Introduction to the Essential Ideation Techniques which are the Heart of Design Thinking

- 1.2k shares

- 5 years ago

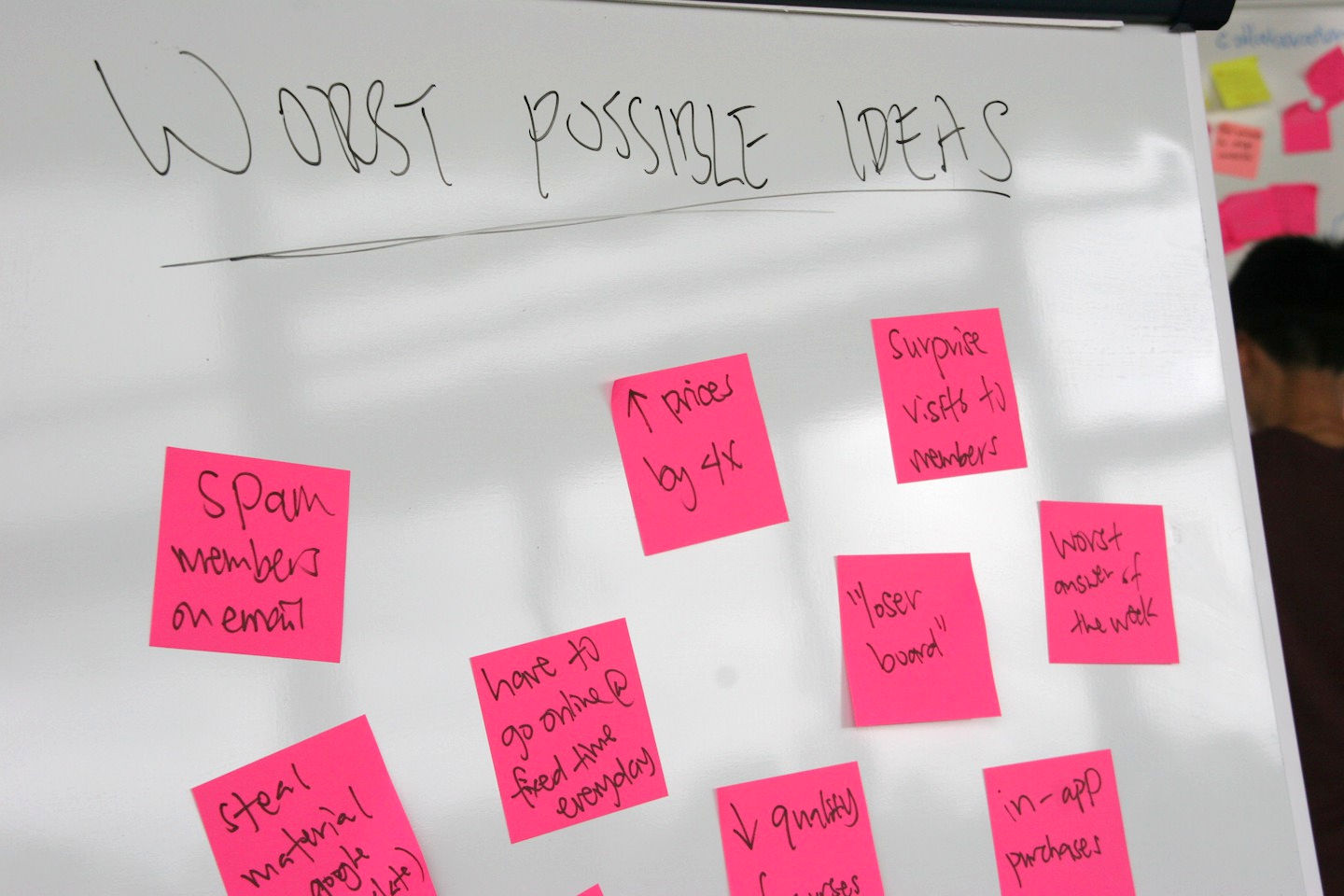

Worst Possible Idea is an ideation method where team members purposefully seek the worst solutions in ideation sessions. The “inverted” search process relaxes them, boosts their confidence and stokes their creativity so they can examine these ideas, challenge their assumptions and gain insights towards great ideas.

See how seeds of wisdom grow from even the most “toxic” soil.

Some people clam up in group sessions such as brainstorming, although everyone in a design team technically should feel free to explore all possibilities on the road to the best solution. With their peers surrounding them, they may be reluctant to offer input, fearing their ideas will make them look silly or short-sighted. Team members may also hold back on mentioning—and then forget—fragments or beginnings of plans that are actually valuable, fearing someone will rip their embryonic brainchild apart and humiliate them. When your design team uses the Worst Possible Idea technique, you avoid this by flipping the playing field. The name of the game is to produce the silliest, craziest ideas. Therefore, as nobody can look silly, nobody will worry about losing face. Better still, because the premise of the approach seems ridiculous, the group’s laughter relaxes us further as we proceed.

Author, president and co-founder of The Growth Engine Company LLC, Bryan Mattimore coined the term “worst possible idea” when he described turning the search for innovative ideas with a group of professionals upside down. The point was to kick-start a fruitful process for thinking up ideas by breaking with convention. Instead of getting stuck on trying for good ideas the group was encouraged to adopt a radically different approach. Soon, because everyone was searching for downright awful ideas, they could loosen up. And because the group could relax enough, they managed to overcome the impasse or mental constipation which the pressure of other ideation techniques can impose. In the case of the individuals Mattimore worked with, as they generated many seemingly terrible ideas, they found they could get on track towards what actually would work.

The real power of Worst Possible Idea is what happens after we start to feel more at ease about offering our thoughts. Although you and your team are free to kick back and try for the most ludicrous-sounding notions, there is a method to the madness.

To practice Worst Possible Idea, as group members we should:

Come up with as many bad ideas as we can.

List all the properties of those terrible ideas.

List what makes the worst of these so very bad.

Search for the opposite of the worst attribute.

Consider substituting something else in for the worst attribute.

Mix and match various awful ideas to see what happens.

When design team members identify a rotten-looking or “preposterous” idea and deconstruct it to see what makes it tick as such, they can find powerful insights that may serve as foundations for good plans elsewhere.

“Bad ideas started flowing. "Here's a really bad idea," said one banker. "We could round down everyone's deposits to the nearest dollar. Most people probably wouldn't notice." Said another, "let's make mistakes in their favor, give everyone extra money every time they make a transaction. Now that's a bad idea!" More laughter," but if you've ever seen the Bank of America "keep the change" savings program, perhaps it began in this session.”

— Bob Dorf, Co-author of The Startup Owner’s Manual (writing about Bryan Mattimore)

Find details on Worst Possible Idea and other Design Thinking techniques in the Interaction Design Foundation’s course.

Read Bob Dorf’s piece that sheds light on how Bryan Mattimore wielded Worst Possible Idea with powerful results.

Psychology author Drake Baer examines the dynamic of shame-culture in ideation sessions, offering some valuable and amusing insights.

UX (user experience) designers use the “Worst Possible Idea” technique instead of traditional brainstorming because it removes fear of failure and encourages unconventional thinking. Traditional brainstorming can lead to self-censorship, as participants may worry about proposing ideas that seem impractical, silly, or “wrong.” Team members may stay silent due to performance anxiety or a fear of being judged. This technique offers an “antidote” to that fear, and it flips the script—so, the sillier or more “wrong,” the better the idea! Designers intentionally come up with the worst ideas possible, making the process more fun and relaxed.

There’s a method to the “madness.” By focusing on terrible ideas, teams expose hidden assumptions and discover unexpected solutions. Once the worst ideas are on the table, team members can reverse or refine them into viable concepts. For example, if a “worst idea” for a navigation system is “users must solve a puzzle to find the menu,” it might spark the thought of adding delightful micro-interactions instead.

This method works well in UX because it breaks creative blocks and allows designers to explore bold, innovative ideas that might not surface in a traditional brainstorming session.

Watch as Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains important points about bad ideas and why they’re good for design:

To run a “Worst Possible Idea” session, get your team together and clearly define the problem you’re trying to solve. Set a fun and relaxed tone—this technique works best when people feel free to be playful and creative and there’s no pressure to “succeed.”

Start by asking everyone to come up with the worst, most ridiculous, or completely unhelpful ideas related to the problem. Encourage ideas that would make the user experience frustrating, confusing, or even absurd. Write down every suggestion without judgment.

Once you’ve got a list of terrible ideas, analyze them. Ask the team, “What makes these ideas so bad?” and “Can we flip them into something useful?” Often, these bad ideas highlight real pain points or hidden assumptions.

Finally, take the most interesting bad ideas and reverse them into potential solutions. This method helps teams break out of conventional thinking and discover creative, unexpected UX improvements. They can escape from both the pressure of having to come up with “correct” ideas in a meeting and the constraints of assumptions they might not realize they had about the subject. Keep the energy light and fun—this is where innovation happens and “design fails” succeed (at least, in the beginning, for a purpose)!

Watch Professor Alan Dix explain how to get into bad ideas as an ideation method:

To turn bad ideas into useful ones, try these steps:

Set the problem – Clearly define what you’re trying to solve. Make sure that everyone understands the goal.

Generate bad ideas – Encourage the team to come up with the worst, most ridiculous ideas possible (the worse, the better!). Write everything down without judgment.

Analyze why they’re bad – Discuss what makes each idea terrible. Is it confusing? Annoying? Impractical? This step helps uncover real UX pain points.

Flip the bad into good – Look for elements that could work in reverse. For example, if a bad idea is “make users solve a puzzle to find the checkout button,” flipping it could lead to a more engaging checkout experience.

Refine and test – Take the best reversed ideas, refine them into practical solutions, and then test them with users.

This method pushes creativity and helps uncover unexpected, valuable design solutions. Good things really can grow from the most unlikely-looking, “terrible” soil!

Take our Master Class Harness Your Creativity to Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author and Creativity Expert.

A “Worst Possible Idea” session should last 30 to 60 minutes. It depends on the team size, complexity of the problem, and whether you include an icebreaker exercise (which is useful if some participants don’t know each other).

Start with 5-10 minutes to clearly define the problem. Then, give the team 10-15 minutes to generate the worst possible ideas—encourage weird, wild, wacky, absurd, and downright terrible suggestions without judgment. Next, spend 10-15 minutes analyzing why these ideas are so bad. This step helps uncover hidden assumptions and potential pain points to explore.

In the last 15-20 minutes, you should all focus on flipping bad ideas into useful ones. Look for patterns, reverse negative elements, and refine the most promising ideas into actionable solutions.

It’s a good idea to keep the session under an hour because it ensures high energy and avoids overthinking. If the team is engaged and generating strong ideas, a longer session might work, but the goal is quick creativity and fresh insights, not perfection. Keep the pace lively, and don’t let the process drag—innovation happens when energy stays high!

Watch Professor Alan Dix explain how to get into bad ideas as an ideation method:

A “Worst Possible Idea” exercise works best with four to eight people. This size keeps discussions lively while ensuring everyone has a chance to contribute.

With fewer than four people, the range of ideas may be too limited, and the session might feel less dynamic. On the other hand, more than eight people can make it harder to manage discussions, and some participants may hesitate to share their thoughts.

A balanced group should include a mix of roles—designers, developers, product managers, or even customer support reps. Different perspectives help uncover unique insights and challenge assumptions.

If the team is larger, consider breaking into smaller groups, each working on bad ideas separately before sharing with the whole team

Remember, the goal isn’t just to generate bad ideas—it’s to spark unexpected, useful solutions—so good moderation skills are helpful to make sure a session runs smoothly. A well-sized group encourages creativity, ensures engagement, and explores further in the ideation space without overwhelming the process.

Take our Master Class Harness Your Creativity to Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author and Creativity Expert.

The "Worst Possible Idea" method works best for UX problems that need fresh, creative thinking or when a team feels stuck. It’s especially useful for improving user flows, addressing engagement issues, reducing user frustration, overcoming innovation challenges, and rethinking assumptions. Assumptions especially have a bad “habit” of being too close to designers (and other people) for them to notice or challenge.

For example, if users struggle with onboarding, coming up with terrible ideas—like a 10-page sign-up form—helps reveal what to avoid and why. From there, the method sparks ideas among team members for a smoother experience

However, a “Worst Possible Idea” approach is not universally the best choice for every problem. It’s less effective for highly technical UX problems, like optimizing page load speeds or complex backend logic, where creative ideation isn’t as useful. So, while the method is powerful, its success depends on the type of problem and the team’s goals.

Take our Master Class Harness Your Creativity to Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author and Creativity Expert.

A great example of solving a real-world UX problem with the “Worst Possible Idea” technique comes from improving checkout flows in e-commerce. It’s a simple illustration but shows the principle at work—with terrible ideas turned upside down to form good design ideas.

Let’s say a team struggling with high cart abandonment rates used this method to rethink their process. First, they generated terrible checkout ideas, such as the following:

Forcing users to create an account before checkout

Hiding the checkout button in a hard-to-find place

Asking for excessive, unnecessary information

From analyzing why these ideas were bad, they uncovered key pain points: users hate forced sign-ups, confusing navigation, and long forms. Flipping these insights, they redesigned the checkout process to include the following:

A guest checkout option

A clear, prominent checkout button

Autofill and progress indicators to speed up the process

This approach helped them simplify the user flow, reduce friction, and increase conversions. The worst ideas exposed real usability issues, making it easier to design a smoother, more user-friendly experience.

Watch as Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains important points about bad ideas and why they’re good for design:

Yes, the “Worst Possible Idea” method can backfire if the team fails to flip bad ideas into useful insights. For example, if participants focus too much on the “terrible” aspect, they might end up joking or exaggerating. If they get distracted like that, they might not take the process seriously enough to extract real value.

Another risk is accidentally reinforcing bad design choices. If a team misinterprets a “bad” idea as innovative without validating it properly, they could introduce confusing or frustrating UX elements.

To avoid this, teams should analyze each bad idea carefully and always test refined solutions with real users. The method works best when it’s treated as a tool for breaking creative blocks, not as a direct roadmap for design.

So, while the method doesn’t inherently lead to negative design decisions, careless execution can result in misguided takeaways. That’s why critical thinking and user testing are essential to make the most of this helpful method to explore the idea space in a safe and thorough way. A good thing to remember might be: “The real worst idea is no idea.”—which means the worst thing that can happen is nobody thinks of anything.

Watch Professor Alan Dix explain how to get into bad ideas as an ideation method:

Mattimore, B. (2012). Idea Stormers: How to Lead and Inspire Creative Breakthroughs. Jossey-Bass.

Bryan Mattimore presents a range of creative ideation techniques, including the "Worst Possible Idea" method, which challenges teams to generate deliberately bad ideas as a way to spark fresh perspectives. This book is essential for anyone leading brainstorming sessions or seeking innovative solutions.

It can go either way. The "Worst Possible Idea" method is typically done as a group activity, but individual preparation for a brainstorming session can sometimes be more effective.

By sharing bad ideas out loud in real time, participants can build off each other’s absurd suggestions—and it makes the process more dynamic and spontaneous. The goal is to create a playful, low-pressure environment where bad ideas spark discussion and unexpected insights.

Do you work on your own at all, then? Yes—your own bad ideas will come from your own mind! It’s just that the best results usually come when the team works together from the start, so share your “terrible” ideas right away. This mix of solo and group work keeps creativity high while benefiting from diverse perspectives. It also ensures introverts and extroverts both have a voice in the process.

Watch as Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains important points about bad ideas and why they’re good for design:

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Worst Possible Idea by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Worst Possible Idea with our course Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your experts for this course:

Don Norman: Father of User Experience (UX) Design, author of the legendary book “The Design of Everyday Things,” and co-founder of the Nielsen Norman Group.

Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

Mike Rohde: Experience and Interface Designer, author of the bestselling “The Sketchnote Handbook.”

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!