Improving Your Content Design Strategy using UX Ideas

- 537 shares

- 2 years ago

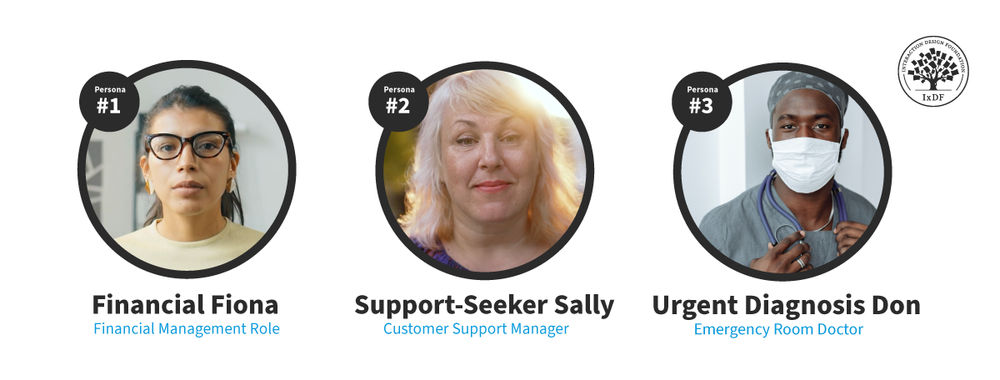

Personas are fictional, research-backed representations of the people designers aim to delight with their products, services, and experiences. They are based on real user needs, behaviors, and motivations. In user experience (UX) design, personas promote empathy, align teams, and give focus to design and development processes.

“Personas represent the needs and behaviors of a subset of users your product aims to delight.”

— William Hudson

In this video, William Hudson, User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd, gives an overview of personas.

Personas are representations of our *users*. They promote empathy by allowing us to focus on individuals rather than groups. It's this whole issue of empathy. We keep talking about "users". And even just talking about the *roles* like "customers" or "clerk" or "salesperson" doesn't make these roles seem real. It doesn't. We're not talking about real people. Real people have limited abilities.

Real people don't necessarily get computers in the same way that the development team does. Real people have needs that have been brought up by their circumstances or by their own personal beliefs. So, we need to know a bit *about* them. And personas are a great way of representing those understandings in the design of a real system. So, there is strong psychological evidence for *personal bias*. Our brains are wired to *empathize with individuals rather than groups*. The general feeling is that when we dehumanize people by referring to them

with these abstract collective nouns – because collective nouns *are* abstract by definition, so we're talking about "users" or we're talking about "customers" – we're taking the "people" away. We need to put the "people" back. Back in 1983, David Sears ran a study with two sets of participants. He gave the participants the same characteristics. And in one set of participants he said that these characteristics were of

*an individual*. And I believe he described the individual. And in the other set participants he said that these characteristics were of *a group of people*. And the participants who were told that they were seeing the characteristics of an individual *always rated the individual more highly* than the participants who rated the characteristics in connection with a group. So, that he called the *person-positivity bias*. And it basically is confirmation that our brains

– us as individuals – *prefer thinking about other individuals*. We're certainly more inclined to think more positively about other individuals than we are about collective nouns like "tourists" or "customers" or "users". The *scope-severity paradox* is a much more recent piece of work – 2010 – and is quite surprising. Two researchers, Nordgren and McDonnell, established that reactions to a fraud were more severe when it was presented with three victims rather than 30. So, it's the same kind of deal: two sets of participants,

both given exactly the same details of a crime, except that in one group they were told it affected three people and the other group were told it affected 30 people. And it was the people who were told that there were only three victims that thought that the crime was more severe. And they, on average, added a year on the prison sentence that the perpetrators of this crime should receive. So, again, that is just confirming this tendency for us to feel more strongly about individuals than we do about groups.

Personas are fabrications *based on research*. We mustn't let go or lose sight of that little parenthetical expression there, because we go out and we find out who these people are – the ones that we're interested in – find out what behaviors they have which drive them to need our solution, what motivations, what their circumstances are, what their contexts of use are,

just so we understand who we're building the solution for and other aspects that we describe in the context of use. These personas are representations of our users, who represent the goals, behaviors and motivations of those real users. They *promote empathy* by allowing us to *focus on individuals rather than groups*. So, instead of talking about "User Community One" or whatever catchy name we'd like to come up with for our user communities, we start talking about "Bob"

or "Jane" or "Elizabeth" – whoever – whatever everybody in the team is happy with. And there have been all kinds of documents and papers and studies written about personas. And you'll find that personas range from quite a limited description of a person. And, in fact, it can be just as little as changing the name "users" to a person's name. So, if you always refer to your customers as "Andrew", then you would actually

be doing yourselves a favor in terms of making that customer seem much more real. But at the other extreme it's not uncommon to hear about user research and persona development taking *weeks* – possibly even months: 2–3 months, which is, in my view and and quite a few others', certainly for an Agile environment well beyond the realms of possibility. So, we're going to be talking about something called a *minimal persona*. So, minimal persona – a name, age and other specific demographic details that a real person

would have. A photo – ideally realistic – showing the person in that setting or doing that thing. And then, basic information about why you're interested in them or why they're interested in us – our solution or product. So, their *primary goals*: *why* those are their primary goals and *what* they're hoping to achieve through our solution or product. And their *behaviors* – what are they doing before and after interaction with our solutions

fit with their daily routine, for example. And some of this comes from the fact that I have for years been astounded by how little the people developing software solutions know about their users. I've been involved in a couple of projects where there was no contact whatever. The development team had never met or seen a user, didn't know what the user was doing immediately prior to entering or receiving data from their system, didn't know what happened to the output data, knew almost nothing.

So, it wasn't surprising that the system when it was first launched was almost impossible to use, because it didn't actually fit. It was like having a random piece of a jigsaw puzzle and a very well-defined hole that it just did not slip into. So, these are the reasons we're trying to actually make sure that we understand at least something about our user communities. And that's what personas are trying to help us with. *Extended personas* – you might add lifestyle interests,

hobbies, as they apply to their motivations. I wouldn't add them just to make the person seem more complete. That isn't absolutely essential. But if some of those issues – lifestyles, interests or hobbies have an impact on your solution, then you should know about them. So, *keep to the details that are relevant* to the problem. Remember that we want to *motivate our team to help* our personas, *not* to drive them crazy with distracting detail, which is one of the complaints you will hear about personas.

Certainly when I've attended conference research papers on the use of personas in teams, often they were not well-received, because there just seemed to be so much of it – the persona specification. *Credibility*: ensure that the personas are *believable* and liked *as much as possible*. Certainly do *not* give personas unpleasant or dubious habits like being a heavy drinker or a heavy smoker or likes to bet on the horses – unless, of course, you're building a gambling app or something! *Change the name, photo and other details* until the whole team is comfortable with them.

It needs to be a collaborative effort between the user experience people and the people who are going to be using them. That would be the development team. So, the names and the photos are almost entirely arbitrary. If you've done research with a handful of participants, then you'd have a handful of photos. If not, then try to find photos from a stock photo site. But try to avoid overtly attractive people because it can be distracting. In user experience, we create often what are referred to as "design research personas",

or "design personas" for short. So, that's what these things are technically called. We go out and we research these user communities. We decide what behaviors and needs are relevant to us: Who are we building the solution for? And those personas are based on this design research. So, that's why we want to call them "design research personas" or "design personas". But there are lots of other things that also get tagged with personas.

And the most common of those I've come across, particularly in large companies, are *market research personas*. And they're not the same thing is the main problem that we have. So, beware that *other kinds of personas exist*, often based on demographics or market segmentation. These can be used for *validating design personas, but should never replace them*. There is little point in trying to reuse personas for different projects, as well, unless the same goals, motivations and behaviors are relevant.

And I've come across this whole approach in one particular vertical market in the U.K. And that is mobile phone service providers – that they have all got marketing personas based on age ranges. And they then attach labels to these age ranges to suggest how these people behave and what they need from our services, which, just to be honest, cannot really be true! You need to actually *forget about the demographics*. There will be some age-related behaviors, no doubt. But they shouldn't be

the motivating factors in the design of an interactive system, which is, after all, what we're trying to achieve. The main thing is that predominantly you have *one* or *two* primary personas. If you've got a project – and I've had people kind of come up to me almost in a boasting tone, saying: "Our project has got 20–30 personas!" And I'd say, "Oh, really? How is that?" They'd say, "Well, it's a hospital system." And the thing is, it's a *very* big system. And what you need to make it agile and to make these things work effectively

is to split the system into parts. So, you may well have some small number of primary personas that apply throughout. But in many cases you're going to have primary personas that are specific to that kind of system or that part of a system. So, let me give you some very simple examples. The one that I like to use is a hotel self-check-in. When I started writing about hotel self-check-ins, there were none in existence. And now I do come across them, funnily enough, in hotels that have got receptionists but all they do then is to

refer you to the self-check-in in front of the reception! I was motivated for this example by checking in at a conference hotel on one occasion. I actually got in pretty easily. I think it was a 20- or 30-minute process. But the next day I was walking through the reception and the queue – the line – of people waiting to check into this hotel went around the block. It was just utterly amazing. There must have been 200 or 300 people waiting to get in.

So, it occurred to me: "Well, why don't we just have some self-check-ins like we do at airports?" And, of course, self-check-in at airports is entirely bog-standard these days – it's what everyone does. So, for example, the primary persona of a hotel self-check-in service must be the customer checking in. It makes no sense for it to be otherwise. A *secondary persona* would be someone who is acting in a *supporting role* inside that system. So, a secondary persona might be a hotel manager or a receptionist or somebody who's

responsible for the upkeep of the hotel, for example. So, these are all *secondary roles*. They're not the people for whom we are building the system. They are people who are *involved in* the system and often in a backroom kind of interaction. These are people that primary personas rarely see or even know about. So, it's a difference between the primary roles in a stage production and just extras or people with non-speaking parts. That is kind of the difference between primary and secondary personas.

A lot of systems may have *only one* persona. This is the person that we're building this particular product for. And you can have all kinds of philosophical arguments about whether you're building a Swiss Army knife solution or whether you're building a carving knife solution. One is very good at one thing. Carving knives are very good at carving. Swiss Army knives are very good, but in a fairly different kind of way, at *all kinds* of things.

But they're not all that easy to use. So, it's up to you. The whole point of personas is to try to *give focus*. So, these are our customers. Other people, who do not fall into the definition or the descriptions of our personas, it's fine if they find our system easy to use. But unless we can actually identify some clear purpose in adapting the system to be more inclusive, then we would deliberately not pay much attention to their particular requirements. Now, things like *accessibility* and the *age ranges* of users – they fall outside the whole persona mechanism.

You must *always make sure that your systems are usable by those with disabilities* whether that's acknowledged specifically in your persona or not. I do have at least one colleague who, if they're dealing with a team who has little experience of accessibility – that is, systems that will be used by disabled people – he deliberately includes a disabled persona. But that really ought not to be necessary. But if that works for you, then that's absolutely fine, too.

Certainly I can see it being important when working with teams that don't have much experience. So, you must make sure that your solutions work for a *broad range of people* in terms of *accessibility* and *age issues*. But otherwise, we want to be very focused on the *specific behaviors* and *needs* of our primary personas. So, we stick to small numbers to maximize empathy. And we consider splitting larger projects, as I was discussing for the hospital example. For example, a hotel check-in system could be split into front desk and housekeeping projects

with separate personas. So, those could be two smaller Agile projects. And there is no magic number. But, like I have been saying, 1 or 2 primary personas is perhaps the most common, with maybe a few secondary personas thrown in, as well. Personas get used in all sorts of places. Obviously, their main focus is in *design*. So, "Who are we building this product for? How should the interactions take place? How much experience can we rely on them having of this kind of solution?" and so forth.

We will have to *recruit* these people. We want to do *research* with them, perhaps continuing research over several life cycles of the system. We want to recruit people for usability testing and user evaluation / usability evaluation in general, not just running them through early beta releases of the software. We might want to be testing with paper prototypes. We might be wanting to show them just wireframes and talking to them about the layout

and their understanding of the different components of the page and those sorts of issues. Sales and marketing will want to know *who* they should be targeting in terms of what the system does and for whom. And remember that you will need to describe the *demographics* and the *filtering questions* for your personas to a recruiter. So, when you're recruiting "Arthurs", what is it about Arthur that makes him your persona? It needs to be something that he wants or needs or you're *hoping* that he wants or needs. He needs a solution to a problem. So, what is that problem?

So, you need to actually talk to your recruiters about filtering questions. You know, what are you going to ask *potential Arthurs* that's going to help you to decide whether this person is really an Arthur? Now, this is quite an interesting area. And it may depend a lot on how enthusiastic your team is about personas. If you've done your job right, if you've *sold* personas, or if your team is already quite familiar and quite enthusiastic about personas,

then you might do some really fun things like getting mugs and coasters printed with maybe the face of the persona on one side and some of their relevant details with respect to your system on the other side. Ditto with mugs, maybe even T-shirts. And one thing that I was quite amused by – and I could actually see this working for some teams – is life-size cardboard cutouts. That's another possibility. So, you could actually have a room with your personas kind of standing around in unused corners.

I do know of organizations – I have heard of organizations – that would actually give the persona a desk, particularly if they were building a system for somebody in-house. And they might actually put all the stuff to do with that persona on the desk, just to make that person seem more real – you know. "Arthur would always be on holiday, but there's his desk" kind of thing. And I should mention – I'll just point out this very last thing – because it's quite important: at the very least, personas should appear in *easy-to-read* form on the project workspace

– whatever – sometimes, you'll hear this phrase – I used to hear it; I don't know that I've heard it very often – called "information radiators". Well, they're what you and I might refer to as "walls" or "partitions". They're the vertical spaces in your workspace. And you would pin important things to that, like all of the backlog for the next cycle and the design maps. So, these are things which everybody who's working on the project would actually be able to refer to quite readily. You might even hand these out in laminated plastic form,

just so everybody has easy access to them, for example.

Images

Copyright holder: Benoît Prieur. Appearance time: 10:32 - 10:36 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 4.0. Modified: No. Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Avenue_Berthelot-_machine_pour_entrer_dans_l%27h%C3%B4tel.jpg

“Personas are the single most powerful design tool that we use. They are the foundation for all subsequent goal-directed design. Personas allow us to see the scope and nature of the design problem… [They] are the bright light under which we do surgery.”

— Alan Cooper, Software designer, programmer and the “Father of Visual Basic”

Personas are not just demographic profiles or generic “user types”—they embody the goals, behaviors, motivations, and contexts of real users. Design teams create personas from user research, not assumptions. Research-backed personas enable designers and stakeholders to make confident decisions about a solution’s features based on users’ real needs. When personas are based on assumptions, they are unreliable and can result in products that do not meet user needs or expectations.

A persona is typically represented on one or two pages with key information. If a persona is too long or detailed, it is often difficult to design for and goes unused.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Crucially, personas replace roles (like “admin” or “guest”) or customer segments as the focus of design. However, just like real people, personas can take on multiple roles. For example, the Mary-Jane persona above might be both a buyer and a seller on an online marketplace.

In UX and product design, personas are referred to as user personas, UX personas, design personas, or, simply, personas. Without them, teams often design for a vague idea of “users” that are more a collection of assumptions than insights. This leads to products overloaded with features nobody asked for, mismatched workflows, and frustrated users. Personas bring focus, alignment, and empathy.

In this video, William Hudson explains the importance of personas and user research to the design and development process.

Why personas? Why do we introduce these fairly unusual features into our design process? And the answer is, we don't naturally do user-centered design. If you are in user experience design or user-centered design, that may sound a little unusual to you, but still, the vast majority of systems do not really focus on users in the way that we need them to. Personas are a way to get that focus, and they really are very much about focus.

And some of the anomalies in the descriptions of personas over really the past 20 or more years, since they were introduced, have kind of muddied that water. They've led us away from, the true point. We're going to be talking about the problems that we have with, low awareness of users. I teach software engineering courses, and they are just now starting to have a little content about

usability, but still, nothing about user research and how you decide how to design a system in terms of making it suitable for its intended audience. So, there really isn't any understanding of who the users are, what they need, and how they work. We still do see a lot of references to roles. Roles in organizations are fantastically problematic because often the people who are in

those roles don't even understand them fully, yet we're using them in software development to try to describe the needs of a user. I'm afraid it's a little bit nonsensical. And in a lot of cases, we have a very strong technology focus. This can be within a team or within an entire organization. If you're working within an engineering organization, for example, the idea that the engineers should be going out and talking to others to decide what they should

build is moderately unusual in many instances. So, that is a pretty big issue in terms of, the absence of users and the avoidance, almost by definition, of user-centered design. If you don't know anything about the users, you cannot do user-centered design.

Here’s why design teams use personas:

They Create Focus: Personas act as a design compass. When faced with a decision, designers can ask, for example, “Would this help Mary-Jane accomplish her goal?” This clarity avoids “feature creep,” which occurs when a product becomes overloaded with features that reduce usability and waste resources.

They Humanize Users: “User” is an abstract term. Personas replace “users” with someone specific. This approach promotes cognitive empathy—the ability to recognize that other people may think and behave differently than you do. In this video, William Hudson explains cognitive empathy and why we should design for individuals, not groups.

There's quite a lot of psychological evidence that empathy is geared towards individuals. And I want to talk about two long-standing research studies. One from 1983 by David Sears, called "The Person Positivity Bias", where he presented two sets of participants with exactly the same attributes. One set of participants was told that these attributes applied to a person,

an individual, and the other group of participants was told that these attributes applied to multiple people. And the participants who thought they were having the descriptions of individuals thought more highly of those individuals than the other participants did of the groups. So, that is pretty strong evidence for the person positivity bias, as he called it. The second study is by Nordgren and McDonnell, and they established that the reactions to a fraud were more severe

when it was presented with only three victims rather than 30. The two sets of participants were given exactly the same details, but one set was told that it was only three victims, and the other set was told that it was 30, and the three victims thought it was a more heinous crime and actually gave the perpetrators a longer prison sentence when asked.

They Align Cross-Functional Teams: Personas create a shared understanding among stakeholders such as designers, developers, product managers, and marketers. Everyone sees the same “person” and can focus on their needs.

They Reduce Costly Mistakes: Personas take time and resources to create. However, they can prevent poor, expensive decisions during development. Without personas, projects can realize too late that the product, service, or experience doesn’t meet user needs.

Personas are powerful tools when created and used correctly. However, some common misconceptions can confuse or cause skepticism among teams. These misconceptions can weaken the impact of personas or cause them to be ignored altogether. An understanding of these misconceptions can help convince wider stakeholders to adopt personas as part of the design and development process:

Personas represent everyone. Personas represent a targeted audience of users designers want to delight. When you try to create personas for every skill level or ability, it makes them uselessly vague. Designers address inclusivity and accessibility separately to their personas.

More personas mean better coverage. The opposite is true. The more personas you create, the harder it is to make decisions. Most projects need one or two primary personas and possibly a few secondary ones with slight variations.

Personas are just demographics. Demographics, such as age, job and education, provide context, but they don’t explain how people behave. Designers build effective personas with observed behaviors and motivations, not assumptions.

Marketing personas are suitable for design. Design personas are for understanding user interaction and behavior. Customer personas are for understanding purchasing habits. While both are called personas, they are not interchangeable.

Approaches and methods for building personas vary greatly between design teams. However, the following is a simple yet effective approach.

Research is the backbone of personas. Begin your persona research with qualitative methods, such as observations and interviews. Then, validate your findings with quantitative research methods, such as surveys and analytics. This approach is called triangulation and, in particular, methodology triangulation.

Reliable personas are built on reliable user research. Researchers often use grounded theory, a research approach that reduces biases and helps reveal true user needs and behaviors. In this video, William Hudson explains grounded theory.

Grounded theory is a well-known approach to qualitative research from the social and psychological research areas. It started around about the late 1960s with Glaser and Strauss, whose book, about the subject is really the original bible for it. It is research without preconceptions. It's very open in that respect. You're not trying to find out,

answers to specific questions; you're trying to find out how people behave in particular problem domains. So, for persona research, really, it's ideal. And the basic principle of grounded theory, the way that it's executed, is that researchers alternate between data collection and analysis. We go out, and we do interviews. We come back with lots of interview notes, recordings if possible, and we try to make sense of it. And that sense involves seeing how

much information overlaps between the various interviews. And if we find some areas which have scant overlap, if that area is of interest to us, we might want to go and ask about those particular areas in other interviews or even go back to the original participants and ask them to provide us with a bit more information on that. I've certainly done that, discovered new things

later on, and gone back and spoken to participants again about those new topics to find out whether those were of interest or were involved in their own dealings in that particular problem domain.

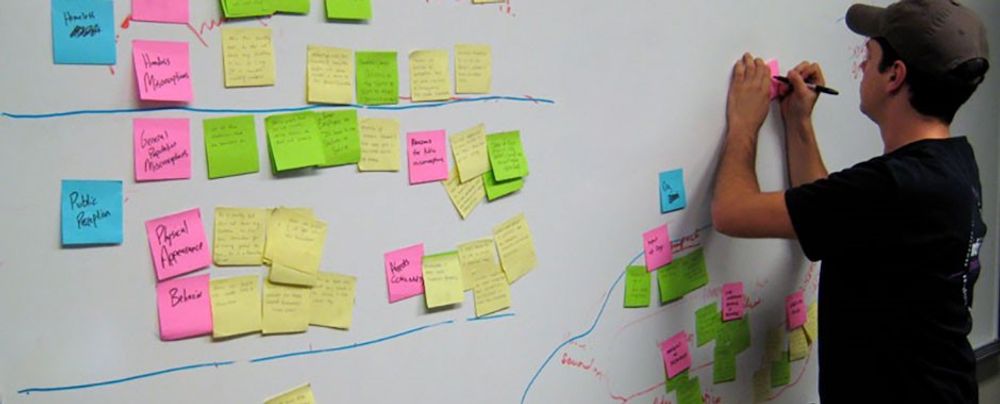

To make sense of your data, you can use affinity diagramming—an effective and collaborative tool for making sense of research data. Begin this approach by writing affinity notes which you will later arrange into an affinity diagram. In this video, William Hudson explains how to create affinity notes from user research.

The affinity diagramming process involves a number of components, the most basic of which is the set of affinity notes. These are the original user observations, and I say "original" but not literally; they actually are taken from user observations, but they're written in the first person, which we call "voice of the customer," and they're always in the first person and always in the voice of the customer.

And of course, people don't normally always talk like that, so you'll find yourself having to, transcribe them, either in the field or, if you've taken recordings, you might transcribe them later. It's always a lot of people, it's tiring, you know, it's so even that gets exhausting. So I try to keep it like one hour max, one and a half, like a bigger shopping. We try to avoid that. We try to avoid days that we know it's gonna or hours that we know it's going to be

like really packed. When I did take interview notes in the field, I did it on a small laptop, and I would deliberately write these in the appropriate format, so they would be in the first-person voice of the customer, and if I thought there was any chance that the interviewee might have meant something different, I'd read it out to them, and I'd say, "Is that a fair representation of what you've just said?" And they would usually agree. Occasionally, they'd say,

"Well, no, it was more like something else." So, it's good to make sure that you actually check this data with your original interviewees. For the remote sessions, I did recordings and had that transcribed into text and then turned that into voice of the customer and then sent those files back to the interviewees just to ask them to have a run through and make sure that everything there was what they'd said, and they were happy with it. So, that just makes sure that we're still on the same page in terms of what user said and what we actually, wrote down.

A key method to promote empathy with the research data is to record what users say and do in first-person notes. This is also known as “voice of the customer.” Voice of the customer notes should be:

Specific and behavioral.

Short enough to fit on a sticky note.

Written during the research session or transcribed from recordings.

The voice of the customer helps stakeholders immerse themselves in the research data. For example, instead of writing, “Julia crosses items off her list as she puts them in her basket,” you would write, “I cross items off my list as I put them in the basket.”

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Once you have completed your research with grounded theory and recorded your qualitative data on affinity notes, you can begin your affinity diagram.

In affinity diagramming, you group related notes into themes and reveal patterns in user behavior. This collaborative approach helps immerse stakeholders in the research data. When you build personas in collaboration with stakeholders, they are much more likely to relate to and benefit from them. Immersion and collaboration result in products, services, and experiences that align with user needs.

In this video, William Hudson explains how to create affinity diagrams.

The affinity diagramming process starts with the basic affinity notes that we obtain from user interviews and adds multiple layers of hierarchy effectively. Karen Holtzblatt suggests three. So, you and your colleagues go through all the observations, all the affinity notes, group things that you think are related for whatever reason together, and then you would put a blue note on top of those to indicate that those are connected

and try to describe, again in the voice of the customer, what that affinity is, why those particular things are similar. On top of that, you might repeat the process with pink, and those, not surprisingly, group together the blue themes. And then finally, on top, you have a green layer. Now, the green layer may or may not be in the voice of the customer; by that stage, you're actually quite happy just to summarize. But at the pink and blue layers,

if you have both of those, it's not absolutely essential, it's important that you don't misrepresent the notes underneath. So, summarizing is generally not a good idea at the lower levels. We actually need to be, much more detailed in describing the notes underneath, as it were. If you're doing an affinity diagramming activity face to face, you'll be doing it in a large room, large enough to accommodate all the team members for the process. And those team members there,

beyond your original project team, might include other stakeholders or managers in the organization, might include people from your marketing department, for example, but the people who can contribute and who are interested in what your users say and do and to help shape the direction that your product or service is going to take. So, you have this, this in theory, large room with a fairly large number of people in it, and you need to distribute now these observation notes that you took from your research and turn them into affinity notes

by making them first person, and you shuffle those. It's important that you shuffle them because otherwise you could end up giving handfuls of the same participants to a very small number of people. People are asked to put the affinity notes either down on the table if you're doing it horizontally and they're just plain notes or up on the walls if you're using post-it notes or something similar. And then you start to organize them and reorganize them and label them.

Now, the curious thing is the choice of colors. It turns out that you can buy packs of post-it notes from various manufacturers in these four colors: the yellow affinity notes and then pink, blue, and green. So, that's handy. I don't know whether that was behind Karen's original choice of colors for these things, but it's extremely convenient. You may end up doing this incrementally, so you might actually have several sessions. You would do that with new data when it arrives, and this is actually a recommended procedure, especially

in new problem areas where you're not entirely sure what you're going to find out, but you might still have a lot of data. So, you have an initial session and then you add to it in a subsequent session. Obviously, it's quite a different process for doing it online, but this is the summary of how you do it when you're in a physical face-to-face situation.

In affinity diagramming you:

Group notes into clusters based on similarities.

Label the levels nearest the original notes with accurate summaries of the grouped notes.

Label the top level of notes with summary categories, such as “paint points” or “goals.”

Identify key patterns that describe distinct user behaviors and needs.

Once you have your affinity diagram insights, you can create your persona. One approach is to create a Minimal Viable Persona (MVP). An MVP contains the ideal amount of information you need to promote empathy with stakeholders without overwhelming them with information. A minimal viable persona should contain:

A name and specific age, since real people do not have age ranges.

Roles (if this persona has more than one)

A photo, preferably from one of your research participants. Stock photos with models make personas less credible.

Primary goals, behaviors, and motivations.

Brief backstory relevant to the problem domain.

Pain points, quotes, and other helpful information.

If your team needs a deeper emotional connection with your persona, you can add a more detailed backstory. For example, this may be required if you’re designing a solution for patients in a healthcare setting.

You can download our easy-to-use, fillable template to build your persona. It includes detailed instructions on what to include in each section, plus an example to inspire you.

Once design teams have created their personas, they then use them to promote empathy, align teams, and drive effective decision-making. Here’s how to integrate personas into your design process:

Use them to evaluate ideas: Ask throughout the project: “Would this feature help [Persona Name] solve their problem?” This approach ensures your decisions remain based on real user needs.

Keep them visible: Promote your personas digitally and physically. You can put them on the wall or on digital boards. You can also create t-shirts and mugs to share with your colleagues or even full-size cardboard cutouts to take to meetings.

Merchandise helps keep personas visible and front of mind within design teams.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Put them in stories of use: These include persona stories and use cases. Examples of your personas in action help you and your team understand how users will use your product, service, or experience. For example, “Amina wants to save her grocery list so she can reorder items easily.”

Revisit and update regularly: If your market, product scope, or technology changes, your personas may need updates, too. User needs and behaviors change over time, so personas must change, too.

Personas are powerful tools for designers. However, there are some key considerations and limitations to be aware of.

The first is that a persona cannot represent every skill level within your user base. Design teams consider learnability, accessibility, and usability separate from their personas. In this video, William Hudson explores how designers must approach these considerations and why personas don’t represent every user.

I'd like to use these nested dolls to talk about a common misconception about personas, and it's a longstanding misconception, so I'm almost certain you will have heard it. I'll tell you about the dolls first. These are Ukrainian nested dolls, and I'm using them, as individual personas in a hypothetical system. So, these are two primary personas. That means they have different goals, different problems they want our solution to solve for them,

they have different behaviors and needs. This one is, Darina, and this one is Sophia. But obviously, being nested dolls, there's more to them than first appearances. Now, we've revealed a different dimension to our personas, and what I'd like to do is to pretend that the size represents a combination of skills and ability. The point with personas is that we really rarely define

a persona in terms of skill and ability, and even if we did, the diverse range of all users that are going to be engaged with our products is vast. You cannot possibly represent that in a single persona. It's just not achievable. And what I'd like to do is go a little bit further into this skills and abilities idea. The skills are things that people learn by and large,

so they are to a certain extent reliant on what people already know when they come to use your solution. They also rely on them learning, so learnability is a big issue when we're talking about skills. Ability, on the other hand, not entirely unrelated to skills, but it's more to do with your innate abilities. So, here we're talking about whether people find it easy to do slightly more advanced things like double-clicking the mouse. Used to be an advanced thing,

and it still is for some people. Right-clicking is an advanced thing and was, in the early days, something that people had to get used to doing. It still is considered to be, by the way, an advanced feature. You should never put primary activities on a right mouse click if you're talking about a desktop application. But it's interesting and useful to talk about the combination of skills and abilities because they do interact. So, here, the smaller dolls are meant to represent people with

less skill and less ability, and the larger ones, more skill and ability. The point is that when you're defining a persona, you may say something about frequency of use or how experienced that particular persona is in general, but you're still not describing the whole range of frequencies of use and skills. You can't do that. That's—that's not what the persona is for. The personas are for

giving focus. So, you give some focus on skill and ability, but usually very little focus on that. The main focus is on the problems they have and the solutions you're providing. So, what are their needs and behaviors? We often say nothing about their skills and abilities, but you have a set of responsibilities. You have responsibilities to your organization to produce a successful product. You have responsibilities to your wider range of users who may not fit

your persona but are still sitting in front of your product. You don't want to make a bad user experience for them. They're just not the focus of your persona. And similarly, we might, if our persona, typical persona, is somewhere in the middle range, which it often is, and we want to make sure that we're actually targeting more expert users, or maybe our persona is more expert, we might say that in the persona they're a frequent user or they're already well experienced. Then we adjust the user interface accordingly. Weshouldn't be making it impossible for people with

less skills or experience to do what they need to do, but we might provide, for example, shortcuts, things like right mouse clicks on objects is a one very popular way of doing that. So, using personas is not intended to give you a lot of information on skills and abilities. They are separate dimensions. You need to consider those at all points, whether you're using personas or not.

The personas are there to give focus on a particular set of users, specifically a subset of your users who you want to build a solution to wow or delight, and for the rest of those users, you want to provide at least a good user experience, if not an outstanding one.

When you design for a persona, remember the following:

Make sure you don’t exclude users not represented by a persona. All users must be able to learn and use your product, service, or experience, regardless of whether they fit your persona’s profile.

Ensure compliance with accessibility standards (e.g., WCAG). For example, even if your persona isn’t visually impaired, your product must work for those who are.

Another key consideration is how many personas you should use. Small projects typically only need one primary persona. Larger projects may need more. If you need a persona for a user group that overlaps considerably with your primary persona, you can use a secondary persona. Remember, the more personas you have, the more focus you lose, and this is the primary purpose of a persona.

Learn how to research and build personas that promote empathy, align teams, and drive user-centered design in our course, Personas and User Research: Design Products and Services People Need and Want.

Discover more about cognitive empathy and why we empathize more with individuals than groups in our article, How Personas Shape Stronger Design Decisions.

Explore grounded theory for persona research in our article, Grounded Theory: Base Findings on Research, Not Preconceptions.

Take an in-depth look at persona development in Smashing Magazine’s article, A Closer Look At Personas: A Guide To Developing The Right Ones.

Find how to avoid common persona pitfalls in Nielsen Norman Group’s article, Why Personas Fail.

To create effective personas, start by researching to understand your users, focusing on their behaviors, needs, and motivations. William Hudson, CEO of Syntagm Ltd, emphasizes the significance of personas in promoting empathy and understanding, allowing designers to focus on individuals rather than abstract user groups.

Personas are representations of our *users*. They promote empathy by allowing us to focus on individuals rather than groups. It's this whole issue of empathy. We keep talking about "users". And even just talking about the *roles* like "customers" or "clerk" or "salesperson" doesn't make these roles seem real. It doesn't. We're not talking about real people. Real people have limited abilities.

Real people don't necessarily get computers in the same way that the development team does. Real people have needs that have been brought up by their circumstances or by their own personal beliefs. So, we need to know a bit *about* them. And personas are a great way of representing those understandings in the design of a real system. So, there is strong psychological evidence for *personal bias*. Our brains are wired to *empathize with individuals rather than groups*. The general feeling is that when we dehumanize people by referring to them

with these abstract collective nouns – because collective nouns *are* abstract by definition, so we're talking about "users" or we're talking about "customers" – we're taking the "people" away. We need to put the "people" back. Back in 1983, David Sears ran a study with two sets of participants. He gave the participants the same characteristics. And in one set of participants he said that these characteristics were of

*an individual*. And I believe he described the individual. And in the other set participants he said that these characteristics were of *a group of people*. And the participants who were told that they were seeing the characteristics of an individual *always rated the individual more highly* than the participants who rated the characteristics in connection with a group. So, that he called the *person-positivity bias*. And it basically is confirmation that our brains

– us as individuals – *prefer thinking about other individuals*. We're certainly more inclined to think more positively about other individuals than we are about collective nouns like "tourists" or "customers" or "users". The *scope-severity paradox* is a much more recent piece of work – 2010 – and is quite surprising. Two researchers, Nordgren and McDonnell, established that reactions to a fraud were more severe when it was presented with three victims rather than 30. So, it's the same kind of deal: two sets of participants,

both given exactly the same details of a crime, except that in one group they were told it affected three people and the other group were told it affected 30 people. And it was the people who were told that there were only three victims that thought that the crime was more severe. And they, on average, added a year on the prison sentence that the perpetrators of this crime should receive. So, again, that is just confirming this tendency for us to feel more strongly about individuals than we do about groups.

Personas are fabrications *based on research*. We mustn't let go or lose sight of that little parenthetical expression there, because we go out and we find out who these people are – the ones that we're interested in – find out what behaviors they have which drive them to need our solution, what motivations, what their circumstances are, what their contexts of use are,

just so we understand who we're building the solution for and other aspects that we describe in the context of use. These personas are representations of our users, who represent the goals, behaviors and motivations of those real users. They *promote empathy* by allowing us to *focus on individuals rather than groups*. So, instead of talking about "User Community One" or whatever catchy name we'd like to come up with for our user communities, we start talking about "Bob"

or "Jane" or "Elizabeth" – whoever – whatever everybody in the team is happy with. And there have been all kinds of documents and papers and studies written about personas. And you'll find that personas range from quite a limited description of a person. And, in fact, it can be just as little as changing the name "users" to a person's name. So, if you always refer to your customers as "Andrew", then you would actually

be doing yourselves a favor in terms of making that customer seem much more real. But at the other extreme it's not uncommon to hear about user research and persona development taking *weeks* – possibly even months: 2–3 months, which is, in my view and and quite a few others', certainly for an Agile environment well beyond the realms of possibility. So, we're going to be talking about something called a *minimal persona*. So, minimal persona – a name, age and other specific demographic details that a real person

would have. A photo – ideally realistic – showing the person in that setting or doing that thing. And then, basic information about why you're interested in them or why they're interested in us – our solution or product. So, their *primary goals*: *why* those are their primary goals and *what* they're hoping to achieve through our solution or product. And their *behaviors* – what are they doing before and after interaction with our solutions

fit with their daily routine, for example. And some of this comes from the fact that I have for years been astounded by how little the people developing software solutions know about their users. I've been involved in a couple of projects where there was no contact whatever. The development team had never met or seen a user, didn't know what the user was doing immediately prior to entering or receiving data from their system, didn't know what happened to the output data, knew almost nothing.

So, it wasn't surprising that the system when it was first launched was almost impossible to use, because it didn't actually fit. It was like having a random piece of a jigsaw puzzle and a very well-defined hole that it just did not slip into. So, these are the reasons we're trying to actually make sure that we understand at least something about our user communities. And that's what personas are trying to help us with. *Extended personas* – you might add lifestyle interests,

hobbies, as they apply to their motivations. I wouldn't add them just to make the person seem more complete. That isn't absolutely essential. But if some of those issues – lifestyles, interests or hobbies have an impact on your solution, then you should know about them. So, *keep to the details that are relevant* to the problem. Remember that we want to *motivate our team to help* our personas, *not* to drive them crazy with distracting detail, which is one of the complaints you will hear about personas.

Certainly when I've attended conference research papers on the use of personas in teams, often they were not well-received, because there just seemed to be so much of it – the persona specification. *Credibility*: ensure that the personas are *believable* and liked *as much as possible*. Certainly do *not* give personas unpleasant or dubious habits like being a heavy drinker or a heavy smoker or likes to bet on the horses – unless, of course, you're building a gambling app or something! *Change the name, photo and other details* until the whole team is comfortable with them.

It needs to be a collaborative effort between the user experience people and the people who are going to be using them. That would be the development team. So, the names and the photos are almost entirely arbitrary. If you've done research with a handful of participants, then you'd have a handful of photos. If not, then try to find photos from a stock photo site. But try to avoid overtly attractive people because it can be distracting. In user experience, we create often what are referred to as "design research personas",

or "design personas" for short. So, that's what these things are technically called. We go out and we research these user communities. We decide what behaviors and needs are relevant to us: Who are we building the solution for? And those personas are based on this design research. So, that's why we want to call them "design research personas" or "design personas". But there are lots of other things that also get tagged with personas.

And the most common of those I've come across, particularly in large companies, are *market research personas*. And they're not the same thing is the main problem that we have. So, beware that *other kinds of personas exist*, often based on demographics or market segmentation. These can be used for *validating design personas, but should never replace them*. There is little point in trying to reuse personas for different projects, as well, unless the same goals, motivations and behaviors are relevant.

And I've come across this whole approach in one particular vertical market in the U.K. And that is mobile phone service providers – that they have all got marketing personas based on age ranges. And they then attach labels to these age ranges to suggest how these people behave and what they need from our services, which, just to be honest, cannot really be true! You need to actually *forget about the demographics*. There will be some age-related behaviors, no doubt. But they shouldn't be

the motivating factors in the design of an interactive system, which is, after all, what we're trying to achieve. The main thing is that predominantly you have *one* or *two* primary personas. If you've got a project – and I've had people kind of come up to me almost in a boasting tone, saying: "Our project has got 20–30 personas!" And I'd say, "Oh, really? How is that?" They'd say, "Well, it's a hospital system." And the thing is, it's a *very* big system. And what you need to make it agile and to make these things work effectively

is to split the system into parts. So, you may well have some small number of primary personas that apply throughout. But in many cases you're going to have primary personas that are specific to that kind of system or that part of a system. So, let me give you some very simple examples. The one that I like to use is a hotel self-check-in. When I started writing about hotel self-check-ins, there were none in existence. And now I do come across them, funnily enough, in hotels that have got receptionists but all they do then is to

refer you to the self-check-in in front of the reception! I was motivated for this example by checking in at a conference hotel on one occasion. I actually got in pretty easily. I think it was a 20- or 30-minute process. But the next day I was walking through the reception and the queue – the line – of people waiting to check into this hotel went around the block. It was just utterly amazing. There must have been 200 or 300 people waiting to get in.

So, it occurred to me: "Well, why don't we just have some self-check-ins like we do at airports?" And, of course, self-check-in at airports is entirely bog-standard these days – it's what everyone does. So, for example, the primary persona of a hotel self-check-in service must be the customer checking in. It makes no sense for it to be otherwise. A *secondary persona* would be someone who is acting in a *supporting role* inside that system. So, a secondary persona might be a hotel manager or a receptionist or somebody who's

responsible for the upkeep of the hotel, for example. So, these are all *secondary roles*. They're not the people for whom we are building the system. They are people who are *involved in* the system and often in a backroom kind of interaction. These are people that primary personas rarely see or even know about. So, it's a difference between the primary roles in a stage production and just extras or people with non-speaking parts. That is kind of the difference between primary and secondary personas.

A lot of systems may have *only one* persona. This is the person that we're building this particular product for. And you can have all kinds of philosophical arguments about whether you're building a Swiss Army knife solution or whether you're building a carving knife solution. One is very good at one thing. Carving knives are very good at carving. Swiss Army knives are very good, but in a fairly different kind of way, at *all kinds* of things.

But they're not all that easy to use. So, it's up to you. The whole point of personas is to try to *give focus*. So, these are our customers. Other people, who do not fall into the definition or the descriptions of our personas, it's fine if they find our system easy to use. But unless we can actually identify some clear purpose in adapting the system to be more inclusive, then we would deliberately not pay much attention to their particular requirements. Now, things like *accessibility* and the *age ranges* of users – they fall outside the whole persona mechanism.

You must *always make sure that your systems are usable by those with disabilities* whether that's acknowledged specifically in your persona or not. I do have at least one colleague who, if they're dealing with a team who has little experience of accessibility – that is, systems that will be used by disabled people – he deliberately includes a disabled persona. But that really ought not to be necessary. But if that works for you, then that's absolutely fine, too.

Certainly I can see it being important when working with teams that don't have much experience. So, you must make sure that your solutions work for a *broad range of people* in terms of *accessibility* and *age issues*. But otherwise, we want to be very focused on the *specific behaviors* and *needs* of our primary personas. So, we stick to small numbers to maximize empathy. And we consider splitting larger projects, as I was discussing for the hospital example. For example, a hotel check-in system could be split into front desk and housekeeping projects

with separate personas. So, those could be two smaller Agile projects. And there is no magic number. But, like I have been saying, 1 or 2 primary personas is perhaps the most common, with maybe a few secondary personas thrown in, as well. Personas get used in all sorts of places. Obviously, their main focus is in *design*. So, "Who are we building this product for? How should the interactions take place? How much experience can we rely on them having of this kind of solution?" and so forth.

We will have to *recruit* these people. We want to do *research* with them, perhaps continuing research over several life cycles of the system. We want to recruit people for usability testing and user evaluation / usability evaluation in general, not just running them through early beta releases of the software. We might want to be testing with paper prototypes. We might be wanting to show them just wireframes and talking to them about the layout

and their understanding of the different components of the page and those sorts of issues. Sales and marketing will want to know *who* they should be targeting in terms of what the system does and for whom. And remember that you will need to describe the *demographics* and the *filtering questions* for your personas to a recruiter. So, when you're recruiting "Arthurs", what is it about Arthur that makes him your persona? It needs to be something that he wants or needs or you're *hoping* that he wants or needs. He needs a solution to a problem. So, what is that problem?

So, you need to actually talk to your recruiters about filtering questions. You know, what are you going to ask *potential Arthurs* that's going to help you to decide whether this person is really an Arthur? Now, this is quite an interesting area. And it may depend a lot on how enthusiastic your team is about personas. If you've done your job right, if you've *sold* personas, or if your team is already quite familiar and quite enthusiastic about personas,

then you might do some really fun things like getting mugs and coasters printed with maybe the face of the persona on one side and some of their relevant details with respect to your system on the other side. Ditto with mugs, maybe even T-shirts. And one thing that I was quite amused by – and I could actually see this working for some teams – is life-size cardboard cutouts. That's another possibility. So, you could actually have a room with your personas kind of standing around in unused corners.

I do know of organizations – I have heard of organizations – that would actually give the persona a desk, particularly if they were building a system for somebody in-house. And they might actually put all the stuff to do with that persona on the desk, just to make that person seem more real – you know. "Arthur would always be on holiday, but there's his desk" kind of thing. And I should mention – I'll just point out this very last thing – because it's quite important: at the very least, personas should appear in *easy-to-read* form on the project workspace

– whatever – sometimes, you'll hear this phrase – I used to hear it; I don't know that I've heard it very often – called "information radiators". Well, they're what you and I might refer to as "walls" or "partitions". They're the vertical spaces in your workspace. And you would pin important things to that, like all of the backlog for the next cycle and the design maps. So, these are things which everybody who's working on the project would actually be able to refer to quite readily. You might even hand these out in laminated plastic form,

just so everybody has easy access to them, for example.

Images

Copyright holder: Benoît Prieur. Appearance time: 10:32 - 10:36 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 4.0. Modified: No. Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Avenue_Berthelot-_machine_pour_entrer_dans_l%27h%C3%B4tel.jpg

According to William, personas are fabrications based on thorough research and should represent real users' goals, behaviors, and motivations. Developing minimal personas with crucial details can be advantageous, concentrating on primary objectives, behaviors, and context of use relevant to the solution or product. It's critical to maintain credibility, ensuring personas are believable and avoiding unnecessary, distracting details.

Here's a step-by-step guide on how to create effective user personas, plus a downloadable template:

Everyone who is going to use the personas should be involved in making them. This builds a feeling of ownership and approval. Invite members of your development team to sit in on research sessions. This way, you can ensure that the personas are based on real user data and reflect the needs and goals of your target users. You can also use the personas as a communication tool to align your team and stakeholders on the user-centered design process.

Use our step-by-step guide to create user personas:

A good persona is grounded in user behavior observed through field studies, not merely opinions from surveys or focus groups. According to Frank Spillers, CEO of Experience Dynamics, in his insightful video, constructing personas requires understanding users' environments, tasks, and the context in which they consume content.

So, you've gone out, you've talked to your users. You've done a field study, basically interviews, user interviews and observations of their tasks, of their environment. And what do you do with that? Personas and journey maps. So, I just wanted to talk a little bit about personas in particular. Journey maps are also important, but I'm just going to cover personas. Where you get your data from is hugely important. Most people just use surveys.

Some people use focus groups. Those are both market research techniques. They're not appropriate for UX. Why? Because in UX we're looking at *behavior*, not at opinion. And focus groups and surveys do a lot of opinion elicitation. They're fine for marketing, but they really have no place in UX. So, if you do market research and just use like a segmentation approach or market research approach, you're going to end up with a different type of persona.

So, if you do field studies, you'll end up observing their behavior and then creating behavioral profiles or role-based personas, and you'll understand better the context and the conditions under which your mobile app or device mobile content is being consumed. And that's super important. This is an example of a persona, and you can adjust a persona. But basically you have a scenario. I've started writing my personas in first person.

So, literally the notes I take, I'll build the persona based on actually what the user said. And it's about 98% verbatim, like what they said with a few corrections of – you know – grammar and stuff like that. I won't change the meaning. I won't remove the words from their mouth and rephrase them in my head. I won't alter or fabricate them. And it's a technique that I learned from Whitney Quesenbery, a UX consultant

who's written a book about storytelling and personas in particular, because personas are really about *stories*; they're really about telling stories about that context. Try it right now. So, think about the personas that might, the roles that people, the problems they might solve with your app. And in a narrative kind of style, write one or two sentences on their background to kind of set the context; write two or three more sentences on the problems that they're trying to solve, like the tasks, and two or three sentences on the call to action,

like what they need, what their desires are or how the design can basically help them get to their task, how can it empower them? How you can meet their needs, their goals, their tasks, their sub-tasks? If you have a lot of questions, it's probably because you need to spend more time with your users. Once you start hanging out with users doing field studies, you get to know what they need and the context of use becomes very apparent.

It's one of the most enlightening things I think about personas. But also you understand their *distractions*, their deeper kind of emotional and social context. You understand what multi-tasking they might be doing and what problem solving or the different states, the varied states that they might use, kind of usage scenarios, if you will, but in different states. So, to create a role-based persona, identify the personas based on your data, so the themes that come out, the different hats that users are trying to wear.

And then give them a name, like not just like Sally or Susan or Jim or John or something. But give them an associating adjective such as Support-Seeker Sally or Finance Fiona, I think was that other one there. Okay, so continuing with persona development, think about these things: *environmental impact*, so the context of use; *cognitive impact*, the time, for example, the time pressure or stress that they might be under.

Think of the *social impact* – the triggers that might lead to that such as another user or somebody else online or started a chat or tripped off – I don't know – a support call or whatever. And finally the *behavioral impact* – so, for example, the roles that not just the user has but the roles that the user must assume to complete the task. There's also *mental models*. So, mental models being these past expectations

that users bring to their designs; they basically influence how a user problem solves. And think about like the mental model for the restaurant experience – you know – what does that look like? For example, you enter the restaurant; there might be waiting, you might have to check in, you may have to order ahead, you might have a pickup situation. Some restaurants have made a separate place for the food delivery people to go

so that they're not standing there waiting with the the diners that are coming to the restaurant for the "live food". You can conduct *task analysis*, which is asking the user to do the task. You know – you can accompany them, a doctor's visit, restaurant visit, whatever it might be. You can accompany the user and look for the language they use, the way they talk about it, look at the physical, social environment, look at their functional needs and priorities and maybe even the cognitive demands that they have.

So, for example, they have to figure something out; they have to fill in a form. They have to submit this. There's a pressure to answer these questions or to know something. Look at the task space, how they're making sense of things, how they're deciding or solving problems for themselves. Remember, we don't just have goals and tasks, but we have *sub-tasks* as well. So, we need all three of those things, not just goals. It's so important that we make sure that we drill deeper down

into our users' behavior so we fully understand what it is and bring that out. So, doing that, though, is so well worth it and makes you a much smarter designer and a much smarter design team.

Personas should be developed from user research, highlighting users' needs, goals, and the problems they encounter. A well-crafted persona describes users’ needs and behaviors as they apply to the solution in question. Backstories should focus on the motivations for the needs and behaviors, making the persona concise and directly relevant to the development team. Team engagement with personas will help to ensure truly user-centered solutions.

No, a persona is not typically a real person. It's a rich, detailed representation of user research to help understand users’ needs, behaviors, and goals. As Alan Dix, an HCI professor, emphasized in his insightful video, the persona should feel authentic and detailed to guide the design process effectively.

Personas are one of these things that gets used in very, very many ways during design. A persona is a rich description or description of a user. It's similar in some sense, to an example user, somebody that you're going to talk about. But it usually is not a particular person. And that's for sometimes reasons of confidentiality.

Sometimes it's you want to capture about something slightly more generic than the actual user you talked to, that in some ways represents the group, but is still particular enough that you can think about it. Typically, not one persona, you usually have several personas. We'll come back to that. You use this persona description, it's a description of the example user, in many ways during design. You can ask questions like "What would Betty think?"

You've got a persona called / about Betty, "what would Betty think" or "how would Betty feel about using this aspect of the system? Would Betty understand this? Would Betty be able to do this?" So we can ask questions by letting those personas seed our understanding, seed our imagination. Crucially, the details matter here. You want to make the persona real. So what we want to do is take this persona, an image of this example user, and to be able to ask those questions: will this user..., what will this user feel about

this feature? How will this user use this system in order to be able to answer those questions? It needs to seed your imagination well enough. It has to feel realistic enough to be able to do that. Just like when you read that book and you think, no, that person would never do that. You've understood them well enough that certain things they do feel out of character. You need to understand the character of your persona.

For different purposes actually, different levels of detail are useful. So I'm going to sort of start off with the least and go to the ones which I think are actually seeding that rich understanding. So at one level, you can just look at your demographics. You're going to design for warehouse managers, maybe. For a new system that goes into warehouses. So you look at the demographics, you might have looked at their age. It might be that on the whole that they're older. Because they're managers, the older end. So there's only a small number under 35. The majority

are over 35, about 50:50 between those who are in the sort of slightly more in the older group. So that's about 40 percent of them in the 35 to 50 age group, and about half of them are older than 50. So on the whole list, sort of towards the older end group. About two thirds are male, a third are female. Education wise, the vast majority have not got any sort of further education beyond school. About 57 percent we've got here are school.

We've got a certain number that have done basic college level education and a small percentage of warehouse managers have had a university education. That's some sense of things. These are invented, by the way, I should say, not real demographics. Did have children at home. The people, you might have got this from some big survey or from existing knowledge of the world, or by asking the employer that you're dealing with to give you the statistics. So perhaps about a third of them have got children at home, but two thirds of them haven't.

And what about disability? About three quarters of them have no disability whatsoever. About one quarter do. Actually, in society it's surprising. You might... if you think of disability in terms of major disability, perhaps having a missing limb or being completely blind or completely deaf. Then you start relatively small numbers. But if you include a wider range of disabilities, typically it gets bigger. And in fact can become

very, very large. If you include, for instance, using corrective vision with glasses, then actually these numbers will start to look quite small. Within this, in whatever definition they've used, they've got up to about 17 percent with the minor disability and about eight percent with a major disability. So far, so good. So now, can you design for a warehouse manager given this? Well,

you might start to fill in examples for yourself. So you might sort of almost like start to create the next stage. But it's hard. So let's look at a particular user profile. Again, this could be a real user, but let's imagine this as a typical user in a way. So here's Betty Wilcox. So she's here as a typical user. And in fact, actually, if you look at her, she's on the younger end. She's not necessarily the only one, you usually have several of these. And she's female as well. Notice only up to a third of our warehouse ones are female. So

she's not necessarily the center one. We'll come back to this in a moment, but she is an example user. One example user. This might have been based on somebody you've talked to, and then you're sort of abstracting in a way. So, Betty Wilcox. Thirty-seven, female, college education. She's got children at home, one's seven, one's 15. And she does have a minor disability, which is in her left hand. And it's there's slight problem in her left hand.

Can you design, can you ask, what would Betty think? You're probably doing a bit better at this now. You start to picture her a bit. And you've probably got almost like an image in your head as we talk about Betty. So it's getting better. So now let's go to a different one. You know, this is now Betty. Betty is 37 years old. She's been a warehouse manager for five years and worked for Simpkins Brothers Engineering for 12 years. She didn't go to university, but has studied in her evenings for a business diploma.

That was her college education. She has two children aged 15 and seven and does not like to work late. Presumably because we put it here, because of the children. But she did part of an introductory in-house computer course some years ago. But it was interrupted when she was promoted, and she can no longer afford to take the time. Her vision is perfect, but a left hand movement, remember from the description a moment ago, is slightly restricted because of an industrial accident three years ago.

She's enthusiastic about her work and is happy to delegate responsibility and to take suggestions from the staff. Actually, we're seeing somebody who is confident in her overall abilities, otherwise she wouldn't be somebody happy to take suggestions. If you're not competent, you don't. We sort of see that, we start to see a picture of her. However, she does feel threatened – simply, she is confident in general – but she does feel threatened by the introduction of yet another computer system. The third since she's been working at Simpkins Brothers. So now, when we think about that, do you have a better vision of Betty?

Do you feel you might be in a position to start talking about..."Yeah, if I design this sort of feature, is this something that's going to work with Betty? Or not"? By having a rich description, she becomes a person. Not just a set of demographics. But then you can start to think about the person, design for the person and use that rich human understanding you have in order to create a better design.

So it's an example of a user, as I said not necessarily a real one. You're going to use this as a surrogate and these details really, really matter. You want Betty to be real to you as a designer, real to your clients as you talk to them. Real to your fellow designers as you talk to them. To the developers around you, to different people. Crucially, though, I've already said this, there's not just one. You usually want several different personas because the users you deal with are all different.

You know, we're all different. And the user group – it's warehouse managers – it's quite a relatively narrow and constrained set of users, will all be different. Now, you can't have one persona for every user, but you can try and spread. You can look at the range of users. So now that demographics picture I gave, we actually said, what's their level of education? That's one way to look at that range. You can think of it as a broad range of users.

The obvious thing to do is to have the absolute average user. So you almost look for them: "What's the typical thing? Yes, okay." In my original demographics the majority have no college education, they were school educated only. We said that was your education one, two thirds of them male – I'd have gone for somebody else who was male. Go down the list, bang in the centre. Now it's useful to have that center one, but if that's the only person you deal with, you're not thinking about the range. But certainly you want people who in some sense

cover the range, that give you a sense of the different kinds of people. And hopefully also by having several, reminds you constantly that they are a range and have a different set of characteristics, that there are different people, not just a generic user.

It enables creators to ask targeted questions like "How would this persona use this feature?" to optimize user experience.