Heuristic evaluation is the activity of using a set of guidelines (heuristics) to evaluate if an interface is user-friendly. Let’s look at what heuristics are and how you can conduct a heuristic evaluation to improve the usability of your designs.

What are Heuristics?

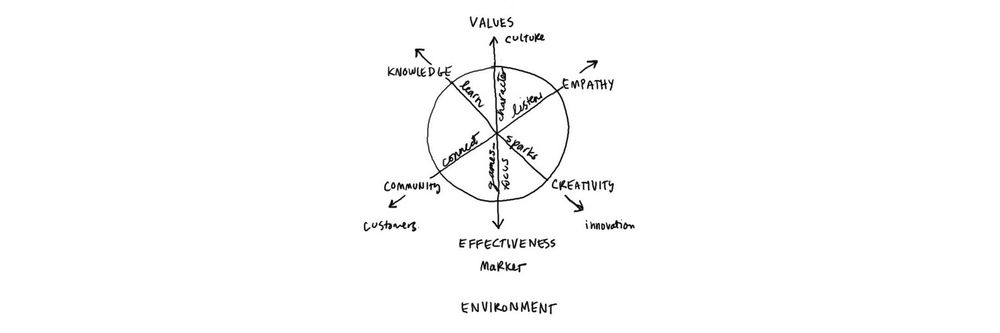

“Heuristics” simply means guidelines. In user experience design, it is nearly impossible to define rigid rules. There is no fool-proof way to create experiences that are guaranteed to work. Instead, you can refer to principles to guide you in your design process, to help you evaluate your work before you test it with real users.

Several researchers and leaders have proposed different sets of guidelines for user interface design. Let’s look at one of the most popular guidelines proposed by Jakob Nielsen and Rolf Molich.

Nielsen and Molich's 10 User Interface Design Heuristics

Jakob Nielsen, a usability consultant and partner in the Nielsen Norman Group, and Rolf Molich, usability engineer and founder of DialogDesign, established a list of ten user interface design guidelines in the 1990s.

In this video, William Hudson explains each of these heuristics, along with illustrative examples.

Show

Hide

video transcript

- Transcript loading…

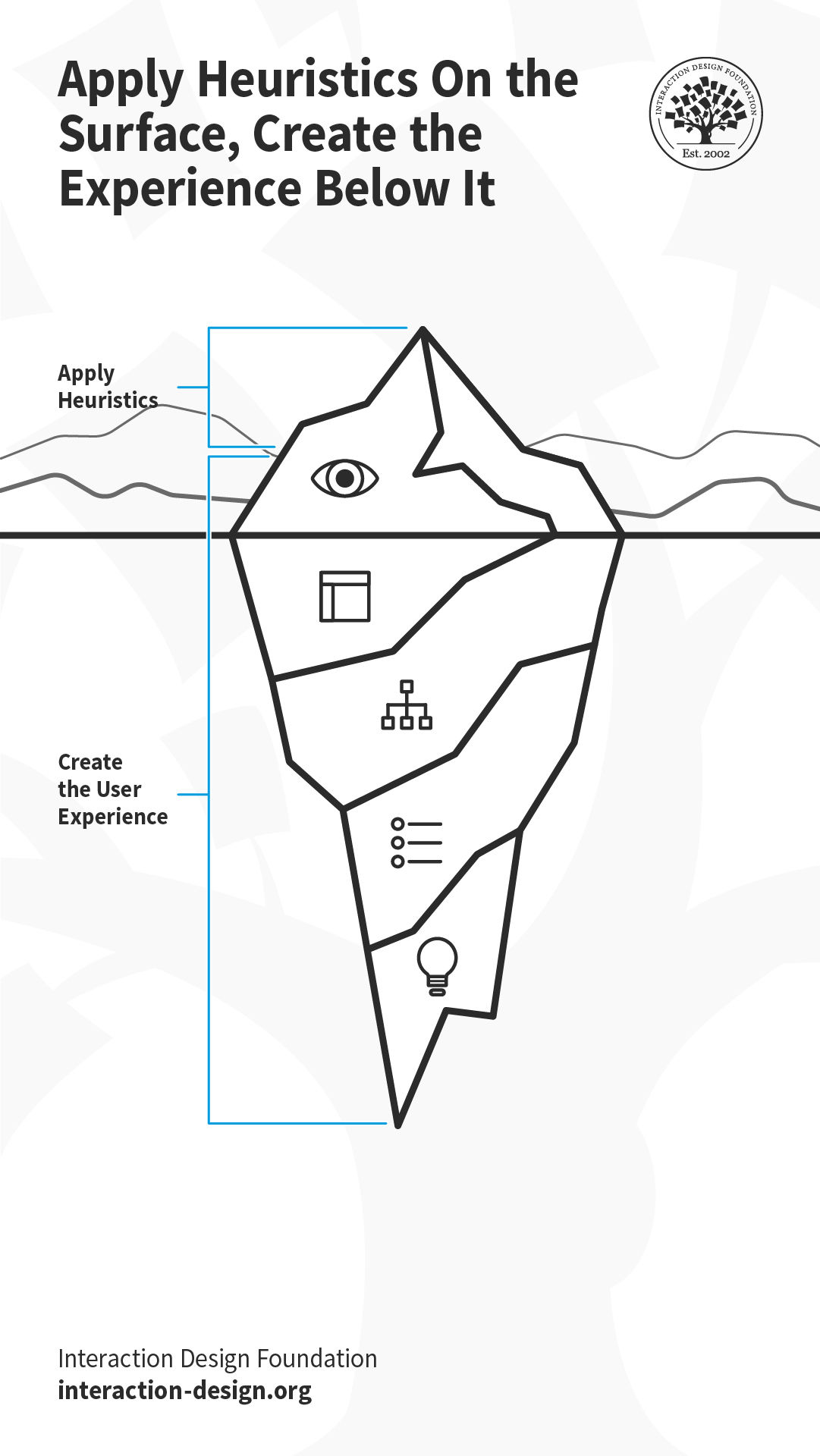

These heuristics are applied at the “Surface” element of the user’s experience. However, user experience is created by design decisions taken at the strategy (why and for whom are you building the solution?), scope (what is it that you’re building?) and the structure and skeleton (how does the solution work?) levels. So, it is helpful to keep heuristics in mind throughout the design process. Let’s say you are creating the user flow for a task in a mobile application (the structure). If you map the task flow close to the real-world task that users are already familiar with (heuristic #2: match between system and the real world), your interface (the surface) will be more likely to adhere to this heuristic.

What the user sees at the surface is only the tip of the metaphorical iceberg, which is influenced by the decisions taken below the “surface of the ocean.”

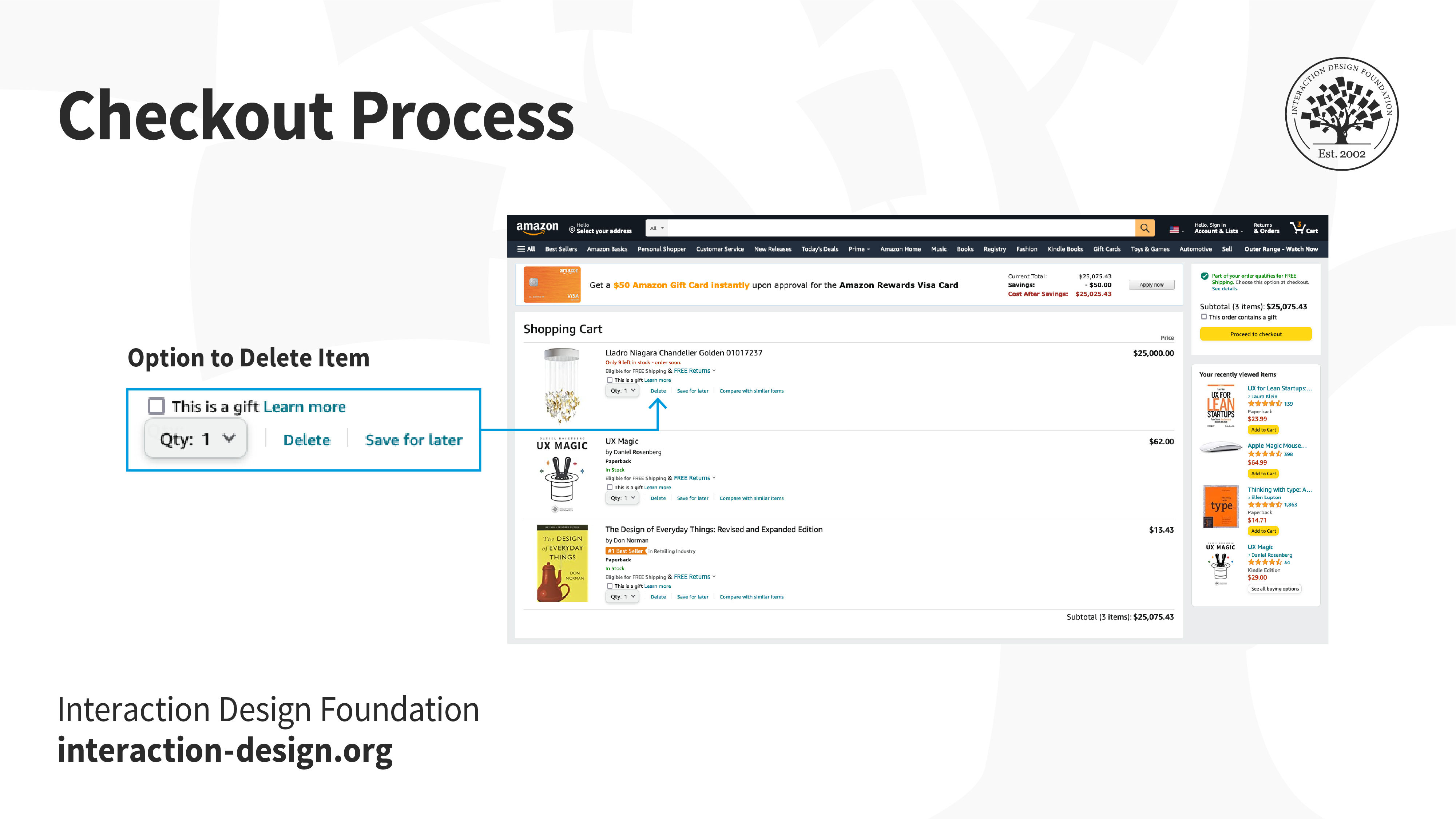

When you go shopping at the grocery store, sometimes you realize you’ve added extra items that you can do without, and take them out before reaching the checkout counter. Or, perhaps you request the cashier to remove an item even after they have billed it, realizing it is far too expensive. When designing the online version of the checkout process, your architecture should therefore support the back-and-forth movement between the different parts of the checkout process and the interface will need to as well.

Amazon’s information architecture allows users to remove items at any point before and during the checkout process, even after the user has entered the payment method and shipping information, which is reflected in the interface.

Adapting Heuristics to Your Context

Technology has changed drastically since Nielsen and Molich first wrote the heuristics. For example, mobile devices and voice-based smart devices demand more context-specific heuristics. That said, Nielsen and Molich’s principles have stood the test of time and continue to be relevant. For example, on a voice-based interface, the heuristic “visibility of the system status” continues to be relevant; what changes is how you implement it (perhaps through a flickering light, or a dedicated sound effect). As new technology continues to emerge, you must learn how to adapt these heuristics to the new technologies, and if required, extend or add to the heuristics. For instance, ergonomics and judicious use of screen real estate are heuristics specific to mobile devices.

How to Conduct a Heuristic Evaluation

Establish an appropriate list of heuristics. You can choose Nielsen and Molich's 10 heuristics or another set, such as Ben Shneiderman’s 8 golden rules as inspiration and stepping stones. Make sure to combine them with other relevant design guidelines and market research.

Select your evaluators. Make sure to carefully choose your evaluators. Your evaluators should not be your end users. They should typically be usability experts and preferably with domain expertise in the industry type that your product is in. For example, an evaluator investigating a Point-of-Sale system for the restaurant industry should have at least a general understanding of restaurant operations.

Brief your evaluators so they know exactly what they are meant to do and cover during their evaluation. The briefing session should be standardized to ensure the evaluators receive the same instructions; otherwise, you may bias their evaluation. Within this brief, you may wish to ask the evaluators to focus on a selection of tasks, but sometimes they may state which ones they will cover based on their experience and expertise.

First evaluation phase. The first evaluation generally takes around two hours, depending on the nature and complexity of your product. The evaluators will use the product freely to gain a feel for the methods of interaction and the scope. They will then identify specific elements that they want to evaluate.

Second evaluation phase. In the second evaluation phase, the evaluators will carry out another run-through, whilst applying the chosen heuristics to the elements identified during the first phase. The evaluators would focus on individual elements and look at how well they fit in the overall design.

Record problems. The evaluators must either record problems themselves or you should record them as they carry out their various tasks to track any problems they encounter. Be sure to ask the evaluators to be as detailed and specific as possible when recording problems.

Debriefing session. The debriefing session involves collaboration between the different evaluators to collate their findings and establish a complete list of problems. They should then be encouraged to suggest potential solutions for these problems based on the heuristics.

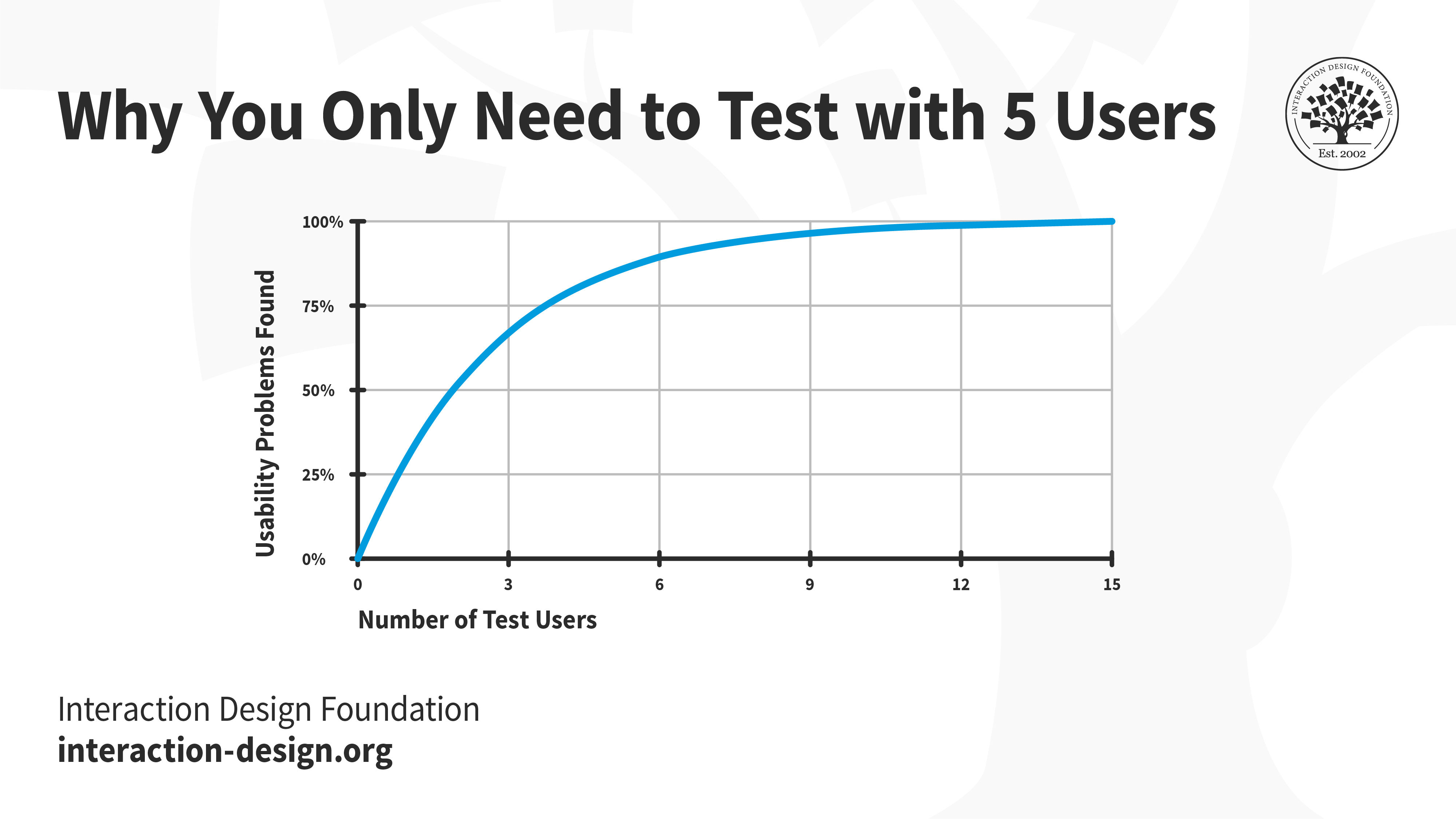

In general, the more evaluators you have, the more usability issues you will unearth, especially when the evaluators have different skill sets. However, Jakob Nielsen suggests that between three and five evaluators is sufficient. With five evaluators, you should be able to identify up to 75% of all issues. While increasing the number of evaluators will help you find more issues, it may not be worth the time and effort.

Jakob Nielsen’s research indicates that five evaluators can help you discover about 75% of the usability issues. Beyond five, with every additional evaluator, the proportion of new usability issues will be much smaller and usually not worth the extra resources.

Pros and Cons of Heuristic Evaluation

Like any suggested method in research and design, there are both pros and cons in the usability inspection method of heuristic evaluation. Let’s examine a few of them:

Pros of Heuristic Evaluation

Heuristics can help highlight potential usability issues early in the design process.

It is a fast and inexpensive tool compared with other methods involving real users.

Cons of Heuristic Evaluation

Heuristic evaluation depends on the knowledge and expertise of the evaluators. Training the evaluators or hiring external evaluators might increase the time and money required for conducting the evaluation.

Heuristic evaluation is based on assumptions about what “good” usability is. As heuristics are based on research, this is often true. However, the evaluations are no substitute for testing with real users. These are, as the name suggests, only guidelines, and not rules that are set in stone.

Heuristic evaluation can end up giving false alarms. In their article, “Usability testing vs. heuristic evaluation: A head-to-head comparison,” Robert Bailey, Robert Allan and P. Raiello found that 43% of 'problems' identified by experimental heuristic evaluations were not actually problems. Furthermore, evaluators could only identify 21% of genuine usability problems in comparison with usability testing.

Start conducting your own heuristic evaluations with the help of this template:

The Take Away

In user experience design, there are no hard rules that guarantee success. Instead, there are general guidelines, principles, or rules of thumb that you use to inform and evaluate your work. These guidelines are called heuristics, and when you evaluate your (or your competitor’s) work against these heuristics, it is called heuristic evaluation.

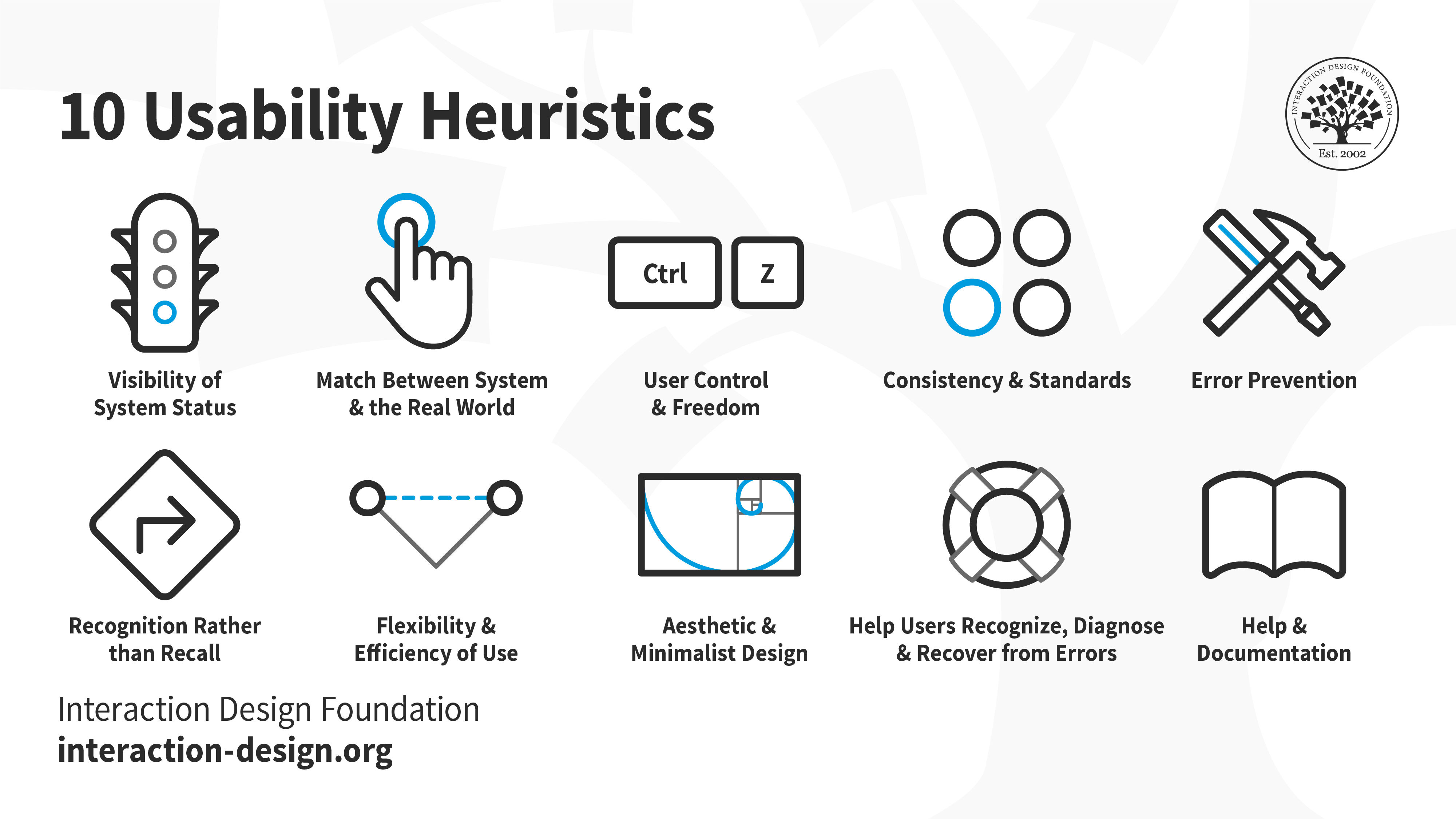

One of the most popular sets of heuristics are those created by Jakob Nielsen and Rolf Molich. These are:

Visibility of system status: Keep the user informed about what is happening behind the scenes.

Match between system and the real world: Ensure the conventions you use match what the user is already familiar with in the real world.

User control and freedom: Allow users to step back, undo and redo their actions.

Consistency and standards: Ensure interface elements like labels and icons behave consistently throughout the product.

Error prevention: Anticipate, and plan for errors. Where possible, eliminate them; and for other cases, ensure users can easily recover from errors.

Recognition rather than recall: Do not expect users to remember or recall information. It is always easier to recall information when we have clues to point us towards it. For example, it is easier for us to pick (i.e., recognize) the right answer from a list of options, rather than attempting to answer from memory (recall). Make sure your interface has cues to help users recognize information.

Flexibility and efficiency of use: Allow users to customize or tailor the interface to suit their needs so that they can perform frequent actions more easily.

Aesthetic and minimalist design: Remove clutter and any superfluous information so that users can focus on achieving their goal, instead of getting confused or overwhelmed.

Help users recognize, diagnose and recover from errors: Avoid technical jargon. Write error messages in plain language and ensure nothing gets lost in translation.

Help and documentation: Provide easily accessible and searchable documentation.

An illustration depicting Jakob Nielsen's 10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design. They’re called "heuristics" because they are broad rules of thumb and not specific usability guidelines.

Heuristic evaluation can be a useful inspection method; however, some experts have identified issues with evaluators reporting false alarms, rather than genuine problem elements within designs. To limit the effect misreporting has on the applicability of findings from heuristic evaluation, it helps to use a number of different evaluators, collate their problems and carry out a debriefing session to root out false alarms at various stages in the design process.

Heuristic evaluation is one of the many tools to guide your design process. However, it is not the only one that you should rely on. Make sure you conduct user research and test your designs with real users to continually refine your work.

References and Where To Learn More

Read the article Shneiderman’s Eight Golden Rules Will Help You Design Better Interfaces.

Images

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0