What is Design Thinking and Why Is It So Popular?

- 1.6k shares

- 1 mth ago

Outside-the-box thinking is an ideation form where designers freely discard common problem-solving methods to find the true nature of users’ problems, falsify old assumptions and be innovative. Vital to the design thinking process, out-of-the-box thinking means reframing problems with a wider grasp of the design space.

“Thinking outside of the box allows you to get rewards outside of your reach.”

— Matshona Dhliwayo, Philosopher, entrepreneur & author

See where—and what—thinking outside the box can get you:

You've probably all heard that phrase 'thinking out of the box'. Everyone tells you, 'Think out of the box.' And it sounds so easy, and yet it's so difficult. If we're talking about theory and creativity, then we've got to think about *de Bono and lateral thinking*. So, if you're thinking out of the box, then lateral thinking is almost, not quite but almost, the same thing in different words.

And this idea of doing things that are breaking the mold, that are not following a line obviously covers a lot of creativity techniques, but particularly lateral thinking, de Bono's lateral thinking. The idea there is you've got, wherever you are, you've got your problem; you've got your start point. *Linear thinking*, in de Bono's terms, is very much about trying to follow the standard path, going along. So, if you're doing mathematics, you might pull the standard techniques off the shelf.

If you're writing a poem, you might be thinking line by line and thinking how each line fits and rhymes with the one before – if you're doing rhyming poetry, that is. So, it's all about following the same path of reasoning going on and on. *Lateral thinking is about trying to expand.* So, instead of following the same path of reasoning, are there *different places to start*? You know – are there different ways of thinking from the way where you are?

So, it's about trying to expand your idea of where you are outwards. So, that might be thinking of different solution strategies, so it might be thinking of different ways to start. Crucially, though, if you want to see out of the box or get out of the box, you actually often need to *see the box*. If you're literally in a cardboard box, you know you're in it. But mental boxes – you don't actually know you're in them. It's not that there's a cardboard wall and you don't go beyond it.

It's more like a hall of mirrors, so you never realize there's anything outside at all. Sometimes, *unusual examples* can help you see that. And that's, again, part of the reason for the bad ideas method, like *random metaphors* – things that, as soon as you've got something that *isn't in the box*, even if it's not a very good thing, it helps you to realize because you say, 'Well, *why* isn't this a good solution? Why doesn't it *work* as a solution?'

And as you answer that question about why, what you're doing is you're *naming that cardboard wall*. And once you've named the cardboard wall and you know it's there, you can start to think of what might be outside of that box but perhaps is a better solution. If you think about some of the analytic method— combining those, those are about building a map of the territory, which is very much about naming the box, naming the walls, naming the boundaries, and by naming them, by seeing from a distance what is there,

being able to then think of alternative solutions that are completely different. So, both alternative solutions help you to see the territory, help you to see the box. Of course, by seeing the box, that gives you the potential to have alternative solutions and actually you can iterate back and forth between those and hopefully build a better understanding of what is there and what is constraining you. If you understand what's constraining you, then you can start to break those constraints.

Traditional approaches to problem-solving can distort design teams’ views of problems. The most innovative solutions—both in product design and service design—usually come from designers who dared to step off the path of linear thinking to ask “Why?”. Design problems are usually complex, with many hard-to-see factors at play between users, the diverse realities they face and solutions they would find most effective, helpful and desirable. To follow a vertical, linear train of thought when addressing these would likely soon cause some big obstacles. With outside-the-box thinking, you can challenge assumptions that would otherwise constrain you, therefore freeing you to sidestep the dangers of meeting a design problem head-on.

Thinking outside the box can save you and your team the headaches of pursuing a perceived problem and ending up developing uninventive, semi-effectual solutions. So, instead of chasing shadows, you can work your way around the boundaries and explore the bigger picture. Moreover, it's a great way to discover other resources that might be available to you, spot market gaps and, indeed, inspire your design team in the ideation stage of any project. That’s why thinking out of the box is synonymous with, and integral to design thinking.

“The box” is the apparent constraints of the design space and our restrictions in perspective from habitually meeting problems as everyday “if x, then do y to get z” tasks. That clinical, critical line of reasoning we’re used to outside the design space will easily impose its limitations in design ideation. You can’t get a holistic view of the problem unless you start to explore horizontally and find its edges. To get outside the box, it’s important to:

Focus on overlooked aspects of a situation/problem.

Challenge assumptions – about any aspect of the problem or users.

Seek alternatives – not just alternative potential solutions, but alternative ways of thinking about problems.

© Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

Lateral thinking and divergent thinking methods can lead to the best results. Early in the ideation stage is the time to get disruptive and reconnect with a similar sense of wonder to how children challenge the norms which adults grow to accept without question. A persistence with “Why?” is the key, as is a judgement-free atmosphere in your ideation session. You want to ask significant questions that may seem outlandish – the idea being to scrutinize the assumptions everyone else would go along with because they’re “the done thing” and see if they’re actually valid.

Essentially, you want to reframe the problem and:

Understand what’s constraining you and why.

Find new strategies to solutions and places/angles to start exploring.

Find the apparent edges of your design space and push beyond them – to reveal the bigger picture.

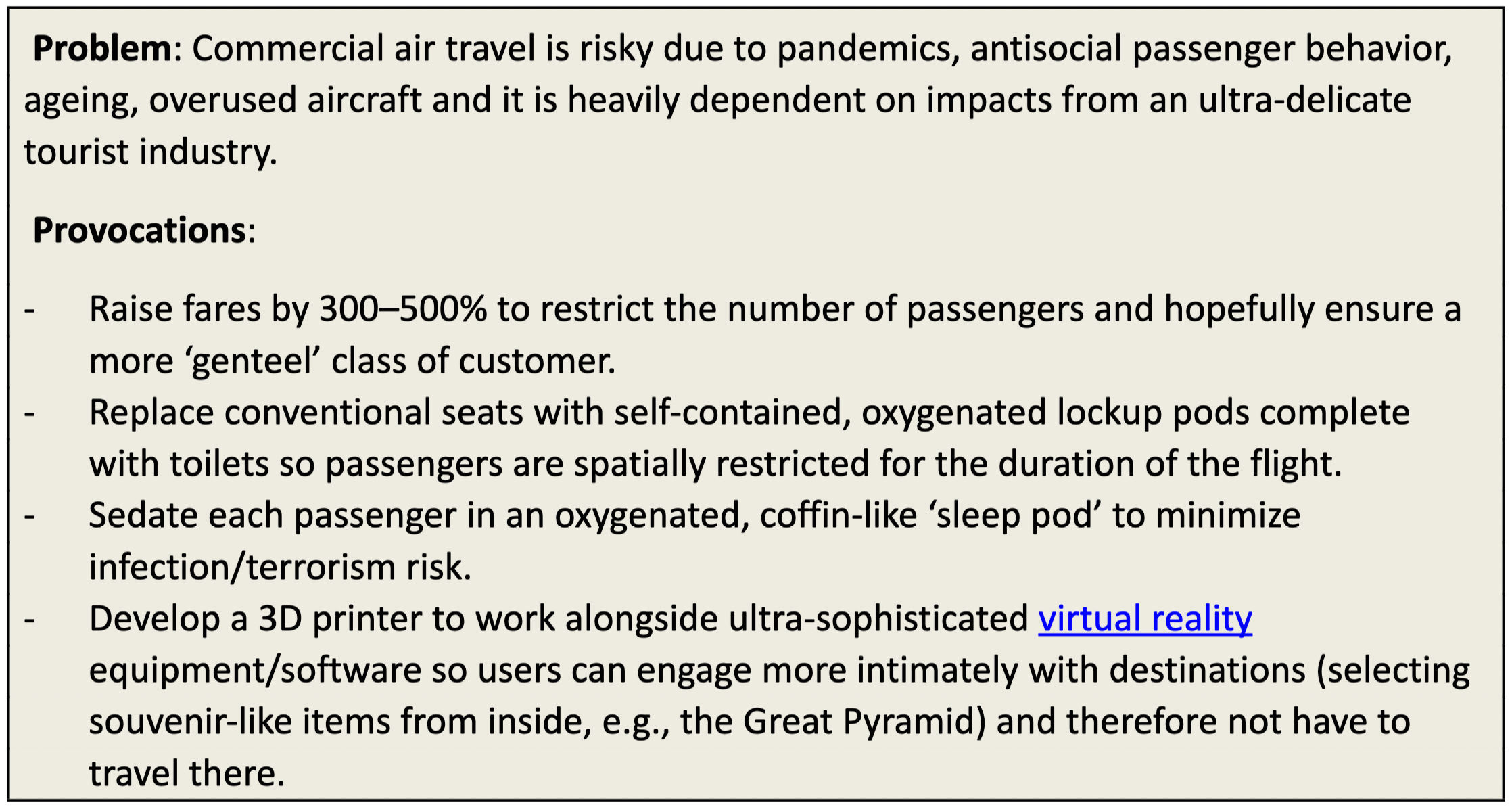

Of the various methods you can use, a chief one is provocations, where you make deliberately false statements about an aspect of the problem/situation. This could be to question the norms through contradiction, distortion, reversal (i.e., of assumptions), wishful thinking or escapism, for example:

Here, we see some norms of conventional air travel challenged and some unpredictable (and even socially unacceptable) notions to trigger our thinking. Our example showcases this method:

Bad Ideas – You think up as many bad or crazy ideas as possible, but these might have potentially good aspects (e.g., having self-contained compartments with toilets for passengers traveling together). You also establish why bad aspects are bad (e.g., raising prices so exorbitantly would A) foster social exclusion and B) not guarantee safety, anyway).

Design thinking is ideal for outside-the-box thinking, especially since its fluidity as a process lets you iteratively research, ideate, prototype and more as you fine-tune your way to the best solution. Ultimately, you should be able to investigate your problem—including factors affecting it—and harvest insights from its many dimensions by brainstorming or other means. From there, you use convergent thinking to zero in on the best solutions.

© Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

Take our Creativity course, featuring outside-the-box thinking.

Read how one design team leveraged outside-the-box thinking to great effect.

Grammarly’s blog succinctly captures the idea.

This video aptly answers the question of how to think outside the box.

You've probably all heard that phrase 'thinking out of the box'. Everyone tells you, 'Think out of the box.' And it sounds so easy, and yet it's so difficult. If we're talking about theory and creativity, then we've got to think about *de Bono and lateral thinking*. So, if you're thinking out of the box, then lateral thinking is almost, not quite but almost, the same thing in different words.

And this idea of doing things that are breaking the mold, that are not following a line obviously covers a lot of creativity techniques, but particularly lateral thinking, de Bono's lateral thinking. The idea there is you've got, wherever you are, you've got your problem; you've got your start point. *Linear thinking*, in de Bono's terms, is very much about trying to follow the standard path, going along. So, if you're doing mathematics, you might pull the standard techniques off the shelf.

If you're writing a poem, you might be thinking line by line and thinking how each line fits and rhymes with the one before – if you're doing rhyming poetry, that is. So, it's all about following the same path of reasoning going on and on. *Lateral thinking is about trying to expand.* So, instead of following the same path of reasoning, are there *different places to start*? You know – are there different ways of thinking from the way where you are?

So, it's about trying to expand your idea of where you are outwards. So, that might be thinking of different solution strategies, so it might be thinking of different ways to start. Crucially, though, if you want to see out of the box or get out of the box, you actually often need to *see the box*. If you're literally in a cardboard box, you know you're in it. But mental boxes – you don't actually know you're in them. It's not that there's a cardboard wall and you don't go beyond it.

It's more like a hall of mirrors, so you never realize there's anything outside at all. Sometimes, *unusual examples* can help you see that. And that's, again, part of the reason for the bad ideas method, like *random metaphors* – things that, as soon as you've got something that *isn't in the box*, even if it's not a very good thing, it helps you to realize because you say, 'Well, *why* isn't this a good solution? Why doesn't it *work* as a solution?'

And as you answer that question about why, what you're doing is you're *naming that cardboard wall*. And once you've named the cardboard wall and you know it's there, you can start to think of what might be outside of that box but perhaps is a better solution. If you think about some of the analytic method— combining those, those are about building a map of the territory, which is very much about naming the box, naming the walls, naming the boundaries, and by naming them, by seeing from a distance what is there,

being able to then think of alternative solutions that are completely different. So, both alternative solutions help you to see the territory, help you to see the box. Of course, by seeing the box, that gives you the potential to have alternative solutions and actually you can iterate back and forth between those and hopefully build a better understanding of what is there and what is constraining you. If you understand what's constraining you, then you can start to break those constraints.

Thinking outside the box means thinking freely and creatively—off the beaten path. It encourages a departure from standard or predictable thinking. It implies adopting unconventional and innovative approaches to problem-solving. Here is what you can do to get started:

Dive into the corners others might miss. Look beyond the obvious and focus on elements often overlooked in a situation.

Question the assumptions entrenched in the problem or regarding the users. Challenge the "given" and ask whether those assumptions are valid.

Don't settle for the expected. Seek not only solutions but also how to frame and approach the problem.

Yes, thinking outside the box is a valuable skill in problem-solving. It goes beyond regular solutions by exploring overlooked aspects, challenging norms, and looking past apparent boundaries. The skill involves questioning the usual ways of doing things and finding innovative solutions. The essence lies in addressing the edges and pushing beyond them to develop a dynamic and creative mindset.

Thinking outside the box involves lateral and divergent thinking methods.

During the ideation stage, be disruptive, persistently ask "Why?" and create a judgment-free atmosphere.

Reframe the problem by understanding constraints, finding new strategies, exploring different angles, and pushing beyond apparent boundaries to reveal the bigger picture.

Use provocations, such as deliberately false statements, to question norms and challenge assumptions.

Here are a few innovative ideas from the home to the workplace:

At Home - Imagine you have a small, unused space under your staircase at home. Comfortable seating, soft lighting, and bookshelves can turn an overlooked area into an inviting space. It demonstrates a creative use of space beyond its "supposed" purpose.

At Work - A common challenge in an eCommerce app is a high rate of product returns. It mainly happens because customers need more certainty about how items will look on them. So, you incorporate augmented reality (AR) for virtual product try-ons to enhance user satisfaction.

Creativity in thinking outside the box means introducing fresh and different ideas and breaking away from the norm. It is like analyzing other paths. The process involves exploring alternative options, questioning the "done thing," and finding clever solutions to problems. This video on Edward de Bono's "thinking hats" framework shows the connection between creative thinking and outside-the-box thinking. The "thinking hats" framework disrupts routine thinking, sparks creativity, and helps find new ideas and answers that change how to tackle challenges.

Let's now talk a little bit about roles in creativity, taking on a role. We'll start off by looking at de Bono again and the thinking hats. So, I think the two things if you've heard of de Bono will be lateral thinking and thinking hats. So, de Bono talks about *six hats*. One of the hats, what he calls the *white hat* is the information-seeking hat.

I think the white is supposed to be like the blank slate, blank piece of paper you write on. So, you're seeking information – you're finding out about things that are similar and related, and doing that kind of thing; it's a gathering stage. Then there's the *yellow hat*, which is the positive, bright, looking for the pros in everything, as opposed to the *black hat*, where you look at all the negative things, all the cons, all the reasons why something is bad. So, with those positive and negative, again – with the bad ideas, recall deliberately how do you think about what are the positive things about this idea?

What are the bad things about this idea? And then actually, once you've thought of the good things to critique those; so, alternating you between taking this sort of positive, active role of thinking what are good things, and taking the negative role. Then there's this *red hat*, which is about listening to your feelings, trying to get that gut reaction to something, getting that out without necessarily thinking about why you think that, just getting it out there. You can use some of these others to question it. The *green hat*, which is all about bright ideas,

thinking of just lots and lots and lots of ideas. And then, finally, and possibly most important the *blue hat* – the role management hat, actually looking back and saying, 'Have I actually thought about all of the (inaud.)? Have I spent time thinking about the positive aspects of this? Have I spent time listening to what I feel about this?' Actually, I'm going to pop back to that feeling one because I've – one of the techniques that I often suggest people use when they do qualitative research is

to deliberately do things that incite those gut feelings. So, what I suggest doing is if they've got some sort of model, some sort of vocabulary, is to look back to the original data to use their model to describe their data or use their vocabulary to describe their data. Perhaps it's something that somebody said, something that somebody did, and then say, 'it's just a...' – you know – so, 'it's just a...'

and then the words will be vocabulary. And see how much that rankles inside. So, effectively what you can do is create situations. And this is the role management thing; it's saying, 'Can I create a situation where I can apply the red hat, where I can generate feelings?' So, I think it's a quite useful set of – they're not the only things you could have. And there are different roles you can have; you might have roles which are perhaps more to do with – should we say – customer-focus or client-focus roles.

You know – so, one of you might say, 'I'm going to be thinking about – I'm going to be the problem owner.' And another person might decide to act as the technology provider, another person as perhaps the management role, and then think about each, taking that viewpoint to look at a problem. So, there are different ways you might choose roles. So, why are roles useful – taking a role on at times? Sometimes it's to help you *notice that you've neglected something*.

So, for instance, I mentioned the feeling one or it might be that you spent so much time thinking about positive things, you've not actually considered some of the negative features. So, by thinking about the roles, by putting a role hat on, you force yourself to think about things from *different viewpoints* and to not neglect some aspect. Particularly on that positive and negative hat, if you say, 'I am going to be the devil's advocate for a period,'

by stating that, by saying 'I am putting that hat on, I am taking that role on,' it can avoid a level of rancor in groups. So, if you're doing a group, if you're working together and somebody's being the proponent's idea, if you start saying negative things about it, everybody gets upset. If you say, 'Not because I think it's a bad idea, but because I'm going to take this negative role, I'm going to try and think of all the negative aspects about it,' it can make it a little bit easier. I mean, they still might hate you if you do it. So, it's a good idea to rotate the negative hat around. Everyone will love you while you're taking

the positive hat on; they'll hate you when you have the negative hat on, but by *knowing* it's a hat, it can help allow you to be – particularly in this critical role – without causing ill will. It might also help you to *go beyond your norms of behavior*. So, if you tend to be the sort of person who always sees the negative aspect, then actually deliberately taking the positive role, or vice versa, if you're the person who just, particularly if you don't like hurting people's feelings,

you might tend to encourage people. Think of all the positive things, think of things that help them, but actually sometimes it's *more* helpful to be critical, and so actually saying, 'Okay, just for a moment, I'm going to take that devil's advocate role, take that negative role and see where that leads me.' And it can help you to escape the patternings that you have. And particularly we mentioned the stepping back, the way that roles, actually thinking

'I am taking on a role' helps you think about the role. It makes you think that there are different roles you can take and that they can apply. So... thinking about roles helps you to step back from the problem, step back from you as a solution (inaud.)— whether it's a team or it's you as an individual, you might alternate roles yourself within a project; you might choose to take roles if you're working as a group. But that stepping back is quite an important bit and *seeing that it's a role* and therefore helping you to adopt them.

And they really make a difference. Taking on roles helps you think in *different* ways. So, this is seen particularly in work on gender studies and also work on issues to do with racial bias in things like job markets and examinations and things like that. And this is partly about the bias – we talked about bias earlier – but also about the way in which you tell stories to yourself. So, I come from a working-class background.

So, one of the stories I might tell myself if I'm not careful is – you know – 'Working-class boys don't do this' – as a child going to university or whatever it was. And I went to Cambridge University. You know – 'Working-class boys don't go to Cambridge University. Posh kids go there, not working-class boys.' We tell ourselves stories. What you find is when you do experiments and you get people to think just before an examination or a test about different kinds of roles

– now, that might be gender-reversal roles, it might be trying to think – of boys to think about more female things and vice versa. It might be about social background, a variety of things. You find it actually makes a substantial difference in the test scores. So, by just having people *think about different roles*, they suddenly *behave differently* because it's so easy to get trapped in the expectations we have of ourselves

built up individually over time; sometimes it's about our social situation. This also works for creativity. So, if you ask people to think about things that, shall we say, are creative things (inaud.), and it might be you spend time thinking about Einstein or DeRidder or Picasso, as opposed to, say, thinking about a foot soldier who's ordered what to do all the time or somebody who's sleeping – you know. So, if you think about creative things and then go into a creative situation,

that can actually help you be more creative. Throughout these videos, I constantly emphasize that we're all individual and different, and one of the most powerful things you could do is understand the way you are and then use it. But part of that is also – it's a bit like seeing outside the box – by understanding that, sometimes you can create these things and roles, and building these roles

for yourself is one of the mechanisms that allows you to for a period, for a purpose to actually reinvent yourself so that when you're addressing a particular problem sometimes you can literally address it as a different person.

An open and dynamic perspective provides a continuous flow of imaginative thinking. Creativity and outside-the-box thinking are about going beyond regular thinking to find possibilities. It paves the way for smart solutions and makes problem-solving more interesting.

Thinking outside the box is closely tied to critical thinking. While critical thinking is a part of the process, thinking outside the box goes a step further.

Critical thinking involves analyzing, evaluating, and reasoning through information to make judgments. It encourages exploring alternative perspectives and solutions.

Thinking outside the box focuses more on creative problem-solving and challenging assumptions. It involves questioning assumptions, challenging traditional norms, and reframing problems with a broader understanding.

Thinking outside the box shares similarities with critical thinking but is not synonymous. So, while complementing each other, they represent distinct aspects of cognitive processes.

Thinking outside the box is a positive and valuable approach. It is about looking at things differently, not just sticking to the usual ideas. Such techniques make problem-solving more exciting and compelling.

While the initial introduction of unconventional ideas might seem impractical or risky, the long-term benefits are substantial. This approach has the potential to handle creative blocks, lead to breakthroughs, and overcome limitations imposed by traditional thinking.

You can sign up for our comprehensive course 'Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services, to learn more about outside-the-box thinking. It equips you with skills and step-by-step methods to enhance your ability to generate innovative and valuable solutions. You will gain practical insights and tools to foster creativity in various workflows, programming algorithms, and professional settings.

Learn about hands-on ideation methods.

Explore more about divergent and convergent thinking in this video:

What I want to do now is talk about a few other kinds of divergent techniques. Creativity has two sides to it. There's being *novel* and being *useful*. There's a *divergent* side that's having lots and lots of bright ideas and a *convergent* side that tries to turn those ideas into something that's more useful and buildable.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Outside the Box Thinking by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Outside the Box Thinking with our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services .

The overall goal of this course is to help you design better products, services and experiences by helping you and your team develop innovative and useful solutions. You’ll learn a human-focused, creative design process.

We’re going to show you what creativity is as well as a wealth of ideation methods―both for generating new ideas and for developing your ideas further. You’ll learn skills and step-by-step methods you can use throughout the entire creative process. We’ll supply you with lots of templates and guides so by the end of the course you’ll have lots of hands-on methods you can use for your and your team’s ideation sessions. You’re also going to learn how to plan and time-manage a creative process effectively.

Most of us need to be creative in our work regardless of if we design user interfaces, write content for a website, work out appropriate workflows for an organization or program new algorithms for system backend. However, we all get those times when the creative step, which we so desperately need, simply does not come. That can seem scary—but trust us when we say that anyone can learn how to be creative on demand. This course will teach you ways to break the impasse of the empty page. We'll teach you methods which will help you find novel and useful solutions to a particular problem, be it in interaction design, graphics, code or something completely different. It’s not a magic creativity machine, but when you learn to put yourself in this creative mental state, new and exciting things will happen.

In the “Build Your Portfolio: Ideation Project”, you’ll find a series of practical exercises which together form a complete ideation project so you can get your hands dirty right away. If you want to complete these optional exercises, you will get hands-on experience with the methods you learn and in the process you’ll create a case study for your portfolio which you can show your future employer or freelance customers.

Your instructor is Alan Dix. He’s a creativity expert, professor and co-author of the most popular and impactful textbook in the field of Human-Computer Interaction. Alan has worked with creativity for the last 30+ years, and he’ll teach you his favorite techniques as well as show you how to make room for creativity in your everyday work and life.

You earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you’ve completed the course. You can highlight it on your resume, your LinkedIn profile or your website.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!