The 5 Stages in the Design Thinking Process

- 2k shares

- 1 mth ago

Problem statements are concise descriptions of design problems. Design teams use them to define the current and ideal states, and to freely find user-centered solutions. Then, they use these statements—also called points of view (POVs)—as reference points throughout a project to measure the relevance of ideas they produce.

“If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”

— Albert Einstein

Well-constructed, valid and effective problem statements are vital for your design team to navigate the entire design process. Essential to design thinking, problem statements are what teams produce in the Define stage. To find the best solutions, your team must know what the exact problems are—i.e., you first need to define a problem statement.

The goal is to articulate the problem so everyone can see its dimensions and feel inspired to systematically hunt for suitable solutions. When you unite around a problem statement, your team will have a common view of how users see what they must tackle. From there, all your team will know exactly what to look for and what to avoid. Therefore, you should make your problem statements:

Human-centered: Frame problem statements from insights about users and their needs.

Have the right scope:

Broad enough to permit creative freedom, so you don’t concentrate too narrowly on specific methods for implementing solutions or describing technical needs; but

Narrow enough to be practicable, so you can eventually find specific solutions.

Based on an action-oriented verb (e.g., “create” or “adapt”).

Fully developed and assumption-free.

Design teams sometimes refer to a problem statement as a “point of view” (POV) because they should word problem statements from the users’ perspective and not let bias influence them. Your team will have a POV when it comes up with a narrowly focused definition of the right challenge to pursue in the next stage of the design process.

With an effective POV, your team can approach the right problem in the right way. Therefore, you’ll be able to seek the solutions your users want.

To define a problem statement, your team must first examine recorded observations about users. You must capture your users’ exact profile in the problem statement or POV. So, you need to synthesize research results and produce insights that form solid foundations. From these, you can discover what those specific users really require and desire—and therefore ideate effectively.

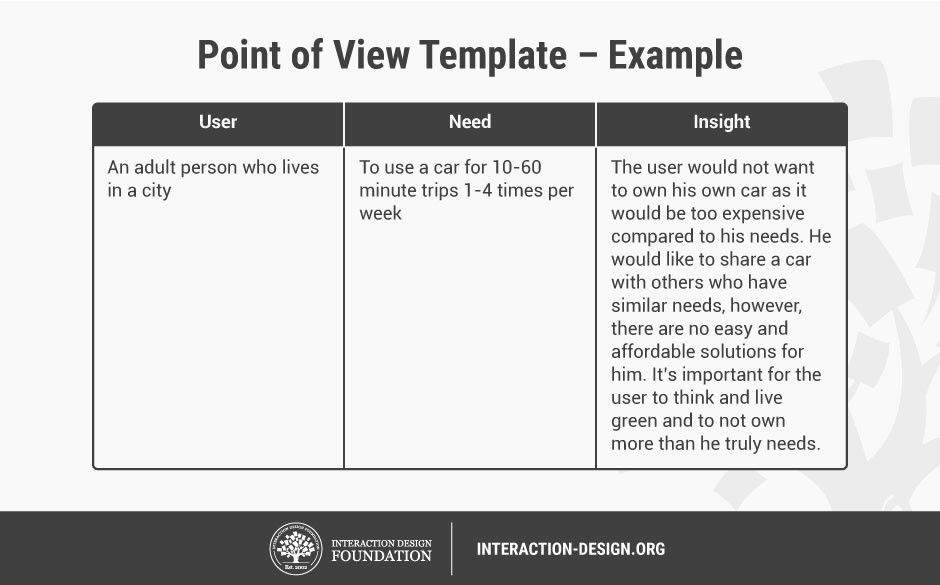

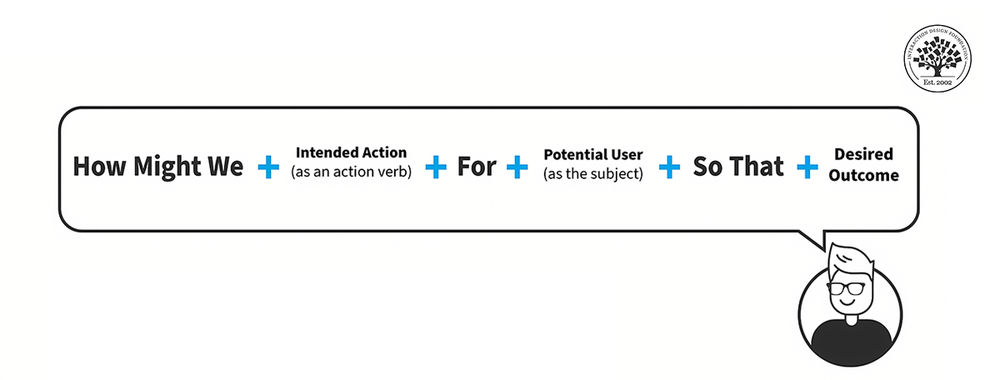

Teams typically use a POV Madlib to reframe the challenge meaningfully into an actionable problem statement. The POV madlib is a framework you use to place the user, need and insight in the best way. This is the format to follow:

[User… (descriptive)] needs [need … (verb)] because [insight… (compelling).]

![Point of view Madlib, which reads as: [user] needs to [user's need] because [insight].](https://public-images.interaction-design.org/tags/dovP15BeMdoWhNxAkIhOyu0iLoB7PpJpByqvZ37i.jpg)

You articulate a POV by combining these three elements—user, need, and insight—as an actionable problem statement that will drive the rest of your design work. Find an example below.

With a valid problem statement, your team can explore the framed “why” questions with “how”-oriented ones. That’s how you proceed to find potential solutions. You’ll know you have a good problem statement if team members:

Feel inspired.

Have the criteria to evaluate ideas.

Can use it to guide innovation efforts.

Can’t find a cause or a proposed solution in it (which would otherwise get in the way of proper ideation).

When your team has a good problem statement, everyone can compare ideas, which is vital in brainstorming and other ideation sessions. It also means everyone can keep on the right track. Problem statements are powerful aids because they encourage well-channeled divergent thinking.

Rather than rush toward solutions that look impressive but aren’t effective, your team can work imaginatively to find the right ones. Once you’ve discovered what’s causing problems, you can give users the best solutions in designs they like using.

Take our course addressing problem statements.

See d.school’s illustrations of problem statements in action.

Explore Toptal’s example-rich examination of problem statements.

This piece exposes the practicalities of problem statements for startups.

Here’s a thought-provoking approach to problem statements.

Keep in mind that a strong problem statement clearly defines an issue, why it matters, and who it affects֫—and so it’s best to be specific, focused, and actionable.

Start by identifying the problem. Don’t use vague or broad descriptions. Instead of “Users struggle with our app,” say “New users find the checkout process confusing, leading to a 40% drop-off rate.”

Next, explain why the problem matters and show its impact on users, business goals, or efficiency. Things like “If customers abandon their carts, the company loses revenue and users become frustrated.”

Then, define who experiences the problem—and remember that a strong statement focuses on a specific group, not the faceless (and useless!) “everyone.”

Finally, don’t suggest solutions too early. Keep within the “problem space.” A problem statement should guide research and brainstorming, not limit options.

Here’s an example of a good problem statement:

"Young professionals using our budgeting app struggle to track daily expenses because of a cluttered interface, leading to frustration and a 30% drop in engagement within a week."

Watch as UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains important points about brainstorming:

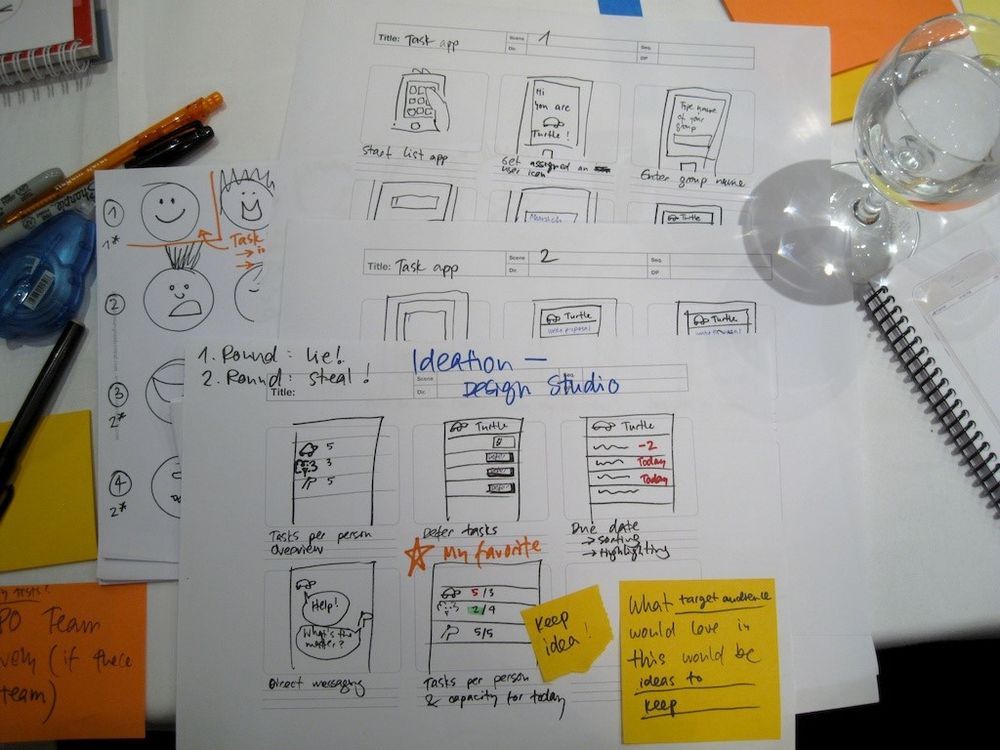

Brainstorming is a group activity where people come together to share ideas and think creatively to solve problems or generate new concepts. The goal is to encourage free thinking and creativity without judgment or criticism, allowing participants to share any idea that comes to mind no matter how unconventional or seemingly impractical. The aim is to *spark creativity and explore various possibilities* which can later be refined or combined to develop more practical or innovative solutions.

Brainstorming sessions often involve structured or unstructured discussions, note-taking or visual aids to capture and organize the ideas generated by the group. So, how can you structure a brainstorming session? Define the goal. Clearly outline the problem or objective. Create a diverse group. Gather people with varied perspectives. Encourage participation and free thinking. Generate ideas without criticism. Build on ideas. Combine, refine or expand on suggested thoughts. Set a time limit. Keep the session focused and efficient.

And lastly, document and evaluate. Record all ideas and assess their feasibility later. You can spend some time after the session to categorize, reduce and analyze.

A strong problem statement has four key elements to it:

The Problem—Clearly describe what’s wrong and don’t use vague phrases. Instead of “Users dislike the app,” say “Users struggle to complete the checkout process, causing a 40% drop-off rate.”

Who It Affects—Identify the specific group experiencing the problem; so, instead of saying “Everyone has trouble,” define the audience: “First-time users on our e-commerce site.”

Why It Matters—Explain the impact. For instance, does it lower sales? Cause frustration? Waste time? Example: “This issue leads to lost revenue and poor user retention.”

The Context—Provide background or relevant data; so, if users drop off after step three of checkout, include that detail.

Example:

"New customers on our website struggle with the checkout process because of unclear navigation, causing a 40% drop-off rate and $50,000 in lost monthly revenue."

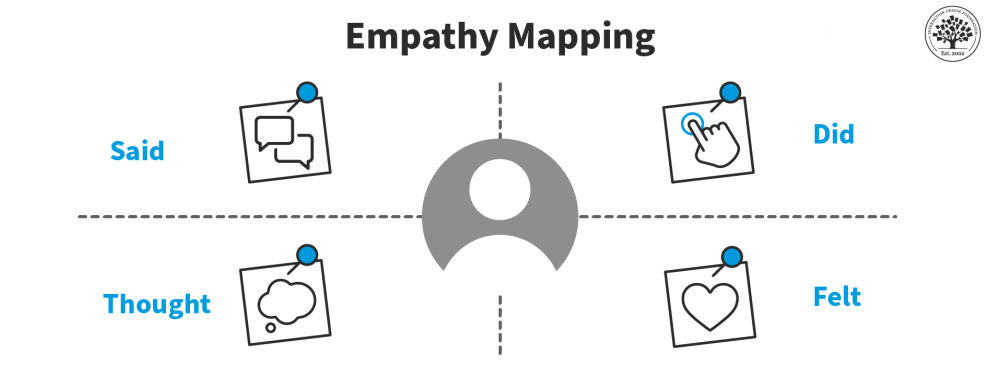

Overall, a problem statement should be specific, measurable, and focused to guide effective solutions—and one of the keys to the enterprise is a strong sense of empathy.

Watch our video on empathy to understand more about why it’s vital in design:

Do you know this feeling? You have a plane to catch. You arrive at the airport. Well in advance. But you still get stressed. Why is that? Designed with empathy. Bad design versus good design. Let's look into an example of bad design. We can learn from one small screen.

Yes, it's easy to get an overview of one screen, but look close. The screen only shows one out of three schools. That means that the passengers have to wait for up to 4 minutes to find out where to check in. The airport has many small screenings, but they all show the same small bits of information. This is all because of a lack of empathy. Now, let's empathize with all users airport passengers,

their overall need to reach their destination. Their goal? Catch their plane in time. Do they have lots of time when they have a plane to catch? Can they get a quick overview of their flights? Do they feel calm and relaxed while waiting for the information which is relevant to them? And by the way, do they all speak Italian? You guessed it, No. Okay. This may sound hilarious to you, but some designers

actually designed it. Galileo Galilei, because it is the main airport in Tuscany, Italy. They designed an airport where it's difficult to achieve the goal to catch your planes. And it's a stressful experience, isn't it? By default. Stressful to board a plane? No. As a designer, you can empathize with your users needs and the context they're in.

Empathize to understand which goals they want to achieve. Help them achieve them in the best way by using the insights you've gained through empathy. That means that you can help your users airport passengers fulfill their need to travel to their desired destination, obtain their goal to catch their plane on time. They have a lot of steps to go through in order to catch that plane. Design the experience so each step is as quick and smooth as possible

so the passengers stay all become calm and relaxed. The well, the designers did their job in Dubai International Airport, despite being the world's busiest airport. The passenger experience here is miles better than in Galileo Galilei. One big screen gives the passengers instant access to the information they need. Passengers can continue to check in right away. This process is fast and creates a calm experience,

well-organized queues help passengers stay calm and once. Let's see how poorly they designed queues. It's. Dubai airport is efficient and stress free. But can you, as a designer, make it fun and relaxing as well? Yes.

In cheerful airport in Amsterdam, the designers turned parts of the airport into a relaxing living room with sofas and big piano chairs. The designers help passengers attain a calm and happy feeling by adding elements from nature. They give kids the opportunity to play. Adults can get some revitalizing massage. You can go outside to enjoy a bit of real nature.

You can help create green energy while you walk out the door. Charge your mobile, buy your own human power while getting some exercise. Use empathy in your design process to see the world through other people's eyes. To see what they see, feel what they feel and experience things as they do. This is not only about airport design. You can use these insights when you design

apps, websites, services, household machines, or whatever you're designing. Interaction Design Foundation.

A problem statement should be short and clear. “Short” is usually one to three sentences. “Clear” means it needs to explain the problem, who it affects, and why it matters without adding unnecessary details.

If it’s too long, the main point gets lost; if it’s too short, it might lack clarity or impact. A good length is 50 to 100 words, enough to define the issue without suggesting solutions. It’s best to keep a focused view of it as a tool that helps a great deal in design thinking.

Example:

"First-time users struggle with our app’s navigation, leading to a 40% drop in engagement within a week. This confusion affects customer retention and reduces conversions."

Watch as UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains important points about design thinking:

You've probably all had some problem you've worked at. And you keep going at it, and you keep going at it... Nothing seems to work. You go away. Suddenly, the next day you think, 'What problem? It's easy!' It's something I said I've certainly had, and I'm sure you've encountered. And psychologists and other people studying creativity have looked at these kind of issues – why it is that we get to these impasses and how it is that we break out of them.

*Fixation* is one of the keywords that psychologists use here: the way in which when you start to deal with a problem, you have some sort of approach, some sort of way of dealing with it, and it's incredibly hard to stop just continuing with that same way. Once you've got that original idea, that original approach, it's very hard to go to a new one. And sometimes – you know – an approach that might work for one problem doesn't work for

another, but of course if you're stuck in that approach, you can't try other ones. This can get worse depending on how you encounter the problem. And this is sometimes used in sort of trick questions to get you thinking down the wrong track and then it's very hard to get down the right one. And this is sometimes called – if I can say it right! – the *Einstellung effect* which is about being fixed in a position.

These guys called Luchins and Luchins back – I think – in the 1940s did experiments with water jars. And you've probably seen this sort of puzzle. You've got a number of jars, and the idea is they're different sizes and you're trying to get, say... two pints of water and you've got a 17-pint jug and a 3-pint jug and you've got to pour water back and forth. And there sometimes are really complicated solutions where you have to like fill one up from another, and then what's left in this one is some nice magic amount.

So, if you've got a 3-liter jug and a 7-liter jug and you fill the 7-liter one and you pour it into the 3-liter jug and then throw the three liters away, you've got four liters in your 7-liter jug. And you have these complex solutions. So, what Luchins and Luchins did was they gave people a number of examples which they worked through which required that kind of complex solution. And then they gave them four more. But the four more they gave them were ones where you could actually solve it very, very simply. You know – possibly just filling up two and pouring them into another.

So, some subjects were given that; some were just given the four easy problems. The ones who were just given the four easy problems solved it in the easy way. The ones who *started off with the complex ones applied the same complex heuristics* to the easier problems and took *much longer* to do it. So, they got so stuck in their ways having been introduced to this set of problems. One that I encountered myself, and this gives you an opportunity to laugh at me if you want to,

because you'll probably, most of you I'm guessing might find this easy, but I was in university and I was once given this puzzle. And the puzzle starts off – and there is this stage where you're driven down the wrong path – anyway, so I'm giving you a hint by telling you that. So, you often get these puzzles where you're supposed to chop things up into identical pieces. So, I've got a square up there, and obviously you can chop a square into four identical

smaller squares. Or you can chop it into four triangles. So, the triangles are all the same shape as each other, the same size as each other. In mathematical terms, they are *congruent to* each other. But they're not necessarily squares. I've got some triangles, and we can chop the triangles into four; they're different kinds of triangles in different ways. And on the right I've got one of the ones you sometimes see as a trick puzzle in books; and – or sometimes actually cut out pieces as a sort of trivia-type puzzle.

And the idea there is to have four pieces that will make up that 'L' shape. And certainly there may be other ways of doing it, but the way I've always seen is with these four pieces like that. So, they're all 'L' shapes themselves and they fit together. How about cutting things into three? Well, obviously, the 'L' shape is an easy one, and things that start off with three degrees of similarity like a triangle or hexagon are relatively straightforward.

So, the crucial question is, can you chop a square into three pieces that are congruent with one another? Not all squares, but some shape – they could be triangular; they could be more complex – that are each identical. Can you do it? Now, my guess is you've probably already thought of how to do it and you'll be right. It took me three days to solve this because I was a mathematician and the whole thing was framed in geometry, mathematics,

and I was trying to apply really complex mathematics. And despite numerous hints, it took me three days to solve this. If you haven't solved it, you're probably a budding mathematician. So, *fixation is a problem*. There's also – fixation is more about the methods you use to apply things, but there's also *bias* – when you *evaluate* things. When we look at them, we have tendencies to see things in one way or another. And that's about all sorts of things.

That can be about serious personal issues. It can be about trivial things. Often, the way in which something is *framed* to us can actually create a *bias* as well. A classic example, and there are various ways you can do this, is what's called *anchoring*. So... if we're asked something and given something that *suggests a value* even if it's told that it's just there for guesswork purposes or something,

it tends to hold us and move where we see our estimate. So, you ask somebody, 'How high is the Eiffel Tower?' You might have a vague idea that it's big, but you probably don't know exactly how high. You might ask one set of people and give them a scale and say, 'Put it on this scale. Just draw a cross where you think on this scale, from 250 meters high to 2,500 meters high, how high on that scale? And people put crosses on the scale – you can see where they were, or put a number.

But alternatively, you might give people, instead of having a scale of 250 meters to 2,500 meters, you might give them a scale between 50 meters and 500 meters. Now, actually the Eiffel Tower falls on both of those scales: the actual height's around 300 meters. But what you find is people don't know the answer; given the larger, higher scale, they will tend to put something that is larger and higher even though they're told it's just a scale.

And, actually, on the larger scale it should be right at the bottom. Here it should be about two thirds of the way up the scale. But what happens is – by framing it with big numbers, people tend to guess a bigger number. If you frame it with smaller numbers, people guess a smaller number. *They're anchored by the nature of the way the question is posed.* So, how might you get away from some of this fixation? We'll talk about some other things later, other ways later. But one of the ways to actually break some of these biases and fixations is to

*deliberately mix things up*. So, what you might do is, say you're given the problem of building the Eiffel Tower. And the Eiffel Tower I said is about 300 meters tall, so about a thousand feet tall. So, you might think, 'Oh crumbs! How are we going to build this?' So, one thing you might do is say, 'Imagine, instead of being 300 meters tall, it was just *three* meters tall. How would I go about building it, then?' And you might think, 'Well, I'd build a big, perhaps a scaffolding or 30 meters tall.

I might build a scaffolding and just hoist things up to the top.' So, then you say, 'Well, OK, can I build a scaffolding at 300 meters? Does that make sense?' Alternatively, you might, say, perhaps it's *300,000 miles tall* – basically reaching as high as the Moon. How might you build that now? Well, there's no way you're going to hoist things up a scaffold – all the workers at the top would have no oxygen because they'd be above the atmosphere. So, you might then think about hoisting it up from the bottom, building it,

building the top first, hoisting the whole thing up, building the next layer, hoisting the whole thing up, building the next layer. You know... like jacking a car and then sticking bits underneath. So, *by just thinking of a completely different scale*, you start to think of *different kinds* of *solutions*. It forces you out of that fixation. You might *just swap things around*. I mean, this works quite well if you're worried about – that you're using some sort of racial or gender bias;

you just swap the genders of the people involved in a story or swap their ethnic background, and often the way you look at the story differently might tell you something about some of the biases you bring to it. In politics, if you hear a statement from a politician and you either react positively or negatively to it, it might be worth just thinking what you'd imagine if that statement came to the mouth of another politician that was of different persuasion; how would you read it then? And it's not that you change your views drastically by doing this, but it helps you to

perhaps expose why you view these things differently, and some of that might be valid reasons; sometimes you might think, 'Actually, I need to rethink some of the ways I'm working.'

To find the real problem, you’ll want to start by observing users and listening to feedback. Then, watch how they interact with the product and ask open-ended questions about their experience.

Use the “5 Whys” technique to dig deeper—a major source of help to drill down beneath apparent causes to the real deals that lurk behind. If users abandon checkout, then ask them why. If they say it’s confusing, ask what part—keep on going until you reach the root cause.

Look at data and patterns: high drop-off rates, low engagement, or repeated support tickets often point to deeper issues. And be sure to talk to customers, support teams, and stakeholders—each group will see the problem from a different angle, a point that you can leverage to get behind each pair of eyes. For instance, a business might see low sales, while users struggle with a complicated form.

Remember to stay in the problem space and explore it without jumping to solutions too early. Focus on what’s wrong, not how to fix it. It may be difficult to resist the urge, but keep your eyes on—or “peeled” for—a real problem that affects users, business goals, or both. Research, ask questions, and analyze data before writing a clear and focused problem statement. When you get the full picture in sharp relief, you’ll feel relieved that you held on until you found the true cause of the real problem rather than chasing a shadow into a dark zone where you might end up building the wrong thing.

Watch as UX Pioneer Don Norman explains important points about the 5 Whys method:

I've talked about the need to find the root cause of a problem and not just to solve the symptoms. It's important, by the way, to solve the symptom – you don't want that to stay around. But we also need to get rid of the *underlying cause*. Or else it'll come back again; the symptoms will repeat. So, how do you do that? Well, the Japanese developed a technique on, actually, the Toyota assembly lines.

They call it the *5 whys*. Now, the 5 whys sounds good, and you can do that yourself – you can always say "Why?"; when somebody tells you something, you say, "Well, why is that?" And they'll tell you why that is, and you know you've sort of reached the root cause when they say, "I don't know." because actually you can *never* really get at the *very, very bottom*. So, what we need to do is get at the *lowest level* that we can actually *do* something about. In the United States – and probably in every country –

when there's a major airplane crash, when they issue their report, which is often a year or two after the event, they don't say, "This was caused by pilot error." or, "This was caused by a faulty altimeter." or, "This was caused by a bump." What they usually do is they say, "There were *many* things happening, and here's a list of things. And if any one of these had not happened, there would not have been an accident."

So, if there are – say – eight things that led to the accident, any one of which could have prevented the accident, how do you know which is the *root cause*? *All eight* are the root cause. So, you have to therefore look at the *whole system* and find out what the *entire underlying set of possible root causes* is and work on them.

To validate a problem statement, talk to users and stakeholders to confirm if the issue is real and important. Start by asking open-ended questions—and let users describe their challenges in their own words. If their feedback matches your statement, you’re on the right track.

Use surveys, interviews, or usability tests to get the insights you want. Look for patterns in complaints or struggles; if multiple users mention the same issue, it likely needs attention.

Share the problem statement with stakeholders—team members, managers, or clients—and ask if it aligns with business goals and real user needs.

Check data to support your findings. High drop-off rates, low engagement, or repeated support tickets often confirm a problem and data-driven design is the sort of design that, via the power of such foundations as quantitative research, will act as the fulcrum over which you can lever your eventual design solution to the best possible effect and turn on your users—and so, minimize the risk of their turning on your brand after they dislike design missteps you might make otherwise.

In a similar vein, stay away from confirmation bias—don’t lead users toward agreeing; let them respond in earnest, and it will help to let their feedback shape the statement.

Watch as UX Strategist and Consultant William Hudson explains why Data-Driven Design works—and can work well for you:

The big question – *why design with data?* There are a number of benefits, though, to quantitative methods. We can get a better understanding of our design issues because it's a different way of looking at the issues. So, different perspectives often lead to better understanding. If you're working in project teams or within organizations who really don't have

a good understanding of *qualitative methods*, being able to supplement those with quantitative research is very important. You might be in a big organization that's very technology-focused. You might just be in a little team that's technology-focused, or you might just be working with a developer who just doesn't get qualitative research. So, in all of these cases, big, small and in between, having different tools in your bag is going to be really, really important. We can get greater confidence in our design decisions.

Overall, that means that we are making much more *persuasive justifications* for design choices.

Yes, a problem statement helps in competitive analysis by showing where competitors fail and where opportunities exist. It defines what users struggle with and helps compare how competitors handle the same issue.

Start by analyzing competitors’ products, and then go on and look at reviews, complaints, and user feedback to see if they face similar problems. For instance, if users mention slow checkout on a competitor’s site, compare it to your own process.

Use the problem statement to find gaps in the market—you might be surprised at what turns up. If competitors offer complex solutions, simplify yours; if they lack key features, consider adding them. The possibilities may not be endless, but there can be a good number of ones you can “milk” to great effect.

Another thing is that a clear problem statement also helps position your product—and that’s because it guides decisions on pricing, messaging, and features to stand out. Above all, a problem statement is rather like a compass—in that it gives you direction on how to solve real-world user problems better. Think of it like sailing in a regatta where competitors are the other “vessels.” Although they might have a good idea of the general direction and what they need to do to get there—and win!—they might lack the “compass” of a problem statement. And that means that if you can use a problem statement (or POV) to guide you—and not just follow their path (i.e. trends) and copy what they’re doing—you can end up “winning the race,” or, that is, solving real users problems best.

Watch as UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains important points about competitive research:

OK, here's a scenario: You're a designer on a product that connects job hunters with great new careers. Your team is currently working on a new screen that will let applicants search by categories. Your job is to figure out what the categories should be. Well, obviously the easiest way to figure this out is with some research. There are a bunch of different sorts of research that you could do; you could do *quantitative*, for example; you could do some *analysis* maybe of the search terms that people are already typing in

and see if there are any obvious categories; you could also do some *competitive research*, maybe check out some other sites and see if there are any common terms; or, of course, you could do the gold standard and actually *observe some users searching for jobs*. But here's the problem: Those all *take time*. And the engineer who was assigned to the user story wants the answer from you so that they can finish before the end of the *sprint*, which is on Friday. But you were just designing a story; how are *you* supposed to solve this problem?

It turns out this happens quite a lot on agile teams and it can be *extremely frustrating*. The thing is, this is indicative of a very common anti-pattern often called "feeding the beast". In this instance – in *all* instances – the engineers are the beast. There are a few ways to handle this. The first requires that stories be treated differently. Researchers and designers could work on their stories *ahead* of engineering, and by the time engineering gets them, the acceptance criteria are all set. In other words, you'd get this story a few weeks early, get to go do your various forms of research,

come up with a good solution, and then the story would go to the engineers. That's fine. And it's what happens on a lot of teams who are what we call "agile-ish". But it's not particularly cross-functional or collaborative. Another way of approaching it is to actually involve the engineer you're working with on making the decisions. For example, maybe they can help do some data analysis on the search terms while you do some competitive analysis on the competitors' types. You could both work together to observe some real users. Meanwhile, the engineer could do a bit of exploration to see if there are any technical reasons why certain types of categories would be

easier or harder to implement than others. You would be shocked at how often there are weird technical constraints that you do not find out about until an engineer sees a story, which means it's really much better to get them involved as soon as possible. Of course, this may mean it takes you a little bit longer than a single sprint to get the whole story done; although, again, that can depend on how fast you are or how big the feature is or how long your sprints are. On the upside, you know that any design will be technically feasible because you're involving the engineering team in the decision-making process.

You also know that the engineer implementing the story actually understands the user needs and goals. Depending on the design, it may drastically reduce the number of deliverables you need to create. I mean, if you've already done co-design exercises and sketched out ideas with somebody, you often don't also need a designer to create pixel-perfect mockups to show them exactly how something works. Will this kind of group research work in every single instance? No; sadly not. It depends on a lot of things, not least the willingness of the engineers to be involved in the research.

On some teams, engineers could get penalized if they spent too much time on a story. So, this sort of research would end up being bad for their careers. This is incredibly unfortunate, and if your team is like this, it's honestly worth trying to get it changed because the benefits of doing research together strongly outweigh the slight negatives of maybe moving a bit slower in some cases. In fact, often doing research and design like this can end up making a team move faster in the long run simply because there's less miscommunication among team members and less need for complex deliverables to be passed around.

Of course, doing research together doesn't necessarily mean that everybody on a team does all research all together all the time; you're still doing larger, more open-ended studies that take a longer time. And if you've got one researcher and designer and several engineers and a product manager, you're not all going to go to all of the sessions together – that would be a little overwhelming. But be sure to *include* various members of the engineering and product teams and even marketing or sales or customer service or anybody else who has an impact on product decisions *when you're doing your research*. Not everybody will go to every research session, but having people on your team

watch your customer experience first-hand can really help your team be much more agile by giving everybody the context that they need to make better decisions about whatever they're working on. Of course, this does tend to work best with smaller teams, but then that's true whenever you're using agile methodologies. They're all designed around this idea of a truly cross-functional, collaborative, reasonably sized product team that is at least partially autonomous and can make actual decisions about what to build and how to self-organize.

If that doesn't describe your team, team research is going to be harder; although it's still not impossible, it just takes some work.

Ellis, T. J., & Levy, Y. (2008). Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem. Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline, 11, 17–33.

This paper provides a comprehensive framework to assist novice researchers in developing research-worthy problem statements. It emphasizes the centrality of a well-structured problem statement in guiding quality research and offers practical guidelines for its formulation.

Annamalai, N., Kamaruddin, S., & Azid, I. A. (2013). Importance of Problem Statement in Solving Industry Problems. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 421, 857–863.

This study discusses the role of problem statements in industrial problem-solving contexts. It highlights how a well-defined problem statement—encompassing scope, structure, and purpose—is crucial for effective analysis and the development of solution strategies in industrial environments.

Garrett, J. J. (2011). The Elements of User Experience: User-centered design for the web and beyond (2nd ed.). New Riders.

Jesse James Garrett provides a comprehensive framework for understanding all aspects of user experience design. The book emphasizes the importance of defining clear problem statements to guide the design process, and so to ensures that solutions are aligned with user needs and business goals.

Kolko, J. (2014). Well-designed: How to use empathy to create products people love. Harvard Business Review Press.

In this book, Jon Kolko emphasizes the role of empathy in design thinking. He discusses how understanding user emotions and behaviors leads to the formulation of insightful problem statements, which guide the creation of meaningful and engaging user experiences.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Problem Statements by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

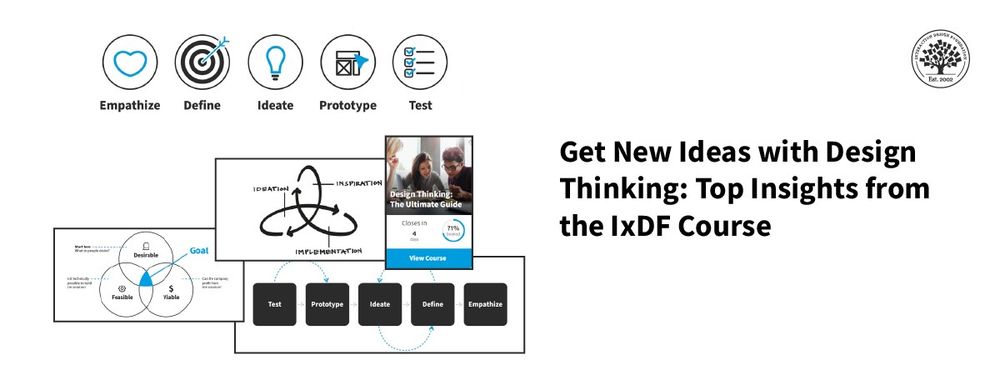

Take a deep dive into Problem Statements with our course Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide .

Some of the world’s leading brands, such as Apple, Google, Samsung, and General Electric, have rapidly adopted the design thinking approach, and design thinking is being taught at leading universities around the world, including Stanford d.school, Harvard, and MIT. What is design thinking, and why is it so popular and effective?

Design Thinking is not exclusive to designers—all great innovators in literature, art, music, science, engineering and business have practiced it. So, why call it Design Thinking? Well, that’s because design work processes help us systematically extract, teach, learn and apply human-centered techniques to solve problems in a creative and innovative way—in our designs, businesses, countries and lives. And that’s what makes it so special.

The overall goal of this design thinking course is to help you design better products, services, processes, strategies, spaces, architecture, and experiences. Design thinking helps you and your team develop practical and innovative solutions for your problems. It is a human-focused, prototype-driven, innovative design process. Through this course, you will develop a solid understanding of the fundamental phases and methods in design thinking, and you will learn how to implement your newfound knowledge in your professional work life. We will give you lots of examples; we will go into case studies, videos, and other useful material, all of which will help you dive further into design thinking. In fact, this course also includes exclusive video content that we've produced in partnership with design leaders like Alan Dix, William Hudson and Frank Spillers!

This course contains a series of practical exercises that build on one another to create a complete design thinking project. The exercises are optional, but you’ll get invaluable hands-on experience with the methods you encounter in this course if you complete them, because they will teach you to take your first steps as a design thinking practitioner. What’s equally important is you can use your work as a case study for your portfolio to showcase your abilities to future employers! A portfolio is essential if you want to step into or move ahead in a career in the world of human-centered design.

Design thinking methods and strategies belong at every level of the design process. However, design thinking is not an exclusive property of designers—all great innovators in literature, art, music, science, engineering, and business have practiced it. What’s special about design thinking is that designers and designers’ work processes can help us systematically extract, teach, learn, and apply these human-centered techniques in solving problems in a creative and innovative way—in our designs, in our businesses, in our countries, and in our lives.

That means that design thinking is not only for designers but also for creative employees, freelancers, and business leaders. It’s for anyone who seeks to infuse an approach to innovation that is powerful, effective and broadly accessible, one that can be integrated into every level of an organization, product, or service so as to drive new alternatives for businesses and society.

You earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you complete the course. You can highlight them on your resume, CV, LinkedIn profile or your website.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!