How to overcome Fixation and Bias in Creative Problem Solving

- 447 shares

- 4 years ago

Fixation is the human tendency to approach a given problem in a set way that limits one’s ability to shift to a new approach to that problem. As such, fixation impairs ideation for designers and results in impasses. It can also cause the Einstellung effect, the phenomenon of overlooking better ways of solving problems.

“Fixation is the way to death. Fluidity is the way to life.”

— Miyamoto Musashi, Strategist, philosopher, writer and founder of a swordsmanship style

See how fixation happens, what it causes and how a matchbox and candle become part of an unexpected solution:

You've probably all had some problem you've worked at. And you keep going at it, and you keep going at it... Nothing seems to work. You go away. Suddenly, the next day you think, 'What problem? It's easy!' It's something I said I've certainly had, and I'm sure you've encountered. And psychologists and other people studying creativity have looked at these kind of

issues – why it is that we get to these impasses and how it is that we break out of them. *Fixation* is one of the keywords that psychologists use here: the way in which when you start to deal with a problem, you have some sort of approach, some sort of way of dealing with it, and it's incredibly hard to stop just continuing with that same way. Once you've got that original idea, that original approach, it's very hard to go to a new one.

And sometimes – you know – an approach that might work for one problem doesn't work for another, but of course if you're stuck in that approach, you can't try other ones. This can get worse depending on how you encounter the problem. And this is sometimes used in sort of trick questions to get you thinking down the wrong track and then it's very hard to get down the right one. And this is sometimes called – if I can say it right! – the *Einstellung effect*

which is about being fixed in a position. These guys called Luchins and Luchins back – I think – in the 1940s did experiments with water jars. And you've probably seen this sort of puzzle. You've got a number of jars, and the idea is they're different sizes and you're trying to get, say... two pints of water and you've got a 17-pint jug and a 3-pint jug and you've got to pour water back and forth. And there sometimes are really complicated solutions where you have to like fill one up

from another, and then what's left in this one is some nice magic amount. So, if you've got a 3-liter jug and a 7-liter jug and you fill the 7-liter one and you pour it into the 3-liter jug and then throw the three liters away, you've got four liters in your 7-liter jug. And you have these complex solutions. So, what Luchins and Luchins did was they gave people a number of examples which they worked through which required that kind of complex solution. And then they gave them four more. But the four more they gave them were ones where you could

actually solve it very, very simply. You know – possibly just filling up two and pouring them into another. So, some subjects were given that; some were just given the four easy problems. The ones who were just given the four easy problems solved it in the easy way. The ones who *started off with the complex ones applied the same complex heuristics* to the easier problems and took *much longer* to do it. So, they got so stuck in their ways, having been introduced to this set of problems.

One that I encountered myself, and this gives you an opportunity to laugh at me if you want to, because you'll probably, most of you I'm guessing might find this easy, but I was in university and I was once given this puzzle. And the puzzle starts off – and there is this stage where you're driven down the wrong path – anyway, so I'm giving you a hint by telling you that. So, you often get these puzzles where you're supposed to chop things up into identical pieces. So, I've got a square up there, and obviously you can chop a square into four identical

smaller squares. Or you can chop it into four triangles. So, the triangles are all the same shape as each other, the same size as each other. In mathematical terms, they are *congruent to* each other. But they're not necessarily squares. I've got some triangles, and we can chop the triangles into four; they're different kinds of triangles in different ways. And on the right I've got one of the ones you sometimes see as a trick puzzle in books; and – or sometimes actually cut out pieces as a sort of trivia-type puzzle.

And the idea there is to have four pieces that will make up that 'L' shape. And certainly there may be other ways of doing it, but the way I've always seen is with these four pieces like that. So, they're all 'L' shapes themselves and they fit together. How about cutting things into three? Well, obviously, the 'L' shape is an easy one, and things that start off with three degrees of similarity like a triangle or hexagon are relatively straightforward.

So, the crucial question is, can you chop a square into three pieces that are congruent with one another? Not all squares, but some shape – they could be triangular; they could be more complex – that are each identical. Can you do it? Now, my guess is you've probably already thought of how to do it and you'll be right. It took me three days to solve this because I was a mathematician

and the whole thing was framed in geometry, mathematics, and I was trying to apply really complex mathematics. And despite numerous hints, it took me three days to solve this. If you haven't solved it, you're probably a budding mathematician. So, *fixation is a problem*. There's also – fixation is more about the methods you use to apply things, but there's also *bias* – when you *evaluate* things. When we look at them, we have

tendencies to see things in one way or another. And that's about all sorts of things. That can be about serious personal issues. It can be about trivial things. Often, the way in which something is *framed* to us can actually create a *bias* as well. A classic example, and there are various ways you can do this, is what's called *anchoring*. So... if we're asked something and given something that *suggests a value* even if it's told that it's just there for guesswork purposes or something,

it tends to hold us and move where we see our estimate. So, you ask somebody, 'How high is the Eiffel Tower?' You might have a vague idea that it's big, but you probably don't know exactly how high. You might ask one set of people and give them a scale and say, 'Put it on this scale. Just draw a cross where you think on this scale, from 250 meters high to 2,500 meters high, how high on that scale?

And people put crosses on the scale – you can see where they were, or put a number. But alternatively, you might give people, instead of having a scale of 250 meters to 2,500 meters, you might give them a scale between 50 meters and 500 meters. Now, actually the Eiffel Tower falls on both of those scales: the actual height's around 300 meters. But what you find is people don't know the answer; given the larger, higher scale, they will tend to put something that is larger and higher

even though they're told it's just a scale. And, actually, on the larger scale it should be right at the bottom. Here it should be about two thirds of the way up the scale. But what happens is – by framing it with big numbers, people tend to guess a bigger number. If you frame it with smaller numbers, people guess a smaller number. *They're anchored by the nature of the way the question is posed.* So, how might you get away from some of this fixation? We'll talk about some other things later, other ways later.

But one of the ways to actually break some of these biases and fixations is to *deliberately mix things up*. So, what you might do is, say you're given the problem of building the Eiffel Tower. And the Eiffel Tower I said is about 300 meters tall, so about a thousand feet tall. So, you might think, 'Oh crumbs! How are we going to build this?' So, one thing you might do is say, 'Imagine, instead of being 300 meters tall, it was just *three* meters tall. How would I go about building it, then?'

And you might think, 'Well, I'd build a big, perhaps a scaffolding or 30 meters tall. I might build a scaffolding and just hoist things up to the top.' So, then you say, 'Well, OK, can I build a scaffolding at 300 meters? Does that make sense?' Alternatively, you might, say, perhaps it's *300,000 miles tall* – basically reaching as high as the Moon. How might you build that now? Well, there's no way you're going to hoist things up a scaffold – all the workers at the top would have no oxygen because they'd be above the atmosphere.

So, you might then think about hoisting it up from the bottom, building it, building the top first, hoisting the whole thing up, building the next layer, hoisting the whole thing up, building the next layer. You know... like jacking a car and then sticking bits underneath. So, *by just thinking of a completely different scale*, you start to think of *different kinds* of *solutions*. It forces you out of that fixation. You might *just swap things around*. I mean, this works quite well if you're worried about

– that you're using some sort of racial or gender bias; you just swap the genders of the people involved in a story or swap their ethnic background, and often the way you look at the story differently might tell you something about some of the biases you bring to it. In politics, if you hear a statement from a politician and you either react positively or negatively to it, it might be worth just thinking what you'd imagine if that statement came to the mouth of another politician that was of a different persuasion; how would you read it then?

And it's not that you change your views drastically by doing this, but it helps you to perhaps expose why you view these things differently, and some of that might be valid reasons; sometimes you might think, 'Actually, I need to rethink some of the ways I'm working.' So, back to the theory now. Psychologists, I said, and people studying the cognitive aspects of creativity talk about *insight problems*.

And fixation is an aspect of insight problems. Some problems you can just start at the beginning and work your way through, and so long as you work enough, you get an answer out. Sometimes you can do it faster or slower... and you might be lucky in that you approach it and perhaps the first thing you try works. You know – and you might go to a maze and you might just say, 'Well, first of all I'll try the right-hand side. And if that doesn't work, I'll come back and then I'll turn to the left, try the left-hand side.'

You can work your way through. But some problems aren't like that. No matter how hard you keep working at them, you can't solve them. You need some little spark, this bright idea, this different approach to come from a different direction in order to solve it. Now, that happens at a big scale with big problems, but also there are quite small-scale problems. And for experimentation purposes, psychologists often use these, give them to people and then perhaps try and manipulate things, perhaps use suggestive words,

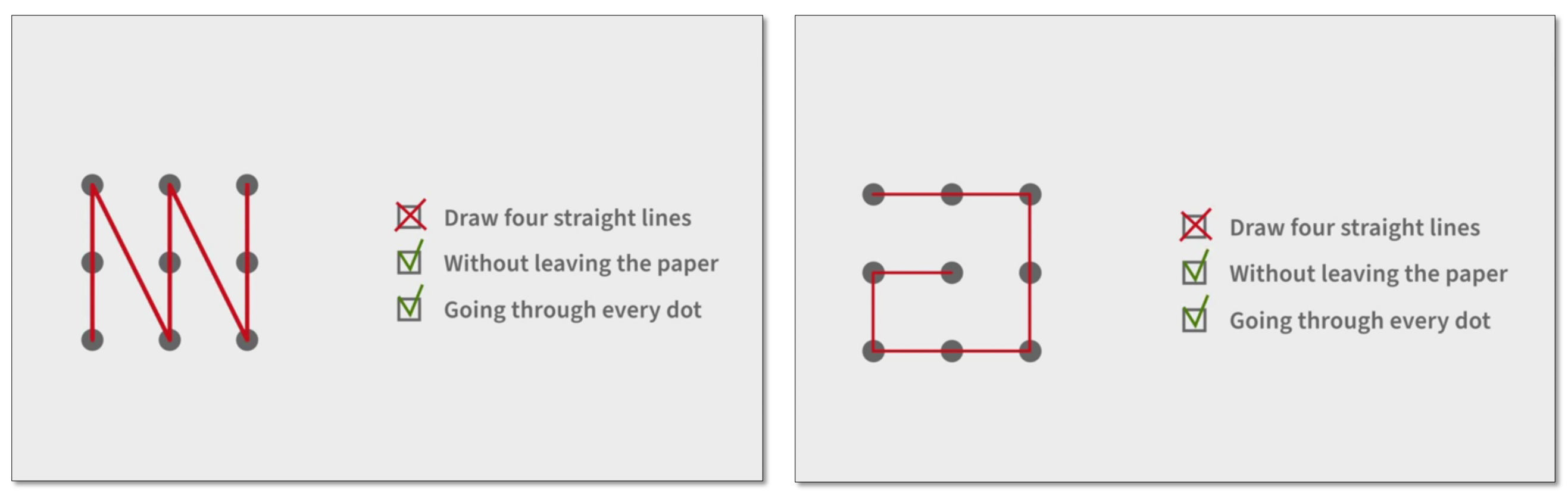

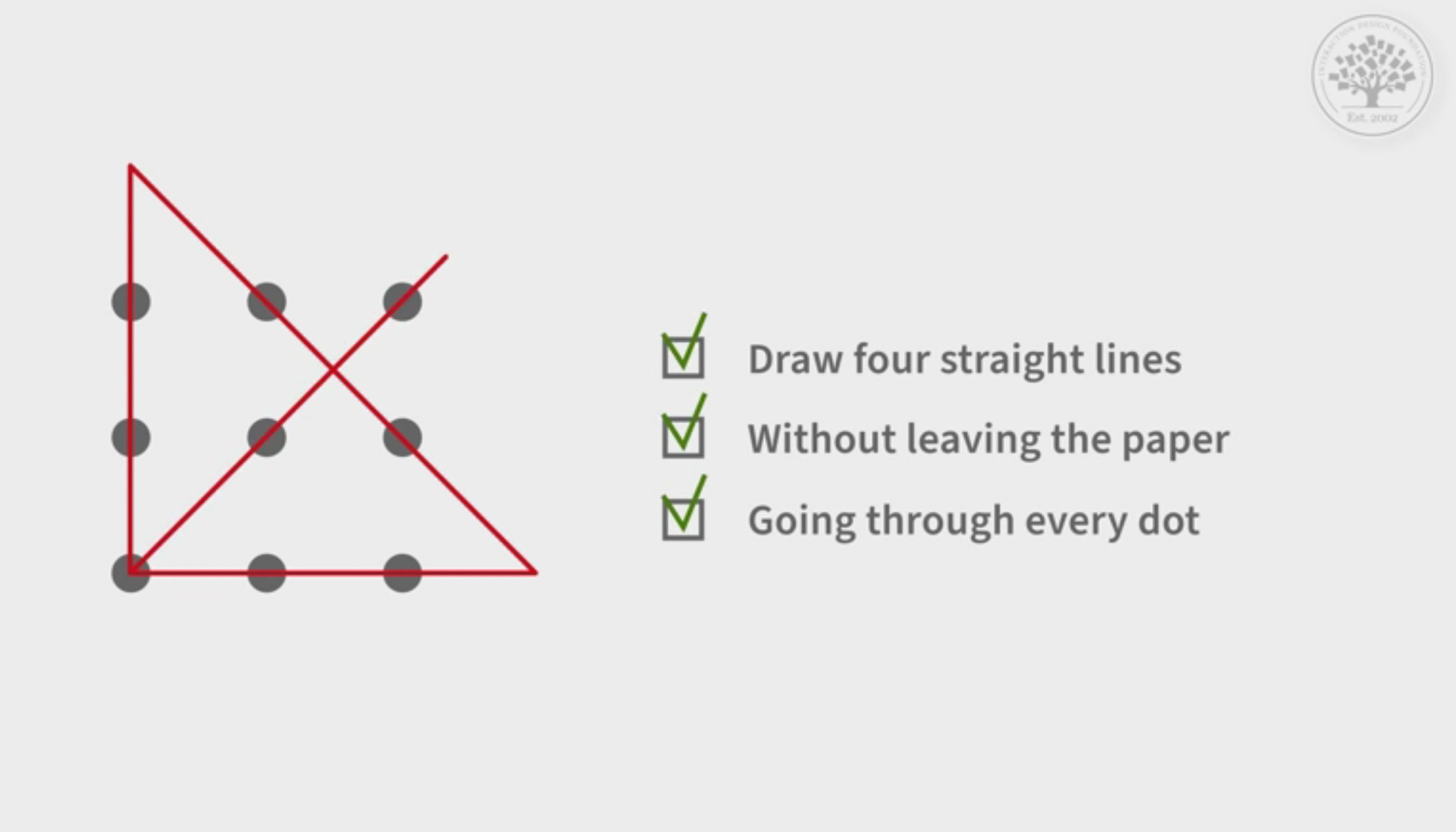

do different things to help understand what might change that. Here's a couple of examples; so, the first one is a more geometric one. And this is again often used in experimentation. So, what you have is – you might have seen it and you might know the solution, but you have three lines or three dots equally spaced. And your job is to try and have four straight lines, but where as you draw them you're not allowed to lift your hand from the paper. So, and the straight lines have to go through – every dot has to have a line going through it.

Now, you're allowed to have two lines going through the same dot, but every dot has to have at least one line. So, you can see that if you didn't have to lift your hand off the paper, you could easily do it with three lines – just go one, two, three, or one, two three. Or, if you keep on the paper, you could go up, down, like do a sort of diagonal through, zigzag through, and you could do it very easily with five lines. Or, you could perhaps go around the edge and into the middle – try it.

Five lines is easy without leaving the paper. Three lines is easy, so long as you're allowed to leave the paper. The problem is to do four straight lines and you're not allowed to leave the paper. I'll come back and give a solution to that later; I'll warn you before I do. But you might want to have a think about that as a problem if you've not come across it before. So, I'm going to give you another problem now, which is *the candle in the cellar problem*. So, you're going into a dark cellar and you are given a candle,

some drawing pins, or sometimes just one drawing pin – if I can get one out of the box here. So, it's just a single drawing pin, but sometimes you're given several. And a box of matches – probably smaller than this, usually, is the example one, but a box of matches. And you're then given a bit of a story that you're going to have to use both your hands to lift something out of the cellar. But it's really dark, so you need the candle to (have) light, but you can't just hold the candle.

And I'll give you *the solution* to this now, and there's a standard solution. And this is interesting as an insight problem. But we'll come back to that in a bit. One of the standard solutions, or the standard solution perhaps, is to – and I won't empty them all out, because there's a lot of them, but – oh – I've got a smaller match box, I've just realized, inside my bigger match box – is that you basically take out the tray and use the tray as a support for your candle

and then pin the tray to something. Obviously that depends on there being something to pin the tray to, the cardboard tray to hold the candle without it falling off. I'd probably want to try and find an angle to put it into. But, anyway, there are solutions. What you find, though, is in order to have that solution, you have to stop thinking about this as a box that contains a match to light the candle. So, you actually have to think of the box as being something you can use to mechanically solve the problem;

because what people typically do is they start off thinking of lots of ways of trying to use pins to support the candle because pins are for joining things; pins are for connecting things; you want to connect the candle some way to a wall or someplace to support it. And you have to stop thinking of this as the way to light the candle and think of this as the way to *support* the candle. So, a different way of thinking – so that's one standard way. The thing with these insight problems is you have to *change your way of thinking*;

you can't just follow the way you were doing it before. The psychologists talk about *incubation*, so what happens – you're trying to solve a problem like this, but often – and you'll have found it yourself – you go away, sometimes go to sleep and wake up the next day; if you're doing an experiment, they usually just get somebody to do some other tasks for a while that eats up their mind, and then return to the problem again. And very often when you return to the problem, you just think, 'Ah! Of course!'

(Sound effect) And it comes out. And this is *incubation followed by insight* actually. So, you have the problem and then after the incubation often this insight just happens in a way that doesn't if you keep on working at the problem. I said you've have probably encountered this yourself, both for big-scale problems and also this more puzzly kind of problem. So, how does this work? And here the jury is a little bit more out.

It's well understood that this happens. It's less well understood, but... there are lots of works... there is a lot of understanding. But it's still less well understood *exactly* how it happens. Some of it is clearly just about the fact that you let the problem out of your mind, but you know what the problem is, so you don't have to get it explained again. And of course, the *very explaining of the problem* *may create the fixation*.

So, for instance... as soon as you see the candle and the matches, you instantly think 'candles to light, match'; whereas when you come back to it, you don't have to think that, because you just know it's the problem. So, sometimes it's about getting out of your mind and then your mind is fresh. The solution strategies you were following of course are so much in your mind when you're doing it the first time, you can't think of anything else; whereas when you come back to it, suddenly there's a possibility of thinking a new way – you're breaking the fixation purely by not being there and then coming back to it.

There's also quite a lot of discussion about how much happens *unconsciously* during this incubation period. And the debates on this – they're clearly things do happen, that you're in a better position to solve the problem often when you come to it later than before. Why that is is interesting. There are some famous things about this; like the guy who discovered benzene rings.

He was trying to work out how on earth their carbon and hydrogen atoms fitted together. And one of the various stories that are related is that he imagined these – sometimes it's snakes swallowing each other or people dancing with each other hand to hand – and then actually does this sort of half asleep and then wakes up and thinks, 'Aha!' And one way of looking at that is to say that his unconscious mind was going through all the problem and actually had found the solution, was telling him through his dreams.

Another way to think about this is that actually, of course, especially if your mind is wandering, various thoughts come along; you have a problem sitting there. If one of those thoughts happens to sort of, say, match the problem, you think, 'Aha! I've got it!' So, again, that guy probably woke up a dozen times or dozens of times with all sorts of half dreams in his head, most of which were completely irrelevant.

When he wakes up with the one that *is* relevant, of course it suddenly matches the problem and he sees the solution. So, it's not clear whether it's random, whether it's thinking in your unconscious. But what is well understood is that this makes a difference. So, again from a practical point of view, doing this is something you do, making sure you have these breaks when you get stuck. So, I'll just give you the dots one. One of the nice things about this dots example, it is *literally about thinking out of the box*,

because the dots create a box and what happens is certainly a lot of people tend to try and draw the lines often starting at the dots. The other thing is, how do you draw a line when you've got dots? You naturally tend to think of starting on a dot and ending on a dot. As soon as you allow your lines to escape the box, and – I was supposed to warn you before, so hopefully you've noticed this if you wanted to think about it;

if not, stop me now and go off and think more. But if you start to think *outside the box*, suddenly solutions come. Here is the canonical solution. So, you start at the bottom corner; you go *outside* the box, and then cut diagonally across, so it's almost like there's an extra dot at the outside. And this is weird. If you added dots, this gets easier; it's one where you add dots, suddenly the problem gets easier. Then you come back down to that bottom left-hand corner, and then you take yourself back out again,

and you've gone through all the dots – four straight lines, pencil never left the paper. So, it's interesting. Now I do know that one well. But there's quite a few times where I saw that and thought 'Oh, that's clever!' and then came to it later and found I'd actually forgotten that solution and got stuck in exactly the same way as I had before. But you notice here, there's a lot of assumptions that you bring to a problem, like the fact that lines perhaps start and end on dots might be one of the ones that was

going through your head and stopping you thinking about some of these solutions.

Humans are hard-wired to jump to conclusions, often without realizing we do so. For example, the principle of Occam’s Razor describes how the simplest explanation is usually the correct one – and captures our distrust of convoluted answers. Having such straightforward ways of seeing things is comforting in an ever-changing world. It helps people make sense of new situations far more easily than treating each as an entirely new phenomenon and adopting a beginner’s mind to decode it.

However, design is the wrong setting for this tendency, and fixation is one aspect—or symptom—of insight problems. Fixation is also possibly the most obstructive force in a design process, and “traditional” or “standard” approaches to certain situations can lock designers into a “box” where there’s no clear view of what a new problem truly involves. The first goal is to understand the users’ situation thoroughly; the second is to define/frame the problem accurately – which often means using disruptive tactics such as outside-the-box thinking. Since design problems tend to be complex and successful designs are both useful and novel, it’s vital to be able to stretch beyond existing ways of seeing users, their contexts and their problems. So, innovative designs are not ones you can pull from “the shelf” (i.e., your existing understanding). It usually takes shattering that old frame of reference to get a real grasp of what’s involved.

For example, consider the problem of drawing four straight lines through a nine-dot square without leaving the page.

The two attempts above show how people might approach this problem, which demands—literally—going outside the box (below).

Some great ways to avoid/minimize fixation are:

Trust in the Freedom of Scope which a Problem Permits – As opposed to trusting your (or a team-mate’s) initial interpretation of that problem. Bias can creep in all too easily and trap your perspective. The Einstellung effect can also kick in if someone suggests the problem involves factors which aren’t present. Also, the way the problem is explained can itself create fixation, and if a problem statement has the wrong wording or view of your users, the anchoring effect can push your team down the wrong avenues looking for a solution.

Use Out-of-the-Box Thinking – When your problem isn’t “cooperating” with you, push beyond the edges of the design space. Use methods such as brainstorming to work towards a spark of a bright idea.

Stop thinking of Items as having Limited, Dictionary-definition Uses – In our video example, a matchbox serves as a candle holder. You can adapt this concept almost limitlessly by looking beyond the predefined qualities or affordances of anything you might leverage to tackle a problem. Complex problems demand resourcefulness in defining what objects/features get used for.

Believe in the Power of Incubation – To overcome an impasse, stop spinning your wheels. Just follow the stages of creativity and leave the problem so you can return with a fresh view. When you come back, that “Aha!” moment of lightning-bolt-inspired insight may have already struck. Leave it to your subconscious – it’s one of the hardest-working allies you may never get to know.

Beware of Topic Fixation in Ideation Sessions – Your design team may start becoming less receptive to other lines of thinking if several dominant ideas surface, especially early on. This can be hard to spot and manage, and more extroverted or outspoken team-mates may guide the threads of discussion down these narrow alleyways. The risk is everyone will tacitly accept these as the likeliest pathways to the best solutions rather than limiting factors of fixation – and shut off from considering other, better ways forward.

Remember, Old Solutions were once Novel Ones which Innovators found for Their Own, Unique Problems – It’s natural for our minds to try for comparisons as convenient yardsticks to measure with. A popular strategy in documentaries, etc., is to use analogies to make old concepts more relevant to modern audiences. However, a risk of bridging to earlier ideas is overlooking some insights and contemporary factors – e.g., the Inca Trail as “the Internet of the time” (early 1500s). So, while analogies to other situations/problems might be helpful, understand the limitations of old solutions vis-à-vis your problem’s uniqueness. A good remedy is to try pushing the boundaries in a new direction using divergent thinking methods such as random metaphors.

Overall, remember that fixation is about framing. Only you can control how you approach finding, defining and starting to search for solutions to your users’ exact problems.

© Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

Take our Creativity course, addressing fixation.

Do you all have those moments when you know you need a spark of creativity? You know... "I want my wonderful bright idea!" — — Nothing comes. I'm not going to try and give you a creativity machine; so, what I'm going to try to do is give you *techniques* and *mechanisms*. I hope that wasn't too shocking for you, seeing me waking up in the morning!

You notice what I'm trying to do here is to make the *maximum* use of the *fluid* creative thinking and yet also then translate that and make it into something that's more structured. And this is true whether it's producing a piece of writing, producing a presentation or video or producing some software.

Get on and *do* it!

Fast Company incisively addresses fixation and offers many helpful tips.

This workshop account explores design fixation extensively.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Fixation in UX/UI Design by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Fixation with our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services .

The overall goal of this course is to help you design better products, services and experiences by helping you and your team develop innovative and useful solutions. You’ll learn a human-focused, creative design process.

We’re going to show you what creativity is as well as a wealth of ideation methods―both for generating new ideas and for developing your ideas further. You’ll learn skills and step-by-step methods you can use throughout the entire creative process. We’ll supply you with lots of templates and guides so by the end of the course you’ll have lots of hands-on methods you can use for your and your team’s ideation sessions. You’re also going to learn how to plan and time-manage a creative process effectively.

Most of us need to be creative in our work regardless of if we design user interfaces, write content for a website, work out appropriate workflows for an organization or program new algorithms for system backend. However, we all get those times when the creative step, which we so desperately need, simply does not come. That can seem scary—but trust us when we say that anyone can learn how to be creative on demand. This course will teach you ways to break the impasse of the empty page. We'll teach you methods which will help you find novel and useful solutions to a particular problem, be it in interaction design, graphics, code or something completely different. It’s not a magic creativity machine, but when you learn to put yourself in this creative mental state, new and exciting things will happen.

In the “Build Your Portfolio: Ideation Project”, you’ll find a series of practical exercises which together form a complete ideation project so you can get your hands dirty right away. If you want to complete these optional exercises, you will get hands-on experience with the methods you learn and in the process you’ll create a case study for your portfolio which you can show your future employer or freelance customers.

Your instructor is Alan Dix. He’s a creativity expert, professor and co-author of the most popular and impactful textbook in the field of Human-Computer Interaction. Alan has worked with creativity for the last 30+ years, and he’ll teach you his favorite techniques as well as show you how to make room for creativity in your everyday work and life.

You earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you’ve completed the course. You can highlight it on your resume, your LinkedIn profile or your website.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!