The Pareto Principle and Your User Experience Work

- 785 shares

- 5 years ago

UX (user experience) project management combines traditional project management techniques with UX design principles so design teams can create digital products that meet and exceed user expectations. UX project managers oversee the process of improving user experience across digital platforms, like websites, apps or other applications that need user interaction.

Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains important points about creativity including in project management design:

I'm going to talk now about plans, as in sort of largish-scale plans over weeks perhaps, perhaps months, for creativity. Say, for creativity, for innovation – the words have slightly different meaning, but for things where you need a creative step, but not necessarily – I'm not thinking Einstein here; I'm thinking more the kinds of creative step you need

in your day-to-day user experience, software development, whatever particular aspect you're in, you're after. Crucially, innovation is often attached to risk and creativity is attached to risk. And typically, when people say 'risk', they're thinking high gain but also a possibility of failure. And that's fine – apart from sometimes you can't afford to fail.

So, what you really want, ideally, are *high-gain, but low-risk activities*; so, things where you're guaranteed to get something but you might get something really good. And that's what I'd like to talk about – ways to achieve that. So... high risks or innovative strategies seem to be risk of failure, conservative ones low-risk but not very exciting.

Can we get the best of both worlds? The typical way, when you think about plans – if you're going to go and you write your Gantt chart or whatever, you think of them as not necessarily linear; you might have parallel activities, but lots of small steps where you're saying 'I'm going to do this on these days; these on these days; this person's doing this; this person's doing that.' All pre-planned, guaranteed outcome – you know that you can achieve each of the steps. You know that you do each of the steps, you get to the end and you've got your result.

Brilliant! But maybe a little boring. So, again, can we do something a bit better than that? Well, of course, there is a creative plan. So, a classic – and this is both something you might informally do, but also I have seen formally written plans like this, which you can think of as the 'spark from heaven' plan. So, you have a series of activities that perhaps happen up front. And then, your plan,

I said you might not write it down, but your plan is basically that you *wait for the spark of creativity*. There's the big bright idea; once you've got your bright idea, you move on. So, I've seen things like research or development plans that say, 'First of all, we're going to review what's there. And then, we'll invent the new method, the new toolkit, the new way of doing something. 'Spark from heaven' plans: brilliant when they work, disaster when they don't.

So, this is a classic high-risk plan. So, how can you modify this kind of bigger bright idea plan to make some things more likely to succeed while still having the opportunity to produce really good things? One kind of plan that works quite well, I found, are *incremental output plans*. Now, this works, perhaps – well, we'll talk about some examples actually later.

If you're writing, it might be about writing things that come in units so that you can deliver things. If you're producing software, it might be producing something minimal and then additional parts. But the basic idea is you have a linear plan – or it doesn't have to be linear; it can be a branch, but think of a linear plan, *with multiple stages*, where each stage might require little sparks inside, but smaller sparks;

so, smaller sparks spread out; but then crucially at each stage, so you've got those high-risk elements; I said normally they're dangerous, but because you've broken them up, the likelihood is that one of them will happen. And this can be highly linearized, so you have to have the first one first. But if it's smaller bright ideas, you're more likely to have it. Or it might be actually you could do things in different orders and be a bit more speculative about which order you do things.

But crucially, each stage, when you have the spark of insight related to that stage, has a related output. And so, at every point from the first stage or two, you actually have something that you could *deliver*. Now... from an overall management point of view, from a project management point of view, knowing you've *got something*, even if it's not what you'd really like, is *brilliant*. So, and it's particularly good if you've got a limited time, so there are different kinds of constraints

in time. Sometimes it's the amount of time you've got to spend on it in total, but often there's a *hard deadline*. If there's a hard deadline, if you have to deliver something by that deadline, then actually a plan that's guaranteed to give *something*, even if it's not the most wonderful thing at that deadline, is a good plan. The more of the stages you go through, the better the plan you have. And if you fail on the last one, so what?

You've missed a little bit, but you've still got something pretty good. Examples of that – in Agile development methods, I'm sure a lot of you have worked with Agile development teams. You're often based around a user story or a scenario-based one where you take a particular user story and say, 'We're going to, this week, this fortnight (2 weeks), this month,' – depending on how long you do your sprints over – 'we're going to implement this slice of functionality.' You implement that one; then you move on to a different one.

You need to have a level of innovation, a level of – I mean, this is true both from the development point of view, from the user experience design point of view. You need your sparks for those (inaudible). But each one is a relatively contained thing that you can finish. The other thing is that if you have, shall we say, a 'palette' of them, what you might do is during... your weekly review meetings about where you're at,

you might actually choose to do the story where you've got a pretty good idea of what you're going to do. So, effectively use the sparks to drive the order in which you do the stories. So, you have a number of stories that you want to implement. They're part of what you'd like to do; you do those. Now, this is related to the whole idea of a *minimum viable product*. So, is there something you can produce that you can get out there that does the job? And then you've got a roadmap (inaud.) wish list, that you might do in a particular order, and then it's a matter of waiting to do those creative steps for each one.

Or it might be that if you've got a road map, a wish list of things to do, when you sort of realize 'Ah! That's how we can do that one!' you get on and do that one rather than the rest. So, it's like having a *menu* of things that require *creative steps*, but each one of which when you do them, you can add to that minimum viable product, make it a more extensive one, something that's more appealing. A similar – well, it's similar in the sense that it reduces risk, although actually very different –

is what you think of as a *back burner activity plan*. So, the idea here is you have your classic 'spark from heaven' plan where you've got something and you're waiting for the big idea. But what you do is, in addition, you have a *parallel activity* that you can get on with. Now, *sometimes that's related but not the same*. So, imagine you've got actually an application idea of your own you're trying to develop, and you think it's going to be great, but it takes time

and you certainly need a certain amount of insight to hit your head. So, what you do is you're doing consultancy work; it's in the just same general area. So, it helps *feed your brain with ideas*, but pays for your bread and butter – allows you to live and to pay your rent and everything while you develop your new bright idea; so, that might be it. Or it might be a *low-risk path to the same outcome*. So, you have a project you have to do.

And you'll think – again, we'll go back to the to-do list application; so, you have to develop a to-do list app. You know you've got to do it. You know what to-do lists look like – applications. There's a gazillion to-do list apps; so, you could just do yet another to-do list app. So, what you do is you *get on with doing that*, but at the same time you're *thinking about novel and different ways to do it*. Because you're doing something related, it's feeding in. So, as you get on with the bread and butter

to-do list app that's sort of just doing its job but in a fairly boring way, it's keeping your mind thinking about to-do list apps. And if – and hopefully if, that will, one is, make it more likely and then if the sudden 'Ah yes!' idea comes, you then effectively shift into doing the more creative but high-risk activity. It's quite nice too if the steps that you're doing in the high-risk activity can

feed back into the low-risk one. So, you might – I mean, that's less true if there's like one huge big idea, but the low-risk activity might itself be a bit more like the incremental would have a series of things and you might perhaps having done one of them, be able to feed some of those ideas back into your more day-to-day mundane plan for producing the to-do list application. So, the idea is to have something that you just know you can get on with, will produce a result;

you know – that result might be earning your money so you could live; it might be producing the application at the end, but something else in parallel which sort of sits there and is it what you really want to do? And when the ideas come for it, you get on with it. Okay, that's a *back burner activity*. The other thing you can do, which is sort of essential for the incremental one but is a general strategy, and it's sort of blatantly obvious, this, is

take that one big idea – can you break it down? Can you think of things that are smaller, but when you've done them all, either means that you've done the big activity or sometimes are just preparatory, but each one of them is of value in itself, and often the last small idea you need is how to pull them all back together to bring them back into the big idea? So, ways of breaking things down:

So, you can think about activities. I mean, there are multiple dimensions, and I'm going to push it down to two because otherwise you can't see it on a slide. Let's think about the things that you're doing in terms of two axes. One is in terms of *complexity*. How complex? Is something really simple or is something a really complicated thing? And in terms of the *amount of creative energy required*.

How creative do you need to be to do the task? Now, there are some things that are both really simple in terms of complexity and don't require a lot of creativity. So, I can go out and make a cup of tea for myself anytime. You know – that's low creativity, a low-complexity task to do. If you've got a load of those to do, one – I mean, sometimes they can be a useful back burner activity, but one thing particularly often I find myself trying to do is clear the decks of those

because they can take over your life. In the pebbles and boulders model, they're the *pebbles*. So, one is they can take over and there's too many of them. But often, the fact that they're sitting there on your head, you know you've got to do these little tasks. I often find if you can, spend a bit of time, get them out of the way – that's useful. So, there's *strategy* – so, again, you might have different strategies, but they have a particular strategy for dealing with them. Or you might say, 'I'm going to schedule a day a week for doing these,

or an hour in the morning for doing those tasks. That's it.' I mean, I prefer to produce biggest possible ones; so, I might go for the day a week. But I said it does depend on your schedule, where you work, how it's going to do. The other kind of thing, you might have *things which don't require much creativity but are quite complicated*. Now, I mean that's weird because – but things can be biggish and yet you just know that if you get on with them, they'll happen. For those, if you're wanting to do something creative, two things you can do with those:

One is you can *deliberately schedule them for later*, so you can move them off into the future. I sometimes talk about *Micawber management*. The use of procrastination, but as a positive thing. And this is an example of Micawber management. You're saying, 'I know I've got this; there's this complicated thing. It's going to take a lot of effort. What I might want to do is just say, "But I know because it's not going to require huge

amounts of creative insight, that this will take me a day, a week, an hour; where's its deadline? When do I need to do it?"' ... pushed off; so, into the future. The other thing you might do with these is use them in that back burner model as the parallel filler activity; so, the thing to do whilst you're waiting for the big idea, basically. The thing you have to be a little bit careful with these, using that is

if they're *complicated but are taking mental energy*, then they get in the way of the creative thought. However, that by very definition pushes them up into the bigger emotional or creative energy tasks. So, if they're low creative energy, if they're things you can just get on with but are quite complex, then you might do them as your back burner activity whilst you're doing the things that you have to sort of perhaps wait for that moment when it's 'Ah – yeah! That's right! Get on with it.' Okay, let's look at the top left of this thing now. So, things which are

*low complexity but require a substantial amount of creativity*. So, these are little puzzles – you know. It might be as simple as 'What name should I give for this menu item?' – you know; it's that kind of thing, or... but they're things that – you know – you do have to think about, do require a bit of processing; so, they're eating up your creative thinking, but they're relatively small. These are often little fun tasks, actually, because you know you're going to get them done;

you know they're not such a huge thing that you think, 'Oh my goodness! Will I ever think of that many (inaud.)?' – you know. You know you're going to do it; you might have some strategies for helping you doing it. There is a category of things up here, though, that are *not fun*. And... You know – you'll have different ones, but I'm rubbish at like sending – certain emails. Some emails are fine, but there are ones where I'm just worried about how to *phrase it*;

so, it's not so much creative energy as *emotional energy*. And what I will do is I can spend a day not doing that task. So, for those things, these things which are more problematic, again you either want to try and clear the decks of them, so I'm going to push it down to the bottom. Or, even though it's quite small, put it off, schedule it so that it's not forgotten – you know it's not forgotten, and it may, but hopefully by scheduling it into the future, it makes it less of a weight on your mind. Okay, now the *gap* – the yawning void here on this diagram is the things that

*require creativity but are also complex*. There, I said we're not talking about complex in the Einstein general relativity sense, but in the new idea of how you're going to organize this new application in some way that's going to be different from your competitors and yet it's going to be easy to use; it's going to be immediately attractive when they first see it, and it's going to continue to enthrall them for weeks and years to come – you know.

So, this is non-trivial stuff. You know – this is the Nirvana up here; this is it, right? But it's hard – these are the *hard things*. What good planning should do is help you to break that down into things that either actually require *no creativity at all*, or are these *lower grade things*, these things that require those creative insights but are more fragmented.

UX project managers have a diverse set of responsibilities—and these span various aspects of the product development and service development lifecycle that are involved in the overall project, where managers:

Project managers manage the user experience of digital products and focus on user engagement and interaction as well as user and customer satisfaction.

Project managers harness the skills of user interface (UI) and UX designers, creative teams and marketing departments to carry out work on everything from the planning phase, research, ideation of potential solutions and iterations of these. They also take project execution in hand and spearhead digital campaigns, plus keep efforts optimal regarding project deliverables to complete the project and achieve maximum success beyond launch.

Project managers create strategies to combine the skills of all disciplines that go into creating a user experience. UX project managers make sure to make the best strategies so that design objectives align with business goals and user needs throughout the project lifecycle.

A typical approach to project management is to lead user research and analysis efforts—which include interviews, surveys and usability testing—and it’s a crucial part of a manager’s role.

UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains important points about user research:

Managers use effective project management methodologies—like Waterfall or Agile methods—to guide their teams’ project.

UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains important points about Agile design:

It’s vital that managers keep open communication channels going with the whole team and stakeholders. They need to facilitate excellent, real-time collaboration between various creative professionals and bridge the gap between designer and developer communications.

Laura Klein explains important points about cross-functional collaboration:

UX project managers oversee resource allocation, task delegation and goal setting. They define realistic roadmaps and the project timelines it needs. What’s more, they assign tasks to the right team members.

A project management foundation is for managers to implement corrective actions with contingencies when things don't go according to plan and manage project risks effectively.

As managers oversee the entire process, they help maintain the quality of the final product from their heightened perspective. They make sure that a brand’s web design, for example, really is enjoyable, interactive and user-friendly.

One point to highlight in particular is how management here is the crucial overarching force behind brands that create digital products that don’t just meet technical requirements but provide the best possible user experience, too. However, UX project manager jobs are hands-on, as the role calls for a proactive force to lead from the front and help gel the various teams and stakeholders together. It’s a job description that combines the analytical aspects of project management with the creative elements of UX design, so that the products—or services—that a design team, development team and other departments involved have to show for their efforts are both functional and user-friendly.

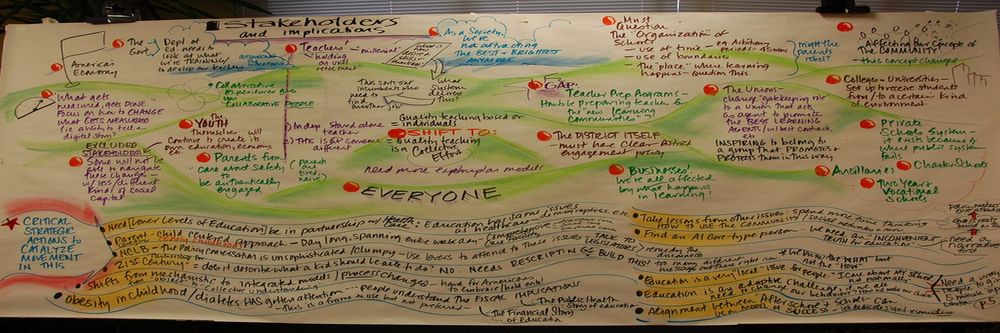

This example is of a product manager’s work process—one form of project management.

© User Experience, Fair Use

UX project managers need a diverse set of skills to excel in their roles. These skills broadly fall into the categories of technical skills and soft skills—both of which are crucial for success, whether traditional approaches or an Agile approach are involved, for instance.

UX project managers must possess a range of technical skills if they’re to effectively lead projects and teams. It’s a key point that means UX designers who are proficient in their work have a head-start if they want to transition to become UX project managers—and here are main areas:

It’s vital for managers to have a solid understanding of visual design principles—including color theory, typography and layout. Their proficiency in the principles as well as design software is a fundamental part of what allows UX project managers to create and evaluate visual elements of a product.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

How able a manager is to plan, conduct and analyze findings from various research methods is critical. This includes user testing and analytical research to understand user needs and behaviors.

UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains key points about analytics:

Another vital area for UX project managers to be adept in is to organize information in an understandable way. This skill applies to websites, apps software—and even physical spaces—and involves systems like labeling, navigation and search functions.

William Hudson explains important points about information architecture:

It’s a fundamental skill for managers to be able to create wireframes and prototypes. Wireframes serve as blueprints for interfaces—the early foundations on which to build strong ideas and shape effective architectures.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Meanwhile, prototypes let teams test functionality before their efforts channel into final product development.

Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains essential information about UX prototyping:

A deep and solid understanding of Agile project management practices is valuable for managers to have. That’s because many software development teams use this iterative approach. Project managers often head up Agile teams.

While UX project managers aren't expected to code, a basic understanding of languages like JavaScript, CSS and HTML can be beneficial when they’re communicating with developers.

Co-founder of Hype4, Szymon Adamiak explains ways to communicate better with developers:

Alongside their technical skills, UX project managers need to cultivate a strong set of soft skills so they can lead teams effectively and make sure project success is on point for the brand and its target users:

Strong communication skills are essential ingredients for managers to know what goes into doing user research, presenting designs to stakeholders and collaborating with team members.

Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach, Todd Zaki Warfel explains important aspects of how to communicate with stakeholders and clients:

UX project managers frequently work with various teams and personnel. These include leadership, UI designers and developers. So, they need to be able to collaborate effectively as they help direct things to keep everyone on point for project success.

As project leaders, UX project managers need to guide their teams, make decisions and take responsibility for project outcomes.

Managers need to stay aware of and be proactive about who’s handling what.

© Julia Martins, Fair Use

Managers often have to think on their feet as they move between teams—the ability to analyze complex situations, identify issues and develop creative solutions is vital in UX project management.

Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains vital points about the Six Thinking Hats approach, a handy tool to solve problems with for managers and others:

UX projects can experience many twists and turns as realities unfold—over everything from budget to team issues. So, managers need to be flexible and able to adjust to changing project requirements or unexpected challenges.

To manage multiple projects or aspects of one project demands excellent time management and organizational skills.

With so many team members and others involved in a project, personalities and preferences might well come into conflict sooner or later. So, it’s vital that an effective project manager be able to navigate and resolve conflicts, be it within teams or with stakeholders.

As leaders who represent the brand at the design and development levels, UX project managers need to have a deep understanding of those essential ingredients that design solutions need to do well in the marketplace—including the legal ones. For example, that’s why accessibility is so important for project managers to ensure becomes part of each design project.

Watch our video to understand more about accessible design and why it’s crucial:

UX project managers use various frameworks to guide their work and make sure their teams and brands can enjoy successful outcomes with what they produce for their target audience. Three popular frameworks in UX project management are Agile, Waterfall and Lean UX. Each framework has its unique approach in how to manage projects and deliver truly user-centered designs.

Agile UX combines Agile software development with UX practices. This framework places UX specialists within Agile software teams and creates a culture that values the UX process. Agile emphasizes individuals and interactions over processes and tools—something that lets teams respond flexibly to business needs.

Key features of Agile UX include:

Teams carry out UX work ahead of development sprints.

UX specialists analyze short- and long-term solutions.

UX specialists lead activities to nurture good collaboration.

Established processes keep a tight focus on user-centered design.

Common Agile frameworks include Scrum and Kanban.

UX Designer and Author of Build Better Products and UX for Lean Startups, Laura Klein explains essential points about Kanban boards:

The Waterfall methodology is a linear project management approach that software developers more or less “inherited” from the construction and manufacturing industries. In this framework, managers split project tasks into phases that follow a sequential order—much like a waterfall—where teams complete sections of work and then pass it on.

A typical Waterfall process consists of five to seven phases:

Requirements gathering

Design (logical and physical)

Implementation

Verification

Maintenance

The Waterfall approach is adaptable to incorporate UX activities within the project lifecycle. UX managers can see that designers conduct user research, create information architecture and perform usability testing at various stages of the process.

Waterfall works best for smaller projects with fixed budgets, release dates and scopes. It's suitable for applications that don't need frequent updates, too.

Lean UX’s focus is on the experience that’s under design and not so much the deliverables themselves. Lean’s core objective is to collect feedback as early as possible so the insights can come to help with quick decision-making.

Lean UX principles include to:

Implement a design system or component library.

Decouple front-end and back-end code.

Establish a user research practice.

Use OKRs (Objectives and Key Results).

Lean UX works well in Agile development environments, where teams execute work in rapid, iterative cycles. This approach lets teams plug the data they’ve generated into each iteration so they can use it most effectively.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Each of these frameworks offers unique advantages for UX project management. The choice of framework depends on the project's specific needs, team structure and organizational culture, so UX project managers need to understand such frameworks if they’re to pick the most appropriate approach for their projects and adapt them as they need to make sure the best outcomes happen.

Effective UX project management relies on a combination of tools that enable collaboration, design, prototyping, user testing and higher aspects of management. The most important tools split into two main areas, to help across various stages of UX projects:

Project management tools help make a blueprint and keep everyone on the same page with a big-picture view. Several popular project management tools help design leads manage big projects with multiple team members and stakeholders effectively. For example, Gantt charts can be extremely helpful. Without such tools, it would be hard to manage a UX project—rather like trying to build a house without a blueprint.

This workflow captures what’s going on in a project.

© Vishal S, Fair Use

Prototyping is a crucial part of the UX design process—it lets design teams create interactive visuals for user testing and stakeholder review. Most prototyping tools don't require coding experience, so they’re highly accessible to designers of all skill levels. Managers need to know the tools of their trade here. Many tools offer various features to enhance the design process—like animation libraries and solutions for creating design systems. Each tool is unique and suited to meet different needs, so designers can find the perfect fit for their projects and managers can be satisfied that the design team’s efforts can be even more on-point as a result.

UX designers typically can strengthen their case to move into UX project management roles if they:

Gain experience: It’s helpful to have 3-5 years of UX design experience—working on diverse projects and collaborating with cross-functional teams—and even more so to lead small projects or initiatives within their designer’s role.

Develop project management skills: It’s wise to get familiar with project management methodologies like Agile, Scrum or Waterfall and even think about obtaining certifications such as PMP (Project Management Professional) or PRINCE2.

Boost leadership abilities: Designers should work on how they practice effective communication, team management and conflict-resolution skills—hence why it’s wise to take on mentoring roles or lead design workshops.

Broaden knowledge: It’s helpful to understand the business side of UX—including budgeting, resource allocation and stakeholder management—and keep a finger on the pulse of industry trends and emerging technologies.

Pursue relevant education: Designers can think about pursuing advanced degrees in design management, business administration or project management to complement their design background.

This is one aspect of project management in UX design—how best to manage a product calls for a fusion of areas.

© Joca Torres, Fair Use

Network and seek mentorship: It’s helpful for designers to connect with UX project managers in their industry to get both valuable insights and potential opportunities.

Optimize their UX portfolios: Portfolios are essential vehicles both for designers to apply for design work and to transition into project management if they choose.

Design Director at Societe Generale CIB, Morgane Peng explains vital points about design portfolios:

Designers who want to become project managers should understand how they present their portfolio is a design challenge in itself. If they can show a full understanding of what went into the design projects they worked on, they’ll prove a grasp of UX project management that can help them stand out as candidates and serve them well in the new managerial roles they might win.

Designers should consider how they present their design work can translate into how they might present project management work to stakeholders.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Portfolios are a chance to showcase a well-rounded appreciation for what goes into a design project—including management processes and metrics or KPIs (key performance indicators). Designers who can prove their skill sets in research, collaboration, managing or handling clients or stakeholders, prototyping and other areas—and do it from a vantage point that exhibits a managerial point of view—will be much more likely to stand out as potential UX project leaders. That’s why it’s essential to show what went into each case study, for example, and not just the end results. Potential employers want to get a deep understanding of the thought processes that tackled challenges to reach that happy ending—a usable, desirable digital solution or service that can stand tall in the marketplace.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

UX project managers might well need to handle challenges that can derail even the most promising projects. Here are some common ones:

Scope creep: It’s vital to clearly define project scope from the outset and implement a change management process to keep project boundaries from expanding too far.

Poor communication between team members and stakeholders: Regular check-ins and transparent reporting are among the ways to keep healthy communication channels open.

Neglect for user research: It’s a critical mistake—one that can lead to products that fail to meet user needs and then fail utterly in the marketplace. It’s critical therefore to prioritize user testing and feedback throughout the development process—to make sure the final product really resonates with its intended audience.

William Hudson explains important points about usability testing:

Lack of stakeholder buy-in: This can massively hinder progress, too, and it’s crucial to engage stakeholders early and often and show them the value of UX decisions to get their support and manage their feedback effectively.

Design Director at Societe Generale CIB, Morgane Peng explains essential points about feedback:

Overall, UX project management is the guiding force that helps teams both to meet user needs and business goals and to stay on point through the design and development process. UX project managers oversee the entire process—from user research and design to implementation and testing—while they coordinate teams and resources as effectively as possible.

Management at this level is a demanding role but one that—as long as project managers perform their duties well—ensures the best decisions channel through all teams and parts of the process. When this happens, everyone involved in a project can be more likely to stand back after the brand releases their combined work and feel just as delighted as the users in their target audience will be.

Our course Build a Standout UX/UI Portfolio: Land Your Dream Job with Design Director at Societe Generale CIB, Morgane Peng provides a precious cache of details and tips for freelance designers.

Watch our Master Class, Design KPIs: From Insights to Impact with Vitaly Friedman, Senior UX Consultant, European Parliament, and Creative Lead, Smashing Magazine.

See our Topic Definition, What is Product Management? for important related details.

Go to our piece, Stakeholder Maps - Keep the Important People Happy for more helpful points.

Check out our piece, Transition into a UX Career: Top Insights for additional information.

Consult UX Project Management: Advice from Two Perspectives by Liz Hanson for further helpful tips.

Read UX Project Management: Streamline The User Experience by Nicholas Turturro for more details.

Look at The 25 project management skills you need to succeed by Julia Martins for additional helpful points.

A UX Project Manager typically earns between $80,000 and $120,000 annually in the United States, but the exact salary depends on factors like location, experience and the size of the company. The project manager vs UX designer salary is a question that extends to those with more experience or specialized skills in UX design and project management, as they can command higher pay, too. To bolster your earning potential, consider getting certifications or expanding your expertise in both UX and management to get more on the managerial side in the project management vs UX design money question.

Check out our piece, Transition into a UX Career: Top Insights for additional points.

First, define your goals and understand the problem you want to solve. Do research to collect as much information as possible about your users and their needs. Next, create user personas and journey maps to visualize your findings. Then, brainstorm and sketch ideas with your team—focusing on solutions that address user pain points. Develop wireframes and prototypes to test your concepts. Last—but not least—gather feedback from real users, iterate based on that feedback and refine your designs. A clear plan and strong user focus are key to a successful UX project.

UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains important points about UX research:

To start, break the project down into key phases like research, design, prototyping and testing. Estimate how long each phase will take based on the project's complexity and your team's experience—and factor in extra time for unexpected issues, revisions and feedback. Talk to your team to get their input and adjust your estimates as needed. Always build in some buffer time to handle delays without rushing; it’s only good—and fair—project management for designers and everyone else involved. Plan carefully and stay flexible, and you can set timelines that will really keep the project on track without overwhelming your team.

Watch our Master Class, Design KPIs: From Insights to Impact with Vitaly Friedman, Senior UX Consultant, European Parliament, and Creative Lead, Smashing Magazine.

Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains important and helpful advice regarding time management:

To start, list all your costs, including research, design tools, team salaries and any external resources like freelancers or software—and be sure to prioritize essential expenses and allocate funds with that firmly in mind. Track spending regularly—and if you notice any overspending, adjust your plans or reallocate funds from less-critical areas. Communicate with your team about the budget—so no unpleasant surprises arise—and it will make for more informed decisions, too. Keep a small reserve for unexpected costs. Overall, if you monitor your budget closely and make adjustments wisely, you’ll be able to manage your project finances well and help stay on track—and target—for success in design, project management and much more.

Watch our Master Class, Design KPIs: From Insights to Impact with Vitaly Friedman, Senior UX Consultant, European Parliament, and Creative Lead, Smashing Magazine.

CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers explains key points about a related topic, return on investment (ROI), which is helpful for managers to consider:

To start, understand their goals and concerns. Keep your updates clear and focused on how the design supports business objectives—being sure to use simple language and visuals like wireframes or prototypes to make complex ideas that much easier for them to grasp. Schedule regular meetings to share progress and get their feedback—and be sure you listen to their input and address their questions. You’ll need to be fully transparent about any challenges or changes—and, vitally, always explain the reasoning behind your design decisions. Clear, consistent communication builds trust and makes sure that everyone stays aligned throughout the project. Last—but not least—keep calm, courteous and organized. To stay organized and open to change is a particularly vital foundation; project management can be more efficient and effective that way, and stakeholders will be more likely to trust in your efforts.

Watch our Master Class, Win Clients, Pitches & Approval: Present Your Designs Effectively with Todd Zaki Warfel, Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach.

If a UX project starts to fall behind schedule, first assess the situation to identify the cause of the delay. Prioritize tasks by focusing on the most critical ones that impact the project's success. Communicate the issue to your team and stakeholders—immediately—so everyone is aware and can contribute to solutions. Adjust the timeline if you have to, but consider reallocating resources or streamlining certain processes to make up time, too. Stay flexible and open to making tough decisions—like cutting non-essential features. From taking proactive steps and keeping everyone informed, you can get the project back on track.

Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains important and helpful advice regarding time management:

Watch our Master Class, Design KPIs: From Insights to Impact with Vitaly Friedman, Senior UX Consultant, European Parliament, and Creative Lead, Smashing Magazine.

Mara, A., & Jorgenson, J. (2015). Mutt Methods, Minimalism, and Guiding Heuristics for UX Project Management. International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development, 7(3), 38-48.

This publication has been influential in the field of UX project management by proposing a flexible and tailored approach to managing UX projects. The authors recognize that UX is a multifaceted discipline with diverse perspectives and approaches—all united by a focus on the user. Instead of adhering to a single project management methodology (such as Agile, Lean, or Waterfall), they argue for a more adaptable approach that can be customized to the specific demands of each UX project.

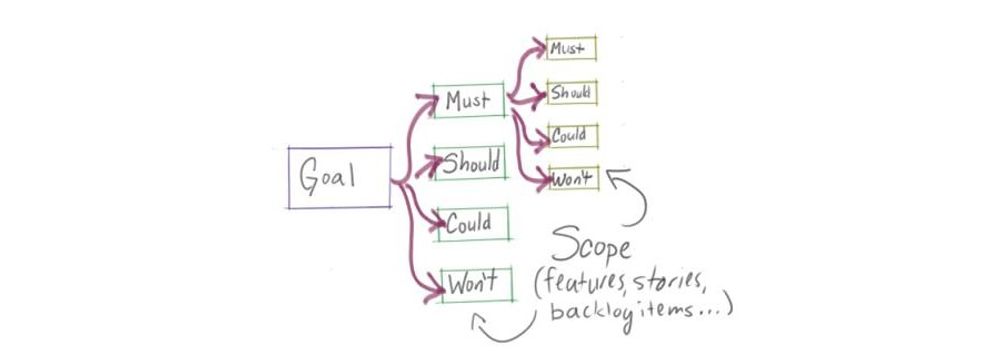

The paper introduces four key heuristics to help UX teams narrow their focus and determine the most appropriate project management approach: project scope, project agents, evaluation timing and evaluation criteria. By addressing these four areas, UX teams can better identify which project management techniques and genres will be most effective for their specific goals.

Unger, R., & Chandler, C. (2012). A Project Guide to UX Design: For User Experience Designers in The Field or in The Making (2nd ed.). New Riders.

A Project Guide to UX Design by Russ Unger and Carolyn Chandler has been highly influential in the field of UX design and project management. This comprehensive guide provides practical insights for both novice and experienced UX designers—offering a structured approach to managing UX projects from start to finish. The book covers a wide range of essential topics, including project planning, user research, information architecture, prototyping and working with stakeholders.

The book's influence stems from its ability to bridge the gap between theoretical UX knowledge and its application in professional settings. It offers actionable strategies and techniques that designers can immediately implement in their work. Its comprehensive coverage of UX design topics has made it a staple in many UX education programs and professional development reading lists.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Project Management by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Project Management with our course Build a Standout UX/UI Portfolio: Land Your Dream Job .

“Your portfolio is your best advocate in showing your work, your skills and your personality. It also shows not only the final outcomes but the process you took to get there and how you aligned your design decisions with the business and user needs.”

— Morgane Peng, Design Director, Societe Generale CIB

In many industries, your education, certifications and previous job roles help you get a foot in the door in the hiring process. However, in the design world, this is often not the case. Potential employers and clients want to see evidence of your skills and work and assess if they fit the job or design project in question. This is where portfolios come in.

Your portfolio is your first impression, your foot in the door—it must engage your audience and stand out against the hundreds of others they might be reviewing. Join us as we equip you with the skills and knowledge to create a portfolio that takes you one step closer to your dream career.

The Build a Standout UX/UI Portfolio: Land Your Dream Job course is taught by Morgane Peng, a designer, speaker, mentor and writer who serves as Director of Experience Design at Societe Generale CIB. With over 12 years of experience in management roles, she has reviewed thousands of design portfolios and conducted hundreds of interviews with designers. She has collated her extensive real-world knowledge into this course to teach you how to build a compelling portfolio that hiring managers will want to explore.

In lesson 1, you’ll learn the importance of portfolios and which type of portfolio you should create based on your career stage and background. You’ll discover the most significant mistakes designers make in their portfolios, the importance of content over aesthetics and why today is the best day to start documenting your design processes. This knowledge will serve as your foundation as you build your portfolio.

In lesson 2, you’ll grasp the importance of hooks in your portfolio, how to write them, and the best practices based on your career stage and target audience. You’ll learn how and why to balance your professional and personal biographies in your about me section, how to talk about your life before design and how to use tools and resources in conjunction with your creativity to create a unique and distinctive portfolio.

In lesson 3, you’ll dive into case studies—the backbone of your portfolio. You’ll learn how to plan your case studies for success and hook your reader in to learn more about your design research, sketches, prototypes and outcomes. An attractive and attention-grabbing portfolio is nothing without solid and engaging case studies that effectively communicate who you are as a designer and why employers and clients should hire you.

In lesson 4, you’ll understand the industry expectations for your portfolio and how to apply the finishing touches that illustrate your attention to detail. You’ll explore how visual design, menus and structure, landing pages, visualizations and interactive elements make your portfolio accessible, engaging and compelling. Finally, you’ll learn the tips and best practices to follow when you convert your portfolio into a presentation for interviews and pitches.

Throughout the course, you'll get practical tips to apply to your portfolio. In the "Build Your Portfolio" project, you'll create your portfolio strategy, write and test your hook, build a case study and prepare your portfolio presentation. You’ll be able to share your progress, tips and reflections with your coursemates, gain insights from the community and elevate each other’s portfolios.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!