Ideation for Design - Preparing for the Design Race

- 853 shares

- 4 years ago

Ideation is a creative process where designers generate ideas in sessions (e.g., brainstorming, worst possible idea). It is the third stage in the Design Thinking process. Participants gather with open minds to produce as many ideas as they can to address a problem statement in a facilitated, judgment-free environment.

See how Ideation helps build solutions.

It's challenging to gain the perspective to find design solutions. To have productive ideation sessions, you'll need a dedicated environment for standing back to seek and see every angle. First, though, your team must define the right problem to address. Ideation, or "Ideate", is the third step in the Design Thinking process – after “Empathize” (gaining user insights from research/observation) and “Define” (finding links/patterns within those insights to create a meaningful and workable problem statement or point of view).

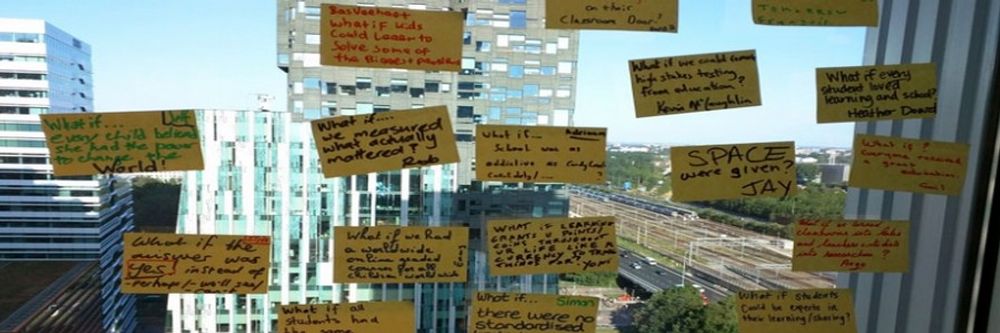

Before starting to look for ideas, your team needs a clearly defined problem to tackle – a focused problem statement or point of view (POV) to inspire and guide everyone. “How might we…?” questions—e.g., “How might we design an app finding cheap hotels in safe neighborhoods?”—help in reframing issues and prompting effective collaboration towards potential solutions. To bring people together to conjure ideas and bypass established frontiers, you need a skilled facilitator and a creative environment, including a prepared space, featuring posters of personas, relevant information, etc. Your team also requires rules – e.g., a 2-hour time limit, quantity-over-quality focus, ban on distractions such as phones, and “There are no bad ideas” mindset. By being bold and curious, participants can challenge commonly held beliefs and explore possibilities past these obstacles. Team members should take each other's ideas and build on them, find ways to link concepts, recognize patterns and flip seemingly impossible notions over to reveal new insights.

"It's not about coming up with the right idea, it's about generating the broadest range of possibilities.

- d.school, An Introduction to Design Thinking PROCESS GUIDE

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

There are hundreds of ideation techniques to help you in your ideation sessions. You want an ideation technique that combines your conscious and unconscious mind—fusing the rational with the creative. It must match the sorts of ideas your team must generate and reflect their nature, needs and experience with ideation. Some crucial ones are:

Brainstorming – You build good ideas from each other’s wild ideas.

Braindumping – This is like brainstorming, but done individually.

Brainwriting – This is like brainstorming, but everyone writes down and passes ideas for others to add to before discussing these.

Brainwalking – This is like brainwriting, but members walk about the room, adding to others’ ideas.

Worst Possible Idea – You take an inverted brainstorming approach, emboldening more reserved individuals to produce bad ideas and yielding valuable threads.

Challenging Assumptions – You overturn established beliefs about problems, revealing fresh perspectives.

Mindmapping – You use this graphical technique to connect ideas to problems’ major and minor qualities.

Sketching/Sketchstorming – You use rough sketches/diagrams to express ideas/potential solutions and explore the design space.

Storyboarding – You develop a visual problem/design/solution-related story to illustrate a situation’s dynamics.

SCAMPER – You question problems through action verbs (“Substitute”, “Combine”, “Adapt”, “Modify”, “Put to another use”, “Eliminate”, “Reverse”) to produce solutions.

Bodystorming – You use role-playing in scenarios/customer-journey steps to find solutions.

Analogies – You draw comparisons to communicate ideas better.

Provocation – You use an extreme lateral-thinking technique to challenge established beliefs and explore paths beyond.

Movement – You take a “what if?” approach to overcoming obstacles in ideation and finding themes/trends/attributes towards reliable solutions.

Cheatstorm – You use previously ideated material as stimuli.

Crowdstorming – Your target audiences generate and validate ideas through feedback (e.g., social media) to provide valuable solution insights.

Creative Pause – You take time to pull back from obstacles.

Other methods for ideation include co-creation workshops (combining user empathy research, ideation and prototyping), gamestorming (gamification-oriented ideation methods) and prototyping. The beauty of ideation is its unbounded freedom, although structured environments are critical. If you get stuck, you have fallbacks: e.g., “breaking the law” (listing constraints to see if you can overcome them), “stealing” ideas (emulating applicable concepts from other industries), inverting the problem and laddering (moving problems between the abstract and the concrete).

We have a course on Design Thinking, featuring lots of hands-on tools for ideation.

Read some practical tips on effective Ideation.

The Nielsen Norman Group’s Aurora Harley examines Ideation challenges, benefits and more.

See Google’s take on approaching Ideation.

To run a practical ideation workshop, start by setting a clear objective for the session. Gather a diverse group of participants to bring varied perspectives. Kick off with warm-up exercises to stimulate creativity. Use brainstorming, mind mapping, or "How might we?" questions to generate ideas. Ensure a facilitator guides the session, keeping discussions on track. Encourage open communication, emphasizing that all ideas, even unconventional ones, are welcome. After idea generation, prioritize and filter ideas for further exploration. Conclude by assigning the next steps and responsibilities. For a deeper dive into ideation preparation and techniques, refer to the Interaction Design Foundation's article on ideation.

Ideation in psychology refers to the process of forming ideas or concepts. It's integral to human cognition, allowing individuals to generate, develop, and communicate abstract thoughts. In a clinical context, the term can also relate to "suicidal ideation," which means having thoughts or plans about self-harm or suicide. However, in a broader sense, ideation emphasizes the creative aspect of our cognitive processes, which is central to problem-solving, innovation, and day-to-day thinking.

Several effective ideation techniques help designers generate creative solutions. Among the most popular are:

Teasing Apart and Piecing Together: This method involves deconstructing ideas and reassembling them for fresh insights.

Three-way Comparisons: Comparing three items or concepts can uncover new perspectives.

We'd like to make tacit things, things we know, *explicit*. One of the ways to do that is through making comparisons, to look at the distinctions between things. So, let's look at simple comparisons. The simplest one is just to look at two things. It might be two documents; it might be two systems; it might be two solutions to the same problem – perhaps two different kinds of menu in the system we're looking at.

So, you look at them and then you just ask simple questions: What's the same? What's different between them? And it's the difference which is often the interesting things. It's easy to – when you say they're the same – you know – these are both fruit; that doesn't tell you that much. But what's so different between an apple and an orange? What's so different between the kind of menu you get on a phone as opposed to the kind of menu you get on a web page? And by talking about those distinctions and those differences, you start to *make sense and understand things about them*. So, sometimes that can happen on simple two-way comparisons.

Sometimes, a *three-way comparison* can be a bit more helpful. So, when you have two things to compare, sometimes it's easy to fall back into standard differences. So, again, with my apple and orange, I might just say, 'Well, this is a citrus fruit and this isn't.' or something like that. So, I have a set of standard categories. This is sort of top-down reasoning, going from book knowledge, rather than from sort of bottom-up reasoning. Three-way comparisons can help here sometimes to actually say, 'In what way is this like this but different from something else?'

And sometimes you can deliberately play with this, try different orders so the obvious answer is taken away from you. The origins of this are in repertory grid techniques which are used for personality tests. And they're used to ask people three-way comparisons as a way of sort of finding out about the way their personality is. However, you can use it for all sorts of kinds of technique. You can use it yourself to look at techniques and ask yourself this question,

or you can use it with your users. So, here's an example we'll go back to the apples and orange. So, I've brought my fruit bowl, if it can't fall out. And in my fruit bowl I've got some grapes, I've got an orange, I've got an apple. What you might do is say, 'Okay, I've got an apple and orange. How are an apple and orange similar to one another but different from grapes?' And you could probably already start to think of answers yourselves. We have different answers because this is about exposing our tacit distinctions.

So, you might apply this – if you're working with fruit manufacturers, you might ask this question, but obviously for user experience, this might be two different, three different menu systems. And so, for these apples and oranges I might think about something like *size*. So, these are bigger than – well, certainly than an individual grape, not necessarily than the whole bunch, but an apple and orange are bigger than single grapes. You might use size as a distinction. But you notice it's interesting even there, I've started to have to talk about some

subtlety in here, which is often the case. Do you eat one or many? So, typically when you have an apple or orange, you just have one apple or one orange, but when you have grapes, you usually don't have just one grape – you usually have several, partly because they're smaller. But actually, because they're smaller, we're already seeing interesting relationships. Obviously, if you have something small, you eat more of them. I've said they're not in wine – okay, you know, you make wine out of grapes. That's an odd one because I could say that – you know – apples you can make cider with, all sorts of things.

But obviously, I think grapes are so closely associated with wine in my head, that seems sensible for me given my distinction. So, this is obviously exposing not just what these differences are, but actually about the *way that I see the world* – the categories I impose on the world. So, we expose the categories that we have there by making these distinctions. And so, one of the interesting things is when you have – if you just do it one way round, obviously you can again sometimes drop into standard links,

and perhaps in my head I put apples and oranges closer to themselves than I do to grapes. But I can break that by deliberately mixing things up. So, now I can say, 'Okay, given an orange and a grape or oranges and grapes, how are they more similar to one another than they are to apples? How is an apple different from them?' So, now I can't use the set of distinctions I had before, so I'm forced to think of new ways. So, again, if I was doing my menus and buttons and web links,

I'm going to start thinking, 'How is' – I can't remember, I have to put labels on these, but – you know – 'How is my web link different from my buttons and menus?' But then having done that, I shuffle them around and I can't use the same distinctions. I've got to think of new differences. Being in Britain, I think about things that I associate more with being things that are grown in Britain. I still think of apples as a typical British fruit. Now, it's interesting – so, before I was thinking about the eating qualities of these,

when I was doing another comparison. Now, I've been forced to think about where they're grown, and also that this was not a hard distinction; notice – you know – this was more easily grown. And probably it's more like I've created a dimension where apples are at one end and oranges another and grapes sitting in the middle. I've sort of – so, having said that I eat one of the other fruits, I've sort of put these into another similar category, saying, 'Well, actually, when I open the orange, there's multiple

segments, just like there's multiple fruits here; whereas the apple is an apple.' – you know. If you cut it up, the core inside is segmented but the actual flesh is continuous. So, that's another distinction. And then, of course, you force yourself again. You say, 'Okay. Okay, I've done the other comparisons. What about putting apples with grapes and oranges on their own?' And, again, I found a different set of distinctions there. For some reason, when you go to visit somebody in hospital, you tend to think of bringing apples or grapes, but not so much oranges – even though an orange has got lots of vitamin C in it.

I think part of the reason is about *messiness*. You know – these are good lunchbox foods. You know – you can eat your apple; you can pull off your peel. It's harder, unless you get those easy-peel oranges, to have an orange in your lunchbox because when you cut it, it spurts everywhere. And – oh yeah – that was another thought, what I thought was these two I eat the skin of. You can eat the skin of an orange, but most people don't. So, you notice what we've done here is we've *pulled out a whole different set of distinctions*.

We've got things about the nature of the flesh in the fruits; we've got the nature of the skins; we've got the size of them; we've got where they're grown. It's a whole lot of different things we're understanding about fruit by doing these sets of comparisons with these three fruit. Typically, the closer the things are you're trying to do these comparisons – that's whether you're doing a two-way comparison or a three-way comparison like this –

the *closer* things are to one another, the *more interesting you get the results* because you're forced to make finer and finer distinctions and that exposes more interesting things about the domain. So, comparing buttons and menus, if you're not careful, you'll fall again into standard categories. Comparing two relatively similar menu systems with each other, you probably start to get some more interesting distinctions out that help you learn about your domain. So, yes, I was giving an example here – oranges and apples;

maybe you learn more about fruit than if you compare an orange with a car, because an orange is a fruit, a car isn't. So, the closer they are, the harder it is to fall into standard distinctions. Having said that, maybe you'll find some interesting things if you look at an apple and say, 'Is an apple more like a tractor or a train?' And this is, I guess, close to sort of bad ideas thinking. Or – you know – sometimes you're asked perhaps, 'What fruit are you like?'

You know – if you go around the people you know in the office, if you were going to give each person a fruit that represented them, which would it be? And then ask yourself *why*. So, if I'm going to say an apple is more like a tractor, is that because tractors are more agricultural? Or maybe I think it's more like a train because perhaps as a child if I went on train trips, I always had an apple to eat while we were on the train. So, by making these, again, closer is often better, but sometimes you make those wild comparisons – you also end up with some interesting things.

Embrace Opposites: By examining opposing views, one can identify innovative solutions.

Multiple Classifications: Categorizing ideas in various ways can lead to novel combinations.

More Specific and More General: Shifting focus between detailed and broad views can spark creativity.

Bad Ideas: Embracing seemingly poor ideas can sometimes pave the way to brilliant ones.

In this video, I'm going to give you an exercise to do. It's going to be an exercise in *bad ideas*. This is where I tip your brain towards madness. But hopefully – the boundary between creativity and genius and total madness is often said to be a thin one. So, by pushing you a little towards madness, I hope to also push you a little towards creativity,

and hopefully you can control the madness that comes there, but we'll see as it goes along. So, what I want you to do is – you know how hard it is to think of good ideas; everybody says, 'Ah, let's have a brainstorming session – have lots of ideas!'... So, if it's so hard to think of good ideas, why not think of a *bad idea*? So, what I'd like you to do as an exercise is just to think of a bad idea,

or a silly idea, a completely crazy idea. Now, it might be about something that you're doing at the moment. It might be a particular problem you've got. And so, what would be a really *bad idea* for sending notifications to people about something you want to get an engagement? Perhaps you could send them an email every three seconds or something like that. So, it could be that kind of bad idea, or it could be just an idea from the world.

So, and it could be a Heath Robinson sort of bad idea – something complex and arcane and that. Or perhaps – and this is probably a good one to start with – just an oxymoron. So, something like a chocolate teapot. So, something that *appears* to be really crazy, really silly: a car without an engine, I remember once in a session we had this, that doesn't seem like a good idea. So, you've got your bad idea – maybe a chocolate teapot or maybe the car with no engine

or something like that. And what I want you to do now is I'm going to take you through some prompt questions. First of all, this was a bad idea, right? The reason you chose it was because it was a bad idea. So, what I want you to do is say to yourself, 'What is bad about this idea?' So, think of the car without an engine. What's bad about a car without an engine? Well, it doesn't have an engine; it's obvious, right?

So, you start off with that. Now, you might think a bit more. But then I want you to dig and say, 'Well, *why* is that a bad idea?' Well, it's not got an engine – it can't go anywhere. Then dig a bit back further. So, are there things that you can think of that are like that that have that property – so, for instance, the car without an engine can't go anywhere. Are there things that can't go anywhere that are actually a good idea? Well...

a garden shed – a garden shed doesn't go anywhere, but that's not a bad idea. And, in fact, there are things you might not – you might want to have something that can't be stolen. You don't want that to go anywhere, so that's not a bad idea. So, if you can think of things that appear to share the bad thing but actually aren't bad, what's the difference? Why is not having an engine, why is not being able to go anywhere bad for the car but not bad for the garden shed?

And as you dig into this, hopefully you start to understand better these things. You can also go the other way around. So, you *know* this is a bad idea, but maybe there's something good about it. It hasn't got an engine – it's not polluting. Wow! We've got a green car! It will be green because all the moss will grow on it because it doesn't drive anywhere, but – you know – this is good, surely.

So, then you can think to yourself, 'Well, okay, if this is a good thing,' you can do the same sort of thing: 'Why is that a good thing?' Well, it doesn't choke you with its pollution. If you're finding this difficult, and particularly this is true about the bad idea bit, you want to... with the bad idea, you want to change that bad thing into a good thing, and so this is whether you want to find a good thing in the bad idea or you want to find a good use for the thing you've identified that's bad. You might try a *different context*. So, if you take the car off the road and put it perhaps into something where it's

moved along by something, perhaps sitting on the back of a lorry; why, you might want that. Well... you might want it so you can easily move your car. You might put it on something that's dragged along. So, you sometimes change the context and suddenly something that seemed bad suddenly is not so bad. So, the final thing you could do with your bad idea is *turn it into a good idea*.

Now, you might have already done this as part of that process. So, what's good? When you've identified something that's good about it – like the car, that it wasn't polluting – try to hold on to that, try to keep that and retain that good feature. But where you found the things – and you really dug down to *why something's bad*, not just the superficial – you know – 'it doesn't have an engine'; well, that's not bad in itself,

but the fact that means you can't drive anywhere – okay, that's bad. So, can you change that badness but still retain the non-pollutingness? So, perhaps we're going to have a truly green car. Perhaps we're going to have roads with sort of little wires you connect into and – you know – a bit like Scalextric cars and can drag the cars along so they don't have an engine and they're being powered elsewhere. You may, as I said, change the context entirely. So,

instead of it being a car for driving around in, instead just – I've already mentioned this one – stick your chickens in it and suddenly it becomes a hen coop. And I think if you go around the world, you'll find a lot of old cars, usually actually with their engine still sitting in them, that are being used as hen coops. If you had a *complex idea* – and this is true it could be for a simple idea – but in doing your thinking, there might be just something about it, something small;

it wasn't necessarily the whole thing. So, actually... the idea of the gap in the engine, perhaps you decided that would be really good, actually having the engine not there because you could put things in the front, and for whatever reason you think it's easier to put things in the front than the back. So, perhaps that becomes your idea, that actually you'd quite like to be able to put your luggage in the front of the car; you'd like more room in the car for luggage. And then perhaps you'll put an engine back in the car, but thinking about how you actually

improve access for luggage. If you've had one of those Heath Robinson complex ideas, Wallace and Gromit-like ideas, then actually you may not be trying to make the whole thing into a good idea. But within it, some little bit of that complex mechanism might be something that you've thought about, you've realized and suddenly think 'Ah!' and do something just with that. And I'll leave you with a glass hammer.

Enhance your ideation skills—dive deeper into these and several other methods in our courses on Design Thinking and Creativity.

In design thinking, ideation is a crucial phase of creative brainstorming. As highlighted in this video by Riley Hunt, the UX design process follows five main steps: Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test.

Specifically, during the Ideate phase, teams ensure everyone has a shared understanding of the problem at hand. A brainstorming session then follows, generating numerous solutions, even if some seem outlandish. After generating many ideas, teams evaluate these options, selecting the most viable and practical solutions to develop and prototype further. Ideation, therefore, serves as a bridge between understanding user needs and crafting tangible solutions.

Ideation is a broad term that encompasses various techniques and methods to generate, develop, and communicate new ideas. It's an integral part of the design thinking, helping teams explore solutions for complex problems. On the other hand, brainstorming is a specific, collaborative ideation technique where a group spontaneously contributes ideas without judgment. The goal of brainstorming is to produce a large quantity of ideas in a short time. In essence, while brainstorming is a popular form of ideation, ideation is the overarching process of generating ideas, encompassing many techniques beyond brainstorming. To understand more, explore our detailed article on brainstorming.

Ideation is the creative process of generating, developing, and communicating new ideas. Intent, conversely, is the underlying purpose or objective behind a specific action or design choice. Ideation involves brainstorming myriad solutions, while intent ensures the selected solution aligns with user needs and project goals. Semi-structured interviews can be invaluable for a deeper understanding of human behavior and decision-making. As this video highlights, these interviews help capture the "why" behind actions, revealing perceptions, values, and experiences.

However, they might not always charge the "what" or the tacit knowledge people take for granted. Therefore, complementing interviews with observation methods can offer a holistic view. Dive deeper into the ideation process in our comprehensive article, Ideation for Design.

Ideation and innovation are closely linked concepts central to the creative process. Ideation refers to the generation of new, novel ideas. It involves sparking diverse thoughts and navigating various forms of creativity, whether artistic, technical, or personal. On the other hand, innovation arises when you pair novel ideas (ideation) with their usefulness. More is needed for an argument to be unique; it must also effectively solve a problem or meet a need. Thus, while ideation emphasizes the birth of new ideas, innovation combines these ideas with practical utility to bring transformative solutions. Both concepts are essential for creative growth, but innovation requires a more comprehensive approach, fusing novelty with functionality.

For an in-depth exploration of ideation, check out the Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide course offered by Interaction-Design.org. This comprehensive course delves into the design thinking process, emphasizing ideation techniques. Enroll to uncover effective brainstorming methods, collaborative idea generation practices, and strategies to boost creativity. Suitable for both newcomers and experienced designers, this course provides the necessary tools to master ideation and its real-world applications. Enhance your ideation prowess today!

Here's the entire UX literature on Ideation by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Take a deep dive into Ideation with our course Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide .

Some of the world’s leading brands, such as Apple, Google, Samsung, and General Electric, have rapidly adopted the design thinking approach, and design thinking is being taught at leading universities around the world, including Stanford d.school, Harvard, and MIT. What is design thinking, and why is it so popular and effective?

Design Thinking is not exclusive to designers—all great innovators in literature, art, music, science, engineering and business have practiced it. So, why call it Design Thinking? Well, that’s because design work processes help us systematically extract, teach, learn and apply human-centered techniques to solve problems in a creative and innovative way—in our designs, businesses, countries and lives. And that’s what makes it so special.

The overall goal of this design thinking course is to help you design better products, services, processes, strategies, spaces, architecture, and experiences. Design thinking helps you and your team develop practical and innovative solutions for your problems. It is a human-focused, prototype-driven, innovative design process. Through this course, you will develop a solid understanding of the fundamental phases and methods in design thinking, and you will learn how to implement your newfound knowledge in your professional work life. We will give you lots of examples; we will go into case studies, videos, and other useful material, all of which will help you dive further into design thinking. In fact, this course also includes exclusive video content that we've produced in partnership with design leaders like Alan Dix, William Hudson and Frank Spillers!

This course contains a series of practical exercises that build on one another to create a complete design thinking project. The exercises are optional, but you’ll get invaluable hands-on experience with the methods you encounter in this course if you complete them, because they will teach you to take your first steps as a design thinking practitioner. What’s equally important is you can use your work as a case study for your portfolio to showcase your abilities to future employers! A portfolio is essential if you want to step into or move ahead in a career in the world of human-centered design.

Design thinking methods and strategies belong at every level of the design process. However, design thinking is not an exclusive property of designers—all great innovators in literature, art, music, science, engineering, and business have practiced it. What’s special about design thinking is that designers and designers’ work processes can help us systematically extract, teach, learn, and apply these human-centered techniques in solving problems in a creative and innovative way—in our designs, in our businesses, in our countries, and in our lives.

That means that design thinking is not only for designers but also for creative employees, freelancers, and business leaders. It’s for anyone who seeks to infuse an approach to innovation that is powerful, effective and broadly accessible, one that can be integrated into every level of an organization, product, or service so as to drive new alternatives for businesses and society.

You earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you complete the course. You can highlight them on your resume, CV, LinkedIn profile or your website.

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge. Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change, , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge!