'Affordance' is a term most designers will have come across at some stage of their studies and careers. Don Norman introduced this term to the design community.

Despite Don Norman’s best efforts, the underlying meaning of the term is sometimes misunderstood.

How to define 'Affordance'

Don Norman first mentioned affordances in the context of design in The Design of Everyday Things (1988). Norman borrowed the term and concept from the world of James J. Gibson (1977; 1979), a prominent perceptual psychologist, but modified the meaning slightly to make it more appropriate for use by designers. Gibson originally used the term to describe "...the actionable properties between the world and an actor [user]" (Norman, Affordances and Design).

Gibson's definition essentially identifies the powerful relationship between man and things. Whether through experience or some innate ability (we will leave this debate for another day), we are capable of assessing objects according to their perceptible properties. These interpretations allow us to both determine an object's possible uses and analyse how they might help us achieve our aims and objectives. For example, just by looking at a glass we can determine that the object affords holding liquid, so we can quench our thirst. Some affordances are less obvious, and many yet to be realised, but with objects in the real, physical world, there is a natural and direct relationship between the perceptible qualities of tangible things and what we can do with them.

The Evolution of "Affordances"

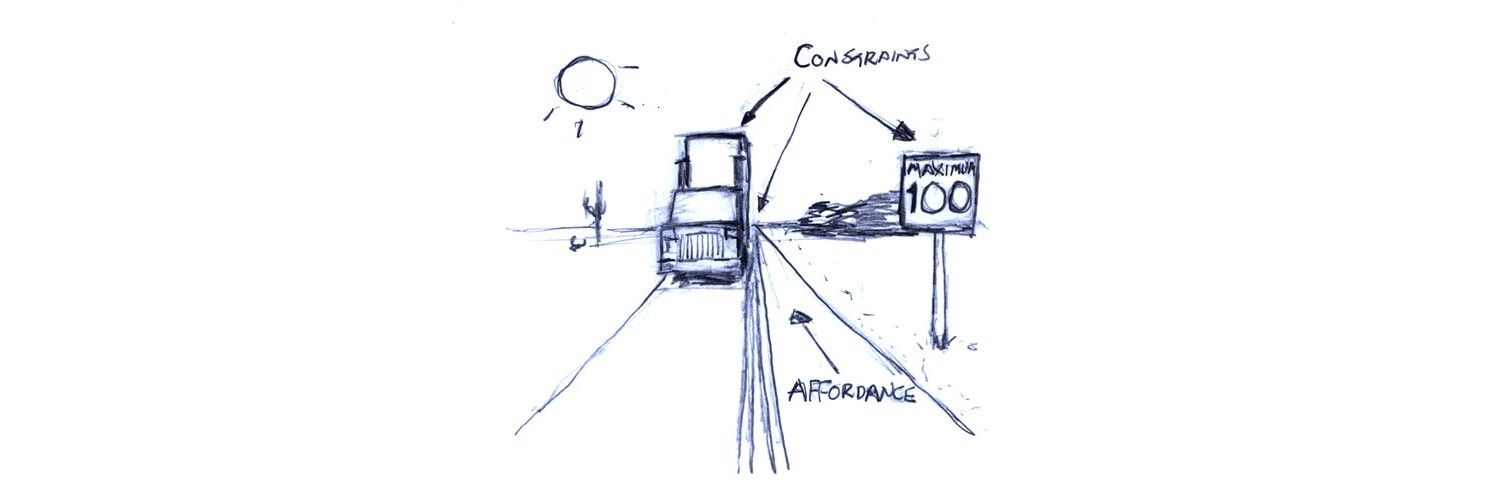

In design, we cannot rely on this natural relationship. Aside from touchscreens, interactive elements in screen-based interfaces have affordances that exist in the virtual world alone, and the means of interaction are almost exclusive to this domain. Norman referred to the affordances found in screen-based interfaces as 'perceived', on the grounds that users form and develop notions of what they can do according to conventions, constraints, and visual, auditory, and sometimes haptic feedback.

Norman's distinction between real and perceived affordances is an important one for designers, especially those involved in the development of graphical user interfaces. While we have tacit knowledge of how the perceptible characteristics of physical objects will be interpreted, the design of graphical elements requires an understanding of what the user assumes or perceives will occur as a result of their interaction(s).

Perceived Affordances in Graphical User Interfaces

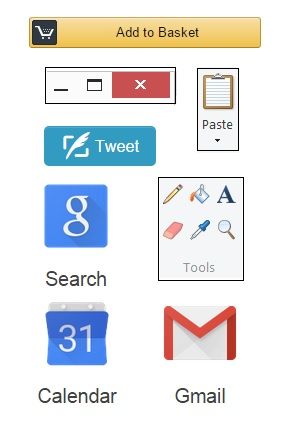

Author/Copyright holder: Z.Evelyn. Copyright terms and license: All rights reserved Img source

For experienced users, interacting with screen-based interfaces is an activity often taken for granted. You know where and when to click at each stage of a task, that desktop icons must be double-clicked to open the contents, red squares with an embedded white cross signify that clicking will close the window, panel, or page, and that right clicking on the screen (at most points) will usually reveal a sub-set of options, such as 'back', 'reload', 'save as...', and 'print' on a webpage. In contrast to the real affordances found in the physical world, these are learned conventions that are revealed or signified by established, consistent, but artificial, cues.

At most points during human-computer interaction, users are able to move a cursor - or pointer of some sort - to click on all parts of the screen and tap the keys on their keyboard, but whether these actions are meaningful or have any effect on the screen, system, or software is dependent on what has been programmed. The designer must, therefore, provide explicit cues (and as the user becomes more experienced and proficient, implicit cues) that help the user determine what effect(s) their interactions will have, when to carry out specific actions, and to help them establish whether these actions have been successful/unsuccessful.

Identifying Real and Perceived Affordances

Our ability to identify affordances in the real-world is constrained almost solely by our current drives and motivations (or our imagination). For example, when asked to identify the affordances of a kitchen towel we might think of the primary uses, such as drying, wiping, and for heat-protection when taking something hot from the oven. However, in a different situation, we would be capable of finding alternative uses for the kitchen towel, such as using it to put out a pan fire, or to prevent a chopping board from sliding.

In contrast, graphical objects and interactive elements are much less flexible; we can usually left/right click, double-click, hold down a button and drag, or use the keyboard, but the actual results of these actions are constrained by the interface. For this reason, users' actions are based on predictions, which are only confirmed once the action has been carried out.

Perceived Affordances and Consistency

If users are to instantly identify the interactive elements on a screen, and accurately predict the results of their interactions, the interface must work according to their expectations. These expectations are based on prior experience with other products. By conforming to the design traditions, such as those mentioned above, the user is able to apply knowledge from one interface to another. Conversely, inconsistencies will more than likely lead to inaccurate predictions and errors as a direct result.

Consistency across different interfaces is important, but if you are dealing with new or innovative products, you may introduce new or unfamiliar actions. When this is the case, consistency is still essential, as the user must be able to apply their understanding of the perceived affordances from one situation to another within the same product. For example, consider a computer game where the player can pick up a number of different objects; if there were a different action or set of button presses for each specific object there is far greater potential for user error, as there are multiple methods of interaction to achieve the same result in the game (i.e. picking something up).

Affordances and Modern Technology

Traditionally, perceived affordances are based on domain-specific conventions and consistency, but in the last ten to twenty years, and especially with the evolution of touchscreens, designers have been taking inspiration from real affordances to allow the application of knowledge from the real-world to the virtual world. Users are now able to touch (e.g. Apple products), shake (e.g. Nintendo Wii controllers), blow (e.g. the Nintendo DS), swipe (e.g. e-Readers), and rotate (e.g. computer controllers) objects to influence events in the virtual world in a way that match the corresponding activities in the real-world.

The use of real-world affordances as inspiration in the design of products in human-computer interaction may present the possibility of a smooth passage from the physical to the virtual world. However, it also has the potential to influence the user negatively; especially, if the required behaviours are similar but the resulting events are unpredictable, or the necessary actions inaccurately reflect those activities we would carry out in the physical world.

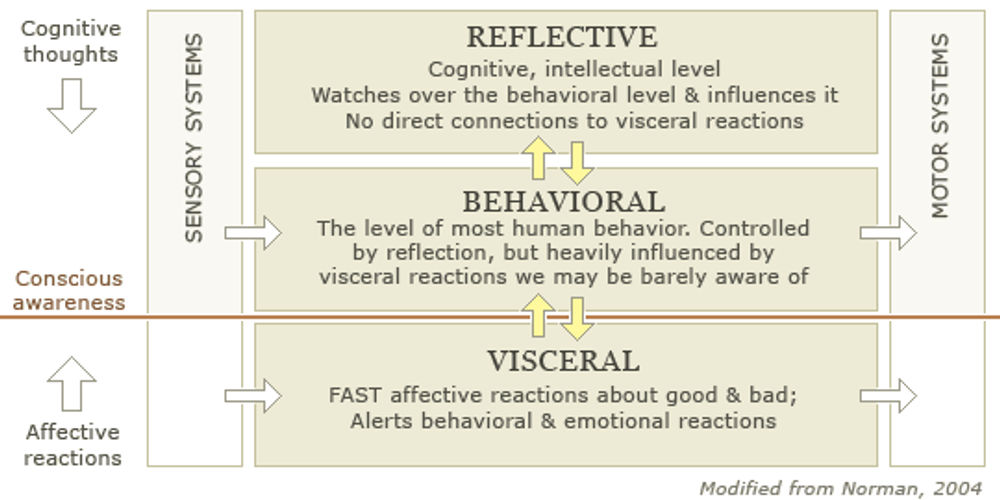

Whichever approach designers adopt, their users must be able to develop an accurate view of the interface, so they can instantly and unconsciously predict the effect(s) of their actions to achieve as stable and predictable a relationship as that found between man and things in the real-world.

References & Where to Learn More

Header Image: Author/Copyright holder: Dorian Taylor. Copyright terms and licence: All rights reserved. Img