Human Error

- 380 shares

- 1 year ago

Human errors are any actions users take that result in unintended outcomes or a failure to achieve a desired goal. Human error can occur due to slips, mistakes, or lapses. If designers consider human factors in interaction design, they can create more user-friendly and error-tolerant interfaces.

One of the primary goals of user experience (UX) designers’ work is to create products that are intuitive and error-free. However, despite designers’ best intentions, human errors can still happen when users interact with interfaces. These errors are often due to bad design choices that do not account for the limitations and behaviors of real users. And they can wreck the overall user experience, if not produce an even worse effect.

To err is human. Fortunately, you, as a designer, can minimize the chances that users will become frustrated with your product. Start by remembering that it’s easy to make the error of assuming your users won’t make mistakes. Human error, in a UX design context, refers to actions or decisions made by users that result in unintended or undesired outcomes. These errors can occur at various stages of the user's interaction with a product. That includes their initial understanding of the interface to the execution of their tasks. Errors can lead to frustration, loss of productivity, and even potential harm. So, it’s important to understand the types of errors and determine how to stay ahead of where your users might go wrong, and design to keep them on the right track.

As a designer, you have to factor in the potential for human error. You can’t take the “user” out of the user experience.

© Emanuel Serbanoiu, Fair Use

According to Don Norman, renowned expert in UX design, human errors come in two categories:

Slips – Slips occur when you don’t mean to do something. It could be because you’re just going too fast with the swipes or selecting items to delete, for example. Like slips in the physical world, users are likely to stumble in the digital world. These are the kinds of errors that can happen to us all. However, you can aim ahead to help users minimize these as far as possible.

Mistakes – Mistakes are intentional errors. However, they don’t occur because users want to sabotage their tasks or goals. Mistakes happen when a user has developed an incorrect mental model of the interface and forms a goal that doesn't suit the situation well. These errors are, therefore, intended actions, but they’re actions that aren’t appropriate for the problem at hand. They come from a misunderstanding of the system's state. Or it could be that the user has a poor interpretation of the interface. A classic example is a Norman door—for instance, a door with a pullable-looking handle, but users can only push the door to open it. As a designer, you can help users prevent mistakes by giving them an accurate idea of what to do through an intuitive interface, for example.

In addition to these, a third category of human error is:

Lapses – Lapses tend to happen when a user's attention is not focused on the task at hand. These errors are usually caused by distractions, fatigue, or being on “autopilot” mode. They are much like slips, but involve failing to stick to an original plan you had intended to follow. This could be forgetting to do something you had meant to do, or taking an action you hadn’t initially planned to execute.

Lapses are often more difficult to anticipate and prevent than slips and mistakes. That’s because users may not always be aware of their lack of focus. An example of a lapse is forgetting to log into a website to update your account information. So, you might help minimize this problem by giving users a reminder to do some needed or recommended action, for instance.

User errors can arise very easily, and aren’t always about a fundamental failure to understand a concept.

© George Becker, CC BY-SA 4.0

As a designer, it is important to remember the potential for slips, lapses and mistakes in user behavior from the beginning of your design process. Also, it’s vital to try to minimize these through the design choices you make along the way, while still allowing your users some flexibility on your interface.

Here are some common examples of how bad designs can influence human errors:

Directional cues play a crucial role in guiding users. They guide users through an interface and help them understand how to interact with different elements. When a design lacks clear directional cues, users may struggle to navigate the interface and end up making errors. For example, a website may fail to provide clear visual indicators for clickable elements. So, users may click on the wrong areas or miss important actions, leading to errors.

Amazon’s site has a handy “safeguard” to keep users on the right track – search suggestions that are also clickable are great aids for users.

© Amazon, Fair Use

Error messages are essential for informing users about issues or mistakes they've made while using a product. However, when error messages are confusing or ambiguous, users may not understand the problem or how to correct it. This can lead to frustration and further errors. It’s important to provide clear and informative error messages that guide users towards resolving the issue.

Dropbox tells users precisely where they’ve gone wrong in clear and unambiguous terms.

© Dropbox, Fair Use

Complex or overwhelming interfaces can “throw” users and greatly increase the likelihood they’ll make errors. Sometimes, users encounter too many elements, options, or features on the screen. Then, they may struggle to find what they need or execute the correct actions. Indeed, human errors can arise from the design of a complex or overwhelming interface, and all too easily. With risks to human life and property running sky-high in more severe cases, it’s an important point to remember also for hand-held devices. Despite the differences in potential—that is, loss of life and limb and destruction of property versus a user’s failing to use an app correctly—designers should consider one thing in particular: for users, nothing is “trivial” when they are serious about a product or service.

Here, Don Norman recounts his work with complex systems, their users, as well as a notable and costly disaster, before he explains the principles of human-centered design from his experience with people and systems.

Airplane Cockpit by Riik@mctr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/riikkeary/24184808394/

Cognitive Science building at UC San Diego. by AndyrooP (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cognitive_Science.jpg

Pseudo-commands to illustrate how line-by-line text editing works. by Charlie42 (CC BY-SA 3.0)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ed_(text_editor)#/media/File:Ed_lines.jpgHowever, when you simplify the interface and prioritize essential elements, you can help users focus on their tasks and reduce the occurrence of errors.

Google’s homepage is a definitive example of a simple and highly effective user interface. Thanks to a thoughtful layout, featuring generous use of white space, the chances that a user becomes overwhelmed are practically nonexistent.

© Google, Fair Use

Feedback is crucial in helping users understand the outcome of their actions and confirming that they have completed tasks successfully. A design may lack proper feedback mechanisms or fail to provide confirmation for critical actions. Therefore, users may be uncertain about the results of their interactions, leading to errors. Incorporating visual cues, notifications, or confirmation dialogs can help reduce ambiguity and improve user confidence.

Windows offers feedback to users in no uncertain terms regarding what may happen next.

© Microsoft, Fair Use

Here are some practical approaches to minimize human errors and create user-friendly experiences:

Clear and simple designs can significantly reduce the frequency of human errors. This is why it’s important to know and leverage design principles. So, when you prioritize clarity in visual elements, content presentation, and navigation, you can ensure that users understand the interface. From there, they can easily execute tasks without confusion or mistakes. Use clear labels, intuitive icons, and logical grouping of elements to guide users effectively.

Notion presents fine clarity on its homepage in a clean, clearly labeled and attractively presented way.

© Notion, Fair Use

Visual cues and affordances help users understand how to interact with different elements in an interface. It’s important to utilize consistent and recognizable visual cues, such as buttons, icons, or hover effects. That way, you can provide clear indications of functionality and reduce the chances of user errors. Affordances, such as buttons that appear clickable or toggles that indicate on/off states, help users understand the available actions. And so, they prevent unintended errors.

Avast Cleanup offers clear affordances and cues to keep users informed and clued up at a glance about available actions.

© Avast, Fair Use

Keep users on the right track by keeping them away from the wrong ones. For example, a radio button only allows users one course of action at a time. Or frozen or grayed-out buttons or fields show them they need to focus on the proper or “live” ones. A classic real-world example is booking airline tickets or accommodation.

Airbnb’s website applies the convention of graying out dates to let you know you can’t select dates in the past or unavailable dates for a booking.

© Airbnb, Fair Use

Real-time feedback and validation play a crucial role in preventing errors. By providing immediate feedback when users perform actions or input data, you can help them catch and correct errors early. For example, displaying error messages next to problematic form fields or highlighting missing information can guide users toward resolving errors promptly.

X Corp.’s message alerts a user that their account is unfindable – perhaps due to a mistype in the login field.

© X Corp., Fair Use

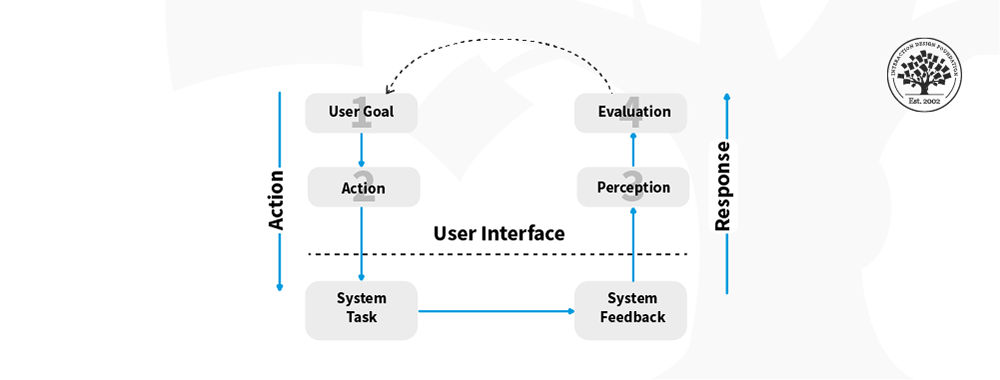

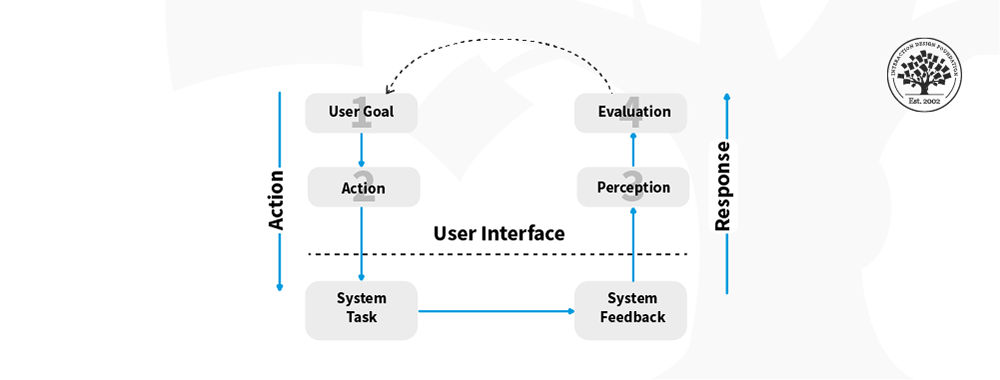

Always consider the user's context and mental models when creating interfaces. Do UX research and keep to user-centered design. By understanding the users' goals, expectations and prior knowledge, you can align the interface design with users' mental models. That will reduce the chances of errors caused by mismatches between user expectations and the interface behavior.

For example, if your app uses GPS to direct users to services, leverage their mental model of using a traditional paper map. Some mental models are easier to apply than others, but if you do your user research well, you can inform design decisions that will work well.

Airbnb draws on users’ mental model of booking a hotel room or vacation rental, keeping to a similar process of searching, comparing listings and booking.

© Airbnb, Fair Use

A clear and consistent visual hierarchy helps users understand the importance and relationships between different elements on the interface. By using visual cues such as size, color, and placement, you can guide users' attention to critical elements. That will reduce the risk of errors caused by overlooking important information.

Mailchimp uses color, size, white space, and contrast in its homepage, which features highly distinguishable elements. Users have clear guides to key actions.

© Mailchimp, Fair Use

Complex and convoluted interactions increase the likelihood of user errors. Strive to simplify and streamline interactions. That will reduce the cognitive load on users. And it will make it easier for them to accomplish their goals without confusion or frustration.

Uber’s ride-booking process is ultra-streamlined for users who land on the homepage (top screenshot in image above) to proceed to the next easy step (bottom).

© Uber, Fair Use

© Uber, Fair Use

Incorporate safety measures to prevent users from accidentally committing to irreversible actions. Implement confirmation dialogs and provide clear warnings before executing irreversible actions. These can help users avoid errors and the resulting consequences and pain points. For example, Windows asks users if they’re sure they want to permanently delete items before they commit to the action of, for example, emptying their PC’s trash can.

Conduct user testing sessions and gather feedback throughout the design process. It is crucial for identifying potential sources of human error. Usability testing can weed out users’ problems with the information architecture and many other aspects of user interface (UI) design. So, for testing user interfaces effectively, be sure to recruit participants in your UX design process and product development who can give you the user feedback you need. Variety is key for finding out much about what can go wrong. Whether it’s accessibility-related or something perhaps more intricate, when you involve users in the design process, you can gain valuable insights and iterate on your designs. You can then improve usability and minimize human errors.

Remember, human errors can often be attributed to bad design choices that misunderstand user flow. So, understand the various types of human errors and the impact of bad design on those errors. And implement effective design strategies that always stay one step ahead of your target audience at every point on their customer journey. Doing so, you can put the user on the right path every time, and help them minimize errors—or even avoid errors—when using your products.

Take a deep dive into Human Error with our course Design for Thought and Emotion.

Find further insights in this thought-provoking piece, Human Error or Design Error? | by Sneha Munot.

Find further fascinating insights in this academic work, Human Interface/Human Error by Charles P. Shelton.

For more tips and insights on slips, read this article by Page Laubheimer, Preventing User Errors: Avoiding Unconscious Slips (NNG).

For more tips and insights on mistakes, read this article by Page Laubheimer, Preventing User Errors: Avoiding Conscious Mistakes (NNG).

According to Don Norman, renowned expert in UX design, human errors come in two categories:

Slips – Slips occur when you don’t mean to do something. It could be because you’re just going too fast with the swipes or selection of items to delete, for example. Like slips in the physical world, users are likely to stumble in the digital world. These are the kinds of errors that can happen to us all. However, you can aim ahead to help users minimize these as far as possible.

Mistakes – Mistakes are intentional errors. However, they don’t occur because users want to sabotage their tasks or goals. Mistakes happen when a user has developed an incorrect mental model of the interface and forms a goal that doesn't suit the situation well. These errors are therefore intended actions, but they’re actions that aren’t appropriate for the problem at hand. They come from a misunderstanding of the system's state. Or it could be that the user has a poor interpretation of the interface. A classic example is a Norman door—for instance, a door with a pullable-looking handle but users can only push the door to open it. As a designer, you can help users prevent mistakes by giving them an accurate idea of what to do through an intuitive interface, for example.

In addition to these, a third category of human error is:

Lapses – Lapses tend to happen when a user's attention is not focused on the task at hand. These errors are usually caused by distractions or fatigue. They are much like slips, but involve failing to stick to an original plan you had intended to follow. This could be forgetting to do something you had meant to do, or taking an action you hadn’t initially planned to execute.

Lapses are often more difficult to anticipate and prevent than slips and mistakes. That’s because users may not always be aware of their lack of focus. An example of a lapse is forgetting to log into a website to update your account information. So, you might alleviate this problem by giving users a reminder to do something, for instance.

Here are some effective approaches to minimize human errors and create user-friendly experiences to help users feel more in control and your product team stay on point with the business goals:

1. Prioritize Clarity and Simplicity

Clear and simple designs can significantly reduce the frequency of human errors. This is why it’s important to know and leverage design principles. So, when you prioritize clarity in visual elements, content presentation, and navigation, you can ensure that users understand the interface. From there, they can easily execute tasks without confusion or mistakes. Use clear labels, intuitive icons, and logical grouping of elements to guide users effectively.

2. Provide Visual Cues and Affordances

Visual cues and affordances help users understand how to interact with different elements in an interface. It’s important to utilize consistent and recognizable visual cues, such as buttons, icons, or hover effects. That way, you can provide clear indications of functionality and reduce the chances of user errors. Affordances, such as buttons that appear clickable or toggles that indicate on/off states, help users understand the available actions. And so, they prevent unintended errors.

3. Disallow Inappropriate Actions

Keep users on the right track by keeping them away from the wrong ones. For example, a radio button only allows users one course of action at a time. Or frozen or grayed-out buttons or fields show them they need to focus on the “live” ones. A classic real-world example is booking airline tickets or accommodation.

4. Offer Real-Time Feedback and Validation

Real-time feedback and validation play a crucial role in preventing errors. By providing immediate feedback when users perform actions or input data, you can help them catch and correct errors early. For example, displaying error messages next to problematic form fields or highlighting missing information can guide users towards resolving errors promptly.

5. Consider User Context and Mental Models

Always consider the user's context and mental models when creating interfaces. Do UX research and keep to user-centered design. By understanding the users' goals, expectations and prior knowledge, you can align the interface design with users' mental models. That will reduce the chances of errors caused by mismatches between user expectations and the interface behavior.

For example, if your app uses GPS to direct users to services, leverage their mental model of using a traditional paper map. Some mental models are easier to apply than others, but if you do your user research well, you can inform design decisions that will work well.

6. Create a Clear and Consistent Visual Hierarchy

A clear and consistent visual hierarchy helps users understand the importance and relationships between different elements on the interface. By using visual cues such as size, color, and placement, you can guide users' attention to critical elements. That will reduce the risk of errors caused by overlooking important information.

7. Provide Simplified and Streamlined Interactions

Complex and convoluted interactions increase the likelihood of user errors. Strive to simplify and streamline interactions. That will reduce the cognitive load on users. And it will make it easier for them to accomplish their goals without confusion or frustration.

8. Help Prevent Irreversible Actions

Incorporate safety measures to prevent users from accidentally committing to irreversible actions. Implement confirmation dialogs and provide clear warnings before executing irreversible actions. These can help users avoid errors and the resulting consequences and pain points. For example, Windows asks users if they’re sure they want to permanently delete items before they commit to the action of, for example, emptying their PC’s trash can.

9. Conduct User Testing and Do Iterative Design

Conduct user testing sessions and gather feedback throughout the design process. It is crucial for identifying potential sources of human error. Usability testing can weed out users’ problems with the information architecture and many other aspects of user interface (UI) design. So, for testing user interfaces effectively, be sure to recruit participants in your UX design process and product development who can give you the user feedback you need. Variety is key for finding out much about what can go wrong. Whether it’s accessibility-related or something more intricate, when you involve users in the design process, you can gain valuable insights and iterate on your designs. You can then improve usability and minimize human errors.

Here are some common examples of how bad designs can influence human errors, including brands that show how to design to best avoid these in terms of design elements and more:

1. Lack of Clear Directional Cues

Directional cues play a crucial role in guiding users. They guide users through an interface and help them understand how to interact with different elements. When a design lacks clear directional cues, users may struggle to navigate the interface and end up making errors. For example, a website may fail to provide clear visual indicators for clickable elements. So, users may click on the wrong areas or miss important actions, leading to errors.

2. Confusing or Ambiguous Error Messages

Error messages are essential for informing users about issues or mistakes they've made while using a product. However, when error messages are confusing or ambiguous, users may not understand the problem or how to correct it. This can lead to frustration and further errors. It’s important to provide clear and informative error messages that guide users towards resolving the issue.

3. Complex or Overwhelming Interfaces

Complex or overwhelming interfaces can “throw” users and greatly increase the likelihood they’ll make errors. Sometimes users encounter too many elements, options, or features on the screen. Then they may struggle to find what they need or execute the correct actions. When you simplify the interface and prioritize essential elements, you can help users focus on their tasks and reduce the occurrence of errors.

4. Lack of Feedback and Confirmation

Feedback is crucial in helping users understand the outcome of their actions and confirming that they have completed tasks successfully. A design may lack proper feedback mechanisms or fail to provide confirmation for critical actions. Therefore, users may be uncertain about the results of their interactions, leading to errors. Incorporating visual cues, notifications, or confirmation dialogs can help reduce ambiguity and improve user confidence.

The ideal is to design interfaces that are difficult to use incorrectly. But human error cannot be completely eliminated, so you as a designer must also anticipate errors and build in recovery mechanisms to minimize adverse consequences. The aim is to prevent errors whenever possible and support recovery when errors occur.

UI features like date pickers that contain greyed-out dates, greyed-out buttons that are inoperable because they are inappropriate for the course of action the user needs to take, and radio buttons that keep users to one course of action are examples of features you can use to minimize human error.

Here are some highly cited research papers about human error, which designers and developers can learn much from:

1. Reason, J. (1990). Human error. Cambridge university press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/human-error/49E5409F03017774D32463BBED7BA233

This seminal book by James Reason synthesizes research on human error and organizes it within a conceptual framework that has become highly influential in human factors and UX design. It distinguishes between slips, lapses, mistakes and violations and discusses error prevention strategies.

2. Norman, D. A. (1988). The psychology of everyday things. Basic books. https://www.jnd.org/the-psychology-of-everyday-things.html

This classic book by Donald Norman introduces the concept of user-centered design and the role of psychology in designing for errors. It provides principles for design to minimize errors and illustrates concepts such as affordances, constraints, mapping and feedback.

3. Nielsen, J. (1994). Usability inspection methods. In Conference companion on Human factors in computing systems (pp. 413-414). https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/259963.260531

This highly cited paper proposes heuristic evaluation as an efficient usability inspection method for identifying usability problems and issues that can lead to human error. Nielsen provides a set of ten general heuristics as criteria for inspection.

4. Lewis, C., & Norman, D. A. (1986). Designing for error. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 211-217). https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/22627.22367

This classic paper proposes design principles and strategies based on an understanding of human cognition and limitations. It covers forcing functions, natural mappings, affordances and feedback to design interfaces that are error-tolerant.

5. Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive science, 12(2), 257-285. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4

This highly cited paper introduces cognitive load theory and its implications for instructional design and usability. It suggests minimizing working memory load to reduce errors, especially for novice users.

6. Krug, S. (2014). Don't make me think, revisited: A common sense approach to web usability. New Riders. https://www.stevekrug.com/books/dont-make-me-think-revisited/

This classic book provides principles and tips for web usability with a focus on minimizing confusion and cognitive load that can lead to errors. It advocates user testing to identify problematic areas.

7. Zhang, J., & Norman, D. A. (1994). Representations in distributed cognitive tasks. Cognitive science, 18(1), 87-122. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1207/s15516709cog1801_3

This paper analyzes distributed cognition and implications for user interface design. It proposes external representations be designed to minimize translation, interpretation and search to reduce errors.

8. Dix, A., Finlay, J., Abowd, G. D., & Beale, R. (2004). Human-computer interaction (3rd ed.). Pearson Education. https://www.pearson.com/us/higher-education/program/Dix-Human-Computer-Interaction-3rd-Edition/PGM80723.html

This textbook provides a comprehensive introduction to HCI including chapters on human error and error prevention strategies like undo, warnings, confirmation etc.

9. Kirwan, B., & Ainsworth, L. K. (1992). A guide to task analysis: the task analysis working group. CRC press. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.1201/9781351068422/guide-task-analysis-barry-kirwan-linda-k-ainsworth

This book presents techniques for cognitive task analysis to uncover areas prone to human error during task performance. It provides methods to understand user knowledge, thought processes and goals.

Here are some recommended books that cover Human Error in UX design well:

● The User Experience Team of One: A Research and Design Survival Guide by Leah Buley: This book helps UX designers and researchers better understand the importance of human psychology in design and enables them to deepen their understanding of what makes designs outstanding.

● Mental Models: Aligning Design Strategy with Human Behavior by Indi Young: This book explores how to align design strategy with human behavior, providing insights into how people think and make decisions.

● Usable Usability: Simple Steps for Making Stuff Better by Eric Reiss: This book offers practical steps for improving the usability of designs, focusing on the needs and behaviors of users.

● 100 Things Every Designer Needs to Know About People by Susan Weinschenk: This resource provides valuable insights into human behavior and cognition for UI/UX designers, helping them create more effective designs.

● The Design of Everyday Things by Don Norman: While not specifically focused on human error, this book covers the fundamentals of design, including why some things feel uncomfortable and others feel delightful to use, which can help designers understand and mitigate potential errors in their designs.

● Don't Make Me Think (Revisited) by Steve Krug: This practical guide to UX design offers insights into how to create intuitive and user-friendly interfaces, reducing the likelihood of user errors.

● Rocket Surgery Made Easy by Steve Krug: This book provides a step-by-step guide to conducting usability testing, helping designers identify and address potential user errors in their designs.

● Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman: Although not strictly a design book, this work explores human decision-making processes, which can be valuable for understanding and addressing potential errors in UX design.

● Designing with the Mind in Mind by Jeff Johnson: This book distills human behavior and cognition for UI/UX designers, covering topics such as learning behavior, decision making, and how we remember actions, which can help designers create more effective and error-free designs.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Human Error by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Human Error with our course Design for Thought and Emotion .

Throughout the course, the well-respected author and professor of Human-Computer Interaction, Alan Dix, will give valuable insights into the basics of thought and emotion. He will also touch on how these factors influence us as designers of interactive systems.

Portfolio Project

In the “Build Your Portfolio: Thought and Emotion Project”, you’ll find a series of practical exercises that will give you first-hand experience in applying what we’ll cover. If you want to complete these optional exercises, you’ll create a series of case studies for your portfolio which you can show your future employer or freelance customers.

Gain an Industry-Recognized UX Course Certificate

Use your industry-recognized Course Certificate on your resume, CV, LinkedIn profile or your website.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!