don’t have to create an account.”

These stories help designers and developers prioritize features, improve usability, and create intuitive experiences. Instead of guessing what users need, teams can rely on user stories—to an extent—to picture real-world scenarios and guide their decisions.

From focusing on user goals instead of technical details, user stories can help ensure that designs are practical, user-friendly, and aligned with business objectives.

Read our piece User Stories: As a [UX Designer] I want to [embrace Agile] so that [I can make my projects user-centered] for further insights about user stories.

Watch as UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains important points about user stories:

A good user story has three key components: the user, the action, and the goal. It should be clear, concise, and focused on solving a real problem.

User – Defines who the story is for. This should be a specific type of user, not just “the customer.” Example: “As a returning shopper...” instead of “As a user...”

Action – Describes what the user wants to do. This should be a single, meaningful task. Example: “...I want to save my payment details...”

Goal – Explains why the action matters. This ensures the feature has a clear purpose. Example: “...so that I can check out faster next time.”

So, a strong user story follows the format:

"As a [user], I want to [do something] so that I can [achieve a goal]."

This structure helps UX teams prioritize design decisions, improve usability, and create features that truly benefit users.

Watch as UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains important points about user stories:

Enjoy our Master Class How to Find User Insights Through Storytelling with Whitney Quesenbery, Director, Center for Civic Design.

User stories and use cases both describe user needs, but they serve different purposes.

A user story is a short, simple statement focusing on what a user wants to do and why. It follows the format: “As a [user], I want to [do something] so that I can [achieve a goal].” Example: “As a returning customer, I want to save my payment details so I can check out faster.”

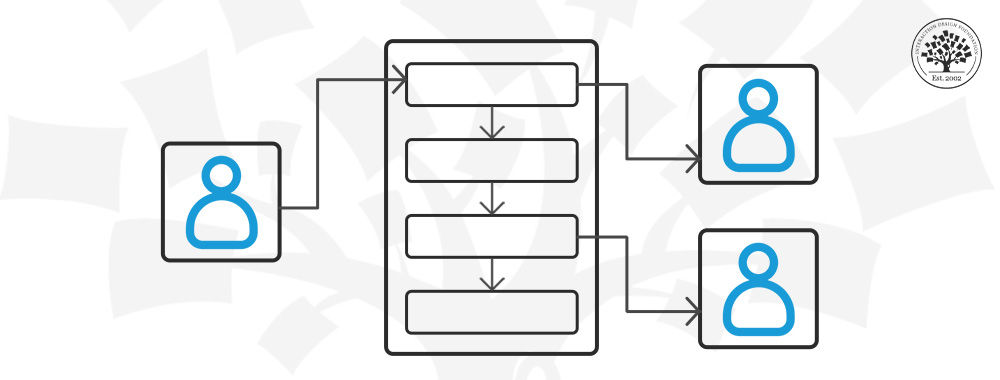

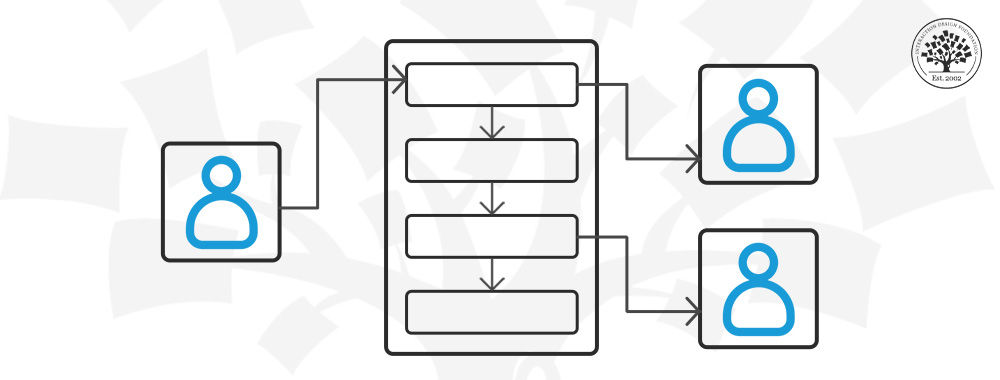

A use case is often more detailed (Agile versions of use cases start with minimal detail, like that of a user story). It outlines step-by-step interactions between the user and the system—including alternative paths and error handling. Example: A use case for checkout would list steps like “User enters payment details,” “System validates the card,” and “User confirms purchase.”

The key difference is that user stories focus on user goals in simple language, while use cases describe detailed workflows for developers and designers. Teams often start with user stories and expand them into use cases when they’re defining system behavior.

Watch as UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains important points about user stories:

User stories help UX designers stay focused on real user needs throughout the design process. They define what users want to achieve, which guides decisions from early sketches to final prototypes.

In the research phase, designers create user stories based on interviews, surveys, or observations. Example: “As a first-time user, I want a guided onboarding so I can quickly understand the app.” This helps designers identify key features.

During wireframing and prototyping, user stories shape layouts and interactions. From stepping into their users’ shoes, designers ensure screens align with user goals rather than just business needs.

In usability testing, teams validate whether the design truly helps users complete their tasks. If users struggle, designers refine the experience based on feedback.

By keeping the process user-centered, user stories help ensure the final design is both functional and intuitive. They help teams prioritize (needed) features, improve usability, and create experiences that solve real problems.

Watch as UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains important points about user stories:

To identify the right user needs for a user story, start by researching real users. Conduct interviews, surveys, and usability tests to understand their goals, frustrations, and behaviors. Focus on what users need to accomplish—not just what features they want.

Analyze patterns in user feedback to find common challenges. Example: If multiple users struggle with a long checkout process, their need may well be: “As a frequent shopper, I want a one-click checkout so I can buy faster.”

Use personas (fictitious representations of proposed users) to make sure the story reflects real users, not assumptions. In fact, persona stories are more effective because they provide context and emotional insight so you and your team can better understand user behavior, motivations, and pain points. These narratives put a “face” on the user and help humanize user needs beyond raw data. Persona stories inform user stories because they provide the “why,” while user stories provide the “how” and the actions needed to satisfy real user needs—as projected by the persona.

Once you define the need, write a clear, simple user story that connects to a real goal. The best user stories focus on specific tasks and benefits, helping designers create features that truly improve the experience.

Enjoy our Master Class User Stories Don't Help Users: Introducing Persona Stories with William Hudson, Consultant Editor and Author.

Common mistakes in writing user stories can make designs less effective and harder to implement. One big mistake is being too vague—a good user story should clearly define the user, action, and goal. Example of a weak story: “As a user, I want a better dashboard.” Instead, be specific: “As a sales manager, I want a dashboard that shows monthly revenue trends so I can track performance.”

Another mistake is focusing on features, not user needs. A user story should describe what the user wants to achieve, not just list functions.

Teams also run into trouble when they write stories which are too large—each one should focus on a single action. If it’s too broad, it’ll help nobody, so break it into smaller stories.

Last, but not least, ignoring real user research is a major “no-no.” Stories must come from actual user feedback and data-driven revelations about users, their user needs, user behavior, and real-world concerns. You may think you know all about your users, but you’ll need to test those assumptions with UX research. Otherwise, you’ll be basing your design foundations on the shaky ground of guesswork—and be in for a rude awakening when your design work gets to user testing.

Watch as UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains important points about user research:

Yes, stakeholders should be involved in writing user stories—but they shouldn’t write them alone. Their input helps ensure that business goals align with user needs. However, UX designers and product teams should refine stories to keep them user-focused.

Stakeholders—like product managers or marketing teams—provide valuable insights about business objectives, customer pain points, and industry requirements. Example: A customer support manager might highlight frequent complaints about a confusing checkout process, leading to a user story like: “As a shopper, I want a simple checkout so I can complete my purchase quickly.”

However, stakeholders sometimes push for features instead of user goals (e.g., “Add a chatbot” instead of “Help users find answers easily”). UX designers must reframe these requests into user-centered stories to keep on track, so nobody “jumps the gun” and assumptions solidify and suddenly intrude into the solution space.

So, effective communication and collaboration are vital. By working with stakeholders while keeping the focus on user needs, teams can create effective, goal-driven user stories that balance business and UX priorities.

Watch as Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach, Todd Zaki Warfel explains important points about how to present to clients:

Read our piece User Stories: As a [UX Designer] I want to [embrace Agile] so that [I can make my projects user-centered] for further insights about user stories.

Relying too much on user stories can lead to an incomplete or biased design process. While user stories help focus on user needs, they’ve got limitations that can create risks if teams don’t balance them with other UX research methods.

Lack of context – User stories are short and don’t always capture why users need a feature or how they behave in real life. Without research, teams might misinterpret needs. Example: “As a shopper, I want faster checkout.” But why? Is it because forms are too long, or because they don’t trust the payment process? It’s a good idea to create personas (fictitious users) to put a human “face” and a plausible “body” in the shoes of users to get behind the “why” aspect.

Too feature-focused – If teams only follow user stories, they might focus on individual features rather than the overall experience and user journey. Features that seem like great “essentials” at the time can become almost irrelevant “nice to haves” or even clutter or obstacles if the holistic experience proves they’re not so valuable.

Ignoring broader UX research – User stories should be backed by data from interviews, usability tests, and analytics. Relying only on the stories can result in designing for assumptions rather than real behavior—a recipe for design fails.

The best approach balances user stories with real-world research and testing.

Watch as Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Alan Dix explains important points about personas:

Enjoy our Master Class User Journey Mapping for Better UX with Kelly Jura, Vice-President, Brand & User Experience at ScreenPal

Lucassen, G., Dalpiaz, F., van der Werf, J. M. E. M., & Brinkkemper, S. (2016). Improving agile requirements: The quality user story framework and tool. In Requirements Engineering: Foundation for Software Quality (pp. 97–114). Springer.

This paper introduces the Quality User Story Framework, a structured approach to improving user stories in agile development. The authors identify common quality issues in user stories and propose a framework to assess and enhance their clarity, consistency, and completeness. The framework is supported by an automated tool that evaluates user stories based on predefined quality criteria. Through empirical evaluation, the study demonstrates that improving user story quality can significantly enhance requirement specifications and overall project success. The research provides a valuable contribution to UX design by ensuring user stories effectively capture user needs and system requirements.

Cohn, Mike. 2004. User Stories Applied: For Agile Software Development. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Mike Cohn provides a comprehensive guide to integrating user stories into agile development processes. While primarily focused on software development, the book offers valuable insights into understanding user needs and crafting user stories that inform design decisions, which is essential for UX professionals aiming to create user-centered designs.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on User Stories by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into User Stories with our course Object-Oriented UI Design: Build Interfaces Users Love .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your expert for this course:

William Hudson: User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!