Ideation for Design - Preparing for the Design Race

- 855 shares

- 4 years ago

Ideation is a creative process where designers generate ideas in sessions (e.g., brainstorming, worst possible idea). It is the third stage in the Design Thinking process. Participants gather with open minds to produce as many ideas as they can to address a problem statement in a facilitated, judgment-free environment.

See how Ideation helps build solutions.

It's challenging to gain the perspective to find design solutions. To have productive ideation sessions, you'll need a dedicated environment for standing back to seek and see every angle. First, though, your team must define the right problem to address. Ideation, or "Ideate", is the third step in the Design Thinking process – after “Empathize” (gaining user insights from research/observation) and “Define” (finding links/patterns within those insights to create a meaningful and workable problem statement or point of view).

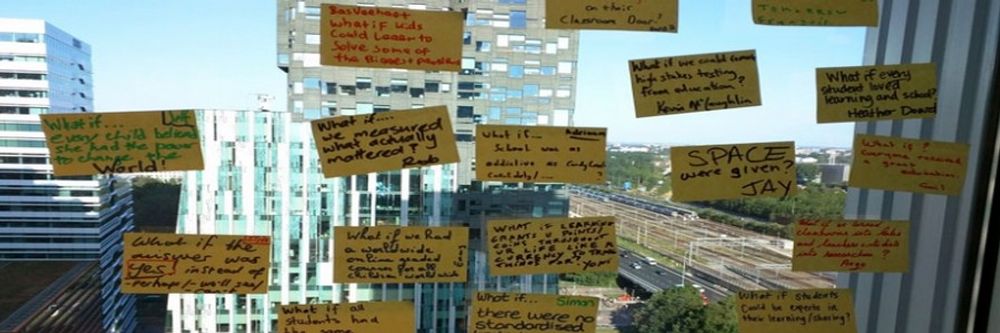

Before starting to look for ideas, your team needs a clearly defined problem to tackle – a focused problem statement or point of view (POV) to inspire and guide everyone. “How might we…?” questions—e.g., “How might we design an app finding cheap hotels in safe neighborhoods?”—help in reframing issues and prompting effective collaboration towards potential solutions. To bring people together to conjure ideas and bypass established frontiers, you need a skilled facilitator and a creative environment, including a prepared space, featuring posters of personas, relevant information, etc. Your team also requires rules – e.g., a 2-hour time limit, quantity-over-quality focus, ban on distractions such as phones, and “There are no bad ideas” mindset. By being bold and curious, participants can challenge commonly held beliefs and explore possibilities past these obstacles. Team members should take each other's ideas and build on them, find ways to link concepts, recognize patterns and flip seemingly impossible notions over to reveal new insights.

"It's not about coming up with the right idea, it's about generating the broadest range of possibilities.

- d.school, An Introduction to Design Thinking PROCESS GUIDE

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

There are hundreds of ideation techniques to help you in your ideation sessions. You want an ideation technique that combines your conscious and unconscious mind—fusing the rational with the creative. It must match the sorts of ideas your team must generate and reflect their nature, needs and experience with ideation. Some crucial ones are:

Brainstorming – You build good ideas from each other’s wild ideas.

Braindumping – This is like brainstorming, but done individually.

Brainwriting – This is like brainstorming, but everyone writes down and passes ideas for others to add to before discussing these.

Brainwalking – This is like brainwriting, but members walk about the room, adding to others’ ideas.

Worst Possible Idea – You take an inverted brainstorming approach, emboldening more reserved individuals to produce bad ideas and yielding valuable threads.

In this video, I'm going to give you an exercise to do. It's going to be an exercise in *bad ideas*. This is where I tip your brain towards madness. But hopefully – the boundary between creativity and genius and total madness is often said to be a thin one. So, by pushing you a little towards madness, I hope to also push you a little towards creativity,

and hopefully you can control the madness that comes there, but we'll see as it goes along. So, what I want you to do is – you know how hard it is to think of good ideas; everybody says, 'Ah, let's have a brainstorming session – have lots of ideas!'... So, if it's so hard to think of good ideas, why not think of a *bad idea*? So, what I'd like you to do as an exercise is just to think of a bad idea,

or a silly idea, a completely crazy idea. Now, it might be about something that you're doing at the moment. It might be a particular problem you've got. And so, what would be a really *bad idea* for sending notifications to people about something you want to get an engagement? Perhaps you could send them an email every three seconds or something like that. So, it could be that kind of bad idea, or it could be just an idea from the world.

So, and it could be a Heath Robinson sort of bad idea – something complex and arcane and that. Or perhaps – and this is probably a good one to start with – just an oxymoron. So, something like a chocolate teapot. So, something that *appears* to be really crazy, really silly: a car without an engine, I remember once in a session we had this, that doesn't seem like a good idea. So, you've got your bad idea – maybe a chocolate teapot or maybe the car with no engine

or something like that. And what I want you to do now is I'm going to take you through some prompt questions. First of all, this was a bad idea, right? The reason you chose it was because it was a bad idea. So, what I want you to do is say to yourself, 'What is bad about this idea?' So, think of the car without an engine. What's bad about a car without an engine? Well, it doesn't have an engine; it's obvious, right?

So, you start off with that. Now, you might think a bit more. But then I want you to dig and say, 'Well, *why* is that a bad idea?' Well, it's not got an engine – it can't go anywhere. Then dig a bit back further. So, are there things that you can think of that are like that that have that property – so, for instance, the car without an engine can't go anywhere. Are there things that can't go anywhere that are actually a good idea? Well...

a garden shed – a garden shed doesn't go anywhere, but that's not a bad idea. And, in fact, there are things you might not – you might want to have something that can't be stolen. You don't want that to go anywhere, so that's not a bad idea. So, if you can think of things that appear to share the bad thing but actually aren't bad, what's the difference? Why is not having an engine, why is not being able to go anywhere bad for the car but not bad for the garden shed?

And as you dig into this, hopefully you start to understand better these things. You can also go the other way around. So, you *know* this is a bad idea, but maybe there's something good about it. It hasn't got an engine – it's not polluting. Wow! We've got a green car! It will be green because all the moss will grow on it because it doesn't drive anywhere, but – you know – this is good, surely.

So, then you can think to yourself, 'Well, okay, if this is a good thing,' you can do the same sort of thing: 'Why is that a good thing?' Well, it doesn't choke you with its pollution. If you're finding this difficult, and particularly this is true about the bad idea bit, you want to... with the bad idea, you want to change that bad thing into a good thing, and so this is whether you want to find a good thing in the bad idea or you want to find a good use for the thing you've identified that's bad. You might try a *different context*. So, if you take the car off the road and put it perhaps into something where it's

moved along by something, perhaps sitting on the back of a lorry; why, you might want that. Well... you might want it so you can easily move your car. You might put it on something that's dragged along. So, you sometimes change the context and suddenly something that seemed bad suddenly is not so bad. So, the final thing you could do with your bad idea is *turn it into a good idea*.

Now, you might have already done this as part of that process. So, what's good? When you've identified something that's good about it – like the car, that it wasn't polluting – try to hold on to that, try to keep that and retain that good feature. But where you found the things – and you really dug down to *why something's bad*, not just the superficial – you know – 'it doesn't have an engine'; well, that's not bad in itself,

but the fact that means you can't drive anywhere – okay, that's bad. So, can you change that badness but still retain the non-pollutingness? So, perhaps we're going to have a truly green car. Perhaps we're going to have roads with sort of little wires you connect into and – you know – a bit like Scalextric cars and can drag the cars along so they don't have an engine and they're being powered elsewhere. You may, as I said, change the context entirely. So,

instead of it being a car for driving around in, instead just – I've already mentioned this one – stick your chickens in it and suddenly it becomes a hen coop. And I think if you go around the world, you'll find a lot of old cars, usually actually with their engine still sitting in them, that are being used as hen coops. If you had a *complex idea* – and this is true it could be for a simple idea – but in doing your thinking, there might be just something about it, something small;

it wasn't necessarily the whole thing. So, actually... the idea of the gap in the engine, perhaps you decided that would be really good, actually having the engine not there because you could put things in the front, and for whatever reason you think it's easier to put things in the front than the back. So, perhaps that becomes your idea, that actually you'd quite like to be able to put your luggage in the front of the car; you'd like more room in the car for luggage. And then perhaps you'll put an engine back in the car, but thinking about how you actually

improve access for luggage. If you've had one of those Heath Robinson complex ideas, Wallace and Gromit-like ideas, then actually you may not be trying to make the whole thing into a good idea. But within it, some little bit of that complex mechanism might be something that you've thought about, you've realized and suddenly think 'Ah!' and do something just with that. And I'll leave you with a glass hammer.

Challenging Assumptions – You overturn established beliefs about problems, revealing fresh perspectives.

Mindmapping – You use this graphical technique to connect ideas to problems’ major and minor qualities.

Sketching/Sketchstorming – You use rough sketches/diagrams to express ideas/potential solutions and explore the design space.

Storyboarding – You develop a visual problem/design/solution-related story to illustrate a situation’s dynamics.

SCAMPER – You question problems through action verbs (“Substitute”, “Combine”, “Adapt”, “Modify”, “Put to another use”, “Eliminate”, “Reverse”) to produce solutions.

Bodystorming – You use role-playing in scenarios/customer-journey steps to find solutions.

Analogies – You draw comparisons to communicate ideas better.

Provocation – You use an extreme lateral-thinking technique to challenge established beliefs and explore paths beyond.

Movement – You take a “what if?” approach to overcoming obstacles in ideation and finding themes/trends/attributes towards reliable solutions.

Cheatstorm – You use previously ideated material as stimuli.

Crowdstorming – Your target audiences generate and validate ideas through feedback (e.g., social media) to provide valuable solution insights.

Creative Pause – You take time to pull back from obstacles.

Other methods for ideation include co-creation workshops (combining user empathy research, ideation and prototyping), gamestorming (gamification-oriented ideation methods) and prototyping. The beauty of ideation is its unbounded freedom, although structured environments are critical. If you get stuck, you have fallbacks: e.g., “breaking the law” (listing constraints to see if you can overcome them), “stealing” ideas (emulating applicable concepts from other industries), inverting the problem and laddering (moving problems between the abstract and the concrete).

We have a course on Design Thinking, featuring lots of hands-on tools for ideation.

Read some practical tips on effective Ideation.

The Nielsen Norman Group’s Aurora Harley examines Ideation challenges, benefits and more.

See Google’s take on approaching Ideation.

To run a practical ideation workshop, start by setting a clear objective for the session. Gather a diverse group of participants to bring varied perspectives. Kick off with warm-up exercises to stimulate creativity. Use brainstorming, mind mapping, or "How might we?" questions to generate ideas. Ensure a facilitator guides the session, keeping discussions on track. Encourage open communication, emphasizing that all ideas, even unconventional ones, are welcome. After idea generation, prioritize and filter ideas for further exploration. Conclude by assigning the next steps and responsibilities. For a deeper dive into ideation preparation and techniques, refer to the Interaction Design Foundation's article on ideation.

Ideation in psychology refers to the process of forming ideas or concepts. It's integral to human cognition, allowing individuals to generate, develop, and communicate abstract thoughts. In a clinical context, the term can also relate to "suicidal ideation," which means having thoughts or plans about self-harm or suicide. However, in a broader sense, ideation emphasizes the creative aspect of our cognitive processes, which is central to problem-solving, innovation, and day-to-day thinking.

Several effective ideation techniques help designers generate creative solutions. Among the most popular are:

Teasing Apart and Piecing Together: This method involves deconstructing ideas and reassembling them for fresh insights.

Three-way Comparisons: Comparing three items or concepts can uncover new perspectives.

Embrace Opposites: By examining opposing views, one can identify innovative solutions.

I'd like to tell you now about a technique that I use often – a very simple technique to enhance structures. I've already got some sort of dimensional, categorical way of describing a problem and to make it richer or to explore whether you can make it richer. We often have things which *appear* to be opposites.

So, in political life you might have left wing versus right wing. In personalities, you might have an introvert versus extrovert. And whenever I'm faced with a dichotomy that says 'this or this', I ask myself, 'Can it be both?' So, we might have – in a classic user interface kit, we've been using menus as examples – you might have menus versus radio buttons.

And they're completely different things – something is either a menu or it's a radio button. Neither both. But what about, could you have something that's *both* a menu and a radio button? So, could you have something that looks like a menu, perhaps pulls down but has radio buttons inside it? Would that work? Or neither, of course, but neither is (inaud.) – you can think of things like text. But can it be both? So, rather than saying A or B – one or the other – can you actually have something that has elements of both going on?

And sometimes the answer is no and your categories are disjoint. But often if you ask about something being both, you learn something or at the very least you learn that these really are distinct. You can do the same for things that are – so that's true of things which are like menu versus radio button, which are categories, but also things like the left (inaudible) right button ring, which is more of a dimension. Sometimes you (inaud.) to ask if a thing is a bit of each. Can you have something that's *almost*

menu-like but also has a little bit of radio button? I'm not quite sure what that would be, but that might be true of, say, the fiction versus versus non-fiction. So, you might say, 'These are my fiction books. These are my non-fiction books.' You know – what would it mean for something to be mostly fiction with a little bit of non-fiction? So, again, a historical novel might fit into that category. And what you're doing then, actually, is you're taking what appears to be

*categorical distinction* – it's either this or this – and actually turning it into a *dimension*. It could be totally the one thing; it could be totally other – totally fiction, totally non-fiction, but possibly somewhere in between. So, you can both look at more rich categories, things that are both, but also *turn* what appears to be a categorical distinction into a dimensional one. And dimensions tend to be richer, partial things. They can be more problematic, but they're often richer. However, if you've got dimensions, you can do similar tricks to dimensions.

So, let's think of the classic personality trait – introvert, extrovert. And whenever I see a scale that's got something on one end, something on the other, I always want to twist it and say, 'Well, what about if it was bent in half? Can we imagine somebody who is both very introvert *and* very extrovert? Or can we imagine somebody who's very non-extrovert *and* very non-introvert? Do we have to see these as opposites? Can we actually think about combinations?

Maybe it's at different times; maybe it's at the same time. What would that mean? And we start to learn about the nature of personality, perhaps a richer way than if you see things always in terms of polarities. So, again, it's a powerful way. Again, sometimes the answer is you do something like this and you think, 'Actually, this is meaningless. There really, really is a distinction.' But so many times, I've found that what appears to be

the sort of middle neutral point in fact can consist of both – shall we say – a more neutral something that has neither characteristics, but also something that embodies both characteristics can be placed in that middle, and they're actually more that they sit out at the top right-hand corner. In one way, so what these opposites do is they again help you, as with many of the other techniques we've looked at, to feed your gut feelings.

So, some of the things we start off – when we start off with concrete examples, we've been taking something that's very solid. You know – I know this is a mug; I know this is a remote control, and dealing with those concrete things, and then using that to abstract, to start to have a vocabulary to talk about our problem domain. What we're doing here is taking that vocabulary and creating more of these gut feelings that enable us to actually look at it and think, 'Yes, I can imagine something there.'

Multiple Classifications: Categorizing ideas in various ways can lead to novel combinations.

More Specific and More General: Shifting focus between detailed and broad views can spark creativity.

We have moved back and forth between concrete examples and abstractions. And I'm going to talk a little bit more about that, particularly about the idea of being concrete, being very solid here. Often when we think of abstractions, that gives you a sense of being theoretical or academic, which, depending on where you come from, might be either a good or a bad thing; whereas when you think of design, we often think of more concrete fixed things,

artifact-driven processes where you build something, have a look at it. And these sometimes seem quite separate approaches; however, as with a lot of these things we've been discussing in creativity, the actual real fun and the real joy is when they come together. And we often get a greater power through actually doing a combination of the two. Pólya has a wonderful book *How To Solve It* – it was written quite a lot of years ago now – which is largely about mathematics problems, but is actually a really good book about problem solving

in general, although the examples are more about mathematics, and this is sort of high-school mathematics, the heuristics that are generated are very, very useful; so, it's very worth reading. In particular, some of the heuristics are very much about this area of how you move to be more abstract and more concrete. So, one of the heuristics is if you've got something you're trying to show or trying to solve, *think of something more specific*.

So, perhaps you're trying to design a generic web design tool that will work for any kind of shop. And you're struggling with that. So, then what you think is, 'Well, instead of designing it for any kind of shop, let's just imagine I'm designing it for pet shops or designing it for tool shops or food shops.' And then you go for some much more specific example; you sketch out what kind of site you'd want for a food shop,

the kinds of information you want about each product; work out how you might try and produce that, and then do it for some other examples, and then step back and look at the more general ones. You go more specific and then re-generalize. You might go the other direction. So, you might be trying to – perhaps you're actually working on a very specific shop design for a food shop and you're trying to think about how to lay out the different sections of the site and

– you know – perhaps you're going to have the fresh food section and you're going to have the tinned section and you're going to have the section where you put things like toilet rolls, whatever you call that section. And you're struggling with how to design this. Sometimes it might better stepping back and thinking, 'Well, actually this is about laying out lists or categories in general, and it's a bit like perhaps a library system.' And you think about more general examples, other examples of it. And by thinking more generally, sometimes it again gives you a kick

into the direction that might help you solve the more specific problem. A specific example of this is *adding constraints*. And we've talked about the way constraints, adding a constraint, which sounds like it makes life more difficult, sometimes frees your mind. This is true of process. So, for instance when you have a very time-constrained process, often you end up doing quite creative solutions because you 'can't do it properly'

because you haven't got the time, and so sometimes that works in the process, but also in the objects you're trying to construct. So, if you're trying to design something that's going to work on mobile devices in general, well, add a constraint to say, 'I'm actually only going to look at Android devices. I'm only going to look at phones of a very particular dimension. And then I will worry with that constraint.' Or I'm going to – perhaps it might be a constraint on the kinds of people involved: 'I'm going to assume that my users have

absolutely terrible memory. Can I create a website or a system or a form of interaction that works assuming my users have awful memory?' Hopefully, it'll work better when they do. You might design a different one. You might add a different constraint saying, 'Now I'm going to assume my users have perfect memory,' and you'll design something based on that. And then you'll look at those designs and see what you've learned from them; and then hopefully then, having added those constraints, remove them again and look at the general thing and say,

'Okay, given people a bit between these, what might I do in there?' Again, another example of this is where you've got numbers, is to try and make them either a lot bigger or a lot smaller. So, one of the examples I think I've used already is where you've got a website that you've been using a particular sort of format for and you suddenly discover that one of the menus gets so long it doesn't fit on the screen anymore.

And you think, 'Oh! What am I going to do?' and you might decide to perhaps make the font a little smaller, which of course works when you've got 12 items, but then of course the next time it gets bigger, there's a limit to how small you can make the font. So, one of the things you might do there is say, 'Okay, my struggle is that I've got 12 items and that's too many to fit on a standard screen.' What's a standard screen, of course? But let's go for that for a moment. What would happen if I had a *thousand* items in my menu? Well, now, clearly I can't just make the font smaller – it's not going to work.

I have to have a very different solution; so, I might go for a solution where the top level had perhaps – you know – things starting 'a' to 'b', things starting 'c' to 'd', that sort of alphabetic thing, a bit like going to library shelves. I might decide to classify things; so, instead of having 'a' to 'b's, it might be like the shop where you've got grocery items, paper items, whatever. But you're forced to think of very different solutions, and you might do one of

those solutions where it scrolls incredibly rapidly as you go off the bottom. But because you're thinking of a thousand items rather than 12, you're forced to expand your design space. Then you can go back to say, 'Well, actually it's never going to be anywhere near a thousand; it's probably going to always be... 10, 12, perhaps 20, but never huge.' However, your design space, the things you thought of, the solutions you've thought of are much wider,

and then you can look at those and say, 'Which ones actually now make sense when I've gone back to the sort of size that I was at?' In general, when we talk about being specific you might have already been thinking about prototyping. And so, we've talked about fairly concrete examples, how you might imagine these menus. Of course, you imagine something like that; there's a big difference between imagining it and actually seeing it in action. And that's why we like to build, as well as low-fidelity prototypes,

high-fidelity prototypes. That's partly so that you can show them to your users, you can show them to your clients, but it's also because when you look at that high-fidelity prototype, you react differently, you see things in it that you wouldn't see when things are a little bit more vague. Focusing on the physical side of that, there's wonderful stuff you get from actually being very physical. Now, some of that's about the fact that when you look at a physical design you learn

more about the nature of it: Does it fit into the hand well? How is the weight going to work? All sorts of things like that, but also actually the very nature of physicality – we are such visceral beings that actually we can use that as part of our design processes and our creativity processes. The very act of playing and doing exercise, just going out for a walk on its own, even if you're not even thinking about your design task, is itself

powerful in terms of the way it changes the chemical nature of a brain. So, actually just doing physical things can often be useful, even when it's sort of separate from what you're actually doing. However, also using it in your design process can be really powerful – creating mockups, and again remembering context, you might want to mock up the space around an interaction as well as the devices. So, again, if we're going to model this controller, you might want to model the controller. But you also might want to put it in the (inaudible) – if you haven't got the actual table

you can put it on, you might make a cardboard version of it and things like that. And I've actually seen in design studios people making whole living rooms out of corrugated cardboard in order to be able to have a sense of something working in its context. When you've got that mockup, of course you can act out what's going on. So, obviously if it's a very – if it's computationally high or intellectually high fidelity,

then you might actually be able to do the things and they have an effect. Otherwise, you might be just more a matter of acting through as if it was working, maybe using improvisational techniques – you might do that on your own, just going, almost like working to a script, or either as an individual or as a group of people together, to act through what might happen – you know. Somebody sitting down, using something; somebody walks into the room; maybe you're using a device as you're talking to somebody else,

and actually just doing a sort of improvisational session through that. So, this is from a lot of years ago. I was with a group of masters students, and we were talking about innovative interfaces. And I was asking them as a design exercise to think of a slightly future interaction. So, not something they could necessarily do now but that was about the way ubiquitous computing

– well, Internet of Things, actually the phrase didn't exist at that point, but that kind of computation was going. And, as an example, I just want to say – you know – the kind of thing that they might want to think of. I wanted to think of an example, so I scanned around my pockets and found my Swiss Army Knife. So, we started to talk about what an internet-enabled Swiss Army Knife might be like, and how you might have like a little screen on it. And I actually made my low-fi prototype here,

because I actually stuck a bit of cardboard on. But when we first did it, we just talked about it. And then I started to act it out, and I said, 'Ah. We're going use our toothpick as a stylus on our little tiny screen, so we can get suggestions up and it's going to say something like "Ah" – you know – "in order to fix your electric socket, what you do is you open this" – you know – maybe people have their own names, but I'm going to open a random one, a blade on it. Yeah, so you open your blade of a particular kind,

and they've probably got names for these blades, and then you read your instructions, and then you put it into the socket. And as I did this, I acted it out – I didn't actually put it in the socket; otherwise, I would have electrocuted myself, but I was acting it out. And as I went to move the knife to where I would perhaps undo the screw or something like that, I suddenly realized my thumb was over the virtual screen, the little – where we imagined the screen would be.

So, I was imagining this screen and when we talked abstractly, didn't notice. But as soon as acted out, it became absolutely obvious that your thumb blocked it. We could then think of alternatives; perhaps an audio interface with perhaps little Bluetooth earphones would probably make a lot more sense that talked you through it, rather than the little screen on it. But actually physically acting it out was what made the difference. Let's just summarize – being concrete, it has lots of things it does for you.

First of all, it *recruits your physical intelligence*, and in two senses. There's both your – where we think about physical things, we use a lot of knowledge and a lot of background knowledge we've been building up since we were, well, basically about that big. You know – so, even as a tiny baby you're reaching out to stuff, and we've built this huge physical understanding of the world, and when we make things concrete we use that. Now, even if it's not physical, even it's like a screen design that's very fixed, you've got a lot more ability

to look at something and think, 'Ah, that doesn't look like it works.' in a way that sometimes it can be hard to with something abstract. It *exposes details*; it pushes you to detail. Sometimes having too much detail gets in the way. But also that for other purposes, seeing those details actually kicks you to realize that's just never going to work. Now, then you can back off and go back into a more abstract discussion, so you move back and forth between the sort of very detailed and concrete and perhaps something that's more abstract;

that might be more abstract in a more discursive sense; it might be more abstract in a more sketch-like sense. I also find that *being concrete helps cut out waffle*. It's very easy to say something like, 'And we'll have a mobile version.' But then if you think, not 'What would it actually have in it?' but 'What might a mobile version look like?' So, this is not about saying 'let's design the mobile version' but to say,

'Can you at least have one example of how this kind of application would work?' And then you might discover very rapidly problems that arise, that if you just say, 'And we'll have the mobile version,' you just never notice. And the other thing is it's just *fun* – being more concrete, whether, again, it's really physically concrete, which is always a lot of fun, but actually this is true about things which look more real in general. I often find it's just fun!

Bad Ideas: Embracing seemingly poor ideas can sometimes pave the way to brilliant ones.

Enhance your ideation skills—dive deeper into these and several other methods in our courses on Design Thinking and Creativity.

In design thinking, ideation is a crucial phase of creative brainstorming. As highlighted in this video by Riley Hunt, the UX design process follows five main steps: Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test.

Specifically, during the Ideate phase, teams ensure everyone has a shared understanding of the problem at hand. A brainstorming session then follows, generating numerous solutions, even if some seem outlandish. After generating many ideas, teams evaluate these options, selecting the most viable and practical solutions to develop and prototype further. Ideation, therefore, serves as a bridge between understanding user needs and crafting tangible solutions.

Ideation is a broad term that encompasses various techniques and methods to generate, develop, and communicate new ideas. It's an integral part of the design thinking, helping teams explore solutions for complex problems. On the other hand, brainstorming is a specific, collaborative ideation technique where a group spontaneously contributes ideas without judgment. The goal of brainstorming is to produce a large quantity of ideas in a short time. In essence, while brainstorming is a popular form of ideation, ideation is the overarching process of generating ideas, encompassing many techniques beyond brainstorming. To understand more, explore our detailed article on brainstorming.

Ideation is the creative process of generating, developing, and communicating new ideas. Intent, conversely, is the underlying purpose or objective behind a specific action or design choice. Ideation involves brainstorming myriad solutions, while intent ensures the selected solution aligns with user needs and project goals. Semi-structured interviews can be invaluable for a deeper understanding of human behavior and decision-making. As this video highlights, these interviews help capture the "why" behind actions, revealing perceptions, values, and experiences.

However, they might not always charge the "what" or the tacit knowledge people take for granted. Therefore, complementing interviews with observation methods can offer a holistic view. Dive deeper into the ideation process in our comprehensive article, Ideation for Design.

Ideation and innovation are closely linked concepts central to the creative process. Ideation refers to the generation of new, novel ideas. It involves sparking diverse thoughts and navigating various forms of creativity, whether artistic, technical, or personal. On the other hand, innovation arises when you pair novel ideas (ideation) with their usefulness. More is needed for an argument to be unique; it must also effectively solve a problem or meet a need. Thus, while ideation emphasizes the birth of new ideas, innovation combines these ideas with practical utility to bring transformative solutions. Both concepts are essential for creative growth, but innovation requires a more comprehensive approach, fusing novelty with functionality.

For an in-depth exploration of ideation, check out the Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide course offered by Interaction-Design.org. This comprehensive course delves into the design thinking process, emphasizing ideation techniques. Enroll to uncover effective brainstorming methods, collaborative idea generation practices, and strategies to boost creativity. Suitable for both newcomers and experienced designers, this course provides the necessary tools to master ideation and its real-world applications. Enhance your ideation prowess today!

Here's the entire UX literature on Ideation by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Ideation with our course Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide .

Some of the world’s leading brands, such as Apple, Google, Samsung, and General Electric, have rapidly adopted the design thinking approach, and design thinking is being taught at leading universities around the world, including Stanford d.school, Harvard, and MIT. What is design thinking, and why is it so popular and effective?

Design Thinking is not exclusive to designers—all great innovators in literature, art, music, science, engineering and business have practiced it. So, why call it Design Thinking? Well, that’s because design work processes help us systematically extract, teach, learn and apply human-centered techniques to solve problems in a creative and innovative way—in our designs, businesses, countries and lives. And that’s what makes it so special.

The overall goal of this design thinking course is to help you design better products, services, processes, strategies, spaces, architecture, and experiences. Design thinking helps you and your team develop practical and innovative solutions for your problems. It is a human-focused, prototype-driven, innovative design process. Through this course, you will develop a solid understanding of the fundamental phases and methods in design thinking, and you will learn how to implement your newfound knowledge in your professional work life. We will give you lots of examples; we will go into case studies, videos, and other useful material, all of which will help you dive further into design thinking. In fact, this course also includes exclusive video content that we've produced in partnership with design leaders like Alan Dix, William Hudson and Frank Spillers!

This course contains a series of practical exercises that build on one another to create a complete design thinking project. The exercises are optional, but you’ll get invaluable hands-on experience with the methods you encounter in this course if you complete them, because they will teach you to take your first steps as a design thinking practitioner. What’s equally important is you can use your work as a case study for your portfolio to showcase your abilities to future employers! A portfolio is essential if you want to step into or move ahead in a career in the world of human-centered design.

Design thinking methods and strategies belong at every level of the design process. However, design thinking is not an exclusive property of designers—all great innovators in literature, art, music, science, engineering, and business have practiced it. What’s special about design thinking is that designers and designers’ work processes can help us systematically extract, teach, learn, and apply these human-centered techniques in solving problems in a creative and innovative way—in our designs, in our businesses, in our countries, and in our lives.

That means that design thinking is not only for designers but also for creative employees, freelancers, and business leaders. It’s for anyone who seeks to infuse an approach to innovation that is powerful, effective and broadly accessible, one that can be integrated into every level of an organization, product, or service so as to drive new alternatives for businesses and society.

You earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you complete the course. You can highlight them on your resume, CV, LinkedIn profile or your website.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!