Ethnography

Qualitative research is the methodology researchers use to gain deep contextual understandings of users via non-numerical means and direct observations. Researchers focus on smaller user samples—e.g., in interviews—to reveal data such as user attitudes, behaviors and hidden factors: insights which guide better designs.

“There are also unknown unknowns, things we don’t know we don’t know.”

— Donald Rumsfeld, Former U.S. Secretary of Defense

In this video, Alan Dix, Author of the bestselling book Human-Computer Interaction and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University, explains qualitative research.

Ah, well – it's a lovely day here in Tiree. I'm looking out the window again. But how do we know it's a lovely day? Well, I could – I won't turn the camera around to show you, because I'll probably never get it pointing back again. But I can tell you the Sun's shining. It's a blue sky. I could go and measure the temperature. It's probably not that warm, because it's not early in the year. But there's a number of metrics or measures I could use. Or perhaps I should go out and talk to people and see if there's people sitting out and saying how lovely it is

or if they're all huddled inside. Now, for me, this sunny day seems like a good day. But last week, it was the Tiree Wave Classic. And there were people windsurfing. The best day for them was not a sunny day. It was actually quite a dull day, quite a cold day. But it was the day with the best wind. They didn't care about the Sun; they cared about the wind. So, if I'd asked them, I might have gotten a very different answer than if I'd asked a different visitor to the island

or if you'd asked me about it. And it can be almost a conflict between people within HCI. It's between those who are more *quantitative*. So, when I was talking about the sunny day, I could go and measure the temperature. I could measure the wind speed if I was a surfer – a whole lot of *numbers* about it – as opposed to those who want to take a more *qualitative* approach. So, instead of measuring the temperature, those are the people who'd want to talk to people to find out more about what *it means* to be a good day.

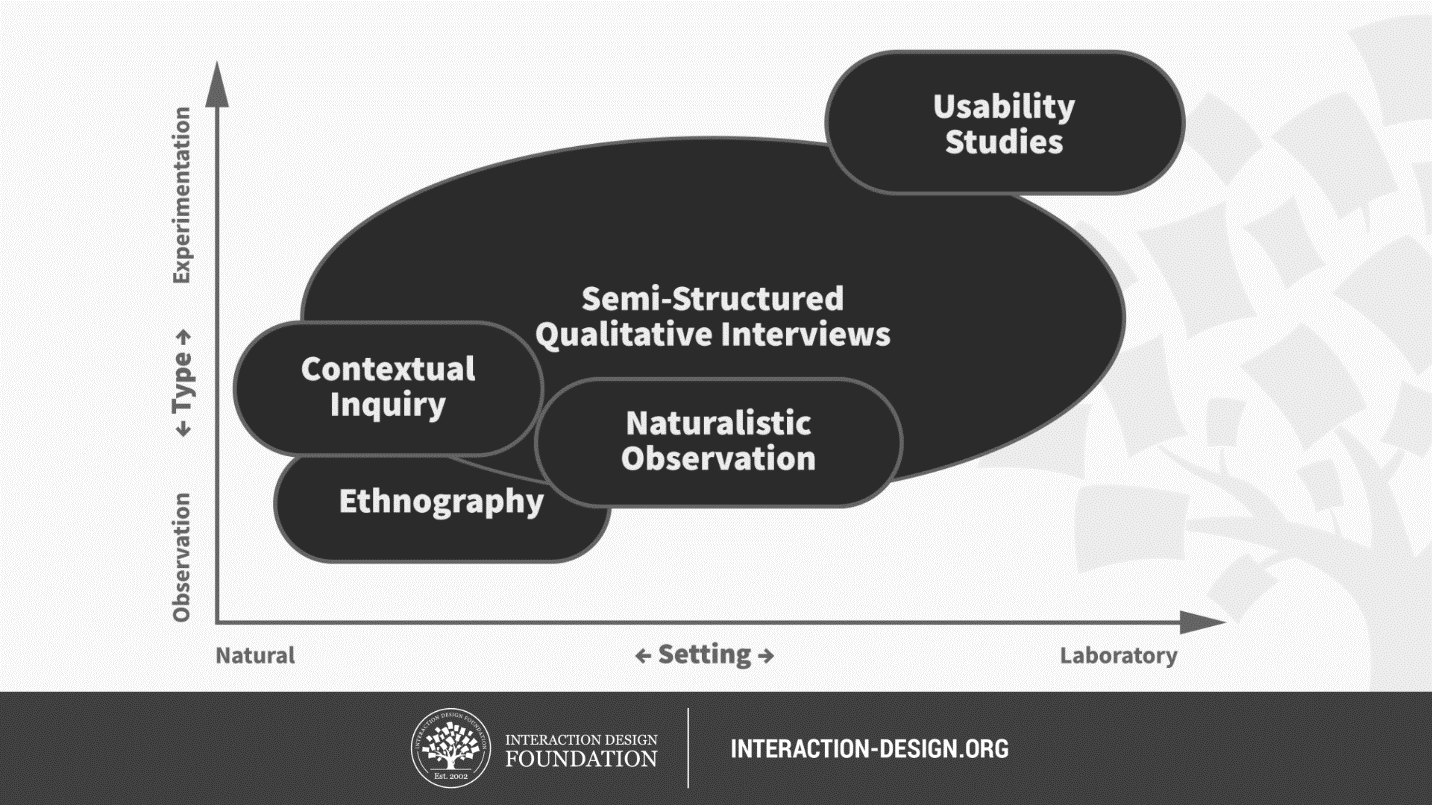

And we could do the same for an interface. I can look at a phone and say, "Okay, how long did it take me to make a phone call?" Or I could ask somebody whether they're happy with it: What does the phone make them feel about? – different kinds of questions to ask. Also, you might ask those questions – and you can ask this in both a qualitative and quantitative way – in a sealed setting. You might take somebody into a room, give them perhaps a new interface to play with. You might – so, take the computer, give them a set of tasks to do and see how long they take to do it. Or what you might do is go out and watch

people in their real lives using some piece of – it might be existing software; it might be new software, or just actually observing how they do things. There's a bit of overlap here – I should have mentioned at the beginning – between *evaluation techniques* and *empirical studies*. And you might do empirical studies very, very early on. And they share a lot of features with evaluation. They're much more likely to be wild studies. And there are advantages to each. In a laboratory situation, when you've brought people in,

you can control what they're doing, you can guide them in particular ways. However, that tends to make it both more – shall we say – *robust* that you know what's going on but less about the real situation. In the real world, it's what people often call "ecologically valid" – it's about what they *really* are up to. But it is much less controlled, harder to measure – all sorts of things. Very often – I mean, it's rare or it's rarer to find more quantitative in-the-wild studies, but you can find both.

You can both go out and perhaps do a measure of people outside. You might – you know – well, go out on a sunny day and see how many people are smiling. Count the number of smiling people each day and use that as your measure – a very quantitative measure that's in the wild. More often, you might in the wild just go and ask people. It's a more qualitative thing. Similarly, in the lab, you might do a quantitative thing – some sort of measurement – or you might ask something more qualitative – more open-ended. Particularly quantitative and qualitative methods,

which are often seen as very, very different, and people will tend to focus on one *or* the other. *Personally*, I find that they fit together. *Quantitative* methods tend to tell me whether something happens and how common it is to happen, whether it's something I actually expect to see in practice commonly. *Qualitative* methods – the ones which are more about asking people open-ended questions – either to both tell me *new* things that I didn't think about before,

but also give me the *why* answers if I'm trying to understand *why* it is I'm seeing a phenomenon. So, the quantitative things – the measurements – say, "Yeah, there's something happening. People are finding this feature difficult." The qualitative thing helps me understand what it is about it that's difficult and helps me to solve it. So, I find they give you *complementary things* – they work together. The other thing you have to think about when choosing methods is about *what's appropriate for the particular situation*. And these things don't always work.

Sometimes, you can't do an in-the-wild experiment. If it's about, for instance, systems for people in outer space, you're going to have to do it in a laboratory. You're not going to go up there and experiment while people are flying around the planet. So, sometimes you can't do one thing or the other. It doesn't make sense. Similarly, with users – if you're designing something for chief executives of Fortune 100 companies, you're not going to get 20 of them in a room and do a user study with them.

That's not practical. So, you have to understand what's practical, what's reasonable and choose your methods accordingly.

See how you can use qualitative research to expose hidden truths about users and iteratively shape better products.

Qualitative research is a subset of user experience (UX) research and user research. By doing qualitative research, you aim to gain narrowly focused but rich information about why users feel and think the ways they do. Unlike its more statistics-oriented “counterpart”, quantitative research, qualitative research can help expose hidden truths about your users’ motivations, hopes, needs, pain points and more to help you keep your project’s focus on track throughout development. UX design professionals do qualitative research typically from early on in projects because—since the insights they reveal can alter product development dramatically—they can prevent costly design errors from arising later. Compare and contrast qualitative with quantitative research here:

Qualitative research | Quantitative Research | |

You Aim to Determine | The “why” – to get behind how users approach their problems in their world | The “what”, “where” & “when” of the users’ needs & problems – to help keep your project’s focus on track during development |

Methods | Loosely structured (e.g., contextual inquiries) – to learn why users behave how they do & explore their opinions | Highly structured (e.g., surveys) – to gather data about what users do & find patterns in large user groups |

Number of Representative Users | Often around 5 | Ideally 30+ |

Level of Contact with Users | More direct & less remote (e.g., usability testing to examine users’ stress levels when they use your design) | Less direct & more remote (e.g., analytics) |

Statistically | You need to take great care with handling non-numerical data (e.g., opinions), as your own opinions might influence findings | Reliable – given enough test users |

Regarding care with opinions, it’s easy to be subjective about qualitative data, which isn’t as comprehensively analyzable as quantitative data. That’s why design teams also apply quantitative research methods, to reinforce the “why” with the “what”.

You have a choice of many methods to help gain the clearest insights into your users’ world – which you might want to complement with quantitative research methods. In iterative processes such as user-centered design, you/your design team would use quantitative research to spot design problems, discover the reasons for these with qualitative research, make changes and then test your improved design on users again. The best method/s to pick will depend on the stage of your project and your objectives. Here are some:

Diary studies – You ask users to document their activities, interactions, etc. over a defined period. This empowers users to deliver context-rich information. Although such studies can be subjective—since users will inevitably be influenced by in-the-moment human issues and their emotions—they’re helpful tools to access generally authentic information.

Interviews – These are either structured, semi-structured, or ethnographic:

Structured – You ask users specific questions and analyze their responses with other users’.

Semi-structured – You have a more free-flowing conversation with users, but still follow a prepared script loosely.

Ethnographic – You interview users in their own environment to appreciate how they perform tasks and view aspects of tasks.

Usability testing

Moderated – In-person testing in, e.g., a lab.

Unmoderated – Users complete tests remotely: e.g., through a video call.

Guerrilla – “Down-the-hall”/“down-and-dirty” testing on a small group of random users or colleagues.

User observation – You watch users get to grips with your design and note their actions, words and reactions as they attempt to perform tasks.

Qualitative research can be more or less structured depending on the method.

Some helpful points to remember are:

Participants – Select a number of test users carefully (typically around 5). Observe the finer points such as body language. Remember the difference between what they do and what they say they do.

Moderated vs. unmoderated – You can obtain the richest data from moderated studies, but these can involve considerable time and practice. You can usually conduct unmoderated studies more quickly and cheaply, but you should plan these carefully to ensure instructions are clear, etc.

Types of questions – You’ll learn far more by asking open-ended questions. Avoid leading users’ answers – ask about their experience during, say, the “search for deals” process rather than how easy it was. Try to frame questions so users respond honestly: i.e., so they don’t withhold grievances about their experience because they don’t want to seem impolite. Distorted feedback may also arise in guerrilla testing, as test users may be reluctant to sound negative or to discuss fine details if they lack time.

Location –Think how where users are might affect their performance and responses. If, for example, users’ tasks involve running or traveling on a train, select the appropriate method (e.g., diary studies for them to record aspects of their experience in the environment of a train carriage and the many factors impacting it).

Another approach to get reliable research is grounded theory. It helps to reduce bias and discover your users’ true needs and behaviors. In this video, William Hudson, User Experience Strategist and Founder of Syntagm Ltd, explains more.

Grounded theory is a well-known approach to qualitative research from the social and psychological research areas. It started around about the late 1960s with Glaser and Strauss, whose book, about the subject is really the original bible for it. It is research without preconceptions. It's very open in that respect. You're not trying to find out,

answers to specific questions; you're trying to find out how people behave in particular problem domains. So, for persona research, really, it's ideal. And the basic principle of grounded theory, the way that it's executed, is that researchers alternate between data collection and analysis. We go out, and we do interviews. We come back with lots of interview notes, recordings if possible, and we try to make sense of it. And that sense involves seeing how

much information overlaps between the various interviews. And if we find some areas which have scant overlap, if that area is of interest to us, we might want to go and ask about those particular areas in other interviews or even go back to the original participants and ask them to provide us with a bit more information on that. I've certainly done that, discovered new things

later on, and gone back and spoken to participants again about those new topics to find out whether those were of interest or were involved in their own dealings in that particular problem domain.

Overall, no single research method can help you answer all your questions. Nevertheless, The Nielsen Norman Group advise that if you only conduct one kind of user research, you should pick qualitative usability testing, since a small sample size can yield many cost- and project-saving insights. Always treat users and their data ethically. Finally, remember the importance of complementing qualitative methods with quantitative ones: You gain insights from the former; you test those using the latter.

Learn how to turn your user research into personas that foster empathy, align teams, and drive user-centered design in our course, Personas and User Research: Design Products and Services People Need and Want.

Take our course on User Research to see how to get the most from qualitative research.

Read about the numerous considerations for qualitative research in this in-depth piece.

This blog discusses the importance of qualitative research, with tips.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Qualitative Research by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Qualitative Research with our course User Research – Methods and Best Practices .

How do you plan to design a product or service that your users will love, if you don't know what they want in the first place? As a user experience designer, you shouldn't leave it to chance to design something outstanding; you should make the effort to understand your users and build on that knowledge from the outset. User research is the way to do this, and it can therefore be thought of as the largest part of user experience design.

In fact, user research is often the first step of a UX design process—after all, you cannot begin to design a product or service without first understanding what your users want! As you gain the skills required, and learn about the best practices in user research, you’ll get first-hand knowledge of your users and be able to design the optimal product—one that’s truly relevant for your users and, subsequently, outperforms your competitors’.

This course will give you insights into the most essential qualitative research methods around and will teach you how to put them into practice in your design work. You’ll also have the opportunity to embark on three practical projects where you can apply what you’ve learned to carry out user research in the real world. You’ll learn details about how to plan user research projects and fit them into your own work processes in a way that maximizes the impact your research can have on your designs. On top of that, you’ll gain practice with different methods that will help you analyze the results of your research and communicate your findings to your clients and stakeholders—workshops, user journeys and personas, just to name a few!

By the end of the course, you’ll have not only a Course Certificate but also three case studies to add to your portfolio. And remember, a portfolio with engaging case studies is invaluable if you are looking to break into a career in UX design or user research!

We believe you should learn from the best, so we’ve gathered a team of experts to help teach this course alongside our own course instructors. That means you’ll meet a new instructor in each of the lessons on research methods who is an expert in their field—we hope you enjoy what they have in store for you!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!