Ideation for Design - Preparing for the Design Race

- 865 shares

- 5 years ago

Mind maps are visual diagrams that structure information around a central idea, with linked ideas branching out. Designers use them to organize thoughts, analyze information and develop creative solutions. Mind maps give a clear structure and hierarchy of thoughts and make complex concepts easier to understand. They include a central idea, topics and subtopics showing as nodes, and branches connecting these nodes.

Mind maps are a helpful way to clearly flow out ideas and build on them.

© Nicoguaro. Copyright terms and licence: CC BY-SA 3.0

In user experience (UX) design, effective organization and a clear understanding of information are nothing short of vital for any digital product to succeed. Sure enough, designers and design teams depend on this clarity to help create user-friendly products and services. One powerful tool that designers can get working for them is a mind map. Psychology Author and Television Presenter Tony Buzan coined the term “mind mapping” in 1974 as a form of brainstorming. Mind maps—or spray diagrams or spider diagrams—give a visual representation of information. This makes it easier to navigate and comprehend complex concepts from a high level as well as in finer granularity.

Mind maps play a crucial role in UX design, project planning and many other areas—such as working with market research. They help designers organize their thoughts, analyze information and develop creative solutions from a big-picture vantage point. Such maps can also incorporate color coding and icons to help with comprehension and navigation. Here are some key reasons why these maps are important:

Mind maps are tools that empower designers to visually structure information and organize it in a clear way. When designers set out their ideas and concepts in a hierarchical style, they can easily achieve several things: They can find relationships, prioritize information and create logical flows within their designs. This improves the overall organization—as well as the clarity of the UX design process.

These maps stimulate creative thinking and problem-solving. That’s because they let designers get out and explore different possibilities and connections. When designers visually map out ideas, they can start building up new insights, identify patterns and uncover innovative solutions to the design challenges that are facing them. The visual nature of mind maps encourages out-of-the-box thinking—and it helps the design team generate creative ideas in their brainstorming sessions.

Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains thinking outside the box in this video:

The maps serve as effective communication tools. They enable designers to present complex information in a simple and visually appealing format that’s easy to understand for other team members—some of whom may not be as much of visual designers. These maps make it easier for design team members to collaborate more effectively—along with stakeholders and clients—since they give a shared understanding of design concepts and project goals. Mind maps are deliverables that are really easy for design teams to share, review and modify—ideal for a design process that’s truly collaborative and iterative.

Mind maps help designers gain a deeper understanding of the users' needs, goals and preferences. As designers organize user research findings and insights this way, they can identify user patterns, customer touchpoints, pain points and motivations. This understanding informs the design process early on—and long before usability tests of the mobile apps that teams might design, for example. It enables designers to create user-centered experiences in digital products and services that meet their users' expectations and goals.

These maps can work as a powerful aid in project management since they give a visual overview of the design process. Designers can use mind maps to plan and track project milestones, allocate resources and set their priorities. The visual representation of tasks and timelines like this helps streamline the project management process. This streamlining goes a long way to making sure of an efficient workflow and the timely delivery of design projects.

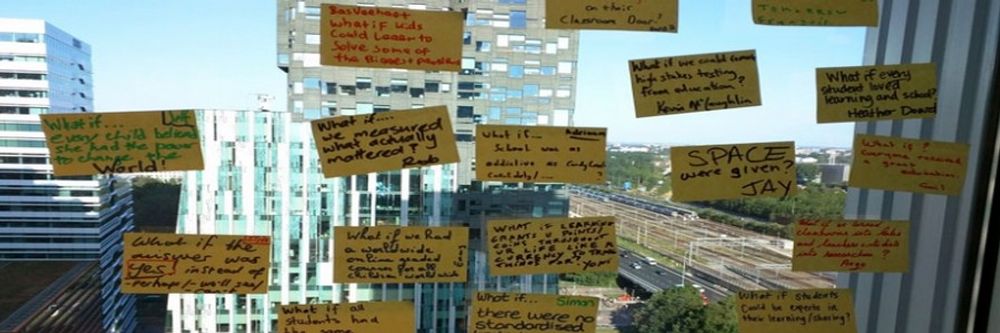

This mind map presents a big problem or main idea for a design team to address with questions.

© Magda Mihalache, Fair Use

Designers can employ mind maps at various stages of the design process to organize information, generate ideas and structure designs. Designers can follow this step-by-step process where they:

1. Define the central idea or main topic of the mind map. This should be a concise and clear statement that encapsulates the purpose or objective of the design project.

2. Identify key themes and subtopics related to the central idea. These can be broad categories or specific areas of focus within the design project.

3. Create nodes for each key theme or subtopic. These nodes will serve as the main branches that stem out from the central idea.

4. Add branches that connect each node to the central idea. These branches represent the relationships between the main topic and the subtopics.

5. Expand subtopics to make them more detailed. For each subtopic, designers further expand the map when they put in additional nodes and branches. These represent more specific ideas, concepts or features related to each subtopic.

6. Use color coding and icons to improve how visually clear the mind map is. Designers assign different colors to different themes or subtopics, and they use icons to represent specific ideas or concepts.

7. Review and refine the mind map to make sure that it accurately represents the information and relationships the designers want to show. They should refine the structure, wording and visual elements—as needed—to improve clarity and readability.

This mind map represents the workings of Netflix’s UI, as well as the flow involved when a user logs onto the app or website.

© EdrawMind, Fair Use

Designers can follow some best practices for mind mapping techniques, such as these:

Use concise and clear wording for nodes and branches. Avoid lengthy descriptions or complex language that may keep users from understanding properly.

Incorporate icons, symbols and images to boost the visual appeal of and how well people will understand the map. Visual elements can help carry information more effectively and engage viewers that much better.

Arrange nodes and branches in a logical and hierarchical order. Be sure to put the most important information in a position that’s prominent. Information that’s set out like this makes sure that the most crucial concepts and ideas are easy for team members and stakeholders to access and understand.

The map is there to develop; so, it’s vital to allow for flexibility and creativity in it. Encourage the exploration of different ideas and connections—even if they seem unconventional at first. These maps are a tool to help generate innovative solutions and think outside the box.

Mind maps aren’t static. The idea is that they evolve and adapt as the design process moves forward. Designers should continue to review, refine and update mind maps whenever new insights and ideas come to the surface.

Here—and in no particular order—are some of the best programs that UX designers commonly use:

1. MindMeister: a popular online mind mapping tool that offers a user-friendly interface and collaborative features. It allows for easy creation, editing and sharing of mind maps—making it suitable for team collaboration.

A MindMeister mind map diagrams a launch meeting.

© MindMeister, Fair Use

2. XMind: a versatile mind mapping software that offers a range of features. These include various templates, advanced brainstorming tools, as well as seamless integration with other productivity tools.

XMind supports diagram formats in addition to mind maps, such as logic charts, brace maps, org charts and tree charts.

© Built In, Fair Use

3. EdrawMind: a full-featured cross-platform tool for mind mapping, brainstorming, outlining and presentation.

This EdrawMind map displays branches.

© EdrawMind, Fair Use

4. Coggle: a web-based mind mapping tool that provides a simple and intuitive interface. It offers real-time collaboration, customizable themes and the ability to add images and links to mind maps.

A work-in-progress Coggle mind map; the quick-keys guide is open (right-hand side).

© Built In, Fair Use

5. Miro: a digital collaboration platform that offers a wide range of tools, including mind mapping. It provides a collaborative workspace where teams can create, edit and share mind maps in real-time.

This Miro mind map charts processes and sub-processes in Agile software development.

© Miro, Fair Use

6. Lucidchart: a cloud-based diagramming tool that includes mind mapping functionality. It offers a drag-and-drop interface, collaboration features and integrations with other popular tools.

This template from Lucidchart can help designers and teams grow and flow ideas.

© Lucidchart, Fair Use

It’s important for designers to consider several factors when they select a mind mapping software program. These include ease of use, collaboration features, customization options and integration capabilities with other tools that they use in their design process.

Such maps can take various forms and have uses in a multitude of contexts. Here are some examples used in UX design:

A mind map can visually represent the user's journey through a product or service. It can highlight key touchpoints, pain points and opportunities for improvement. User journey maps and customer journey maps are important UX deliverables in any case—so, it’s valuable to have this visualization in place early on.

CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers explains how to map a user journey for a service in this video:

A mind map can help organize information and define the structure of a website or application. It can show the hierarchy of pages and their relationships. As such, it can serve as a kind of foundation or wireframe for what the design team have got in mind.

A mind map is an excellent tool to brainstorm with and explore different design concepts. As it facilitates such levels of creativity, it frees a design team to generate and organize ideas for a new product or feature.

Watch our video on brainstorming for insights into this powerful group activity:

A mind map can help a design team plan and organize content for a website or application. It maps out the various sections, pages and content types—such as the best material for a landing page.

The versatility of mind maps lets designers adapt them to their specific design needs and objectives. In a similar way to how user personas help bring qualities and needs of a target audience to the surface for the design team to work with, mind maps help bring ideas to life for designers and developers and others associated with a project.

Remember the power of UX design mind maps as tools to foster collaboration regarding how to understand potential customers, feel out content ideas for ideal customers and users, identify types of content that best suit business goals—and much more. Mind mapping for design thinking is particularly effective, and it’s important to leverage mind map templates. With the right map, a team can drive innovation and help create user-centered design experiences and product designs that truly resonate with their target audience.

Take our course on Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide.

Consult our piece The Principles of Information Visualization for Basic Network Data.

Read Figma’s resource How to Mind Map for additional information.

Consult 20 Best Mind Mapping Software For Visual Collaboration In 2024 by Ben Aston for more insights.

Read A mind map for gaining clarity in UX research by Magda Mihalache for further details.

When designers create mind maps, they often run into several challenges. These tend to include information overload, organizing complex data and making sure that productive collaboration happens. So as to address information overload, designers prioritize data by focusing on the most critical user needs and design objectives. This approach helps in filtering out less relevant information and maintaining clarity within the mind map. To organize complex data effectively, designers use colors, symbols and branches so they can categorize and link related ideas. This visual differentiation helps to navigate the mind map—and highlights relationships between different concepts. For instance, to use distinct colors for different user groups or design elements can make the map easier to understand at a glance.

To make sure that fruitful collaboration among team members occurs can also pose a challenge, and that’s especially so in remote settings. Designers tackle this by using digital mind mapping tools that allow for real-time collaboration. These tools empower team members to contribute simultaneously, share insights and provide feedback—which ensures that the mind map does indeed reflect a collective understanding of the project.

See more about brainstorming in our video:

To start a mind map for a UX project, first, choose a central idea or concept related to the project. Write this idea at the center of a blank page or digital canvas. From there, draw branches that represent main categories or themes related to your central idea. These could be user needs, design elements or functionalities. For each main category, extend further branches to break down the categories into more specific aspects or tasks. Remember to keep your mind map clear and organized—use colors, icons or symbols to categorize or prioritize information. This visual organization helps you and others spot relationships between different elements of the project and nurtures creative solutions. Finally, make sure you review your mind map and update it as your project keeps evolving. This dynamic tool adapts to the changing needs and insights of your UX project. That makes it an invaluable resource for brainstorming, planning and communication among team members.

Take our Master Class Harness Your Creativity To Design Better Products with Author and Human-Computer Interactivity Expert, Professor Alan Dix.

Mind maps serve as powerful tools for understanding user needs in UX design. As mind maps visually organize thoughts and ideas, they let designers see connections and patterns that mightn’t be obvious at first glance. When you create a mind map, you start with the user at the center—and from there, branch out to different aspects of their experience, such as challenges, motivations and goals. This method highlights the hierarchy and relationship between different user needs—and so makes it easier to prioritize them in the design process.

What’s more, mind maps make collaboration easier among team members. They provide a clear and accessible overview of user needs. Plus, they make sure everyone understands the user perspective. This shared understanding helps with generating more targeted and creative solutions. Another point is that mind maps are adaptable. As new insights emerge from user research, you can easily update them, and so make sure the design process remains user-centered. Overall, mind maps are invaluable for distilling complex user data into a cohesive understanding—which guides the design process towards more intuitive and user-friendly solutions. So, they can serve as valuable deliverables within case studies where teams have worked their way towards winning design solutions.

Take our Master Class A Guide To Hassle-Free Designer-Developer Collaboration with Szymon Adamiak, Co-Founder, Hype4 Mobile.

In UX design, colors and images play crucial roles in enhancing mind maps. That makes them not just more visually appealing but more effective as tools for communication and idea organization, too. Colors help to categorize and prioritize information—letting designers quickly differentiate between various themes or concepts at a glance. For instance, if designers use a distinct color for each user need or design challenge, it makes it easier to identify and focus on specific areas of interest.

Images, on the other hand, serve as visual shorthand. They enable designers to represent ideas quickly and intuitively. They can symbolize complex concepts or emotions that might take longer to describe with words. So, they speed up the understanding and brainstorming process. What’s more, the use of images makes mind maps more memorable and engaging. That can be particularly useful in collaborative settings, and make sure that key insights stand out and that team members or stakeholders won’t overlook them.

Together, colors and images transform mind maps from simple outlines into dynamic, informative and inspiring visual tools. They make for deeper understanding and creativity; plus, they help UX designers to effectively explore and address user needs, while also nurturing a more collaborative and inclusive design process.

Arielle Eckstut, Author and Co-Founder of The Book Doctors and LittleMissMatched, and Joann Eckstut, Color Consultant and Founder - The Roomworks, explain color and its importance in this video:

Take our Master Class How To Use Color Theory To Enhance Your Design with Arielle Eckstut and Joann Eckstut.

To convert a mind map into a UX design prototype is something that takes a few structured steps. First, review your mind map to identify the main user needs and design concepts. These elements form the backbone of your prototype, and guide the layout and functionality.

Next, prioritize the features or ideas in your mind map based on user needs and project goals. This step helps you decide what to include in the initial prototype. Begin sketching wireframes or using digital tools to create basic layouts that represent your prioritized ideas. These wireframes serve as the visual blueprint for your prototype—and they show how users are going to interact with the design.

After you sketch, select a prototyping tool that suits your project needs. Transfer your wireframe sketches into the tool, refining them into interactive prototypes. At this stage, focus on usability and user flow rather than detailed aesthetics.

Finally, test your prototype with users so you can get and gather feedback. Use insights from this testing to refine your design—and iterate until it meets user needs effectively. This process turns the abstract ideas in your mind map into a tangible and user-centered design prototype, ready for further development.

Professor Alan Dix explains the importance of and need for prototyping in this video:

Mind maps greatly support the making of these since they give a visual framework to organize and analyze research data about potential users. When you start with a central concept—like a specific user group or project goal—you can branch out to include various characteristics of your target users. These branches can represent demographics, behaviors, needs, goals, frustrations and preferences.

As you add layers to the mind map, you categorize and connect different pieces of information. That helps you identify patterns and insights. This process makes it easier to see the common traits among potential users, and it guides you as you create detailed and accurate user personas. These personas then act as reference points for design decisions, and ensure that the product meets the real needs of its users.

Watch this video as UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains the significance of user personas in design:

Images

Copyright holder: Benoît Prieur. Appearance time: 10:32 - 10:36 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 4.0. Modified: No. Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Avenue_Berthelot-_machine_pour_entrer_dans_l%27h%C3%B4tel.jpg

Take our Master Class How To Create Actionable Personas with Daniel Rosenberg, UX Professor, Designer, Executive and Early Innovator in HCI.

To do this, start by defining a clear central theme or question. This theme acts as the anchor for all subsequent ideas, and it makes sure the mind map remains relevant to your project goals. Next, use branches to categorize information logically, and group related ideas together. This structure helps to maintain clarity and prevents the map from becoming cluttered.

To use colors and symbols is another highly effective strategy. Assign different colors to various categories or priorities—and so make the map visually organized and easier to navigate. Symbols can represent specific types of information or actions, a factor that adds another layer of organization.

To limit the amount of text on each branch is good as it encourages simplicity and focus. Instead of long descriptions, use keywords or short phrases that capture the essence of an idea. This approach keeps the mind map clean and accessible.

It’s crucial to regularly review and refine the mind map. As the project evolves, some ideas may become less relevant, while new insights come up. Update the mind map to reflect these changes, and also remove outdated information and add new findings. This practice ensures that the mind map remains a useful, focused tool throughout the design process.

Consult our piece The Principles of Information Visualization for Basic Network Data.

To present a mind map to stakeholders in a UX project is a task that takes a clear and structured approach. First, make sure that the mind map is visually appealing and easy to understand. Use colors, symbols and clear labels to organize information logically. This visual clarity helps stakeholders quickly grasp the main ideas and their connections. Start the presentation by explaining the central concept or goal of the mind map. Then, guide stakeholders through the main branches; highlight key insights, user needs and design considerations. Focus on how these elements relate to the project objectives and the decisions they inform. Be prepared to zoom in on specific details or branches as questions arise.

Stakeholders might be interested in particular aspects of the project—like user pain points or design solutions. When you’ve got a flexible presentation style it lets you address these interests directly. What’s more, emphasize how the mind map has made the design process easier. Share examples of how insights from the mind map have influenced design choices or strategies. This demonstrates the value of the mind mapping approach in driving user-centered design decisions. Finally, invite feedback and suggestions. To engage stakeholders in a dialogue about the mind map can provide valuable perspectives and foster collaboration. It’s an opportunity to refine your understanding of user needs and project goals based on stakeholder input.

Take our Master Class Win Clients, Pitches & Approval: Present Your Designs Effectively with Todd Zaki Warfel, Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach.

Mind maps help do this by providing a visual and intuitive way to capture complex information. When you use a mind map, you start with a central theme related to your research—such as a specific user behavior or project goal. From this central point, you branch out to include different categories of findings, like user needs, pain points and preferences. This branching structure helps you logically organize data. That makes it easier to see connections between different observations. For example, you can link user needs directly to design recommendations, and create a clear pathway from research insights to actionable solutions. Also, mind maps enable you to prioritize information.

When you use different colors or symbols, you can highlight key findings or urgent issues, and make sure that they stand out and receive appropriate attention during the design process. Mind maps are also great ways to make collaboration easier and more effective. By presenting research findings in a visual format, you make it accessible to team members who mightn’t be familiar with the details of the research. This shared understanding helps align the team’s efforts and supports a user-centered approach to design. Overall, mind maps transform the complexity of UX research findings into a structured, understandable and actionable format. This makes them an invaluable tool in the UX design process.

Watch as William Hudson explains user research and why it is so important in this video:

To incorporate user feedback into a UX design mind map is something that takes a few key steps to make sure that the design process remains user-centered. First, gather feedback from users through methods such as interviews, surveys or usability testing. This feedback should cover various aspects of the user experience, including usability, satisfaction and any difficulties users encountered.

Next, review the feedback to identify common themes, problems and suggestions. This analysis helps in understanding the user's perspective and the areas that require improvement or reevaluation.

Once you’ve identified these key insights, update your mind map to reflect this new information. You can add branches to represent user feedback—categorizing it by themes such as usability issues, feature requests or user satisfaction. Use colors or symbols to highlight feedback that needs immediate attention or has a deep impact on the user experience.

To work user feedback into the mind map doesn’t just help in visualizing the changes needed; it also makes sure that the design process adapts to meet user needs. To regularly update the mind map with new feedback is something that keeps the design team aligned with user expectations; plus, it improves the overall design outcome.

UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains about usability testing in this video:

Take our Master Class How to Get Started with Usability Testing Webinar with Cory Lebson, Principal and Owner of Lebsontech LLC.

1. Farrand, P., Hussain, F., & Hennessy, E. (2002). The efficacy of the 'mind map' study technique. Medical education, 36(5), 426-431.

This study was one of the first to empirically investigate the effectiveness of mind mapping as a study technique among medical students. The researchers found that mind mapping led to improved long-term factual recall compared to traditional note-taking methods. This study has been highly cited and has contributed to the growing body of evidence supporting the use of mind mapping in educational and professional settings.

2. Eppler, M. J. (2006). A comparison between concept maps, mind maps, conceptual diagrams, and visual metaphors as complementary tools for knowledge construction and sharing. Information visualization, 5(3), 202-210.

This paper provides a comprehensive analysis and comparison of various visual mapping techniques, including mind maps, concept maps and conceptual diagrams. It explores the unique characteristics, strengths and applications of each technique, highlighting their complementary nature in knowledge construction and sharing. This work has been influential in clarifying the distinctions and relationships between these visual tools, guiding researchers and practitioners in selecting the most appropriate technique for their needs.

Buzan, T., & Buzan, B. (1996). The Mind Map Book: How to use radiant thinking to maximize your brain's untapped potential. Plume.

This seminal work by Tony Buzan and Barry Buzan is considered the foundational text on mind mapping. It introduced the concept of radiant thinking and provided a comprehensive guide on how to create and use mind maps to enhance learning, creativity and problem-solving. The book has been highly influential in popularizing mind mapping as a powerful cognitive tool and has inspired numerous subsequent studies and applications in various fields.

Remember, the more you learn about design, the more you make yourself valuable.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

We've emailed your gift to name@email.com.

Improve your UX / UI Design skills and grow your career! Join IxDF now!

Here's the entire UX literature on Mind Maps by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Mind Maps with our course Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide .

Master complex skills effortlessly with proven best practices and toolkits directly from the world's top design experts. Meet your experts for this course:

Don Norman: Father of User Experience (UX) Design, author of the legendary book “The Design of Everyday Things,” and co-founder of the Nielsen Norman Group.

Alan Dix: Author of the bestselling book “Human-Computer Interaction” and Director of the Computational Foundry at Swansea University.

Mike Rohde: Experience and Interface Designer, author of the bestselling “The Sketchnote Handbook.”

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!