Understand the Elements and Thinking Modes that Create Fruitful Ideation Sessions

- 802 shares

- 5 years ago

Lateral thinking is a form of ideation in which designers approach problems by using disruptive or not immediately obvious reasoning. They use indirect and creative methods to think outside the box and see problems from radically new angles, gaining insights to help find innovative solutions.

“You cannot dig a hole in a different place by digging the same hole deeper.”

— Dr. Edward de Bono, Brain-training pioneer who devised lateral thinking

See how lateral thinking can stretch towards powerful, “impossible” solutions:

Many problems (e.g., mathematical ones) require the vertical, analytical, step-by-step approach we’re so familiar with. Called linear thinking, it’s based on logic, existing solutions and experience: You know where to start and what to do to reach a solution, like following a recipe. However, many design problems—particularly, wicked problems—are too complex for this critical path of reasoning. They may have several potential solutions. Also, they won’t offer clues; unless we realize our way of thinking is usually locked into a tight space and we need a completely different approach.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

That’s where lateral thinking comes in – essentially thinking outside the box. “The box” refers to the apparent constraints of the design space and our limited perspective from habitually meeting problems head-on and linearly. Designers often don’t realize what their limitations are when considering problems – hence why lateral thinking is invaluable in (e.g.) the design thinking process. Rather than be trapped by logic and assumptions, you learn to stand back and use your imagination to see the big picture when you:

Focus on overlooked aspects of a situation/problem.

Challenge assumptions – to break free from traditional ways of understanding a problem/concept/solution.

Seek alternatives – not just alternative potential solutions, but alternative ways of thinking about problems.

When you do this, you tap into disruptive thinking and can turn an existing paradigm on its head. Notable examples include:

The mobile defibrillator and mobile coronary care – Instead of trying to resuscitate heart-attack victims once they’re in hospital, treat them at the scene.

Uber – Instead of investing in a fleet of taxicabs, have drivers use their own cars.

Rather than focus on channeling more resources into established solutions to improve them, these innovators assessed their problems creatively and uncovered game-changing (and life-changing) insights.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

For optimal results, use lateral thinking early in the divergent stages of ideation. You want to reframe the problem and:

Understand what’s constraining you and why.

Find new strategies to solutions and places/angles to start exploring.

Find the apparent edges of your design space and push beyond them – to reveal the bigger picture.

You can use various methods. A main approach is provocations: namely, to make deliberately false statements about an aspect of the problem/situation. This could be to question the norms through contradiction, distortion, reversal (i.e., of assumptions), wishful thinking or escapism, for example:

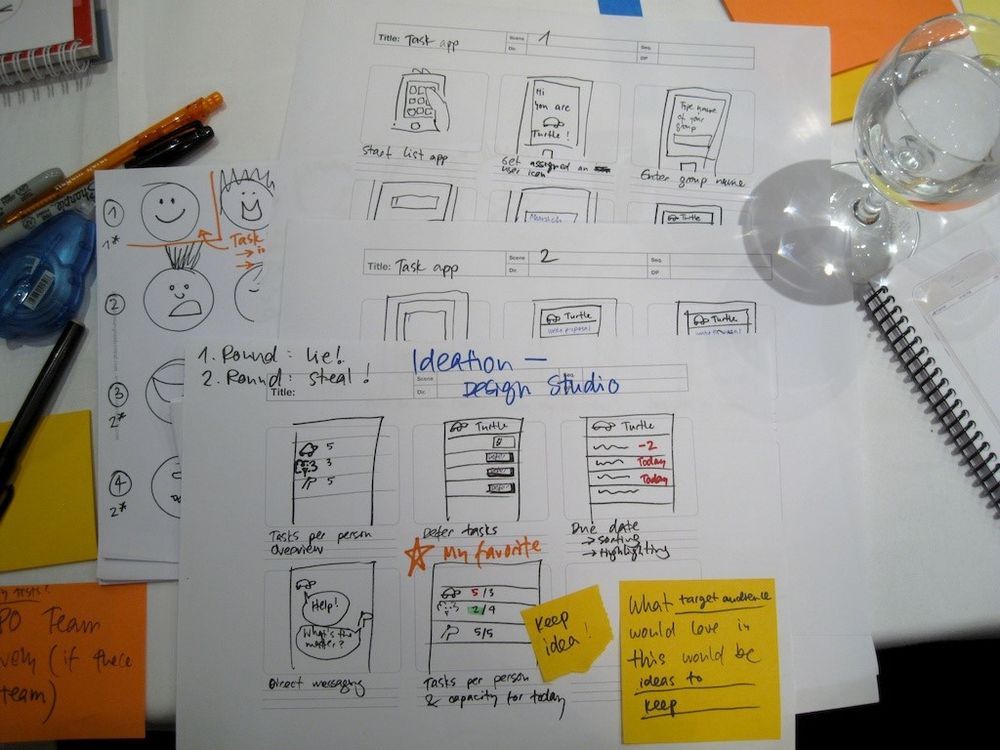

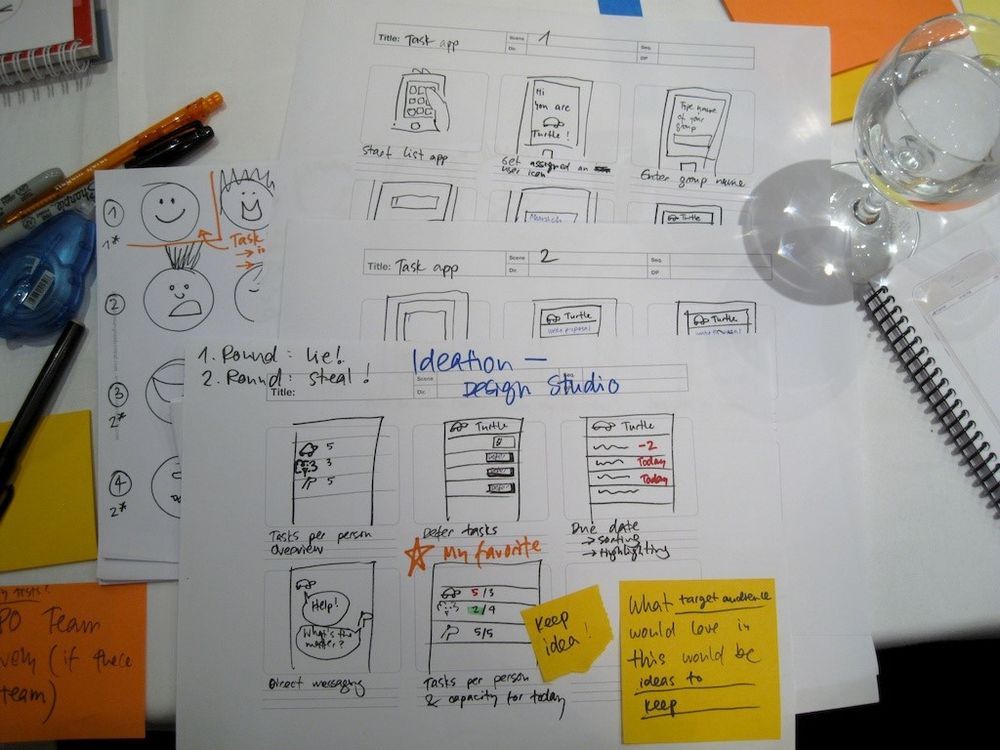

Here, we see the norm of conventional schooling challenged and some unpredictable (and even outrageous) notions to trigger our thinking. Our example showcases this method:

Bad Ideas – You think up as many bad or crazy ideas as possible, but these might have potentially good aspects (e.g., helping children specialize in desired subjects earlier). You also establish why bad aspects are bad (e.g., inserting biochips would be a gross violation of human rights).

Other helpful methods include:

Random Metaphors

Randomly pick an item near you or word from a dictionary and write down as many aspects/associations about it as possible. E.g., “Exhibition” – “visitors walk around enjoying paintings”; “learn about cultures”; “pleasant environment”.

Pretend some genius in your field told you this item/word is a good metaphor for your project. E.g., you can organize information, tips and images for your travel-related app to also act like an art/museum exhibition, so anyone can enjoy an interesting tour of a given location.

Use the metaphors you think of to improve your design/product. E.g., you create a captivating app which virtual tourists can enjoy with (e.g.) virtual reality features.

SCAMPER – To help generate ideas for new solutions, ask 7 different types of questions to help understand how you might innovate and improve existing products, services, concepts, etc. SCAMPER is remarkably easy to learn and efficient in ideation sessions.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Six Thinking Hats – To reach for alternative viewpoints, you examine problems from 6 perspectives, one at a time (e.g., white hat = focusing on available data; black hat = focusing on potentially negative outcomes).

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Overall, it’s important to stay aware of where ideation sessions are going. You may need to pause to redirect the group’s thinking or introduce a new trigger/provocation to help the creative process. Later, you use convergent thinking to isolate optimal solutions.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Take our Creativity course, featuring lateral thinking.

This thought-provoking Smashing Magazine blog explores lateral thinking with more techniques.

Read one design team’s insightful account about lateral thinking.

The four lateral thinking techniques are:

Provocation: This involves disrupting conventional thinking patterns with unusual ideas.

Challenge: The challenge is about questioning the status quo. It’s about looking at things as if they might be wrong, even if they seem right. This approach encourages deeper analysis and alternative viewpoints.

Random entry: This technique generates new ideas using a random word or idea as a starting point. It creates connections that may not be immediately noticeable.

Alternatives: It focuses on shifting thinking patterns by exploring various directions and possibilities.

All these techniques encourage thinking outside the box and fostering creativity.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix discusses lateral thinking:

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

Lateral thinking and linear thinking are two distinct approaches to problem-solving. Linear thinking is sequential and logical. It follows a straight, step-by-step path that relies on data and analysis. It focuses on following the standard path of reasoning going along, as Alan Dix describes it.

Lateral thinking is non-linear. It involves creativity and looking at problems from various angles. It’s about challenging assumptions and exploring unconventional solutions.

Linear thinking concentrates on details and processes. Whereas lateral thinking emphasizes brainstorming and producing innovative ideas. Both are valuable, but they approach problems from different perspectives.

Watch as Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix discusses linear thinking:

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

Yes, lateral thinking is a valuable skill. It's a problem-solving approach that stresses creative thinking. Unlike traditional linear thinking, it's about exploring diverse ideas. You can hone this skill through practice, challenging assumptions, making unexpected connections, and approaching problems from fresh angles.

People skilled in lateral thinking are often adept at generating innovative solutions. Many fields, especially those requiring innovation and creativity, value this skill.

Watch as Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix discusses lateral thinking:

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

Lateral thinking often aligns with intelligence distinct from traditional measures like IQ. Intelligence manifests in various forms, and lateral thinking showcases creative, problem-solving intelligence. Lateral thinkers view things from unique perspectives. They create innovative ideas and link unrelated concepts. This ability marks an essential aspect of creative intelligence.

This video discusses problem redefinition and negotiation in real-world scenarios. Traditional intelligence focuses on finding a single right solution using given information. But lateral thinking is like solving real-world problems. This approach holds significant value in fields that demand innovation and creative problem-solving.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix discusses lateral thinking:

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

While different from traditional logical thinking, lateral thinking has its logic. It’s not illogical or random. Instead, it follows a distinct reasoning that prioritizes creativity and innovation. Traditional logic is linear and sequential. It focuses on reaching conclusions based on existing knowledge and facts.

Lateral thinking involves looking at problems from new angles and making unexpected connections. Lateral thinking is a creative way of problem-solving. It can help you find unique and practical solutions. Lateral thinking is a powerful tool when conventional logic doesn't work.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains different types of creativity and what can get in the way of being creative.

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

Lateral thinking and brainstorming are similar yet different. Lateral thinking helps solve problems using creative and unconventional approaches. It breaks away from traditional methods.

Brainstorming is a group activity where people contribute ideas without judgment to solve a problem. It generates creative solutions.

Lateral thinking can be a solitary or group activity and it focuses on thinking differently. It's a specific approach to problem-solving that emphasizes creativity.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix discusses lateral thinking:

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

Lateral thinking is crucial because it fosters creativity and innovation. It allows you to explore new ideas and solutions that conventional, linear thinking might not reveal. Lateral thinking helps adapt to new challenges and situations. It encourages looking at problems from multiple perspectives. This leads to more comprehensive and sometimes unexpected solutions. This type of thinking is crucial in innovative fields like business, technology, and design.

Lateral thinking breaks from traditional thought patterns and contributes to advancements and breakthroughs. It enhances problem-solving skills and promotes a more dynamic approach to challenges.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix discusses lateral thinking:

Enjoy our Master Class Harness Your Creativity to Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author, and Creativity Expert.

Yes, lateral thinking is a form of divergent thinking. Divergent thinking is about spontaneously generating diverse ideas or solutions to a problem. Lateral thinking, a term coined by Edward de Bono, is a specific kind of divergent thinking. It looks at problems from new and unusual angles and seeks innovative solutions outside conventions.

Divergent thinking is a broader concept encompassing various methods of generating creative ideas. Lateral thinking focuses more on breaking conventional patterns and thinking beyond the norm. Both are key in creative processes, encouraging broad exploration of possibilities.

Watch as Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains some helpful methods for thinking divergently—to get as many fresh ideas as possible and from many angles of a problem:

Enjoy our Master Class Harness Your Creativity to Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author, and Creativity Expert.

You can take the creativity course featuring lateral thinking to learn more about lateral thinking. This course would be a more in-depth and interactive way to learn. The course will also help develop your lateral thinking skills through practical applications.

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

de Bono, E. (1970). Lateral Thinking: Creativity Step by Step. Harper & Row.

Edward de Bono's Lateral Thinking introduces the concept of moving beyond linear, logical thought processes to embrace more creative and indirect approaches to problem-solving. De Bono provides techniques for generating innovative ideas by challenging established patterns and encouraging the exploration of alternative solutions. This seminal work has been instrumental in shifting perspectives on creativity, emphasizing the importance of thinking outside conventional boundaries to achieve breakthroughs in various fields.

Lateral thinking is changing your approach to solve problems or generate new ideas. Take Edward de Bono’s “Six Thinking Hats” as an example of lateral thinking. It involves adopting different roles to approach problems.

Watch as Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains “Six Thinking Hats”:

Imagine a person who is generally optimistic. Using the “black hat” approach, they could try looking at things negatively. This might help them find new, innovative solutions that they wouldn't have thought of. They can gain a better understanding of the situation by changing their perspective.

Take our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Lateral Thinking by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Lateral Thinking with our course Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your experts for this course:

Don Norman: Father of User Experience (UX) Design, author of the legendary book “The Design of Everyday Things,” and co-founder of the Nielsen Norman Group.

Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

Mike Rohde: Experience and Interface Designer, author of the bestselling “The Sketchnote Handbook.”

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!