Workshops to Establish Empathy and Understanding from User Research Results

- 676 shares

- 5 years ago

Workshops in user experience (UX) design are intensive collaborative sessions where teams solve problems and enable progress on certain challenges throughout the design timeline. A facilitator directs participants for a period of focused idea generation and hands-on activities that let them reach actionable goals optimally.

Service Designer at Booz Allen Hamilton, David Bill explains how to use workshops to engage stakeholders:

The primary purpose of a UX workshop is to solve a problem, develop a plan or reach a decision. These sessions are focused on a limited range of problems—and they let teams get to actionable goals and make detailed roadmaps for achieving them. Participants meet as a group to engage in various activities—from brainstorming ideas to role-playing user scenarios—and work to optimize the digital products, user interactions and user experience concerned, while maximizing business goals.

UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains brainstorming:

UX workshops come in many forms. Each has its own set of goals and techniques. From design thinking sessions to prioritization exercises, these workshops help teams build empathy, generate ideas and make informed decisions.

William Hudson explains design thinking in this video:

UX workshops offer several advantages for design teams, brands and the users they serve:

UX workshops bring together diverse perspectives to create better design solutions. Workshops encourage cross-functional collaboration: Designers, developers, product managers and even end-users work together.

UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains important points about cross-functional collaboration:

In a UX design workshop, ideas can arise easily when everyone feels encouraged to contribute their insights. Workshops often go through a series of diverge-and-converge sequences, as teams produce many ideas and then identify patterns and themes within them.

Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains important points about divergent and convergent thinking:

UX design workshop activities focus tightly on solving specific problems or challenges. This concentrated time allows for rapid idea generation and hands-on activities.

This iterative approach is more likely to result in a successful product or service—one that accounts for user behaviors and truly meets the needs of its users. For example, workshops make use of prototyping techniques—that’s so participants can quickly test out ideas to see if it’s worth pursuing ideas.

Professor Alan Dix explains prototyping and why it’s important:

UX workshops also play a crucial role in validating ideas—a chance to use data and user feedback as the basis for activities and discussions. It’s something that helps teams make sure their solutions can address real user problems as they can:

Find gaps and pain points: Discuss problematic areas that don't fit user journeys.

Define an MVP (Minimum Viable Product): Collectively define high-level values by grouping themes in user stories.

Manage risks and expectations: Establish vital strategic steps on the way towards a favorable outcome.

Discover scenario triggers and outcomes: Determine key user tasks that haven’t come up in the user personas.

Prioritize user needs: Establish the most important user needs through argumentation.

Laura Klein explains important points about MVPs:

It’s crucial to build empathy for users in UX workshops. These sessions often involve activities that help participants better understand and connect with the end-users of their products or services.

See why empathy is a vital ingredient in design:

One effective technique is empathy mapping, which helps characterize target users to make effective design decisions. Here, groups externalize their knowledge about customer segments and key defining characteristics of each type. Another valuable tool is user journey mapping. When participants work on building a user journey map or a customer journey map, they deconstruct a user's experience with a product or service—working it back into a series of steps and themes. This process helps them find potential opportunities for the product roadmap and encourages participants to think in terms of users and journeys, rather than specs and features.

CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers explains journey mapping from a service design perspective:

This customer journey map reflects the experience of a fictitious customer and can present vital points to workshop participants.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

UX design workshops come in various forms and each serves a specific purpose in the design process. Here are some examples:

Discovery workshops are the stepping stones to better understand a product and collect information to begin a project. In these, users get involved—and share their perspectives on how a potential project might benefit them. They typically occur when there's a need to:

Understand existing research and stakeholder expectations.

Build a common understanding of project direction and vision.

Minimize the risk of building the wrong thing.

Define what sets the product apart in the market.

These workshops help simplify complex projects. A structured roadmap and clear requirements that align with goals will ideally result. They usually last 2 to 4 days, but it depends on the project scope.

© NN/g, Fair Use

Empathy workshops help teams understand and prioritize user needs before they move on to design a solution. They aim to:

Get clarity and consensus on user needs, motivations and behaviors.

Build empathy for users.

Shift stakeholder perspectives from a features-first mindset to a user-first one.

These workshops often involve creating user personas—semi-fictional characters representing the needs of larger user groups so teams can empathize with their target audience and make more informed design decisions.

© NN/g, Fair Use

Professor Alan Dix explains important points about personas:

Also called design-studio workshops, in these sessions teams focus on rapidly generating and discussing a wide set of ideas. Namely, participants:

Use idea-generation activities like sketching and out-of-the-box thinking to encourage discussion.

Professor Alan Dix explains what out-of-the-box thinking involves:

Incorporate cross-disciplinary perspectives—to get more well-rounded views overall.

Create shared ownership in project success through co-creation activities.

© NN/g, Fair Use

In these, users can help assess the impact of design ideas on user experience and complement the technical expertise of developers. Prioritization workshops help build consensus on which features customers or stakeholders value most. They're beneficial when:

There are too many competing priorities.

Stakeholders are asking for too much, which leads to scope creep.

Teams need to weigh the value of planned feature releases against each other.

Various methods are useful in these. Dot voting is one example. However, it's crucial to establish clear selection criteria to make sure that objective decision-making is a reality.

© NN/g, Fair Use

Critique workshops provide space in the design process to align design decisions with user needs. They help teams:

Evaluate existing content or designs with user needs as a lens.

Rapidly identify quick fixes for optimization.

Note necessary long-term evolutions or optimizations.

These workshops are useful checkpoints before new design projects begin or during intermittent design reviews. They let teams discuss user flow through a design and hear perspectives from different expertise areas.

© NN/g, Fair Use

Successful UX workshops start with a well-defined purpose. The facilitator should articulate the workshop's goal and make a structured agenda to guide participants toward that outcome.

Something that the success of a UX workshop heavily depends on is to have the right people in the room. That’s why it's crucial to invite a diverse group of participants—including decision-makers, independent contributors and user representatives. Still, it's important to strike a balance and avoid overcrowding the session—it’s not a case of the more the merrier.

UX workshops thrive on interactive and collaborative activities, which can include, for example, storyboarding. There, participants expand specific ideas and add context.

A skilled facilitator is crucial to guide the workshop and keep it focused on the end goal. Ideally a facilitator should be an active listener—someone who’s fully present in the proceedings. They must be an avid observer, too, since they’ll need to pick up on cues like body language. The facilitator's role includes to:

Explain activities clearly—and help keep everyone on track with what the aim is for each activity and the expectations involved.

Manage time effectively—which includes that they plan ahead to make sure there are set time slots for each activity and be flexible to accommodate short breaks and other things.

Encourage equal participation—so everyone can speak up.

Help the group navigate roadblocks—and, for example, help visualize ideas in real time.

Maintain neutrality and objectivity—and help participants see the value of understanding different viewpoints from everyone involved.

Ideally, the facilitator should focus just on guiding the process rather than participate in the activities themselves. It also takes some skill to be adaptable and be prepared to adjust plans and pivot when they need to. What’s more, it can take some diplomatic skills to quickly step in and resolve any conflicts or disagreements that may arise.

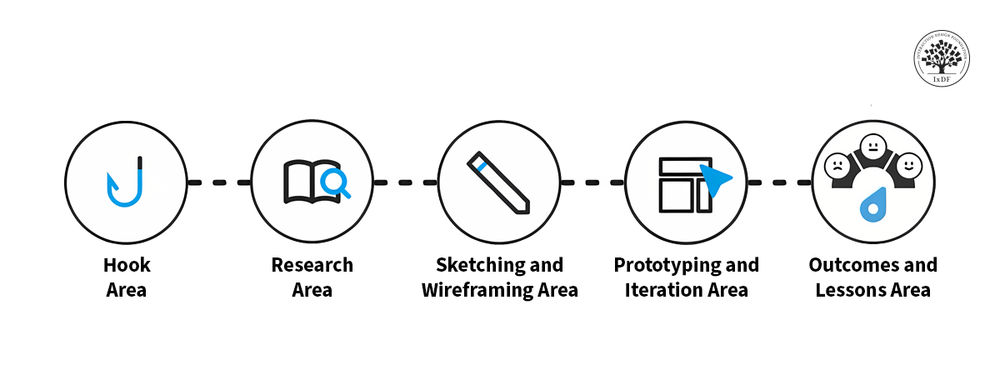

Facilitators and participants can benefit from a design thinking approach in workshops.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

The ultimate sign of effective UX workshops is that they end with clear, actionable outcomes—with the users firmly in mind.

Some common UX workshop activities include:

Brainstorming is a cornerstone of UX workshops, allowing teams to generate a wide range of ideas quickly and think laterally to examine the “ideascape” around them.

Professor Alan Dix explains lateral thinking and its uses:

After teams generate ideas, they often use affinity diagrams to organize and make sense of the information. They cluster related ideas into groups based on themes and similarities—to find patterns and recurring topics across the group, making it easier to prioritize ideas and find common ground.

Watch our video on affinity diagrams to understand more:

Prototyping is crucial for testing ideas and getting early user feedback. UX workshops often include activities that let teams create low-fidelity prototypes and more. These prototyping exercises help teams quickly iterate on designs and validate assumptions before deciding on making that investment in full development.

First, it’s important to point out that UX workshops can be in-person or remote. Both have their pros and cons, but a mindful facilitator can arrange to make the best of any workshop.

Set expectations: Facilitators should establish guidelines for communication, especially in remote settings. This includes that they should clarify how participants can contribute. For instance, they might use chat functions or specific gestures to indicate they’ve got something to say. These rules help keep communication respectful and collaboration smooth.

Set objectives: Workshop facilitators should set clear goals to determine the workshop type and structure. It's also important to consider where the team is in the UX design process, as this influences the workshop's focus.

Choose activities: These should be in line with the workshop's goals—and help participants generate ideas, solve problems or make decisions. It's vital to give enough time for each—and that includes breaks to prevent fatigue.

Prepare materials: It's important to secure all the needed materials—items like sticky notes, pens and whiteboards. For remote participants, make sure that conference calls and screen sharing tools are all set up and tested beforehand.

Icebreakers play a crucial role in getting people ready—and these activities help people feel connected, engage in conversation and relax before they dive into complex topics. From there, the facilitator and the group work to get the best results.

Personas are effective tools to keep ideation on track throughout workshops.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

The work doesn't end when the workshop does. It's crucial to plan follow-up actions. This might mean to translate workshop notes into a more practical format—like a report or visual representation. It’s vital to set a deadline for getting back to attendees about next steps and make sure they know about this during the workshop. To keep a healthy momentum, share workshop write-ups in an open format and invite further comments and ideas.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

For designers, a well-crafted UX portfolio is a passport to a world of design opportunities, including contracts from the most prestigious brands and clients.

Design Director at Societe Generale CIB, Morgane Peng explains important aspects about portfolios:

One by-product of effective UX workshops is how designers can include the work within them as case studies. Workshops can provide powerful evidence for how a designer collaborates and helps produce highly effective solutions. It’s vital to include not just the end result of the workshop, but all the important steps that led to it. That includes the methods and reasons—and how the designer contributed. What’s more, a storytelling approach can help shape case studies into powerful testaments to a designer’s capabilities and more.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Several issues can arise in a UX workshop, and it takes an attentive, diplomatic and proactive facilitator to:

Dominant participants can be annoying and disruptive—worst of all, they might “drown out” other participants’ good ideas or keep others from even bothering to talk. Some ways to address this are that facilitators can:

Refocus dominating participants toward shared goals, encouraging them to contribute more effectively to the group purpose.

Invite and encourage other participants to contribute, balancing the voice of the dominator.

Partly because of dominant personalities, but also because introverts may struggle with active participation in group settings, anyway, it’s important to encourage the latter’s involvement. The only way to make sure everyone talks is to make sure the atmosphere is comfortable for even the quietest participants to speak.

Scope creep happens when project deliverables or features swell up beyond what was originally agreed upon, without anyone adjusting the schedule or budget. To mitigate this, facilitators can do several things, such as to:

Clearly define the project scope from the beginning, involving the project team to gain buy-in.

Create a change management plan that outlines how to handle scope changes.

It can be hard to keep participants engaged and energized throughout a workshop. Some ways to help with this are to include breaks and allow time for participants to digest information and be creative. Plus, it can help to ask them for feedback before each break to gauge participants' thoughts and adjust the agenda if necessary.

Overall, it’s vital to remember that UX workshops aren’t just about generating ideas—they're about turning those ideas into actionable plans that lead to better user experiences. That’s the main quality that distinguishes them from meetings. With a clear structure, a keen and mindful facilitator, an atmosphere of inclusivity, as well as a group of participants who feel safe and on board with the proceedings, these workshops can help good ideas germinate. Better than that, they can blossom into impressive specimens of actionable design decisions—and the results these can flourish as measurable outcomes.

Our course Build a Standout UX/UI Portfolio: Land Your Dream Job with Design Director at Societe Generale CIB, Morgane Peng provides a precious cache of details and tips for freelancers.

Read our piece, How to Write Great Case Studies for Your UX Design Portfolio for valuable additional insights.

Look at our piece, Workshops to Establish Empathy and Understanding from User Research Results for more.

Read our piece, How to Create a Perspective Grid for additional helpful insights.

Go to 5 UX Workshops and When to Use Them: A Cheat Sheet by Kate Kaplan for further insights and tips.

See How to Plan a Workshop: A Quick and Easy Guide by Jack O’Donoghue for additional helpful details.

Check out The process and benefits of organizing a UX workshop by Adam Fard for more points that can help with workshops.

A typical UX workshop for a brand’s participants might take the following form:

Goal: To identify and prioritize key user pain points in their current mobile app interface and develop actionable solutions to improve user satisfaction and engagement.

Agenda: Introduction and Warm-up (15 minutes).

Welcome participants and introduce the workshop goal.

Quick icebreaker activity to encourage creativity and collaboration.

User persona review: (30 minutes)

Briefly review existing user personas.

Discuss any recent user feedback or data that might impact our understanding.

Pain point identification: (45 minutes):

Brainstorming session to list all potential user pain points.

Group similar issues and categorize them.

Priority matrix exercise: (30 minutes)

Plot identified pain points on an impact vs. effort matrix.

Discuss and agree on top priorities to address.

Solution ideation: (60 minutes)

Break into small groups.

Each group focuses on one or two high-priority pain points.

They do rapid sketching and ideation of potential solutions.

Solution presentation and discussion: (45 minutes)

Each group presents their ideas.

Whole team discusses and provides feedback.

Action plan development: (30 minutes)

Outline next steps for the most promising solutions.

Assign responsibilities and set tentative timelines.

Wrap-up and reflection: (15 minutes)

Summarize key outcomes and decisions.

Collect feedback on the workshop process.

Total duration: 4 hours and 30 minutes. This agenda gives a clear structure for the workshop—with a focus where participants work to identify problems, prioritize them and then collaboratively develop solutions. It also permits time for discussion, decision-making and planning next steps—so actionable outcomes can arise.

Look at our piece, Workshops to Establish Empathy and Understanding from User Research Results for more.

Read our piece, How to Create a Perspective Grid for additional helpful insights.

A typical workshop might last between two and four hours—enough time to cover key topics in depth without overwhelming participants. Shorter workshops mightn’t provide sufficient time for meaningful discussion and practical exercises. Longer ones, meanwhile, can lead to fatigue and diminished levels of engagement.

Include regular breaks and interactive activities. Tailor the length of your workshop to the complexity of the material and the experience level of the participants.

Look at our piece, Workshops to Establish Empathy and Understanding from User Research Results for more.

Read our piece, How to Create a Perspective Grid for additional helpful insights.

An effective workshop includes clear objectives, engaging content and active participation. To start, define the goals to give participants a clear understanding of what they’ll learn. Use interactive methods like group activities, discussions and hands-on exercises to keep the content engaging.

Encourage participants to share their thoughts and experiences—it’ll enrich the learning process. Provide practical examples to illustrate key points, too. Plus, make sure there’s a well-structured agenda—and have it so there’s a good balance of presentation time and activities. What’s more, allow time for questions and reflection. Finally, collect feedback to improve future workshops.

Look at our piece, Workshops to Establish Empathy and Understanding from User Research Results for more.

Read our piece, How to Create a Perspective Grid for additional helpful insights.

Identify the target audience based on the workshop's objectives. Look for individuals who need the skills or knowledge you plan to teach. Consider the participants' current skill levels to make sure they can follow the material without feeling lost or bored.

Look for a mix of backgrounds and experiences to foster diverse perspectives and richer discussions. Review applications or conduct brief interviews to assess interest and fit. Aim to create a group size that permits meaningful interaction and personalized attention. That’s typically somewhere between 10 and 20 participants. This approach will make for a productive and engaging workshop experience for everyone who’s involved.

Look at our piece, Workshops to Establish Empathy and Understanding from User Research Results for more.

Read our piece, How to Create a Perspective Grid for additional helpful insights.

Essential tools and materials for a workshop include a projector, a whiteboard and markers for presentations and visual aids. Provide handouts and notebooks and pens or digital materials with key information and exercises.

Consider using sticky notes and flip charts for group activities and brainstorming sessions. A timer helps manage time effectively, and refreshments keep participants energized and focused.

If there’s a remote element to the workshop, webcams and appropriate software are also vital.

Watch our video on affinity diagrams to understand more about this helpful tool:

Use reliable video conferencing tools. Make sure there’s a stable internet connection and test all technology before the session. Share the agenda and materials in advance, so participants know what to expect. Keep sessions interactive with polls, Q&A and breakout rooms to keep everyone engaged with what’s going on.

Encourage participants to turn on their cameras and use headsets for better audio quality. Set ground rules for communication—like muting when not speaking. Include regular breaks to avoid screen fatigue. Follow up with participants after the workshop to provide additional resources and collect their feedback.

Look at our piece, Workshops to Establish Empathy and Understanding from User Research Results for more.

Read our piece, How to Create a Perspective Grid for additional helpful insights.

Effective icebreakers for workshops include simple introductions, where participants share their names and one interesting fact about themselves. Use "Two Truths and a Lie," where each person states three things, and others guess which one is false.

For virtual workshops, use tools like Poll Everywhere for quick, fun surveys. These icebreakers build rapport and create a comfortable environment—so participants get to be more willing to engage and collaborate.

Look at our piece, Workshops to Establish Empathy and Understanding from User Research Results for more.

Read our piece, How to Create a Perspective Grid for additional helpful insights.

Try to use group discussions and brainstorming sessions to encourage participation. Implement hands-on exercises related to the workshop content—they’ll let participants apply what they learn. Use role-playing scenarios to practice real-world situations. Also, try using interactive tools like live polls, quizzes and digital whiteboards.

Break participants into smaller groups for focused activities and collaborative tasks. Schedule regular Q&A sessions to address questions and encourage dialogue.

Look at our piece, Workshops to Establish Empathy and Understanding from User Research Results for more.

Read our piece, How to Create a Perspective Grid for additional helpful insights.

1. IDEO's Design Thinking workshops emphasize empathy, ideation, and prototyping to solve real-world problems.

2. Google's Design Sprint workshops focus on rapid prototyping and user testing within a five-day process, helping teams quickly validate ideas.

3. Stanford d.school's Bootcamp Bootleg workshop teaches creative problem-solving techniques and fosters collaboration through hands-on activities.

Moquillaza, A., Falconi, F., Aguirre, J., Lecaros, A., Tapia, A., & Paz, F. A. (2022). Using remote workshops to promote collaborative work in the context of a UX process improvement. In A. Marcus, E. Rosenzweig, & M. M. Soares (Eds.), Lecture Notes in Computer Science: Vol. 14032. Design, User Experience, and Usability: 12th International Conference, DUXU 2023, Held as Part of the 25th HCI International Conference, HCII 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark, July 23–28, 2023, Proceedings, Part III (pp. 254-266). Springer.

This publication is influential in the field of UX process improvement, particularly in the context of remote collaboration. The authors conducted a virtual workshop with stakeholders to collect feedback on the current process and propose improvements for the future process. The study identified 19 improvements for tree testing processes and 18 for heuristic evaluation processes—highlighting how effective remote workshops are in facilitating collaboration and knowledge sharing despite physical distance. The paper addresses the growing need for remote collaborative methods in UX design—especially in light of the increased reliance on virtual tools and environments. It provides a practical case study—one that shows how remote workshops can effectively collect valuable insights and drive process improvements. The findings emphasize how important stakeholder involvement is and the potential of remote workshops to achieve high-impact results.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Workshops in UX/UI Design by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Workshops with our course Build a Standout UX/UI Portfolio: Land Your Dream Job .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your expert for this course:

Morgane Peng: Designer, speaker, mentor, and writer who serves as Director and Head of Design at Societe Generale CIB.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!